The year is 1935. As Pan American Airways plans its historic attempt to conquer the Pacific, the world is in a deep economic depression. Franklin D. Roosevelt has just been elected president of the United States—and will remain so for an unprecedented four terms. Only 48 states are in the Union; Alaska and Hawaii will not be added for almost 25 years. Prohibition has been repealed, and thanks to Hollywood, New York’s Empire State Building will forever have King Kong associated with it.

The establishment of Pan Am’s transpacific route, a mere 32 years after the Wright brothers’ Kitty Hawk success, overcame the greatest technological, geographical and navigational challenges of the day. Its fleet of flying boats captured the world’s imagination as it ushered in the age of global air travel. Today people cross oceans in airplanes without even a second thought, but in November 1935, that very first transoceanic commercial airliner flight was a mammoth undertaking that presaged modern international travel.

November 2010 will mark the 75th anniversary of that inaugural China Clipper flight, which opened the Pacific to the world’s first regular transoceanic commercial air service. The San Francisco Aeronautical Society, a nonprofit volunteer organization dedicated to preserving the history of aviation, in conjunction with the Pan Am Historical Foundation, is organizing a unique event commemorating what is generally regarded as the greatest milestone in commercial aviation history.

The China Clipper 75th Anniversary Flight will depart from San Francisco to retrace the historic Pacific route that reached Hong Kong via Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Guam, and Manila—albeit with a modern aircraft outfitted entirely in first class format. Exclusive VIP functions will be held at each port of call.

History

The British government blocked Pan Am’s use of intermediate bases in Newfoundland and Bermuda until a British airline could be made ready for reciprocal service—a desire that never materialized. So, Pan Am turned its attention to the Pacific. Survey flights to Asia had begun in 1931, when Col. Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, made a flight along the Great Circle route from New York to Nanking, China, via the Arctic. Though successful, their epic journey exposed insurmountable challenges, both diplomatic and meteorological. Therefore, it was in the middle latitudes that Pan Am would create the first transpacific route.

A Boeing B-314 flies over San Francisco Bay, with the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge on the lower left and Yerba Buena Island and Treasure Island on the lower right. The harbor between, Port of the Trade Winds, was the home port of the flying boats.

Searching his globe for the steppingstones needed to link a route across the planet’s greatest water gap, Juan Trippe, Pan Am’s president, began plotting the route to Asia. Apparent were Hawaii and the Philippines, with the inevitable jump from there to China. Midpoints in the Hawaii-Philippines sector could be Guam and Midway Island. This still left a gap of more than 2,800 miles.

In studying 19th century clipper ship logs in the New York Public Library, he found a little-known coral atoll named Wake Island. With a series of island bases between San Francisco and Manila in the Philippines, the longest sector of the 8,210-mile airway would be the 2,410 miles from San Francisco to Honolulu.

After specifying and ordering aircraft capable of the route, and while conducting a series of survey flights, Pan Am constructed the facilities for air bases and overnight passenger accommodations at the mid-Pacific points. Two of them, Midway and Wake, were built from scratch. In early 1935, the 15,000-ton steamer North Haven was loaded at San Francisco’s pier 22. It would carry prefabricated structures for two complete villages and five air bases, a quarter of a million gallons of fuel, 44 airline technicians, 74 construction workers and 32 ship’s crewmen. Heavy equipment, such as motor launches, barges, tractors, refrigerators, diesel electric generators, windmills, water storage and gasoline tanks, radios and direction finding equipment and even a small-gauge train were also taken. A ton of dynamite was added in Honolulu to clear the lagoons for flying boat operations.

Pan Am’s fabled China Clipper, a Martin M-130 flying boat, left Alameda on San Francisco Bay on Nov. 22, 1935. Under the command of Capt. Edwin C. Musick, the flight would reach Manila six days later via Honolulu, Midway, Wake and Guam. The inauguration of ocean airmail service and this first commercial air route across the Pacific were significant events for both the U.S. and the world.

Trippe, the airline’s visionary leader, suggested the use of “clipper” names for Pam Am’s fleet of flying boats. He saw this new class of long-range aircraft as modern age versions of the swift 19th century clipper ships that plied the trade routes of the world. In reality, they did share many of the design challenges faced by marine architects, with respect to buoyancy, hull contours and general seaworthiness. Their flying capabilities made them true hybrids during this period of transition from surface to air transport.

The sea wings or sponsons on the Martin M-130 provided improved stability on the water over outboard floats plus the added advantage of each carrying 950 gallons of fuel.

The Pan Am “Flying Clippers” title became one of the most distinct and famous brand names in aviation history. The maritime references and advertising slogans, such as “aircruise,” conjured up images of sailing through the skies to distant and exotic shores. The terminology and navy blue uniforms of the flight crews reinforced this aura. In many ways, operating procedures were actually based on naval standards. The highly skilled crews were cross-trained in navigation, both celestial and in the new radio direction finding technology. The rank of captain was given to the commanding officer, and a first officer, second officer, flight engineering officer, flight radio officer, purser and steward rounded out the crew. Pan Am certified qualifying pilots as “masters of ocean flying boats.”

Pan Am pilots were among the most experienced aviators of their day, and the early flight crews and ground personnel set the standards in airline operation. Musick was an Army Air Corps flyer during World War I and one of the first pilots to accumulate 10,000 hours of flying time. He joined Pan Am in 1927 and soon became the chief pilot. He flew the first survey flights to Guam and New Zealand in the S-42 and the inaugural airmail and passenger flights from San Francisco to Manila in the M-130. Andre Priester, chief engineer and operations manager, developed the airline’s strict standards and the concept of multiple flight crews, whereby all personnel were trained in navigation, radio operation and engineering.

Meteorology, radio and navigation

During the departure of the first survey flight on April 16, 1935, San Francisco Bay–Honolulu, a Sikorsky S-42 flies over the pylons of the yet to be completed San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge.

Pan Am developed the Pacific’s first weather maps, known as “synoptic” charts, and developed systems for reporting and forecasting upper air conditions. The company then built weather-reporting stations at the Pacific bases. Matson Navigational Company’s ocean liners provided additional information. Hugo C. Leuteritz, Pan Am’s chief of communications, directed the development of radio technology for communications and direction finding. Government-licensed operators staffed aeronautical radio installations. Aircraft were fitted with state-of-the-art equipment. Direction finders were used for navigation, but early systems could give only single line positions. Celestial bubble sextants and octants were used, and an aircraft pelorus-type compass was developed for positioning and navigation.

Transpacific airmail

Foreign airmail routes, awarded by the U.S. government, were essential to Pan Am’s development. A contract with the Postal Service allowed an airline to gain valuable operating experience over routes that would be used for income-generating passenger service. The first flight envelopes, or “covers,” trace the milestones in establishing the Pacific routes; the crews signed some covers. Special stamp imprints, or “cachets,” commemorate first flights. The survey flights, though not scheduled airmail runs, carried empty envelopes stamped with the earliest cachets designed by Pan Am personnel. The inaugural China Clipper flight from San Francisco Bay to Manila Bay carried 110,865 letters outbound and returned with 98,480 pieces of mail.

Passenger experience

Comfort was a priority from the earliest stages of Pan Am’s passenger service. Aircraft interiors were designed to provide ample room and amenities for the long distance traveler. Passenger levels had spacious lounges with seats and sleepers, dressing rooms, a dining room and even a deluxe honeymoon suite—over 70 years before Airbus introduced private suites on its A380. In 1936, the 8,210-mile flight from San Francisco to Manila took six days, with a total flying time of about 60 hours. The round trip fare was $1,710, equivalent in today’s dollars to about $25,000. At each island base stopover was a Pan American Airway Inn with port stewards, chefs and attendants, to maintain a high standard of service for the overnight guests.

Juan Terry Trippe

Juan Trippe was Pan Am’s founding president and the driving force behind the development of international air travel. He built the company from an airline with a 90-mile route between Key West, Fla., and Havana in 1927 to an organization with an 80,000-mile route system linking the U.S. with 85 countries on six continents at the time of his retirement in 1968. Recognition of his achievements includes 26 decorations from 19 foreign nations; the U.S. Medal for Merit, the government’s highest civilian award; all 10 major aviation awards, among them the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy, the Collier Trophy and the Harmon Trophy; and 29 other awards for his contributions in the fields of business, trade, education and social service. Under his leadership, Pan American inaugurated the first commercial flights across the Pacific and the Atlantic and the first scheduled flight around the world. He pioneered the development of new and advanced transport aircraft, established a global air system and set the operating standards of the commercial aviation industry.

Aircraft

Capt. Edwin Musick and R.O.D. Sullivan next to the China Clipper before leaving San Francisco Bay with the first transpacific airmail. On the ground, L to R: Postmaster Gen. James Farley, Asst. Postmaster Gen. Harllee Branch and Pan Am Pres. Juan Tripp.

The Glenn L. Martin Company of Middle River, Md., produced three model M-130 flying boats, the first successful transoceanic intercontinental airliners. They were designed to Pan Am’s specifications for long haul, over-water service, with payload capacity and cabins outfitted for passenger comfort.

As Pan Am’s Sikorsky S-42 flying boats had proved so effective in the Caribbean and in surveying the Pacific route, the Martins proved their worthiness in opening the Pacific to scheduled service. Only three of the M-130 models were made, all for Pan Am, each costing $417,000. They served admirably, yet each met a fateful end. The Hawaii Clipper disappeared without a trace on a scheduled flight between Guam and Manila in 1936. The Philippine Clipper was lost in a mountainous crash on a military flight during WWII; it overshot the California coastline in zero visibility conditions. The China Clipper, affectionately dubbed “Sweet 16” by its crewmembers for the last two numbers of its registry, flew numerous scheduled flights as well as military missions in both the Pacific and the Atlantic, including a shipment of uranium ore from Africa for the Manhattan Project. At the close of WWII, it sank at Port of Spain, Trinidad, after more then three million miles of service.

The need for increased capacity followed the success in Pan Am’s pioneering of over-ocean air transport. The Boeing Company of Seattle secured a contract with Pan Am to produce a flying boat of unprecedented size and luxury. At an initial cost of $550,000 each, Boeing would produce 12 B-314 models, the largest commercial aircraft of its day. Pan Am ordered all of them. However, three of the giant ships the press called “flying hotels” were sold to the British before delivery, to satisfy their transatlantic needs. Upon delivery of the first batch to Pan Am in 1939, the B 314 went into service on the Pacific and opened the North Atlantic route the same year. The spacious cabins, which included a bridal suite in the tail, set the new standard in the quality of the passenger experience.

The B-314 used the wings and engine nacelles of the giant Boeing XB-15 bomber. New Wright 1,500-hp Double Cyclone engines eliminated the lack of power that handicapped the XB-15. With a nose similar to that of the modern 747, the Clipper was the “jumbo” airplane of its time.

Dining service aboard a Pan American Airways Boeing B-314 in1939 set standards in comfort and luxury that may even be unequaled today.

The B-314 also took up the wartime role of what would now be considered Air Force One. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the first commander-in-chief to fly while in office, traveled aboard the Dixie Clipper with additional staff trailing in the Atlantic Clipper, on a top secret flight to confer with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Casablanca, Morocco. Churchill, also a frequent B-314 passenger and an enthusiastic fan of the giant flying boat, even took a turn at the controls.

The aeronautical design genius Igor Sikorsky, who had fled his native Russia in 1917, had long envisioned large, multi-engine aircraft. In partnering with Trippe and Lindbergh, now the airline’s technical consultant, Sikorsky’s dreams were fulfilled. His earlier S-38 had been hugely successful in early establishment of Pan Am’s routes throughout the Caribbean and Central and South America. The launching of the much larger, four-engine S-40 model in 1931 led to immediate planning among the three for a flying boat capable of spanning the oceans. The Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation of Stratford, Conn. answered with the S-42 model. Considered a true airliner, it was put into service on the Miami to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil route and gave Pan Am superiority over all competitors. When it came time to prepare the Pacific route, the S-42 was chosen and modified for the rigorous survey flights. It became a workhorse of the Pacific and Atlantic for both survey and regularly scheduled duty.

San Francisco Aeronautical Society

The San Francisco Aeronautical Society’s board of directors includes many well-known and respected aviation personalities such as Zoe Dell Nutter, National Aviation Hall of Fame trustee emeritus and Living Legends of Aviation honoree; Jean Tinsley, NAHF life member, co-founder of the Helicopter Club of America and executive director of Whirly Girls; and Marion Wright, a member of the Wright family and a former trustee of the NAHF. Louis A. Turpen, the board president of the San Francisco Aeronautical Society, is the former CEO of San Francisco International Airport and Toronto Pearson International Airport, a fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society in Great Britain and a member of the NAHF board of nominations.

The society was founded in 1997 as a nonprofit organization to serve as the affiliated support group of the San Francisco Airport Commission Aviation Library and Louis A. Turpen Aviation Museum. This unique facility, located at San Francisco International Airport, opened to the public in December 2000. As a collecting institution for research and exhibition programming, its purpose is to enrich understanding of past, present and future achievements in air transport.

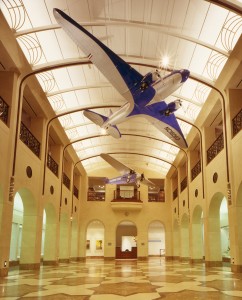

The lobby of the San Francisco Airport Museum is an authentic recreation of the original 1937 terminal building. Hanging from the ceiling are one quarter-scale models of the Kingsford Smith’s Southern Cross Fokker Trimotor and a United DC-3.

An extensive library contains approximately 6,500 books on commercial, civil and military aviation, including fiction and juvenilia, 150 active subscriptions to aviation periodicals and more than 2,000 aviation and general interest magazines in runs from the 1890s to the 1980s. Technical manuals, ephemera and unique publications are maintained in subject files. Archives include photographs, architectural drawings, design drawings, maps, charts and philatelic materials.

An active oral history program produces transcribed interviews that are part of the library collection. These provide first-person accounts from individuals who have experienced careers in aviation. Subjects include airport administrators, airline executives, airline pilots and flight and ground crew personnel.

The museum holds more than 12,000 objects. Three-dimensional artifacts relating to commercial aviation in the Pacific include airport equipment, architectural elements, building materials, furnishings, aircraft equipment, uniforms, in-flight service wares, graphic design works, posters and promotional materials.

For further information on the 75th Anniversary China Clipper Flight, visit [http://www.chinaclipper75.com].