By Di Freeze

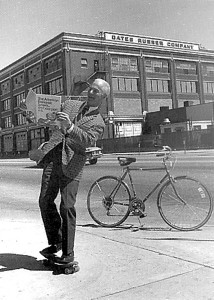

Charles C. Gates Jr. has been involved in “everything from belts to batteries to barnyard boots” and “eggs to aircraft.” Named in the 2001 list of “Forbes 400 Richest Americans,’ he’ll never get away from one title.

“Yes, I’m the ‘Rubber Man,'” he confirms with a grin. Known as “Charlie” to his friends, he adds that he’s also known as the “Belt Flipper.” He explains that when you’re making belts—and The Gates Rubber Company has made plenty of those—you make the “interior and the guts” and then you “flip it,” to add the skin.

An alluring blend of old-world charm and good-ole-boy humor, Gates has escaped the play on words associated with his last name, which brother Harry didn’t escape.

“He was referred to as ‘Pearly Gates.’ That was a nickname from school. He was far from that,” he says with a laugh.

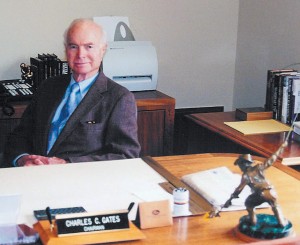

By the time The Gates Rubber Company merged with Tomkins PLC of London, in July 1996, the unit had sales of over $1 billion. By that year, The Gates Corporation, privately held, of which Charles C. Gates Jr. served as chairman and chief executive officer, employed over 14,000 people, serving customers from a total of 170 locations worldwide, including 40 manufacturing facilities in 13 countries. The corporation’s major business units were The Gates Rubber Company, Gates Formed-Fibre Products, Inc., Gates Power Drive Products, Inc., Cody Energy, Inc., A Bar A, Inc., and the Gates Land Company.

In his office, surrounded by mementos of the family legacy, as well as his association with aviation (Gates Learjet and the Combs Gates network of fixed base operations, in particular) and various organizations, he talks about his origin.

“I was born in motion,” he says, smiling. He could be referring to constant activity, or his actual birth.

It’s a Boy!

Charles Cassius and Hazel (Rhoads) Gates were the proud parents of four daughters—Ruth, Hazel, LeBurta, and Charla. On May 27, 1921, as they made their way down Bear Creek Canyon towards a hospital in Denver, they were hoping that the baby she was now carrying was a boy—and would wait just a little longer before entering the world.

“You might say I hit the ground on rubber—going about 60 miles an hour,” Gates says.

Actually, after pulling the family roadster over, Charles Gates delivered the baby, in the backseat. Then, the Gates turned around, found a doctor—at about 2:00 a.m.—and returned home. Luckily, says Charles Gates Jr., his mother was “quite experienced in child bearing.”

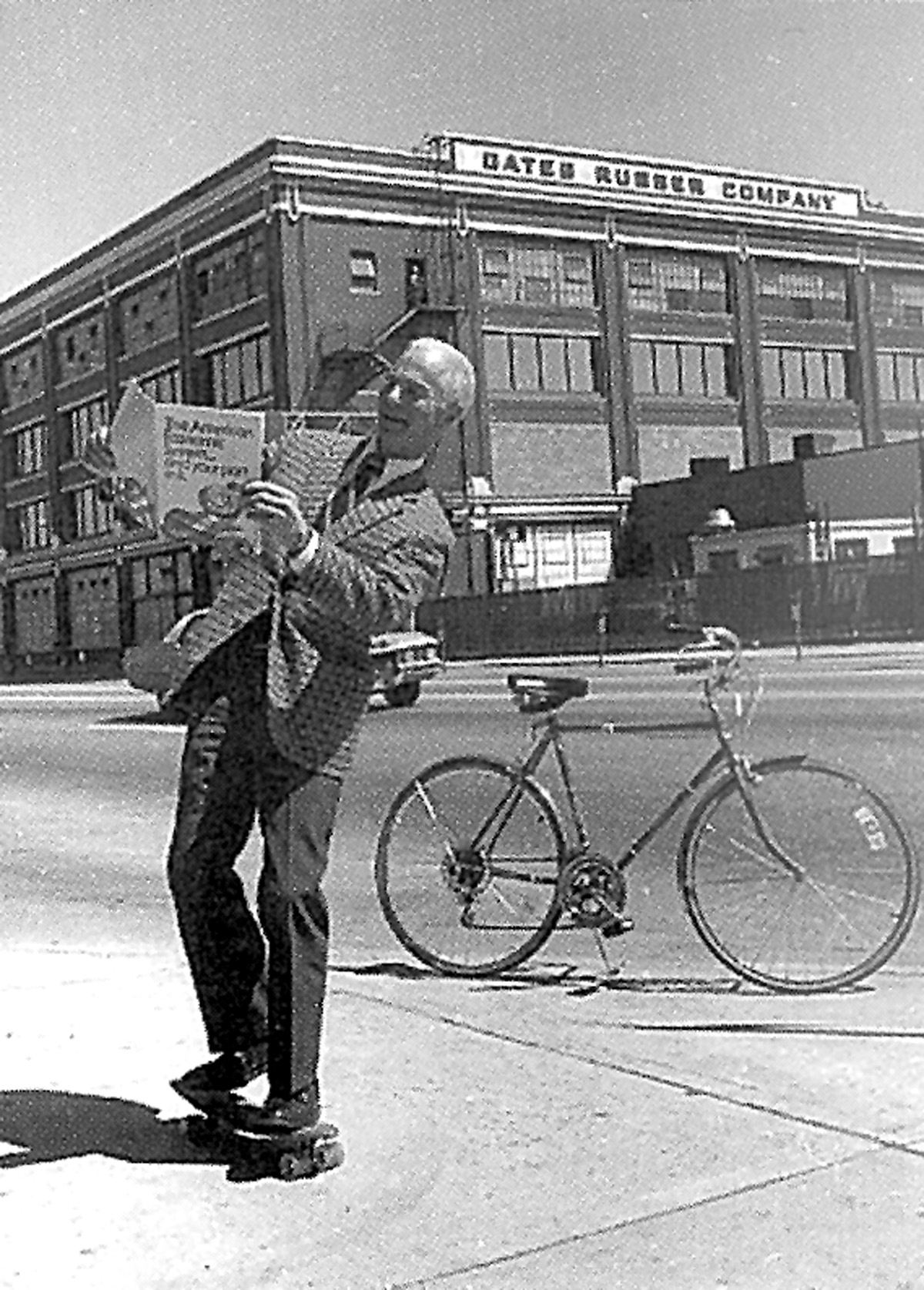

Hours later, Charles Gates Sr. arrived at the Gates Rubber Company, where employees gleefully placed pillows on the street so his steps would be as light as he felt. The factory whistle blew for 15 minutes. Signs posted on the doors proclaimed, “Under new management. Charles C. Gates Jr.” The owner proudly passed around cigars and candy, and gave his employees the day off.

“Throw your hat across the creek”

Charles Cassius and John Gideon Gates were born to Gideon and Ruth Ann Gates, and raised on a farm in Michigan. Gideon Gates never studied engineering like he wanted to, but he did plant the idea in his son’s minds. Charles received his engineer of mines degree (with honors) from Michigan College of Mining and Technology, in 1904, with John earning the same degree there in 1911.

Charles came to the Rocky Mountains in 1904, to superintend a mine near Tin Cup, Colo. Lured away by a gold strike in 1906, he worked for the Nevada United Mines Company as a mine engineer; John joined him a few months later as the firm’s assayer.

In 1910, Charles returned to Colorado. Within weeks, he met 18-year-old Hazel Rhoads. On April 4, 1910, six weeks after meeting, the couple married. Mining was in his past.

“My mom told my dad that he couldn’t be out in the mines all of the time and raise a family,'” Gates said.

Charles was sure he was on to something when, in an ad in a local paper, he read: “Rare Manufacturing Chance for an investment of $3,500; can demonstrate that it is more profitable than almost any other legitimate business in the city. Glad to permit thorough investigation.”

After he was shown a stack of promising orders, Charles became the new owner of the Colorado Tire and Leather Company, located at 1025 Broadway, in Denver, on Oct. 1, 1911. The company’s sole product was the Durable Tread, a steel studded leather band that fit over automobile tires.

“It was the forerunner of a recap for tires to extend the life of the tread,” Gates said. “In those days, if you got 500 miles out of tread you were lucky.”

Gates says the company wasn’t that “profitable” after all.

“It was a salted business,” he said, explaining that salting was initially the practice of putting rock salt in shotguns to scare off wild animals.

“During the gold rush period, people would come out and dig a hole in the ground, and get discouraged,” he said. “Then, they would put some gold dust in a shotgun, and blast the wall of the hole, so you could see the gold glitter. They salted it, making it look better than it really was. The next prospective sucker would come along and they’d say, ‘I have to go back East. My mother (or another family member) isn’t well and here I found this great opportunity! I’ll sell it to you for a reasonable price.”

The new owner soon learned that orders he had been shown representing a single day, had in fact been collected over several weeks. Settled into the one-room shop, with his rented typewriter, one employee, and a few pieces of equipment, he valiantly kept his chin up. After all, he was fond of exhorting people to “throw your hat across the creek,” an Old West expression used by pioneers, who, crossing rivers and creeks in covered wagons, threw their hats to the other side as an incentive to cross. This might be a big creek, but he determined to get successfully to the other side.

One of the first things he did was send brother John a set of the Durable Treads, which were promptly placed on the tires of his motorcycle.

“I guess he was going out to the mine one night and had a blow out on the front wheel,” said Gates. “Of course, all those springs and things attached to all this tread got tangled up in the spokes of the motorcycle and he scooted off the front of it and made a burrow in the desert for several feet with his nose. He wrote my dad and said, ‘I think you need some help back there!'”

John Gates shut down the mine, and soon arrived in Denver. Although the product was good, Denver, with about 5,000 cars at that time, would be a hard sell. The brothers worked at coming up with advertising campaigns that would lure customers. When they found a particular slogan that worked, they used it repeatedly. Eight months after the business started, they had 18 employees.

Around Gates’ office on Cherry Creek Drive North in Denver, recognizable by the statue of a bighorn sheep beside the front door, are mementos of “Buffalo Bill” Cody, famed for his Wild West Show, who played a part in the company’s early success.

Not wanting to waste leather scrap, Charles decided to make horse halters.

“They took some of them to some saddle tack shops and they said, ‘Oh no, we make them out of our own scrap,'” Gates said. “About that time, Buffalo Bill rolled into town with his circus. They went out and offered them to his foreman. He said, ‘We have to pull a ton of horses out of the boxcars. Anything that’s free, we can use.’ About a year or so later, they came back into town and said, ‘Those are the best halters that we’ve ever had. Can we get some more?’ My mother said, ‘Yes—if I can get a testimonial from Buffalo Bill.'”

Agreeing, Buffalo Bill proclaimed that the halters were “so strong they never break.” The company was soon the largest halter manufacturer in the West. Hazel Gates pitched in, sewing halters and the fabric lining for the leather treads. Soon, with more space needed, the company expanded to larger headquarters at 1320-40 Acoma.

“You Half-Sole your Shoes; Why Not Half-Sole your Tires?”

In 1914, they acquired six lots at 999 South Broadway, at a time when Broadway, south of 1st Avenue, was a gravel road. But, it offered transportation via streetcar, running down Broadway from Denver to Englewood. Railroad lines were merely two block away.

At a new administration building, halter manufacturing took place on the second floor. A new material also began appearing in products. Rubber was corrosion resistant, resilient, flexible, adhesive, and offered temperature stability. The Half-Sole, a rubber tread on a fabric carcass to be cemented over worn tires—guaranteed puncture-proof and about half the cost of tire replacement—was produced on the first floor. To get the word out, the company advertised: “You half-sole your shoes; why not half-sole your tires?”

Charles’ motto of “Find something that works—then multiply it,” applied to the habit of recruiting customers as sales agents. Soon, the company had customers and salesmen around the country.

The company accidentally entered the automotive belt business in 1915.

“In those days, fan belts were flat leather, spliced together sort of teeth-like,” said Gates. After an employee trimmed the top of a molded rubber-and-fabric bucket he had made in the factory to hold bait, the discarded piece was successfully used as a replacement for a broken fan belt.

A new product for the company, samples of the flat rubber-and-fabric belt were sent to customers. The belt led to John Gates’ invention in 1917 that revolutionized the belt industry. A look under the hood of a new Cole coupe revealed a round hemp rope, acting as a belt, riding in a V-shaped pulley. A problem with this was that the ropes stretched when wet, shrank as they dried and then easily broke.

“My uncle said, ‘Maybe we could make a belt shaped like a V in place of the rope,” Gates said. “So, they tried that out and it worked very well. It gripped the pulley better.”

Twine was dipped in rubber cement, and then coated with fabric and vulcanized in a V-shaped mold. After further testing, the world’s first rubber and fabric V-belt was sent to Cole engineers, who adopted it for their cars.

In 1917, to mirror new products, the Colorado Tire and Leather Company became The International Rubber Company. The entrance of the United States into World War I brought further success for the company. Because the Half-Sole helped conserve rubber, the government classified it as a “priority item.” Sales climbed.

The company was far from average. After an influenza epidemic that swept the country in 1918 resulted in the death of three Gates’ employees, workers were ordered outside each day for fresh air and exercise, while windows and doors were opened to cleanse the air in the factory.

As war continued, employees spent lunch hours and other time at the new Roof Garden, an ornate cafeteria atop the factory with garden walkways, flower boxes, a fishpond and even a porch swing. As they dined, a band played; John Gates participated by playing a mandolin, and later a saxophone. Early rooftop activities included Christmas parties where employees received gifts. Later, Hazel Gates, or “Mommie G,” played Santa Claus to employees’ children. Other activities included birthday parties and wrestling matches.

The company also offered employees discounted products from a gas station at the plant, and later from the Factory Store, which also served local residents. By the end of World War I, the South Broadway factory complex, known as “Gatesville,” also boasted a commissary.

A common sight at the factory over the years was that of several “large” men, and maybe a Model T Ford, hanging from a tire, belt or battery box, to prove a product’s durability.

The end of World War I brought a drop in rubber prices from $1.25 per pound to about 15 cents per pound; complete tires could be sold at a drastic reduction in price. Gates changed with the times. In 1919, the company’s name was changed to The Gates Rubber Company. That same year, warehouses were opened in Chicago and San Francisco. They were soon filled with the Super-Tread, the “tire with the wider and thicker tread.”

Tires received more scientific tests from a unique center-pivot machine located on top of a factory building. Simulated road conditions, such as rail crossings, cobblestones and potholes, tested tires running on a track.

An aggressive advertising push combined with its new product enabled the company to increase its tire sales in 1921 by 40 percent, while due to the crash of the economy tire sales nationwide dropped 35 percent. When the generator was introduced, V-belt sales doubled. Success was furthered by development of 20 different belt sizes, capable of fitting 95 percent of all cars. With other companies now producing the V-belt, Gates held the title of the world’s largest manufacturer.

Growing up in Gatesville

The Gates family increased with the addition in 1923 of Harry Fisher Gates, who bore the name of both his grandfather and his uncle, Harry Mellon Rhoads (H.M. Rhoads, the self-nicknamed “fat photographer,” chronicled history through pictures for the “Rocky Mountain News” for several decades). Berenice Gates was born in 1926.

The family made their home in Bear Creek Canyon, a stretch of canyon between Morrison, Colo., and Idledale, which Gates fondly remembers as being originally known as Starbuck (after developer/entrepreneur John Starbuck).

Living in a house designed by Hazel Gates’ brother and built in 1919, the children were kept busy by various assignments, including catching rodents and picking weeds.

“I think we got a penny a mouse, a nickel a rat, and 25 cents for a pack of dandelions,” Gates said.

After briefly sticking it out (for “maybe one day”) at a school primarily for girls, he began attending Graland Country Day School, originally located in Denver on Colfax Avenue, which he liked much better. In second grade, he shoveled dirt for the groundbreaking of the school’s new location, near First Avenue and Colorado Boulevard.

“There was nothing out there then,” Gates said. “It was prairie. Even in those days Colorado Boulevard wasn’t paved.”

Each day, Charles Gates Sr. made the trek to the factory, stopping to drop the children off at school. As the family grew, so did the size of their car. And, Mr. and Mrs. Gates developed a love for travel.

“They enjoyed the world of exploration,” said Gates. “They traveled around the world by every means you could imagination—boat, mule back and tri-motor airplane.” Most of these trips were made without children.

“They sort of staked us out with a relative or caretaker,” said Gates with a grin.

When Mrs. Gates suggested Hawaii one year, her husband reluctantly agreed; the children not yet in college came along. Much to his surprise, Charles Sr. liked it; this resulted eventually in a second family home there.

Charles Jr. later attended school in both Denver and Hawaii. Although he enjoyed Hawaii, he didn’t like the trip.

“It took a week to get there,” said Gates. “It was two and a half days driving to the West Coast, and then five days and nights by boat.”

Gates said he didn’t weather well on the boats. Due to trouble with ear infections, he had earlier been through a mastoid operation, resulting in the loss of hearing in one ear.

“Today, you don’t hear of that because of penicillin and other antibiotics,” he said. Later in life, he decided that if he couldn’t fly to a destination, he’d rather not go.

After school, Charles Jr. and Harry would often wander around the plant. He remembers loving the smell of crude rubber, immediately evident upon entering the factory, which he says was an “industrial arpege.”

Having a rubber company in Colorado, he says, was a little strange.

“Akron was the place where all the rubber companies were,” he said.

Being around the factory produced a further interest in machinery for the boys. Already, countless hours had been spent on projects their father assigned that were accomplished with tools from a woodworking shop, presented as a Christmas present.

“When you live up there, you have to create your own amusement,” he said.

Items that materialized were a motorized scooter, powered by the reciprocating motor from a washing machine, and a small racing car, made from junked cars, intended to race in the Pikes Peak Hill Climb.

“Dad found it and it disappeared,” Gates said. “He thought we’d get killed.”

As the children grew, so did the company. By 1922, there were 12 distribution points. Over the years, Gates had adopted a manufacturing philosophy of making “necessary accessories to essentials.”

In 1927, Gates built a plant to manufacture garden hose. It soon added radiator hose. When Wall Street crashed in 1929, Gates put more men into the field to develop business. The company was able to maintain profitability. Benefits at the plant also grew. The Gates Mutual Benefit Club, for which members paid club dues of 35 cents per week in the late 1920s, included gasoline and car maintenance as well as medical, pharmaceutical, surgical and dental services. Gatesville had its own clinic and pharmacy. A handful of employees formed a company credit union in 1934.

Following in father’s footsteps

Preparing for this future, Charles Gates Jr., who believes the common language of the world is “mathematics,” made the logical choice of attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Working to earn his engineering degree, he attended MIT from 1939 through 1941. But after two years in Boston, sinus problems led him to transfer to Stanford University.

At the quad at Stanford, one day Gates spotted a “good looking pair of legs.” His eyes traveled upward; two arms, swathed like a mummy, were soon in view.

“That was kind of different,” he said. “I thought, ‘What is that all about?'”

Gates would later find out that the girl with the great legs and bandaged arms had been horseback riding with a boyfriend in Salt Lake City, just before leaving for school, and had embraced a bouquet of poison oak. The two would later meet on a double date, but not as partners. At that time, he realized she was a “really nice person.” Later, he and June, a transfer from the University of Utah, would casually date.

In December 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the nation found itself at war. This would quickly have an impact on the rubber industry. Gates employees, which soon included many housewives, worked six-day, 48-hour weeks to produce rubber products for the home and war fronts, including belts for invasion boats; tires for jeeps, trucks and planes; and parts for bombers, fighters, tanks and ships.

The seizure by Japan in 1942 of rubber plantations in the Malay Peninsula and Dutch East Indies cut off the source of nearly 90 percent of America’s natural rubber supply. The War Department found its stockpile dwindling. Rubber products were searched out for recycling. More importantly, a massive national research and engineering effort was undertaken to produce enough synthetic rubber, previously produced meagerly, to meet the country’s needs. A collaborative government-industry program would soon be in place. Both Gates as a company and Charles Gates Jr. would have a big part in this effort.

After finishing his engineering degree in 1943, he faced the possibility of being drafted. Wanting a say in how he spent the next couple of years, he determined to get into the Naval engineers.

“I didn’t want to be a foot soldier,” he said. Gates, with three (compulsory) years in the Reserve Officer Training Corps in high school, and another two at MIT, partially in the Signal Corps program, thought there might be a little more “family drag” in Denver, and returned there. He took the physical and flunked, due to his deafness in one ear.

“After that, I decided I’d better go to work until I got drafted,” he said. He didn’t immediately begin work for the family business, even though he had spent summers at the factory while attending college.

“My dad decided to farm me out,” he said. “I went with Firestone in Akron. Maybe that was to get a little different picture of the rubber industry.”

While in Akron, he was chosen with about five others to start up a synthetic rubber plant in Louisiana. Established in Baton Rouge in 1943, the Copolymer Corporation was a group of seven medium-sized rubber and tire companies that joined forces to operate one of the U.S. government’s Rubber Reserve plants. Charles Gates Jr. spent three years with the firm as its assistant chief engineer. The push to produce synthetic rubber was a huge success. By 1945, combined efforts resulted in annual synthetic rubber production in the U.S. in excess of 600,000 tons. Before the war, no more than 6,000 tons had ever been produced in a single year.

Gates’ part in the development of synthetics, both through the Copolymer Corporation and at its own factory (they produced the first totally synthetic rubber belt), would help to earn the company the coveted Army/Navy “E” award, presented to a few select Denver firms.

While otherwise occupied, Charles Gates Jr. still thought of the draft. Upon taking yet another physical in New Orleans, he had again flunked. He smiles and says he didn’t understand what difference being deaf in one ear made, what with “all of the cannon fire.”

“Somehow or other they were getting a little fussy about the situation,” he said. “I had five years of ROTC, and I was still a ‘non-wanted.'”

While he waited to be drafted, brother Harry (who attended Menlo College in preparation for Stanford) was. He had been told that if he was drafted, he should make sure he got in the Army, so that he could sign up for the Air Corps. He did.

“Then, they decided they had enough people in the Air Corps,” Gates said. “He was in the Army and it was, ‘You’re on your own now. We don’t want you anymore.'”

After passing the physical, Harry went to boot camp in Texas, and applied for a transfer to the 10th Mountain Division. He got his transfer; however, in a division normally trained in Colorado and famed for skiing, Harry, attached to a desert division, never saw a pair of skis.

“He went from one place in Texas to another and then right into the Italian campaign,” Gates said. Those who made it through the campaign in the Apennines headed off to the Alps for skiing after the war, but not Harry.

“He got pretty banged up over there, and came home in a hospital ship and recovered,” he said.

With the military uninterested in him and his career moving forward, Charles Gates Jr. couldn’t get June out of his mind. Assuming from an earlier conversation that she had plans to go to Mexico City, he wrote her a letter. However, before it could be forwarded and received, he headed there to find her.

“I finally ran her down,” he said. “Finding someone in Mexico City was a pretty big challenge.”

There only a few days, he asked her if she’d like to get married.

“It was on one of the main boulevards in Mexico City somewhere; she said she thought that might be okay,” he said, grinning. “I had to go back to Louisiana to work right away. She came back to Baton Rouge for a couple of days, and then went to Denver. I gave my brother the job of introducing my fiancée to my mother (his father had met her earlier at Stanford).”

Gates and the woman he fondly refers to as “my lady” married in Salt Lake City, on Nov. 26, 1943, and then returned to Baton Rouge. The reunion would be the merging of two distinctly different worlds—that of the “great outdoors” and the “world of culture, including the ballet and symphony.”

“I gave her a shotgun as a wedding present,” he said. “I had her out in the swamps of Louisiana hunting ducks. She was a very good sport. Over the years, I think I did a better job of introducing her to the outdoor world than she did me to the cultural world.”

Gates says that right off, however, he almost “lost her.”

“The first week she got there, she put her foot in a shoe and a big cockroach was in there,” he said. “She wasn’t used to that; I thought she was going to go home to mama right away.”

However, the new Mrs. Gates acclimated well to Baton Rouge. With a population at that time of about 40,000, Gates says it was hot in the summertime, and cool in the winter, and that they loved the people and the location. Baton Rouge brought another change into his life.

“While there, I started looking for something to do,” he said. “I always wondered how birds fly. I decided to take flying lessons.”

Gates says that on a mandatory cross-country, he overshot his first airport.

“I ran out of gas when I finally landed at the airfield,” he said. “I was 75 miles farther up the river than I wanted to be.”

June was unaware of his new pastime.

“My lady started asking me why I was always late getting home from work,” he said. “Finally, I told her I had a surprise for her. I took her out to the airfield and managed to talk her into getting into the backseat of an open-cockpit airplane. I gave her a pair of goggles and a scarf and we took off.”

That would not be the end of his association with aviation, but, in the meantime, in June 1946, the couple returned to Denver, and he entered the family business. He says he began as a “hired hand,” and then smiles.

“Actually, I was a hired hand for 50 years,” he says. Gates quips that he didn’t start out in the business on the ground floor, but in the basement, where he hauled sooty substances, requiring the “need of several showers a day.” He jokes that good friend and longtime employee Ben Duke, who, like brother Harry, served in the 10th Mountain Division, started with the company before he did and always said he had “more seniority.” If there were bad times, Duke said, Charles Jr. would go first.

While Charles Jr.—who would become vice president of the company in 1951—focused on marketing and finance, Harry—also a new Gates employee—put his efforts into manufacturing, engineering, and research and development. He would provide the company with over 30 patents.

“We sort of teamed together,” Gates said. “He was a very people person, as were my father and my Uncle John.”

During and after the war, Gates hired dozens of chemists, physicists and engineers, which developed compounds and found new uses for synthetic fibers, such as rayon and nylon, as reinforcing materials.

In 1954, the company saw sales of $82 million. Denver’s largest firm, it was also the nation’s sixth largest rubber company. By that time, Gatesville included more than 30 interconnected structures, on a 53-acre site. That same year, a manufacturing facility was opened in Brantford, Ontario, Canada.

The Gates family celebrated births and mourned losses over the next few years. Charles and June produced daughter Diane in 1954 and son John in 1956.

In 1955, Harry Fisher Gates, who had married “Mitten” Howell in 1949, succumbed to cancer, at the age of 32. John Gideon Gates, who served as secretary-treasurer of the company throughout the years, died in 1959. Charles Gates Sr. died in 1961, at the age of 83, leaving a still private empire with sales totaling $140 million, which employed 7,300 and distributed around the world.

The Gun-Slinging Years

Upon the death of his father, Charles Gates Jr., 40, stepped into his father’s shoes as president and chairman of the board. In so doing, he shed the title of executive vice president, which he earned in 1958, the same year Gates Rubber de Mexico opened in Toluca, Mexico.

Since then, growth had continued with new plants and warehouses. Although his father had expanded the company with an ever-increasing list of products, Charles Gates Jr. believed there was room for change.

“The rubber business was growing about two or two and a half percent a year,” he said. “I thought we needed diversification to have more grow power.”

The company began staking out other fields of interest.

“That was the beginning of our gun-slinging years,” he said. “Shooting from the hip,” Gates analyzed and entered different ventures, knowing that, in many cases, others thought he had “lost his marbles.” And, he encountered problems.

“We kept running into ourselves out there in the marketplace, because we were supplying rubber products to the industrial, hardware and automotive worlds,” he said. “The things that seemed logical to get into always competed with our customers.”

At the time in the hydraulics hose business, Gates thought that the farming industry was worth a venture.

“I became intrigued with these rotary-rigged overhead irrigation systems, like you see a lot of in eastern Colorado,” he said. “We put a team together to find out where the best sub-surface water was. We started to acquire this dry land and found out that it was some of the best sub-surface water anywhere in the country. But soon, the agricultural industry, which we were supplying products to, said, ‘You’ve got the farmers cranked up here. They’re starting to think of you as a big industrial farmer out here taking the livelihood of all these little farms away. International Harvester, John Deere and others had Gates’ products on them. The farmer’s co-op started talking about the fact that they shouldn’t buy our products. The industry said, ‘You have to decide if you’re in the rubber business or the farming business.'”

The trend continued.

The proud father (holding his new son, and leaning back in his chair) celebrated the birth of Charles Cassius Gates Jr. with employees.

“I think we tried to get into almost every kind of business,” he said. “Then I thought, ‘Well, what would make sense would be to create—along with the other things—a chain of garages across the country. If you had your car repaired in Denver, you could guarantee it in Salt Lake City or somewhere. You could go to one of these places to get it repaired.”

Almost as soon as he had the idea, he realized that there was still a problem.

“If we got into that business we would be competing with all of the little garages that we were supplying,” he said. “Another business we got into was the trucking business.”

This might have given Gates something further to talk about with good friend Jerry McMorris (principal of the Colorado Rockies), former president, chairman and CEO of now defunct NationsWay Transport Service Inc., but it also got people riled up again.

“We were running our own little truck line, taking products out and raw materials back,” he said. “The trucking industry said, ‘Well, if you’re going to compete with us, we shouldn’t be buying your tires and other products.’ We decided we were still going to use trucks to haul stuff around, but have a very small operation.”

That idea spawned another.

“I finally decided, ‘I think aviation is where it is,” he said. “I thought, ‘Well, maybe this idea of creating automotive garages wasn’t so good but what about aircraft garages across the country?’ I thought aviation was going to come into its own. The highways were getting crowded.”

Next month, read how Charles Gates Jr. propelled the corporation into the ranks of America’s top privately owned companies, and joined forces with aviation icons Harry Combs, Bill Lear and Roscoe Turner.

Charles Gates Jr.—Born in Motion (part 2)