By Di Freeze

Finale

Chuck Yeager was in immense pain when he visited a local doctor in Rosemond. He confirmed Yeager had two cracked ribs. He taped them, and told Yeager to take it easy.

The pain was now at least manageable, and Yeager was able to drive himself to the base that afternoon. There, Yeager told Ridley what had happened, and Ridley set to work finding a solution.

Yeager drove with an H-shaped control wheel on which the rocket thrusters and key instrumentation switches were located. Since he didn’t have to move his hands at critical moments, and knew every move he had to make, he knew he could fly with broken ribs. But, how was he going to be able to lock the cockpit door, which took some lifting and shoving? Ridley came up with the idea of using a 10-inch piece of broomstick to use to raise the door handle to lock it. When they tried it, it worked.

On Oct. 14, 1947, at 6 a.m., Glennis drove Yeager to the base. On this, his ninth flight, the plan called for him to reach .97 Mach.

Cardenas dropped the X-1 at 20,000 feet, but his dive speed was once again too slow, and the X-1 started to stall.

“I fought it with the control wheel for about 500 feet, and finally got her nose down,” Yeager said. “The moment we picked up speed, I fired all four rocket chambers in rapid sequence.”

Yeager continued to climb. As expected, the X-1 encountered buffeting at .88 Mach, but when Chuck Yeager flipped the stabilizer switch, and changed the setting two degrees, things smoothed out. At 36,000 feet, he turned off two rocket chambers. He reached an indicated Mach number of 0.92 as he leveled out at 42,000 feet and relit a third chamber of his engine.

The X-1 rapidly accelerated. Yeager noted when the meter reached .965, and then was surprised to see it fluctuate off the scale. As soon as that happened, he radioed Ridley. They were quickly interrupted by someone in the NACA tracking van reporting they had heard what sounded like a distant rumble of thunder. It was Yeager’s sonic boom. Yeager had flown for 18 seconds at supersonic speeds.

“We smoked it out to 1.07,” he said. “I was surprised. There had been such a tremendous amount of anxiety about what the hell would really happen to the airplane at the speed of sound. But all the buffeting quit and the airplane flew very smooth. Nothing happened.”

After all the anticipation and consternation, after the jokes about the “Ughknown,” breaking the sound barrier was more like a “poke through Jell-O.”

That day, as usual, fire trucks raced out to where the X-1 had rolled to a stop on the lakebed. Then, Yeager hitched a ride back to the hangar with the fire chief, where Glennis, who had no idea what had happened, was waiting. After he had climbed in the car, saying simply that he was beat, Frost and Hoover ran up and began clapping Yeager on the back.

Frost instantly nixed the idea of Yeager heading home. Instead, they went to the operations office, to call Bell and Boyd with the news. Then, it was on to the officers’ club to eat, drink a toast and plan a big party for that evening at Pancho’s.

In the midst of the celebration, a call came in from Boyd’s office informing them that the flight was not to be discussed. In light of the new orders, the men headed instead to Yeagers’ house, about 35 miles away, and then on to Frost’s, where they continued celebrating in private.

It would be eight months before the public would hear about the breaking of the sound barrier.

Yeager, among others, felt the historic flight should have received recognition sooner than it did. About a week after the flight, he was flown back to Wright for a top-secret ceremony in the commanding general’s office, where he received another Distinguished Flying Cross.

Although hushed from the public, Washington knew what was going on and wanted to meet the pilot. That alarmed some. Col. Fred Ascani, Boyd’s executive officer in Flight Test in 1947, later recalled that Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg, who was “very Ivy League,” instructed Wright to “keep that damned hillbilly Yeager out of Washington.”

It was planned that Yeager would continue flying the X-1 until they had exhausted its research capabilities. He assumed that since he’d reached Mach 1, the remainder of the X-1 flights would be downhill. However, that wasn’t the case. Besides other difficulties, in early 1948, Yeager flew several flights where each time he started an engine, the fire warning light would flash, and the cabin would fill with smoke. That problem was eventually solved when a Bell engine designer discovered the wrong gaskets had been installed during overhaul.

After his 23rd powered flight in the X-1, during which none of the engines ignited, Boyd ordered him to take a break, and Yeager didn’t argue.

The News Is Finally Out

In December 1947, Aviation Week leaked the news of the sound barrier flight, but the Air Force didn’t confirm it until the following June.

When Yeager’s achievement was finally declassified, he quickly became known as “the Fastest Man Alive.” To mark the occasion, he was awarded the Collier Trophy, one of the most prestigious honors in aviation, for “an epochal achievement in the history of world aviation” which, according to the presenter, was “the greatest since the first successful flight of the original Wright brothers’ airplane, 45 years ago.”

His growing fame meant he was in demand as a speaker. But when a colonel at the Pentagon told him he was to begin a round of personal appearances, Yeager told him he didn’t do speeches—he was a fighter pilot. However, the orders came directly from the Chief of Staff’s office, which thought it would be great public relations for the Air Force.

Yeager said the public really didn’t understand the concept of the sound barrier, and that the press’ description of “a brick wall in the sky” made him seem like a young Captain Marvel.

“The Air Force insisted on putting me up on a pedestal, and there was no lack of volunteers trying to knock me down,” said Yeager. “A few of them came damned close to wrecking my career.”

Yeager was famous, but that didn’t change his quality of life out on the desert.

“When I was sent out to Muroc, I was TDY (temporary duty) from Wright Field,” he said. “Since I was going to be out there for the next two or three years, I brought Glennis and my kids out. Glennis wasn’t allowed to visit the hospital with the kids; she wasn’t allowed in the commissary or PX, and there was no housing on the base. We lived in chicken shacks all over that damn desert. That’s the way the system was. I didn’t pay much attention to it, because I was doing my job, and that was it. But it was tough on Glennis.

“Basically, when I brought her out, she knew I was so close to the raggedy edge of fatal programs that anything that detracted from my concentration would kill me. She took it upon herself, which was very unusual for an Air Force wife, to do everything that she could to keep me from breaking my concentration on my flying. I was so close to the ragged edge during those years that had anything detracted from me, I would have ended up in a smokin’ hole. But, that’s the way she was; she was a helluva good wife.”

Edwards Air Force Base

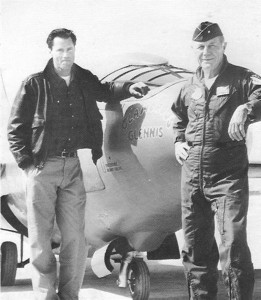

Muroc Air Base was re-designated Edwards Air Force Base in 1949, in honor of Captain Glen W. Edwards, who died while copiloting the Northrop YB-49, the all-jet version of the Flying Wing bomber prototype. In the meantime, Yeager continued testing the X-1, as well as different aircraft.

“I was working on 10 different test programs, with the X-1,” he said. “In 1951, in one month alone, I flew 27 different kinds of airplanes. It was a busy time. I was working on the X-3, X-4, X-5, plus all new airplanes like the F-86 and the F-84F and F-100s.”

In 1949, even though the X-1 was designed to be dropped from a mother ship, Yeager make a ground takeoff in it.

“Just to screw the Navy,” he said. “They had a swept-wing D-558 Skystreak. The Navy was running it; Douglas Aircraft built it. I wasn’t particularly fond of either one of them. They were putting out publicity in the newspapers and aviation magazines that the X-1 had to be dropped from a bomber, so it wasn’t ‘really’ a true supersonic airplane, but that this D-558 was. Well, the day before they flew the D-558 for the first time, Ridley and I rigged up the X-1 and put a hundred seconds of fuel in it—a minute and a half instead of two and half—and made a ground takeoff. We did an Immelman and rolled out 23,000 feet at 1.03 Mach, and we had all the press up there. The Navy got really pissed at us. That was just the way we were—very competitive, and we were very proud of the Air Force.”

In late September and early October 1953, at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Yeager and Maj. Tom Collins tested the first Russian MiG-15 that fell into American hands. Two months later, he had broken Mach 2, but not without quite a bit of excitement.

“We were coming up on the 50th anniversary of the Wright brothers’ first flight,” Yeager said. “Scott Crossfield had been up to Mach 2 in the D-558, and then taken all of the damn news media. So, the 12th, four days before the anniversary of the Wright Brothers, I took the X-1A out. I tell you, the news media were scrambling. We hadn’t said a word until December 17th, and really caught them flat-footed.”

During that flight, Yeager experienced buffeting at .95 Mach, and soon realized he was climbing too steeply.

“The sun glaring off my helmet visor made it impossible to see my flight attitude indicator,” he recalled. “Instead of a 45-degree climbing angle, I was going up at 55 degrees.”

To correct it, he lowered the X-1A’s nose, and was soon going through 60,000 at 1.1 Mach.

“By the time I reached the top of the arc and began to level off, I could’ve shaken hands with Lord Jesus,” he said.

Yeager was nearing flameout when he hit Mach 2. When the Mach meter showed 2.4, the nose began to yaw left. When Yeager tried to correct it, the X-1A rolled sharply to the right, snapped to the left, and then tumbled violently out of control. He had become the first pilot to encounter inertia coupling. Later, Boyd said he didn’t know of another pilot who could’ve walked away from that incident.

“In less than a minute, he’s back in control and cracking a joke about not having to run a structural demonstration on this airplane,” he recalled.

When referring to that incident, and others that were as tense, Yeager says he doesn’t call them “close calls.”

“You don’t look at them that way,” Yeager said. “Number one, either you do or you don’t. Nothing is close. You don’t have to say, ‘Well, man that was close.’ Bull! It wasn’t close if you survived. It was close if you got killed.”

General Eisenhower presented Yeager with the Harmon Trophy at the White House in the spring of 1954 for that flight. Yeager’s speed record stood for nearly three years until Bell’s X-2 began its flights at Edwards and cracked Mach 3.

The F-100 Super Sabre

Although Yeager wasn’t particularly impressed with civilian test pilots, there were a few he thought were good.

“Guys like Tony LeVier and Fish Salmon were quite good,” he said. “I liked them. Before they flew a new airplane, they’d ask me to chase them because I knew what the hell they were doing better than they did. They were nice guys, but there were some that were real jerks.”

After civilians flew a preliminary test to insure a new airplane’s airworthiness, Air Force test pilots verified their data to determine whether aircraft met military specifications.

“As soon as I got my hands on a new airplane in that first phase, I did everything to it that could be done,” Yeager said. “I’d spin and dive test it because I enjoyed the challenge. When the manufacturers saw my data cards, they’d call in their own pilots and ask, ‘Why should we pay you for a spin test when Yeager already did it?’ One time, Tony LeVier, the Lockheed test pilot, said, ‘You sumbitch! I had about a $25,000 bonus to do the spin test on the 104 and here you go and do the flight test!”

In 1953, Yeager flew North American’s F-100 Super Sabre.

“It was the first airplane that would go supersonic straight and level,” Yeager said. “Pete Everest and I flew the airplane as military test pilots. We said, ‘Hey, this airplane is directionally unstable; the flight control system isn’t worth a damn.’ Wheaties Welch and all the other test pilots at North American said, ‘You guys are too critical.’ They were going to bring the non-test pilots in from Pat, just typical fighter pilots, and say, ‘Here, fly the airplane.’

“Hell, all these guys could see was 1.1 Mach, straight level, and they said, ‘Man, this is really great!’ They didn’t fly in formation and they didn’t know anything about stability. The Air Force went ahead and bought 200 of the airplanes before they started really creaming them.”

Welch died in September 1954, while diving an F-100 at 1.4 Mach.

“They went back to North American and said, ‘You take these airplanes back, and you put a bigger tail on it and a nonlinear stick to stabilize the flight control system.’ North American lost a hell of a lot of money on that,” Yeager said. “Had they listened to us, they wouldn’t have had a problem, but they listened to their civilian test pilots.”

By the summer of 1954, Yeager was test-flying Lockheed’s F-104 Starfighter, the “missile with a man,” which flew at Mach 2 and climbed more than 10,000 feet a minute. Besides other aircraft, over a six-month-period, he also tested the nation’s biggest new bomber, the prototype of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, the nation’s first swept-wing, six-engine bomber. He did stability and control tests on the Stratojet, and when it became operational a year later, Strategic Air Command asked him to train fuel tanker operators in airborne refueling.

In the fall of 1954, Yeager found out that he would be returning to operational flying. He was taking command of the 417th Fighter Bomber Squadron, a component of the 50th Fighter Bomber Wing, commanded by Col. Fred Ascani.

Jackie Cochran

In “Yeager,” Glennis Yeager recalled that Jacqueline Cochran and Pancho Barnes had several things in common, including both wishing they were men and living vicariously through her husband’s accomplishments. Also, neither wanted anything to do with other women, especially each other, going back to their early women’s air racing days.

Because of that friction, it was a wonder when they were in the same room together. Yeager managed to pull off that feat shortly before he left Edwards for Hahn Air Base in Germany. The occasion was a party given for him.

“I had Glennis with me on one side, Pancho on the other side and Jackie on the other side of Glennis,” he said. “I tell you, you’re between two wild cats!”

Yeager and rags-to-riches aviatrix Jacqueline Cochran experienced several adventures together.

“She was one helluva good pilot,” he said. “In her F-86, T-38 and F-104 record setting, she did a lot better than a lot of men test pilots that I knew.”

Yeager recalled a time shortly after meeting her when she invited him to have lunch with her.

“Jackie took me into this dining room that’s for four-star generals; she goes right through, took the secretary’s table and just sat down,” he said. “I sat down, and all these damn four-star generals were looking at me, a little captain. I said, ‘Man, how to get fired real quick!'”

Yeager said Cochran didn’t talk much about her childhood, but he knew that she never knew her real parents or why they gave her away, and that she grew up in poverty.

“Compared to what she suffered as a child in rural Florida, I was raised like a little country gentleman,” he said.

Professionally cutting hair by 13, Cochran also attended nursing school, before returning to her career as a beautician, which led to Antoine’s in New York’s Saks Fifth Avenue, and the idea of starting her own line of cosmetics. In 1932, she met millionaire financier Floyd Bostwick Odlum at a dinner party. Cochran wanted to launch a cosmetic firm. Her future husband—whose business empire included ownership of General Dynamics, the Atlas Corporation and RKO—told her that to cover the most territory, she would need to learn to fly.

In obtaining her pilot’s license, Cochran discovered her life’s passion. Her history before meeting Yeager included becoming the first woman to enter and win the Bendix Transcontinental Race and serving as director of the Women Airforce Service Pilots.

Yeager and Cochran met for the first time in 1947, shortly after he broke the sound barrier.

“We liked each other right off the bat,” he said.

He quickly realized that Cochran was “used to getting her own way.”

“She was a steamroller,” he said.

In 1953, when Yeager was preparing for his flights in the X-IA, Cochran approached General Vandenberg about trying to set speed records in an F-86. She used a Canadian-built Sabre. Since she was a civilian, she needed special permission to use Air Force facilities and equipment.

During a trip out to Edwards, Vandenberg discussed her request with Gen. Boyd, before approving her request. Col. Ascani, who then owned the existing low-altitude speed record, was asked to make all the arrangements.

Cochran had no jet experience, so Yeager gave her about a half-dozen orientation flights.

“After six or so flights in the Sabre, I figured she knew it well enough, so I took her up to 45,000 feet and told her to push her nose straight down,” he recalled. “We dove together, wing to wing, kept it wide open and made a tremendous sonic boom above Edwards. She became the first woman to fly faster than sound. She loved to brag that she and I were the first and probably the last man and woman team to break Mach 1 together.”

Later, she set new speed records in the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, a Mach 2 airplane.

Operational Flying

From Yeager’s point of view, being back with a fighter squadron was “like coming home to the hollers of West Virginia.” He was back among his own kind, who talked his language.

In “Yeager,” Emmett “Jock” Hatch recalled that Major Yeager, whom those under him “hero-worshipped,” made his personal mark in the squadron in several ways. That included ordering them to wear red scarves and deciding they would fly in a diamond formation, when Air Force regulations demanded that all squadrons fly in a stacked formation.

“The acrobatic teams fly a diamond, and we’re as good as they are,” Yeager said. They became “The Red Diamonds.”

Ten months after he arrived at Hahn, the wing received the F-86H Sabre, which had greater range and carried heavier loads. Their mission suddenly changed from air defense to “special weapons.” Carrying nuclear weapons (each carried one Mark XII tactical nuclear bomb), the fighter-bombers began to train in techniques for dropping them.

Since they were now a nuke squadron, in order to disperse targets of potential Soviet attack, they were moved to a make-ready strip just across the German border in Toul-Rosiere, France. Yeager was there for over a year, and commanded the best performing squadron in the wing. He left France as a light colonel with good marks as a TAC squadron commander.

Back In The States

When Yeager was offered command back in the States of the 1st Fighter Day Squadron, a squadron of F-100 Super Sabres, he quickly accepted it. The new assignment, which he began in April 1957, took him to George Air Force Base, just 50 miles from Edwards.

At that time, the ability to refuel without landing was “as revolutionary to military aviation as the invention of the jet.” Armed with air-to-air Sidewinder missiles, the Super Sabres refueled from airborne tankers, which was a first for Tactical Air Command.

In World War II, it had taken a full six months to transport and establish an operational fighter squadron in England. Now, they could fly anywhere and set up for combat in a matter of days.

In 1958, Yeager planned and led the first flawless transatlantic deployment of a jet fighter squadron in TAC history, when all of the 1st’s F-100s landed together and on schedule at Moron Air Base, Spain. The unit repeated the feat when it redeployed back to George AFB four months later.

A Big Party In Aviano, Italy

In the winter of 1959, Yeager’s squadron of 18 Super Sabres deployed from the States back to Spain, then on to Aviano, Italy. During their first weekend there, Col. Pete Everest flew up from North Africa, and Yeager threw a squadron party in his honor.

Later, while driving to a restaurant in a staff car, down narrow, winding streets, they managed to break a headlight and dent a fender. They got back to the club around 11, and the party was still in full swing.

“The guys who were still standing were outnumbered by the guys who weren’t,” Yeager recalled. “The jukebox was turned over and some wine bottles were broken.”

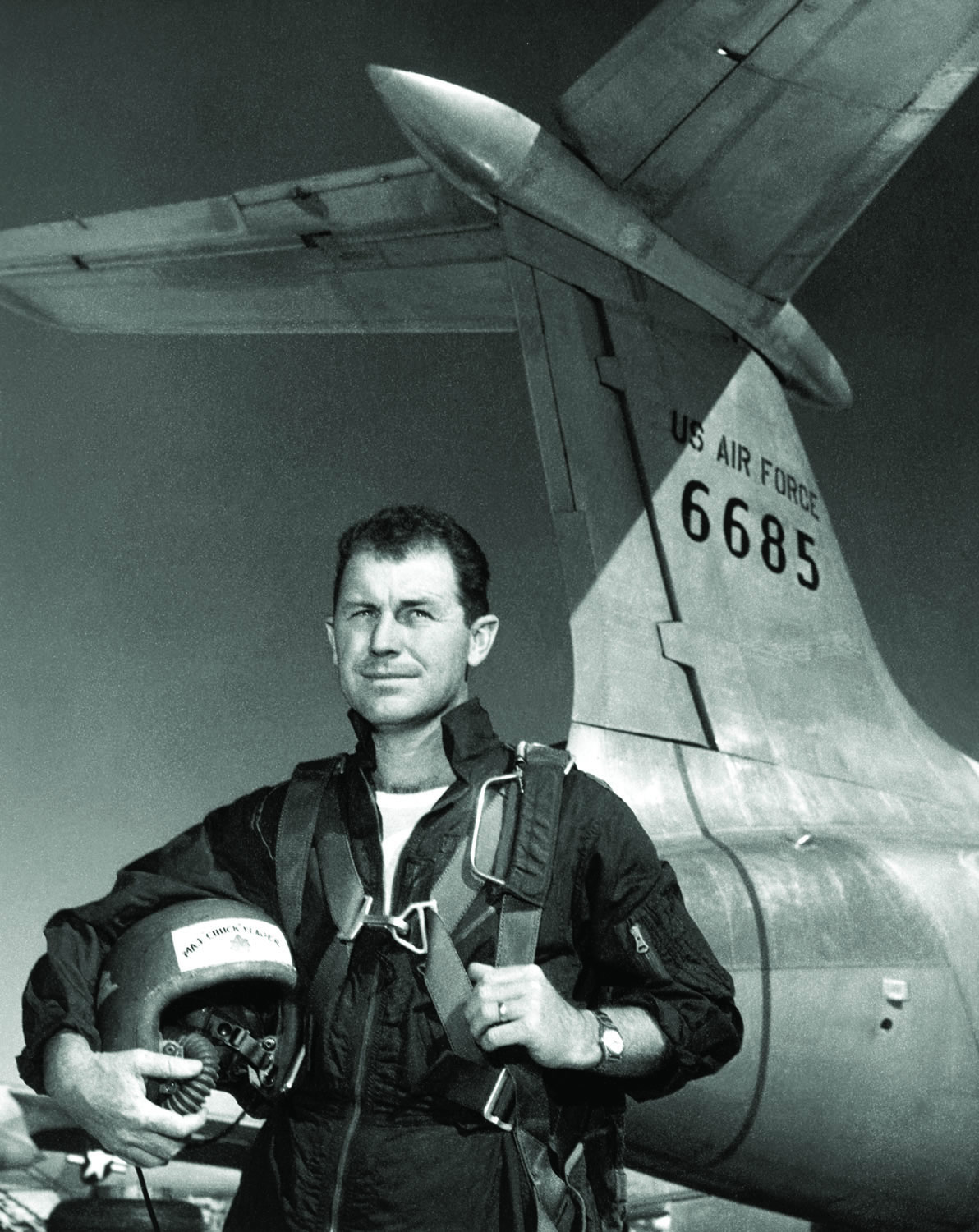

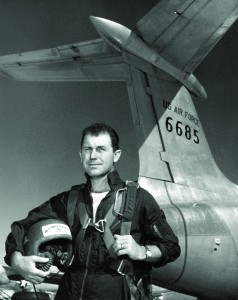

Retired Brig. Gen. Chuck Yeager salutes Maj. Gen. Doug Pearson, commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards, after stepping from an F-15 Eagle on Oct. 26, 2002, at the Edwards Open House and Airshow.

Yeager paid the club manager for the damage, and went to sleep. The next morning, he found out that the base commander, which he’d already had a confrontation with, had called his superior, the commanding general of the Seventeenth Air Force, to say that he wanted Yeager gone.

Then, Yeager received a wire from TAC headquarters, saying he was to assign command of his squadron to his deputy, and report to Gen. Frank F. Everest immediately. Yeager made the trip to the States fearing the worse.

Everest listened while Yeager told his side of the story. Finally, he said that he knew Yeager had done a good job with the squadron, and that he had pulled him out of Italy to save his career, since there had been talk about a court-martial. He advised Yeager to go back to George and cool his heels for the next couple of months. In 1960, Yeager attended Air War College in Montgomery, Ala., where he found out that he was still in good standing, when he made full colonel. Then, he was given his new assignment.

Commandant Yeager

Yeager, who consulted on the movie, “The Right Stuff,” released in 1983, said both the consulting and watching the movie was a lot of fun.

“The way they portrayed the Air Force, you had Air Force guys doing research to support NASA, and getting killed,” he said. “And then you had seven astronauts who had done absolutely nothing, and they had professional PR guys assigned to each one to blow them out of shape. That was pretty well portrayed right. But it was blown out of shape a little bit about the German scientists and LBJ raising hell about John Glenn’s wife and stuff like that. But I’ll tell you what; it was good entertainment!”

Yeager said that right after the bestselling book of the same name by Tom Wolfe came out in 1979, people began asking him one particular question that annoyed him. They wanted to know if he had “the right stuff,” which he feels implies that someone is “born” with the “right stuff.”

“I know that golden trout have the right stuff, and I’ve seen a few gals here and there that I’d bet had it in spades, but those words seem meaningless when used to describe a pilot’s attributes,” he said in “Yeager.”

Since “The Right Stuff” was mainly about the first astronauts, Yeager answers the question on if there was ever a question about him being one.

“No,” he says firmly. “When the program started in 1959, in order to apply for the space program, you had to have a degree. I only had a high school education, so I didn’t give it a second thought; it was an impossibility. But I was the commandant in the astronaut school before President Johnson and his administrator for NASA decided to make space for ‘peaceful purposes,’ and give space responsibility to NASA, and take the military out of it.

“They thought if they did that the Russians would not build space weapon systems. That was a stupid attitude to have. When they kicked us out, we had the X-20 Dinosaur, the Manned Orbital Laboratory—a lot of the very similar things that are in existence today. When they turned it over to NASA, the Russians moved right into the void.”

The new USAF Aerospace Research Pilots School at Edwards was tasked with training military pilots for space flight. NASA’s Mercury astronauts had been chosen before the school geared up, but over the next six years, the space agency would recruit 38 of the graduates to their corps of astronauts.

“The Air Force wasn’t interested in going to the moon,” Yeager said. “The military was interested in space weapons; so were the Russians.”

Yeager said that the U.S. had plans since 1947, for orbiting military space stations manned with our own astronauts.

“We knew damned well the Russians had similar plans; we aimed to beat them to it,” he said. “All we needed was the green light from Congress and the White House.”

The job of the school was to “train a first generation of military aerospace test pilots in the highly precise and disciplined flying demanded by orbiting space labs and transportable shuttles,” Yeager said. His staff included Frank Borman, Tom Stafford and Jim McDivitt (before they joined NASA). The first couple of classes consisted of experienced military test pilots who had graduated from Edwards’s test pilot school whose abilities and academic background were demonstrably outstanding.

Yeager and others on the selection board met several times to choose the top applicants. After several months of interviewing, the final selection committee published their list of the first 11 students out of 26, as well as four alternates.

“We only had enough money for 11 students to go through a year’s course,” Yeager explained.

Not long after that, Yeager found himself embroiled in controversy.

“The White House, Congress, and civil rights groups came at me with meat cleavers, and the only way I could save my head was to prove I wasn’t a damned bigot,” he recalled.

Shortly after the list was published, Yeager received a phone call from Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis LeMay’s office asking whether any of the first 11 were black pilots. When Yeager explained that only one black pilot, Ed Dwight, had applied for the course, and he wasn’t in the top 11, he was told it didn’t matter; they “needed” a black pilot.

“The Kennedy administration, especially Bobby Kennedy, went to the Air Force and said, ‘I want a colored guy in the space program,'” Yeager recalled. “LeMay said, ‘I have a hornet’s nest back here, and they want a black guy.’ I said, ‘Well General, you know this is all published, and open and aboveboard.’ He said, ‘Don’t tell me problems; tell me solutions.'”

After giving it some thought, Yeager came up with a solution. He told LeMay that if they would give him money for a few extra students, he’d include Dwight.

Yeager described Dwight as “an average pilot with an average academic background.”

“He was a nice guy, but he was just not qualified to be in the school,” Yeager said. “It was primer stuff for Dwight. Basically, he could not hack the program. All of the staff tutored him and tried like mad. It was a shame.”

Yeager said that Dwight “hung on and squeezed through,” getting his diploma qualifying him to be the nation’s first black astronaut, but that NASA didn’t select him. Then, a “few powerful supporters in Washington” demanded to know why.

“Dwight said we were picking on him,” said Yeager. “There was none of that. He wasn’t aware of everything that went on in the school. In fact, the guys on the staff busted their butts to try to get him through the course, and it just didn’t work.”

When the term “racist” was thrown at Yeager and the Air Force, Yeager bristled. Speaking for the Air Force, he said, “There were no black pilots or white pilots in the Air Force. There were only pilots who knew how to fly, and pilots who didn’t.”

He also spoke for himself.

“Hell, in the county I was raised in, in West Virginia, I never saw a black guy until I was about 14,” he said. “There weren’t any back there then. But the ones that served in my squadron, like Emmett Hatch, they were sharp. I wish I could have got them into the school, but they didn’t want to get involved.”

Yeager said the only “prejudice” against Dwight was a conviction shared by all the instructors that he wasn’t qualified to be in the school.

Crash And Burn

In 1963, Lockheed delivered three special rocket-powered F-104 Starfighters to the space school for use in high-altitude, zero G training.

On Dec. 12, 1963, Yeager, piloting one of the aircraft, climbed to 35,000 feet, then 37,000 feet, in afterburner. Traveling at Mach 2, he planned to go into a shallow dive to allow the engine blades to windmill in the rush of air, working up the necessary revolutions enabling re-ignition in the lower air, at about 40,000 feet.

Shutting down the engine, he let the rocket carry him over the top, at 104,000 feet. As the airplane completed its long arc, it fell over. But as the angle of attack reached 28 degrees, the nose pitched up, and his thrusters had no effect.

“I kept those peroxide ports open, using all my peroxide trying to get that nose down, but I couldn’t,” he said.

The nose was stuck high, and the airplane finally fell off flat and went into a spin. The data recorder would later indicate that the airplane made 14 flat spins from 104,000 until impact on the desert floor. Yeager punched out after 13. Yeager was hospitalized for nearly a month. Friends like Anderson who came to see him were initially puzzled when they first heard his injuries included first-, second- and third-degree burns. They questioned: from ejecting?

Yeager explained that an automatic device unhooked his seat belt and released the parachute ring from the seat. Then, a “seat-butt kicker,” another small charge, kicked him out and straight down. The seat, which had somehow gotten tangled up in his parachute shroud lines, fell with him. There was still residual fire in the back of the seat, and when the chute popped, the seat hit his face.

“I got clobbered by the rocket-end of that chair,” he said. “It just knocked the shit out of me.”

After he landed, he pulled the burnt lines apart with a slight tug.

Commander Of The 40th Fighter Wing

When the space training function ceased in 1971, the school reverted to its original role of training military test pilots. But not before 37 graduating students were selected for the U.S. space program; 26 earned astronaut’s wings flying in the Gemini, Apollo and space shuttle programs.

In 1966, Yeager was assigned to Clark Air Base in the Philippines. As commander of the 405th Fighter Wing, he was in charge of five squadrons scattered across Southeast Asia.

Besides a squadron of fighter-bombers on Taiwan, armed with nuclear weapons targeted into China, he was in charge of two squadrons in Vietnam, one of B-57 Canberra bombers at Phan Rang, and an air defense squadron at Da Nang. He also oversaw a detachment of fighters in Udorn and Bangkok, in Thailand.

During that two-year period, while responsible for 5,000 men under his command, Yeager said he managed to squeeze in 127 combat missions.

While commander of the 405th FW, Yeager was recommended to become a wing commander of tactical fighters in Vietnam. The wing was located at Phan Rang, where he had a squadron of B-57s. At Clark, Yeager had been under the command of the Thirteenth Air Force, headed by General Wilson. His new assignment would have placed him under Gen. William Momyer, who headed the Seventh Air Force, and would have meant he would lead combat squadrons flying in the north.

However, Momyer told the Pentagon he picked his own commanders and that he didn’t want Yeager. Shortly thereafter, the Pentagon assigned Yeager to take over a TAC wing of F-4 Phantoms at Seymour Johnson in North Carolina.

“We were the first deployed to South Korea during the Pueblo crisis,” Yeager said.

They were there for six months. By then, Yeager’s oldest son, Donald, a paratrooper, was fighting in Vietnam with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, and Yeager made trips in an F-4 Phantom from Korea to visit him.

“I would have to sneak in because Momyer was still in command,” he said.

He also managed to fly a combat mission with Anderson. A wing commander, Anderson was stationed at Okinawa, but spent most of his time with his squadrons based in Thailand.

“He flew in the back seat of my B-57, and we went out and bombed a bunch of trees at the direction of a forward air controller, who thought V.C. were hiding down there,” Yeager recalled.

In the fall of 1968, they deployed from Korea back to their base at Seymour Johnson. All three of Yeager’s F-4 Phantom squadrons made it back with no aborts.

Because Yeager maintained a unique perfect deployment record in TAC, General Disosway, TAC’s commander, wrote a glowing commendation. But a couple of months after Yeager returned to the States, TAC got a new commanding general, Gen. Momyer. Yeager told his wife they’d better pack their bags. He was right.

After an instance in which the four-star general thought Yeager should have gotten his permission to take up an assistant secretary of the Air Force, who had expressed a desire to go up in a fighter, Momyer told Yeager there wasn’t enough room in the command for both of them.

“What a jerk!” Yeager said. “I never knew what his grievance was.”

Expecting the worst, Yeager was surprised when shortly after that he found out his name was on the promotion board list as “brigadier general.” He wasn’t surprised to discover that it wasn’t Momyer who had recommended him. In fact, he hadn’t even been consulted.

Retirement

In March 1973, General Yeager returned stateside to take over as USAF director of aerospace safety at Norton AFB, California.

On Feb. 25, 1975, he returned to Edwards AFB for his last official active duty flight in an F-4C Phantom II. Upon climbing out of the cockpit that day, he had accumulated 10,131.6 hours, in about 180 types and models of military aircraft.

Three days later, he completed his active duty service during ceremonies at Norton AFB, attended by dignitaries including Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, Maj. Gen Albert Boyd and Jackie Cochran.

After a 34-year military career, Yeager retired on March 1, 1975. The following year, he was presented a special peacetime Medal of Honor, after Cochran lobbied diligently for it.

Yeager might have retired from the military, but that didn’t end his chances of flying military aircraft.

“Since I’d spent most of my time in research flying, the Air Force asked if I’d serve as a consultant test pilot to the Flight Test Center at Edwards for a dollar a year,” he said.

That allowed him to log time in the F-15 and F-16 Falcon, as well as areas in stealth technology computer flight control systems, some standoff weapon systems and unmanned vehicles. Although the dollar was just a “token amount,” Yeager loved the idea; he didn’t adjust easily to the lack of demands on his time during the first few months out of the service.

He still spent a lot of time at Edwards, flying every chance that he got, and Northrop hired him as a consultant, which gave him a chance to fly the F-20 and F-5.

On Oct. 14, 1997, Yeager returned to Edwards to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his milestone flight in the Bell X-1, by breaking the sound barrier in an F-15 Eagle. Five years later, on Oct. 26, 2002, he again broke the sound barrier in an F-15, at the Edwards 2002 Air Show. He took the F-15 Eagle to just over 30,000 feet on his last supersonic flight (with test pilot Lt. Col. Troy Fontaine in the back seat); the plane reached Mach 1.45. On that day, he finished 60 years, one month, in Air Force cockpits.

“I had flown some 208 types of military airplanes all over the world. So, I hung it up,” he said. “No one will ever be given that opportunity again.”

Over the years, Yeager also worked for different aircraft companies as a consultant and flew demonstrations.

“I was flying the F-20 for Northrop and the F-18 for McDonnell Douglas,” he said. “Since the Air Force wasn’t paying me, I could work at the Air Force as a consultant test pilot without getting into conflict of interest.”

Today

Yeager continues to fly today.

“I fly P-51s, Huskies and floatplanes, things like that,” he said.

He also took up hang-gliding and flying ultralights. He adds that he’s never owned an airplane in his life. He explained that Jack Roush, of NASCAR fame, built one P-51 and had it painted like Old Crow, the Mustang Anderson flew during WWII.

“Right now, Jack has just finished another P-51 and he’s painted it Glamorous Glen III,” Yeager explained.

Yeager was shot down while flying the first Glamorous Glen and Glamorous Glen II was also shot down.

“I was flying Glamorous Glen III when I finished the tour,” he said. “Another friend of mine in North Carolina painted his P-51 like Glamorous Glen III, which made a smokin’ hole a couple of years ago.”

Yeager and Anderson, who live near each other in Northern California, still fly together often. The two recently visited Switzerland, and had another look at Mount Blanc.

“French President Chirac authorized both Andy and I to receive the French Medal of Honor (Officer of the Legion of Honour),” Yeager said.

Yeager continues to speak for various groups, and recently participated in an X-1 panel at the Society of Experimental Test Pilots’ annual conference, where Hoover and Cardenas joined him.

As for the woman whom he had four children with, and whose name graced his beloved aircraft, after going through successful chemotherapy treatments for an earlier bout with cancer of the pelvic and abdominal area, she succumbed to ovarian cancer in 1990.

‘We were married for 45 years,” Yeager said.

The Second Time Around

On Aug. 22, 2003, Yeager, 81, remarried. Two years before that, he had just returned from Melbourne, Australia, where he had been speaking, when he decided to take his usual walk on a mountain path near the Yuba River.

“Victoria asked me what I was doing on her trail,” he said with a smile. “I said, ‘Your trail? Hell, I’ve been walking this thing for a couple of years.'”

Yeager found out that she had just returned from South Africa, and she found out that he had been a fighter pilot. After they had spent quite a bit of time together, he decided he shouldn’t let her get away.

“I thought I’d better glom onto her,” he grinned.

Victoria Yeager, the president of the General Yeager Foundation, has been a big asset to her husband.

“She’s a marvelous help,” he said. “She’s as sharp as a tack on computers, schedules and has a tremendous memory; she can hear a gnat fart at a hundred yards, and can see like a hawk.”

The foundation began with Al Neuharth, the founder of USA Today, who founded the Free Spirit of the Year Award, through which he split one million dollars between four “free-spirited types.” Not surprisingly, Yeager received $250,000, with which Victoria helped him form the General Chuck Yeager Foundation. With that money, plus other money Yeager has received for signing pictures, and donations, they support student programs such as one at Marshall University in Huntington, W.V.

“They have a Yeager scholarship program where they bring in 20 students from all over the United States each year; they get four years of everything free, including a year of foreign study at Oxford,” Yeager said. “It’s wonderful.”

Additionally, donations have gone to the EAA’s Young Eagles program.

Victoria, who worked in the movie industry in the past, and has a business administration diploma, is now taking flying lessons.

Young Eagles And Other Involvements

Seven years ago, Yeager replaced actor Cliff Robertson as the director of the Young Eagles program. He’s flown over 200 Young Eagles, and on, Dec. 17, at Kitty Hawk, he’ll fly the millionth Young Eagle.

During EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2003, the Can-Am Partnership, representatives from the U.S. and Canadian governments, sponsored a day for Make-A-Wish Foundation children for the 13th consecutive year. As part of the event, Yeager piloted EAA’s classic 1927 Ford Tri-Motor for some unique Young Eagle flights for the children.

“They get a big charge out it,” he said. “They’re happy as hell, and it kind of gets to me; you look at these kids smiling, and you know a year from now they’re not going to be here.”

This summer, he asked his good friend Barron Hilton, whom he met a couple of years ago at Oshkosh, to accompany him.

“Barron is such a wonderful photographer; he took some fabulous pictures,” he said.

Yeager said he became acquainted with Hilton when the avid fisherman asked him to go salmon fishing in Alaska. However, he says he’s never visited Hilton’s famed Flying M Ranch, which is a favorite hangout for many pilots, including several astronauts.

“I suppose that as a military guy who’s NASA’s worst critic, I’m not liked by most astronauts,” he grinned. “I’ll put it this way, they don’t love me.”

Yeager admits that it’s true that Hoover feels right at home at the ranch, and offers an explanation as to why.

“Bob is a different guy, because he’s famous as an aerobatic pilot. I’m not famous for anything,” he says.

For more information on Chuck Yeager, or to donate to the General Chuck Yeager Foundation, visit [http://www.chuckyeager.com].

Barron Hilton (right) joined Chuck Yeager on a special Young Eagles/Make-A-Wish Foundation flight during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2003, in EAA’s classic 1927 Ford Tri-Motor.