By Di Freeze

Unlike many aviators Chuck Yeager would meet throughout his life, he never dreamed of flying while he was growing up in West Virginia, in the Appalachian foothills.

“I run into guys that say, ‘I hung on a fence, and looked at airplanes; I really wanted to be a pilot,'” he said. “Hell, airplanes meant nothing to me, because I didn’t know what they were. Basically, even after I got into the military in ’41, at age 18, I was just a mechanic and, flying, I just wasn’t interested in it. It wasn’t my world.”

His “world” was doing whatever he enjoyed. It helped that what he enjoyed, he did well. It wasn’t just his history, but also the way he told it, that captivated Ian Ballantine, Bantam Books founder, when he heard Yeager speak in the early 1980s. Afterwards, he told Yeager he should write a book.

“I said, ‘I’m not a book writer; I’m a test pilot,'” recalled Yeager. “He said, ‘No, you really should get this down.'”

For the multimillion copy bestseller, “Yeager,” an autobiography by Yeager and Leo Janos (editor), Yeager utilized an oral history manuscript he made when he retired, and at the suggestion of Ballantine, incorporated “Other Voices,” through which others tell their recollections.

Charles Elwood “Chuck” Yeager was born on Feb. 13, 1923, to Albert Hal Yeager and Susie Mae Yeager. His earliest years were spent in Myra, W.Va., a small town a few miles up the Mud River from Hamlin, and in Hubble, where Albert Yeager worked for the railroad. When Yeager was still in preschool, his father began drilling for natural gas, and they moved to Hamlin, with a population of about 400.

Later in life, Yeager would be glad he inherited the mechanical aptitude of his father. Growing up around truck engines and drilling equipment, he was one of the few children who could take apart a car motor and put it back together again.

By the time Yeager entered high school, he excelled at anything that demanded dexterity or mathematical aptitude. He graduated from Hamlin High School in 1941. While his family wasn’t destitute, money was hard to come by, so he never considered going to college.

“I wasn’t much of a scholar, but I was always eager to acquire practical knowledge about things that interested me,” he said.

In the summer of 1941, an Army Air Corps recruiter came to town, and Yeager enlisted for a two-year hitch.

“I thought I might enjoy it and see some of the world,” he said.

His first job in the military was as an airplane mechanic, stationed at Moffett Field. There, a notice on a bulletin board regarding the Army Air Corps’ Flying Sergeant program caught Yeager’s eye.

“Cadets had needed two years of college and had to be 20 years of age,” Yeager said. “They weren’t getting enough applicants, so they opened it up for aviation students. That’s what they called us, instead of aviation cadets. Basically, what that meant was that if you had a high school diploma and were age 18, you could apply for pilot training, but you would not be an officer when you graduated. You’d be a staff sergeant.”

Although Yeager wasn’t interested in flying, the deal sounded inviting.

“We were busting our knuckles working on airplanes,” he explained.

Yeager remembers the day he was called in for his physical.

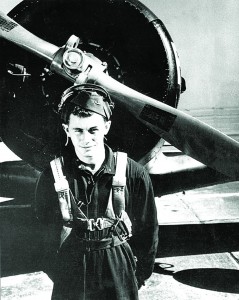

“I was crew chief on T-6s, and I was working on them as I was called in,” he said. “I took my physical on the fourth of December, right before the war started. It took about six months for them to call me for flight training.”

Up until that point, Yeager had never flown.

“I finally took a ride at Victorville, in an AT-11 twin-engine Bombardier trainer that I was crew chief on,” he said. “Man, I puked all over; I was so sick. When I landed, I’ll never forget, I said, ‘Yeager, you made a big mistake!'”

Yeager was called for pilot training in the summer of 1942.

“When I started flying the airplane, instead of just riding in it, I had no problem,” he said.

The 363rd Fighter Squadron

Yeager completed primary pilot training at Hemet, Calif., followed by basic in BT-13s at Gardner Field in Taft, Calif., and advanced training at Luke Field, Ariz., where he earned his pilot’s wings with Class 43-C on March 10, 1943.

He joined the 363rd Fighter Squadron at the Tonopah Bombing and Gunnery Range, Nevada, later that month, and began training in fighter tactics in the Bell P-39 Airacobra. When he reported to the 363rd FS, it wasn’t as a flying sergeant.

“By then, the regulations had changed, and those of us receiving our wings as enlisted men were made noncommissioned flight officers, wearing blue bars instead of gold,” he said.

Yeager was among 30 pilots in the 363rd that began six months of intensive training at Tonopah in preparation for combat. He logged 100 hours in the Airacobra during his first month.

“When I became a fighter pilot, I couldn’t imagine being anything else,” he said.

In late June, he left Nevada to begin training in bomber escort and coastal patrol operations at Santa Rosa, Calif. After a temporary assignment as a test pilot at Wright Field, doing accelerated service testing on a new propeller developed for the P-39, he returned to California the day his squadron flew from Santa Rosa to Oroville, Calif., the next stop on their training schedule.

On his first day in Oroville, Yeager went to a local gymnasium to arrange a USO dance, and met 18-year-old Glennis Dickhouse, the pretty brunette social director. He asked if she could arrange a dance that evening for about 30 men.

“You expect me to whip up a dance and find 30 girls on three hours’ notice!” she exclaimed.

“No, you’ll only need to come up with 29, because I want to take you,” was Yeager’s reply.

She arranged the dance, and accepted Yeager’s offer. The evening wasn’t without difficulties. He said it was tough to make small talk with her because she complained she couldn’t understand his West Virginia accent.

“When I met her, she had three jobs, and every one of them was making more money than I was,” he recalled. “I was only getting $150 a month.”

Just one of the things the two had in common was that she was a good shot.

“She was raised on a ranch and liked to hunt, fish and swim,” he said.

Glennis Dickhouse, Yeager said, was as “tough and gutsy as she was good-looking.” When he left Oroville, she gave the maintenance officer her picture and they promised to write.

From there, it was on to Casper, Wyo., for the final phase of training. While there, Yeager was hospitalized briefly with a fractured back. His injury occurred when he bailed out of his P-39 after the engine blew and his plane burst into flames.

Combat And Evasion

In late November 1943, the 357th FG sailed for England. Based at Leiston, 60 miles up the coast from London, the 357th was the first unit in the 8th Air Force to employ the P-51 Mustang.

The group logged their first combat mission on Feb. 11, 1944, but didn’t encounter fighters that day. Yeager scored his first aerial victory on March 4, when he downed a Messerschmitt Me-109 over Berlin. However, he had little time to celebrate. The following day, on his eighth combat mission, during a raid on Bordeaux, France, he was shot down.

“I found out I wasn’t so shit hot,” said Yeager.

On the morning of March 5, 18 Mustangs took off from the British coast to escort B-24s on their bombing run. Four flights of four P-51 Mustangs provided air cover; the other two Mustangs would join the mission only if there were aborts. Yeager, flying Glamorous Glen, was one of those extras; when a Mustang from one of the flights turned back over the Channel with engine problems, he pulled in as the fourth plane—tail-end Charlie.

When he saw three Focke-Wulf 190 fighters diving at him, he radioed a warning, and his flight turned to meet the enemy head-on. Soon after, the 20-millimeter cannons of a Focke-Wulf 190 hit Yeager’s aircraft.

Yeager was barely able to unfasten his safety belt and crawl over the seat before his burning P-51 began to snap and roll, heading for the ground. Once on the ground in the countryside of the occupied territory of southern France, Yeager gathered in his parachute, and limped off into the woods, pausing long enough to treat shrapnel punctures in his feet and hands. Studying a silk map of Europe sewn into his flight suit told him he was about 50 miles east of Bordeaux.

Yeager hid in the woods that night. The next morning, when he peeked out from under his parachute, he saw a woodcutter with an ax. Yeager emerged, brandishing his pistol. Correctly assuming there would be a language problem, he forcefully said, “Me American. Need help. Find underground.”

The woodcutter hurried off into the forest, and Yeager went back to his hiding place. More than an hour later, he heard a voice.

“American,” the voice said. “A friend is here. Come out.”

The “friend” was an old man whom Yeager followed through the woods to a stone farmhouse. There, in a storeroom in the hayloft, he would hide for nearly a week. Then, Yeager was accompanied to the village of Nerac, a few miles from Roquefort, where he would stay for the next few weeks. He was next taken to the Maquis, a group of about 25 French resistance fighters. Yeager lived with them until the weather was good enough to attempt crossing the Pyrenees Mountains into neutral Spain.

On an afternoon in late March, Yeager was transported by van, along with some other evadees, to an area outside Lourdes. From there, he and a B-24 navigator who was shot down over France would cross the Pyrenees, with the help of a hand-drawn map. On the fourth day, while they slept in an abandoned cabin, a passing German patrol spotted the navigator’s socks drying on the outside, and riddled the cabin with bullets. The two men escaped through a rear window.

Grabbing his wounded companion, who had been shot in the knee, Yeager sailed down the hill on a makeshift slide, before splashing into a creek several thousand feet below. When Yeager found that a single tendon was the only thing holding together his companion’s upper and lower leg, he cut that tendon with a penknife, and tied a piece of silk around the stump. Once in Spain, he deposited the unconscious navigator beside a road, where he hoped a passing motorist would find him (he was found and later repatriated out of Spain).

After that, Yeager walked south for another 20 miles, until he reached a small village, and turned himself in to the local police. When they locked him in a jail cell, his longing for a hot bath, meal and warm bed were so strong that he pulled a small saw out of his survival kit and cut through the brass bars. He found a small pensione a few blocks away, ate, soaked for an hour in a hot tub, and slept for two days, until the American consul knocked on his door, early in the afternoon on March 30, 1944.

For the next six weeks, Yeager lived in a resort hotel while the American consul negotiated to free him and five other downed airmen. They finally succeeded, by trading gasoline for the evadees.

Yeager returned to Leiston in the middle of May 1944, suntanned and healthy, the first in his squadron to make it back as an evadee. However, it didn’t look like he’d be there long.

“A rule had been established that once you were shot down, you were finished with combat,” he said. “They were afraid that if you got shot down again and the Germans captured you, they would sweat the underground system out of you, and there would be a lot of innocent Frenchmen killed.”

Yeager was to return to New York on June 25. Until then, no one had ever challenged the rule. However, Yeager wasn’t ready to go back to the States. He began pleading his cause to various colonels and generals at SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe).

One day, he and a bomber captain named Fred Glover, who had evaded back through Holland, met with a two-star general. He listened to their arguments, and then said that only Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower could decide the matter. Finally, they had their audience with the commander.

“I raised so much hell that General Eisenhower finally let me go back to my squadron,” Yeager said. “He cleared me for combat after D Day, because all the free Frenchmen—Maquis and people like that—had surfaced.”

Years later, Yeager and Eisenhower became good friends, through their mutual acquaintance, Jackie Cochran, and the subject of his battle to stay in combat came up. Yeager recalled Eisenhower saying, “I normally wouldn’t have seen guys like you, but I wanted to find out why the hell you wanted to go back into combat; I had guys shooting themselves in the foot to go home.”

Ace In A Day

Yeager resumed combat operations in August. Even before that, he shot down an enemy aircraft, but he wasn’t officially credited for it.

Before his traveling orders were rescinded, Yeager had strict orders to avoid combat. He was allowed to fly locally, which included base defense. Soon after his return to England, he was flying over the base when the control tower ordered him to lead three others out over the North Sea, near Heligoland, to provide cover for shot down B-17 crewmen awaiting rescue in a dinghy. While he and the others circled, he spotted a Junkers Ju-88 approaching. Instantly, he headed toward the aircraft, and when it turned to run, followed and shot it down. When he reported the incident to the squadron’s operations officer, he was scolded and grounded. Another pilot was given the credit for the victory.

With still only one air victory officially credited to him, Yeager was soon one of four squadron flight leaders. He was the only one who wasn’t an ace, and the only one that wasn’t a commissioned officer.

Yeager had been denied promotion to lieutenant three times. The reason was because of a court-martial when he was a corporal. While on guard duty one night, Yeager was showing someone how to fire a 30-caliber machine gun by shooting bursts out into the desert. Thinking he was firing short, he shot a grazing horse and killed it; the owner demanded that the Air Corps pay for it.

When group headquarters chose him to lead the group, Yeager was 21 and still the most junior officer in the squadron. By then, there were more than 20 aces in the three squadrons comprising the 357th Fighter Group.

Yeager said that he and good friend Maj. Clarence “Bud” Anderson—who piloted Old Crow and would end up as the leading ace of the 363rd FS, with 17 kills—were the only ones in their squadron gifted with “combat vision.” He explained it as being able to “focus out to infinity and back, searching a section of sky each time.”

That vision came in handy on October 12. On that day, while flying his P-51D on a bombing escort over Bremen, Yeager scored five victories, becoming the first “ace in a day” and earning a Silver Star.

In the engagement with 22 ME-109s, the squadron scored a total of eight victories. Ironically, when Yeager closed in on one enemy aircraft, the pilot broke left and collided with his wingman; both bailed out, earning Yeager credit for two victories without firing a shot.

That was actually one of the smaller engagements they had.

“All through the combat, we had lots of big dogfights,” Yeager said. “Some days, there would be 200 German fighters against our 48 Mustangs, but we were very good. The Germans, we pretty much wiped out their good guys.”

Yeager said that by the fall of 1944, the average number of missions German fighter pilots flew before getting killed was three.

“That’s a high attrition rate, but we had excellent airplanes,” Yeager said. “We were deep in Germany flying eight-hour missions, and they were only flying missions of one hour, 20 minutes; they weren’t very experienced.”

Yeager said some German pilots were shot down a couple of times a day.

“Hell, Günter Raul, who shot down about 220 to 230 airplanes, got shot down seven times,” he said.

During combat, said Yeager, he wasn’t the only one who developed a fatalistic attitude.

“We had about 30 guys in our squadron when we went over there, and 21 of them got killed,” he said. “But you think, ‘What the hell, it’s my duty,’ and you don’t question it. Hell, if you get killed, you don’t know anything about it anyway.”

Yeager scored one victory when he flew through dense flak to shoot down one of the first Me-262 jet fighters, as it was lining up for a runway landing at a large German airdrome. That earned the pilot a Distinguished Flying Cross. Then, on November 27, during an historic dogfight, he shot down four FW-190s.

Anderson and Yeager worked it out that they would complete their missions on the same day, go home together, and hopefully be reassigned to the same base. On the morning of Jan. 15, 1945, Major Anderson and Captain Yeager flew their last mission together.

“Andy was an ops officer; he scheduled us as spares,” Yeager said.

When nobody aborted on what they assumed would be a milk run, the two took off for a little sightseeing. Yeager planned to show his companion his evasion route.

“We broke every damn rule,” Yeager said. “We were down over Switzerland, a neutral country, and they had Swiss 109s. They wouldn’t send them up. We dropped our tanks on Mount Blanc. We fired all of our ammunition and we strafed our tanks.”

Their journey also took them over parts of France, Italy and Spain. The men were up in the air about eight hours. When they returned, squadron members rushed to meet them, excitedly firing questions at them, including, “How many airplanes did you shoot down?”

Yeager and Anderson hadn’t heard any radio transmission because they were too far away, so they didn’t know about the huge dogfight that had occurred.

“The group shot down 56 fighters,” Yeager said. “We felt bad, but then we said, ‘What the hell, we might have gotten shot down too.'”

Yeager returned to the States as a double ace with 13 victories (including the Ju-188). He had completed 64 combat missions, with a total of 270 combat hours.

In all, the “Yoxford Boys” were responsible for shooting down 609.5 enemy aircraft in only 15 months and yielding 42 aces, more than any other fighter group.

Wright Field

Although he hadn’t officially proposed, Yeager arrived at Glennis’ door in California and promptly told her to pack her bags, because she was going home with him to meet his folks. After getting the blessings from her parents, the two married on Feb. 26, 1945.

As they had hoped, Yeager and Anderson were assigned together, as instructors at Perrin Field in Texas. But when a new regulation was announced allowing former prisoners of war or evadees to select an assignment at the base of their choice, Yeager chose Wright Field, in Dayton, Ohio. Glennis was expecting their first child, and Wright Field was the closest base to Hamlin and his family.

Wright Field, said Yeager, was the most exciting place on earth for a fighter pilot. Not only were the hangars crammed with airplanes begging to be flown, but also, it would soon be the center of the greatest adventure in aviation since the Wright brothers: the conversion from propeller airplanes to supersonic jets and rocket-propelled aircraft.

In August 1945, Col. Albert G. Boyd, the head of the flight test division, requested that the maintenance officer accompany him and a detachment of fighter test pilots to Muroc Air Base in the Mojave Desert. They were to conduct service tests on Lockheed’s P-80A Shooting Star.

Impressed with Yeager’s flying and maintenance abilities, Boyd asked him to fly one F-80 back to Wright. That drew protest from the major in charge of the fighter test section, who thought a test pilot should fly it back. But Boyd stuck to his decision, saying that Yeager understood the system.

Yeager remained self-conscious about his lack of education, especially in comparison to the test pilots. With jets coming into the picture, flying would get more complex and technical, and he worried about keeping up without an engineering background. Still, he wasn’t particularly impressed with the skills of the fighter test pilots. After the service tests at Muroc, they felt even worse about him, he said.

Shortly after arriving back at Wright Field, Yeager met “one of the best fighter pilots and finest aerobatic pilots that ever flew an airplane.” One day, while he circled the field in the Bell P-59 Airacomet, America’s first jet-propelled airplane, a P-38 prop fighter dove on him out of nowhere.

Since none of the test pilots had ever started a dogfight, his first reaction was surprise. He immediately whipped his jet around and pulled up in a vertical climb. Not completely comfortable with the controls, Yeager stalled, going straight up, and was soon spinning down, while the P-38 was spinning up. As the two passed each other, less than 10 feet apart, both planes were out of control.

“Those eyes of his were bigger than a stripper’s knockers!” recalled Bob Hoover years later. “We both fell out of the sky, regained control down on the deck, engines smoking and wide open.”

On the ground, Yeager and 1st Lt. Bob Hoover complimented each other’s flying abilities. Hoover commented that he didn’t know a P-59 “could swap ends like that!”

“I didn’t either, ’til I tried it,” was Yeager’s response.

Like his new friend, Hoover had been a combat pilot and had been shot down during the war. Unlike Yeager, the Spitfire pilot hadn’t evaded capture. He had spent 18 months in Stalag 1, before escaping, stealing a Focke-Wulf from a deserted airfield, and flying to safety and freedom. Now, he was assigned to the fighter test section. From then on, the two would dogfight whenever they could.

“Neither of us ever won,” said Hoover, who has often referred to Yeager as “the greatest dogfighter” he’s ever seen.

In the fall of 1945, Hoover and Yeager began putting on military airplane demonstrations together at local airports. Yeager knew that Colonel Boyd was impressed with him when he ordered him to stage an air show with a Shooting Star for the open house at Wright Field in early November 1945. A few days later, Boyd asked Yeager if he wanted to attend the Flight Performance School at Wright Field.

“The old man had noticed that I flew a hell of a lot sharper then his test pilots did, because I was a combat guy,” he said. “I said, ‘I only have a high school education.’ He said, ‘You shouldn’t have any problems.'”

Boyd was also very aware of Yeager’s maintenance background.

The X-1 Project

Yeager entered test pilot school in January 1946. His fellow students would include Hoover and Jack Ridley, a bomber pilot and brilliant engineer who was a huge help to Yeager. The academics were challenging, but Ridley explained the complex rules of mathematics and physics in a way that Yeager could understand.

“Jack was a really tremendous guy,” Yeager said. “He was about five years older than I was. He had a master’s degree out of Caltech in Los Angeles under Dr. von Karman (the great Hungarian aerodynamicist). Jack was one of his prized students. He was a very good pilot as well as being very good in aerodynamics.”

Shortly after graduation, Yeager reached .82 Mach in a P-84 Thunderjet, a new single-seater capable of nuclear bomb delivery. Flying straight and level at that point, the aircraft began to shake violently, while its nose pitched up. Yeager said he got the message and eased back on the throttle. As he did, he wondered if there might not be some truth to the theory of a “wall out there.”

At that time, said Yeager, all of the major aircraft companies were competing to design more powerful engines and aerodynamically sleeker aircraft “that would push us right up against that barrier in the sky.”

In explaining the “sound barrier,” which many described as a “brick wall in the sky,” Yeager says that while diving at more than 500 mph in combat, his Mustang would begin to shake violently and his controls would freeze.

“I nearly bent that damned stick straining to pull out,” he said. “I was lucky that Mustangs were slightly more resistant than the German airplanes to shock waves that form at the speed of sound.”

Air travels faster across the top curved surface of a wing than across the flat bottom, producing lift. In a steep dive, said Yeager, turbulent air ripped past his wings at 700 mph or better, while shock waves slammed against the ailerons and stabilizer. This buffeting in power dives, or compressibility, led to the widely held belief that “the laws of nature would punch the ticket for anyone caught speeding above Mach 1.”

“A lot of engineer brains thought that,” Yeager recalled. “No one knew whether there was an ‘ultimate speed’ beyond which the plane would disintegrate. It’s very difficult for people to understand what the sound barrier was, and what it was like back in 1947 or before.”

At sea level, the speed of sound is about 761 miles per hour. At 20,000 feet, the speed of sound is 660 mph. During WWII, the German Me 163 Komet rocket plane flew nearly 600 mph. Later, the British Gloster Meteor jet surpassed that speed. But in 1947, no one had yet flown faster than Mach 1. So no one knew if breaking the “sound barrier,” an “invisible wall of air,” would smash any airplane that tried to pierce it at Mach 1.

When the military gave Bell Aircraft Company a contract to design the XS-1 (X for research, S for supersonic, 1 for first), later simply to be known as the X-1, the design included a fuselage that was shaped like a 50-caliber bullet.

“Obviously, bullets go faster than sound,” Yeager said.

Twice during trips to Muroc to ferry planes back to Wright, Yeager saw the X-1, shackled beneath a B-29 bomber prior to take off. The tiny vessel was rocket-propelled, with 6,000 pounds of thrust, and designed to fly at twice the speed of sound. Four powerful rocket engines powered the small plane, built to withstand 18 times the force of gravity. Since Muroc Air Base offered good weather year-round and hundreds of miles of desert and dry lakebeds for perfect runways, it was the perfect place for testing the X-1.

“The X-1 had been flying a whole year before I graduated from the test pilot school,” Yeager said.

At that time, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, a high-powered team of scientists and engineers that was the forerunner of NASA, had the charter for research flying.

“Military guys were never allowed to do that,” Yeager said. “We did stabilitating control work or performance work. The civilian test pilots got big bonus money (known as risk bonuses).”

But Yeager and others would have a chance to fly the X-1. The pilot flying the aircraft was a sharp-looking civilian named Chalmers “Slick” Goodlin.

“Slick had flown the X-1 for a whole year, 20 powered flights, and only took it out to .8 Mach,” Yeager said.

After achieving .8 Mach, Goodlin renegotiated his contract.

“He thought things were getting too thrilling,” said Yeager. “Phase two was to take it on out to 1.01 Mach, supersonic, and he wanted 150,000 bucks, which was a lot of money in ’47. Had he gone on and broken the sound barrier with the X-1, he could have made millions, because he was a civilian! The Air Force said, ‘This is bullshit! We have pilots that are a helluva lot better than these civilian pilots. Let’s take the airplane over and assign Air Force test pilots or Air Corps test pilots, and let them do the work.’ We got a lot of resistance, even in the headquarters—congressional pressure. NACA was lobbying a lot to try to keep that mission of research flying.”

It was Boyd’s responsibility to select two pilots out of more than 100. When they asked for volunteers in May 1947, Yeager and Hoover, two of the most junior test pilots, as well as Ridley and a handful of others threw their name in the hat.

A few days after Yeager volunteered, Boyd sent for him, telling him that the mission was extremely risky. He also that that it was the military’s first crack at being allowed to conduct research flying, and that they weren’t going to blow it, like the British. He was referring to early 1947, when during a practice dive in his attempt to break the sound barrier, Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. perished when his experimental aircraft, The Swallow, a semi-tailless airplane, disintegrated at .94 Mach.

Then, Boyd asked Yeager whom he would choose for his backup pilot and flight engineer, if he were selected.

“I told him I’d pick Hoover as backup because he was a fabulous stick-and-rudder man, and Jack Ridley as flight engineer, because he was one helluva brain and a good pilot, too,” he said.

In a 1976 interview taped shortly before his death, Maj. Gen. Albert G. Boyd said that selecting the X-1 pilot was one of the most difficult decisions of his life.

“If the pilot had an accident, he could set the program back a couple of years,” he said.

Although Yeager, 24, was married and had children at the time, and Boyd had first thought he needed to select a bachelor, for obvious reasons, there was no doubt that Yeager was “the one,” due to his ability to perform, his stability and willingness to follow instructions, and, of course, his tremendous ability as a pilot.

Boyd later said that Yeager was the best “instinctive” pilot he had ever seen. He added that he had demonstrated an “extraordinary capacity to remain calm and focused in stressful situations” and had “a willingness to follow instructions.” Certainly, his maintenance background was invaluable.

“The X-1 was a very complex airplane, so he knew that I had better watch out what I was doing or the damned airplane would blow up and kill me real quick,” Yeager said.

And, Boyd was confident that Ridley, providing the engineering backup for Yeager, would be incredibly useful. Hoover was assigned as Yeager’s backup pilot.

The decision Boyd made wasn’t popular with many of their fellow test pilots, and didn’t thrill NACA either. Besides the issue of education, or the lack thereof, Yeager said there were other matters as well.

“Jack was a captain, I was a captain and Hoover was a first lieutenant,” Yeager said. “They looked at us like dog bait—a bunch of raunchy military guys. And the professional test pilots didn’t very well like Hoover and me, because we used to wax their tail every day they’d take off. We’d jump them, and we were good, because we were combat pilots. It’s a different kind of flying, so we would just wax them, whenever.”

Still, Yeager said, people tended to listen to Ridley.

The X-1 team included, from left, flight engineer Ed Swindell, backup pilot Bob Hoover, B-29 pilot Bob Cardinas, pilot Chuck Yeager, Bell engineer Dick Frost and Air Force engineer Jack Ridley.

“When ole Ridley opened his mouth to talk, those NACA guys learned to shut up and listen, because he knew exactly what he was talking about,” he said.

Getting Through The Barrier

Boyd’s biggest concern was whether the structural integrity of the X-1 could withstand the extreme stress loads likely to be encountered at Mach 1. Yeager would be flying higher—around 45,000 feet—and faster than any military pilot had yet flown.

The Air Corps medical labs decided that Hoover and Yeager would be perfect specimens for experiments to learn about the limits of human endurance under maximum G loads and extreme high altitude. The two pilots were now the first Air Corps “research pilots”—fair game for all the torture that the astronauts would later suffer.

In the spring of 1947, Yeager and Hoover were strapped onto centrifuges and locked into altitude test chambers, to test different kinds of “primitive” pressure suits. As experienced fighter pilots, they could routinely withstand the pull of four Gs without any G suits.

“They put tremendous loads on us, while strapped standing up and lying down,” said Yeager. “It was miserable, and we got sick as dogs.”

David Clark, a corset manufacturer in Worcester, Mass., received an Air Corps contract for the first high-altitude pressure suits. Yeager and Hoover flew there in a B-25 bomber to be outfitted. Yeager said the first models were so cumbersome that they looked like Pillsbury doughboys.

“There was no way we could eject from an airplane wearing them,” he said.

The X-1, only 31 feet long with a 28-foot wingspan, had a high tail with a stabilizer in the fin, well above the wake of turbulent air off the wings at transonic speeds. Its straight, extremely thin wing delayed the onset of shock waves as long as possible. Although it was a beautiful airplane to fly, many thought it was doomed. NACA was in charge of the 500 pounds of monitoring instrumentation aboard the X-1.

“They ultimately had a lot to say about the pace of our flights—how quickly we attempted to breach the barrier,” said Yeager.

Yeager admits that the “orange beast” intimidated him. Because of that, he decided to ask advice from someone who knew it intimately. After he and the rest of the small X-1 test team met at Muroc in late July 1947, he enlisted the help of Florence “Pancho” Barnes, who ran the Fly Inn Bar and Restaurant—later to be known as the Happy Bottom Riding Club—at the edge of Rogers Dry Lake. Barnes thought it was wonderful that her good friend was flying the X-1 “for the kick of flying it, and not for some big contract bonus.” That was just one of the reasons she never let Yeager pay for food or drinks.

“At Pancho’s, they were all rich and drove big cars,” Yeager said. “Here’s a captain with a wife and two kids, and $260 a month. Pancho would say, ‘You drink and eat what you want, and don’t pay a cent. She charged those damn civilian pilots double!”

When Yeager decided it might be worthwhile asking Goodlin for tips, Pancho set up a dinner where they could talk.

“I asked him for a few pointers on landing patterns, because you’re dead-sticking the airplane in,” recalled Yeager. “He said, ‘Well, if the Air Force wants to draw up a contract for a thousand dollars, I’ll talk to you.’ I said, ‘If you can fly it, I can fly it, too.’ I just got up and walked away. Civilian test pilots are that way.'”

Yeager recalled that just before the first flights in the X-1, Gene May, another civilian test pilot, asked him and Hoover why they thought they could fly faster than sound.

“Well, Mr. May, Captain Yeager and I happen to have more time flying jets than you or any other 10 civilian fliers you can name, so, what makes you think we can’t?” Yeager recalled Hoover saying.

Then, Pancho jumped into the conversation.

“That’s right, Gene, these two can fly right up your ass and tickle your right eyeball, and you would never know why you were farting shock waves,” Yeager remembered.

“That gal had a heart of gold,” he said. “She was a helluva good pilot back in the Tom Thumb days in the ’30s, with Amelia Earhart and Jackie Cochran.”

First Flights

The X-1 sported the name of Yeager’s wife, but this time as Glamorous Glennis.

“The Air Force didn’t take kindly to having her name on the X-1, because you didn’t do that in the war,” Yeager said. “I thought, ‘Hell, I’m the only one flying it; it’s my airplane.’ But it really wasn’t my airplane. They backed off a little bit. I don’t think they wanted to piss me off.”

The first non-powered, familiarization flights were scheduled for the middle of August. The X-1 didn’t take off like a conventional aircraft. Yeager would be dropped at 25,000 feet from the B-29 mother ship, without fuel, and glide back down and land on the lakebed.

The morning of the first flight, he watched them load the X-1 under the B-29. After boarding the mother ship, Yeager would sit behind Maj. Bob Cardenas, the pilot, and Ridley, the copilot, as they taxied out and took off. Cardenas kept his climb within gliding distance of Rogers Dry Lake. His flight plan called for him to climb to 25,000 feet, and then back off for about 40 miles to pick up speed. He dropped the nose into a 20-degree diving angle until he reached 240 mph indicated. Then, he gave Yeager a countdown of 10, and dropped him.

At 12,000 feet, Yeager headed for the ladder, and slid into the X-1 feet first. Ridley followed him down the ladder and held the door in place while Yeager locked it from the inside. In the darkness, Yeager put on his helmet and oxygen mask, and hooked into the communications systems.

Dick Frost, Bell’s X-1 project engineer, flew low chase, and Hoover flew high chase. On Yeager’s first flight, as he was going over his checklist, Hoover couldn’t resist buzzing him. He flew by so close that he almost knocked Yeager loose from the B-29.

“You bastard!” said Yeager, as he rocked and swayed.

“I was really hot,” he recalled. “I said, ‘If this thing carried guns, I’d shoot your ass out of the sky.'”

He recalled Hoover laughing and saying, “Come and get me.”

“Well, I didn’t try on this first glide flight,” Yeager said. “But on the third, when I saw him turning toward me, I turned into him and we had a dogfight down to the deck, just like at Wright, only this time I almost stalled the damned X-1 waxing Bob’s fanny true and good.”

Powered Flight

Yeager said the “big boy” flights were next. On the morning of the first powered flight, Aug. 29, 1947, the base was closed until the project was safely off the ground. The X-1, carrying 600 gallons of liquid oxygen and water alcohol, was extremely volatile.

Yeager and Ridley had already talked it over and agreed that since Goodlin had taken the X-1 to .8 Mach, they would start by going out to .82 Mach. Boyd approved, but made the condition that they go up in increments of 15 or 20 mph on each flight.

At 25,000 feet, the B-29 nosed over and started its shallow dive. When he released, Yeager was jolted from his seat as he sailed out of the bomb bay. He was supposed to be dropped level, but the dive was too slow, and they dropped him in a nose-up stall.

As the nose went down, he picked up speed, and leveled out about a thousand feet below the mother ship. As he lit the first chamber, Yeager was slammed back in his seat. Then, the nose went up. He turned off the rocket chamber, lit another, and was soon streaking up at .7 Mach. At 45,000 feet, he turned on the last chamber.

The flight plan called for him to jettison remaining fuel and glide down to land. He did turn off the engine, but instead of jettisoning the fuel, he rolled over and dove for Muroc. While reading .8 Mach, his dive-glide was faster than most jets at full power. Once the fuel was gone, he was traveling at .85 Mach, at 35,000 feet.

Yeager said that going out to .85 Mach that soon put the program out on a limb because it carried them beyond the limits of what was known about high-speed aerodynamics into the unknown.

“Ridley and I called it ‘the Ughknown,” said Yeager. “We knew absolutely nothing, because no airplane had ever been above 85 percent of the speed of sound. There was no wind tunnel data, so when we got up at about .9 Mach, we were in uncharted territory. We had no help. NACA was running the instrumentation; they wouldn’t give us the time of day, because they were kind of mad that we crummy military pilots were doing research flying for them.”

Yeager said that although it was an Air Corps research project, the 17 NACA engineers and technicians wanted to control the missions. Although Yeager wanted to be careful, he also wanted to “get it over with.” Boyd’s decision was to go up only two-hundredths of a Mach on each consecutive flight.

On October 5, when he made his sixth powered flight, Yeager experienced shock-wave buffeting for the first time at .86 Mach. When he increased his speed to .88 Mach, he saw his aileron vibrating with shock waves, but, with effort, could hold his wing level.

On his seventh flight, while flying at .94 Mach at 40,000 feet, Yeager experienced the usual buffeting, but when he pulled back on the control wheel, nothing happened. The airplane continued flying with the same attitude and in the same direction.

“The control wheel felt as if the cables had snapped,” he said. “I didn’t know what in hell was happening. I turned off the engine and slowed down. I jettisoned my fuel and landed feeling certain that I had taken my last ride in the X-1.”

Yeager told Ridley he thought there was no way he was going faster than .94 Mach without an elevator.

“We called Col. Boyd at Wright, and he flew out immediately to confer with us,” Yeager said.

NACA analyzed the telemetry data from the flight, and said the reason they lost the elevator effectiveness was that a shock wave formed on the horizontal stabilizer.

“It formed at about .88 Mach,” Yeager said. “As our speed increased to about .94, that shock wave laid down and moved back on the horizontal stabilizer until it was at the hinge point of the elevator. The elevator lost its effectiveness, so we had no control of the airplane.”

Yeager credits Ridley for saving the day. After giving some thought to what had happened, he suggested it might be possible for Yeager to fly without using the elevator, by using only the horizontal stabilizer.

Because they had anticipated elevator ineffectiveness caused by shock waves, Bell’s engineers had built an extra control authority into the stabilizer. Basically, said Yeager, Bell had built in the capability to change the angle of incidence, or the angle of the horizontal stabilizer. The extra authority, a trim switch in the cockpit, would allow a small air motor to pivot the stabilizer up or down, creating a “moving tail” that could act as an auxiliary elevator by lowering or raising the airplane’s nose.

“It maintained its effectiveness,” said Yeager. “Basically, we found out that if my airplane started to pitch up, I had to use a horizontal stabilizer to control it.”

On the following flight, the stabilizer system provided just enough control that Yeager and Ridley both felt Yeager could get by without using the airplane’s elevator. Yeager let the airplane accelerate up to .85 Mach before testing the trim switch. When everything went well, he climbed and accelerated up to .9 Mach, then .94 Mach, where he had lost his elevator effectiveness. He made the same trim change, again raising the nose, just as he had done at the lower Mach numbers.

Everything seemed to be fine, but when Yeager was about to turn off the engine and begin jettisoning the remaining fuel, the windshield began to frost.

Because of the intense cabin cold, fogging was a continual problem, but he was usually able to wipe it away. This time, a solid layer of frost quickly formed. Yeager radioed Dick Frost, flying low chase, and told him the problem. Frost talked him in. Rogers Dry Lake gave him an eight-mile runway, but that didn’t make the landing “untricky.” Between the two of them, he said, they made the landing look deceptively easy.

Before his next flight, Jack Russell, his crew chief, applied a coating of shampoo to the windshield, which worked as an effective anti-frost device. With Boyd’s approval to press on, Yeager looked forward to the next flight.

“We sat down with the NACA team to discuss a flight plan,” he said. “I had gone up to .955 Mach, and they suggested a speed of .97 Mach for the next mission.

What they didn’t know until the flight data was analyzed several days later was that Yeager had actually flown .988 Mach while testing the stabilizer.

“In fact, there was a fairly good possibility that I had attained supersonic speed,” said Yeager.

That Sunday, Chuck and Glennis Yeager went to Barnes’ for dinner. After dinner, they rode horses for about an hour, before deciding to race back in the moonless night. Unfortunately, Yeager, slightly in the lead, couldn’t see that someone had closed the gate until he was practically on top of it. When he tried to veer his horse to miss it, it was too late, and he hit the gate and tumbled through the air, landing so hard he was knocked out.

He feared that what felt like a spear in his side was a broken rib, but he didn’t want to go to a base hospital to confirm that. If that was the case, most likely the flight surgeon would ground him. He wasn’t about to let that happen.

Chuck Yeager—Breaking the Sound Barrier (Part 2)