“All through your life, you meet people and do things that change the course of your life,” Clay Lacy reflects. “Different things impress you at different times.”

The course of Lacy’s life has definitely held twists and turns, but really, it’s always had one central theme, leading him to say that he’s led a very “narrow life.”

“It’s always been in aviation,” he explained.

Lois Lacy says if her husband ever has time to pen his bio, he should name it, “The Planes I’ve Flown and The People I’ve Known.” Why?

Lacy, the founder of Clay Lacy Aviation, has flown more than 300 different aircraft types. He has over 30 different type ratings and holds 29 current world speed records. As for flight hours, he’s accumulated over 50,000—reportedly more than any other human. He logged those hours in various areas, including military and test flying, air racing, aerial photography, aircraft sales and a four-decade-and-seven-month career with United.

“I really overdosed,” he says with a chuckle.

And, his involvement in aviation has definitely led him to meet “a lot of interesting people” including aviation legends, presidents and celebrities. His history intertwines with that of Bill Lear, Allen Paulson, Jack Conroy, Danny Kaye and others.

As he begins to tell his tale, his good friend John W. Myers, 92, listens attentively. Myers, who at one time served as chief pilot for both Northrop and Lockheed, still flies his own Citation II.

“I know what I’m talking about, and he’s the finest pilot in the whole damn world,” he says of Lacy.

Every now and then, he contributes to the story, usually with a clarifier: “And he did all this WHILE he was flying for United!”

Clay Lacy has flown more than 300 different aircraft types, has over 30 different type ratings and has accumulated over 50,000 flight hours, reportedly more than any other human.

“The Air Capital of the World”

When asked if the rumor is true that Lacy produced a family Bible in his latter years with United to prove he was a year younger, for one more year of flying, the answer is, “Absolutely not!”

“It was two years and I straightened it out with my birth certificate,” he chuckles. “My certificate was off by two years.

As to why his certificate was off, frankly, it was due to a small fib. But let’s begin at the beginning. Lacy knew what he wanted to do with his life since he was 8 years old. Thankfully, he had several people before and after then steering him in that direction.

It helped that he was born in Wichita, Kansas, the “Air Capital of the World”— home to Beechcraft, Cessna, Mooney, Swallow and many other aircraft manufacturers.

And his father, in direct and indirect ways, also contributed to his desire to fly.

“My dad got tuberculosis when I was about 4, and had to go to a TB sanitarium,” Lacy said. “It was about a mile away from Wichita Municipal Airport. My mother went there on Saturdays and Sundays to visit him, but I couldn’t go in; I had to stay in the car. I would sit there, near final approach, and watch those airplanes. I could see them all coming over fairly low and landing.”

During that period, Lacy’s dad temporarily got better, and came home for a few months.

“When I was in the first grade, TWA brought a DC-3 to Wichita, and put it on display for a day so people couple come out and see it,” he said. “My dad took me out of school that day to go out and see it.”

Another person who influenced young Lacy was Clarence Clark, a neighbor. Clark had been chief pilot for Beech at the Travel Air Manufacturing Company. Later, he had gone to work for Frank Phillips, founder of the Phillips Petroleum Company, whom he met when Phillips arrived in Wichita to demo a Beechcraft model. In 1927, Phillips created one of the earliest corporate aviation departments, hiring Billy Parker to head it. He also opened Frank Phillips Field, in Bartlesville, Okla.

After Lacy’s father died in 1939, Clark and his wife invited Mrs. Lacy and her 7-year-old son on a trip to Bartlesville.

“We stayed there about four days, and Clarence took me out to the airport with him, when he went out to the office. He didn’t fly during those four days,” said Lacy. “Phillips had the most beautiful flight operations department. The floors were painted and the airplanes shined. They had two Lockheed Model 14s (Super Electras). They had just gotten their first Lodestar (Model 18). He let me sit in the airplanes.”

The flight department was definitely impressive, as was something else involving Clark. On a trip through South America, he had brought along an 8-mm movie camera.

“He took these pictures out the window, and you could see the Andes Mountains sticking up through the clouds, and everything,” Lacy said. “Boy, when I saw those movies, and went down to Phillips 66, there was no question in my mind what I was going to do. I was really hooked on airplanes.”

There were other people and situations in those early days that firmly cemented his future. When he was five, he was tutored in the art of airplane model building by eight-year-old Fred Darmsetter, his next-door neighbor. (Darmstetter now lives in San Antonio, where he works for an oil company. About three years ago, Lacy showed his gratitude for those early lessons by chauffeuring him back to Oshkosh in a DC-3.) Lacy also recalls that he graduated to gasoline-powered models about four years later, through another friend.

It was shortly after his dad died that Mrs. Lacy took her son for a ride in a Staggerwing Beech.

“The pilot’s name was Dave Petersen,” Lacy recalled. “He used to fly over town on weekends every 15 minutes.”

The person most influential in getting young Lacy into the air for good, however, was Orville Sanders, who begun buying surplus liaison aircraft such as the L-4 (Piper Cub) and L-3 (Aeronca) shortly before World War II ended.

“Orville was a wonderful guy who helped me so much,” Lacy said. “He was having a guy bring these airplanes in to a golf course that was next door to my grandmother’s farm. They were landing on a fairway. They’d land either in the morning, or when nobody was there. This guy was letting Orville pull them up along a hedge there, by the highway. I wasn’t old enough to have a driver’s license but I had a motor scooter (a Cushman) out there on the farm. I already knew a lot about airplanes so I started stopping there and talking to him.

“When I met Orville, he was out there painting with dope and things, barely sanding the stars off; just repainting. Hell, these airplanes were just a year old. I started helping him paint airplanes and do other things. I knew quite a bit about dope, and how to use a spray gun. I probably knew more about it than Orville did, because he was just getting into it.”

In exchange, Lacy received flight time.

One day, Sanders told Lacy his dream of building an airport, and expressed that his grandmother’s farm would be the perfect site.

“I talked to my grandmother. She knew nothing about aviation, and had never flown in an airplane,” Lacy said. “Her son was farming the land, but she said she’d talk to him, because she knew how bad I wanted to fly. They made a deal, and she rented him initially about 40 acres, enough for a half-mile runway and an area for hangars.”

In 1945, Sanders established Cannonball Airport, named for its proximity to the “Cannonball Highway” (U.S. Highway 54) and later renamed Westmeadows.

“After he put the airport in, and I started flying solo, he would send me all over to get airplanes,” said Lacy. “He thought I could fly anything. He would send me to get airplanes I never checked out in, and a lot that I’d hardly even seen—just pictures. I mean, reasonably complicated airplanes at that time.”

Lacy enjoyed working at the airport so much that he regularly arrived there one summer month even when it was shut down.

“Orville took a partner in,” he said. “They shut it down for a month, because they were squabbling. They put it in receivership. There was no activity. I just stayed out there, because he asked me if I could watch the place, for flying time later.”

Although Lacy says he’s led a “narrow life,” since his career has always been aviation-related, in truth, he diverted once. At 13, he didn’t mind the fact that the work he was doing didn’t pay anything but flight time, but he did get a little envious that his next-door neighbor, who worked in a grocery store, usually had pocket money.

“He had a few bucks to spend on things,” Lacy said. “I didn’t realize that I didn’t really care if I had any money. All I did was go to the airport, anyway. My mother and grandmother would give me just enough money to be able to get there and back. Anyway, I thought I needed to get a job, so I got one in that grocery store.”

Lacy recalls that he reported in about six a.m. one morning.

“The guy showed me how to shoot water to clean off the produce, keep them wet, and a few things like that,” he said. “The whole time I was there, I kept thinking about the airport. By about nine o’clock, I was thinking, ‘This is a real drag!’ About 11 o’clock, I told the guy, ‘Sir, I think I’ll only work today.’ I was supposed to work until 3, I think. He said, ‘Well, that’s okay. In fact, if you want to take off at noon, take off.’ He gave me probably about three bucks for six hours. I took off and went back to the airport.”

Flying with United

With all the experience he was getting, Lacy decided it was time to get a student permit. He did so at the age of 14. With that piece of paper—which added an additional two years to his age—it was easy for Lacy to gain his private pilot license and instructor’s rating two years a head of time.

And that is how, at the age of 19, with 1,500 hours already logged, he was able to persuade United Airlines to hire him, in January 1952.

“I was so lucky to get a job with United at an early age,” he said. “That set a lifetime career for me.”

The supposed 21 year old was sent to Denver for training, and would soon be copiloting a DC-3.

“In those days, new hires usually went to Chicago or New York,” Lacy explained. “I was the youngest and had last choice, but all the other pilots were either from New York or Chicago, so that gave me the choice of Los Angeles or San Francisco.”

Lacy gladly chose Los Angeles.

Diversification courtesy of the Korean War

Lacy was enjoying his position with United, when, due to the Korean War, the draft board began sending him messages.

“I was afraid I would get drafted in the infantry or something,” he said. “I went through all my options and I found out about the Air National Guard, right here at Van Nuys. They had a program where they could send you to Air Force pilot training. I got in that program, and took military leave from United, starting January 1 of 1954.”

At that time, the California wing was flying the North American P-51 “Mustang,” but they were soon to transition to the North America F-86 “Sabre,” a swept-wing jet fighter. Because of that, Lacy headed to Nellis Air Force Base for training in that aircraft. He returned to the California ANG in August 1955, where he would fly the F-86, and later, the T-33 and C-97.

Upon his return, Lacy would be very active with the Guard, as well as flying a full schedule for United.

His experience in the area of instrument flying would help his wing in a definite area of weakness for Guard pilots, and eventually put him in charge of instrument training. In early 1956, the Air Force was scrutinizing the Guard in that area.

“The Guard was under a lot of pressure,” Lacy said. “Most of these fighter pilots weren’t very current on instrument training. Fighter pilots don’t fly much instrument time. Plus, when you get to jets, you go a lot faster, further and higher. They were having quite a few accidents, especially on cross-countries, where weather was involved. I think we’d lost seven airplanes in one year.

“The Air Force was on us. Smokey Caldera came over and gave us a big talk, and said he was giving us an award. Everybody thought, ‘An award for what?’ He said they’d researched the entire free world and we were directly ahead of the Chinese Nationalists, in Taiwan, on the number of accidents per flight hours flown.”

With this in mind, the wing was facing a random operational readiness inspection.

“They evaluated different classes of readiness, from instrument training, to gunnery to formation,” Lacy said. “The military advisor worked it out where I would be the ‘random’ guy who was going to do the instrument flying. He always acted like he didn’t like airline pilots, but he figured I knew how to fly.”

Lacy went up with a major whom he succeeded in completely befuddling.

“We flew cross country and shot an approach, I think at Fresno,” Lacy said. “Then, we came back here. Van Nuys didn’t have any instrument approach in those days, but I had all these approaches figured out off of the Burbank localizer. I decided that’s how I was going to receive.

“This guy had never heard of that. When we made an approach on Burbank ILS, for Van Nuys, he heard me transmit, but he never heard anything on the radio, any feedback, when I would talk. I should have been explaining to him what I was doing, but I wasn’t. When we landed, he said, ‘How in the hell were you receiving?'”

Later, during debriefing, in which Gen. Clarence A. Shoop, wing commander, and Col. Bob Campbell, group commander, were present, the major explained his system, in which he rated formation flying, instrument flying, etc., from one through 10.

“This major gets up and he says, ‘I never have seen a 10 on one of those reports, but I have to give you a 10 on this instrument training section. He said, ‘I only flew with Lt. Lacy, but he was so good, I didn’t know what was going on half the time!'” Lacy chuckles.

The major added that if Shoop or Campbell got a chance to, it would be worthwhile to fly with Lacy. Later, Shoop took Lacy aside, and told him anytime his United schedule permitted him to get away on Saturdays, he’d love to fly with him.

“He said, ‘I’m real weak, rusty on instruments. When you kind of get me in shape, start on Bob here,'” Lacy said. “They really wanted to get up to speed. I flew with Shoop some, but I really flew a lot with Campbell. He worked religiously at it. I got him to where he was very proficient, and then he could instruct it.”

Lacy also began developing training syllabuses.

“When we went to summer camp, Bob Campbell started giving check rides to the group operations officer, then the squadron commanders, and then the squadron operations officers,” Lacy said. “He was failing all of them. They were all mad at me. He really got behind the program, and we really did get our instrument proficiency. We went from the worst accident record in the whole Air Force practically, to an award by 1957 or 1958—most improvement, best instrument training program, and all that.”

Lacy says going through Air Force pilot training and being a member of the Guard was instrumental in many ways for different roles he would play in aviation later.

“It was a great place,” he said. “There were so many great people there that I got to know.”

One person Lacy would meet during that period was Jack Conroy, who would become one of his best friends.

“Immediately when we met we got to be great buddies,” he said. “He was an airline pilot. No one in the Guard in those days was an airline pilot except Conroy and me. He was flying all the different airplanes. He checked me out on the B-25, C-47, all these airplanes that other people weren’t flying. Of course, I was flying DC-3s on the airline.”

Through Conroy, Lacy met two of his childhood idols, Herman “Fish” Salmon and Tony LeVier. Lacy says he knew all about the Lockheed test pilots/midget airplane racers through magazines he read when he was a teenager. He remembers walking down the road one night, in either 1947 or 1948, and spotting two cars pulling trailers.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes,” he said. “On the trailers are these airplanes with the wings off; Cosmic Wind was the one Tony flew. I would have loved to have just seen those guys!”

Lacy chuckles and says, “It turns out they were in a bar. They were getting tired of driving. I found out all that later, when I told them about it. LeVier says, ‘Why the hell didn’t you come in? I said, ‘Number one, I was under age to go in a bar. And, I wouldn’t have had the nerve to go up and talk to you.’ We all got to be great friends later.”

Executive aircraft sales and the Pregnant Guppy

Conroy also introduced Lacy to Allen Paulson, who would become another good friend and play an integral part in another facet of Lacy’s career.

In 1952, Paulson, a TWA flight engineer who had served in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, formed California Airmotive at Burbank Airport. After meeting Paulson, Lacy would spend quite a bit of time flying with the pilot.

“He had a private pilot’s license, but he didn’t have an instrument rating,” he said.

Lacy said that at first, California Airmotive was mainly a parts business, but once surplus aircraft began flooding the market in the late fifties, Paulson began buying and selling various aircraft.

“They were beginning to surplus quite a few by 1958,” Lacy said. “The first airplanes he bought were three Convair 240s; Western had turned to Lockheed Electras. Later, he bought all of TWA’s Martin 404s. We sold those, 240s and Convair 340s for corporate airplanes.”

In the process, said Lacy, there were a lot of trade-ins.

“DC-3s and that sort of thing,” he said. “I was flying everything—Lockheed Lodestars, Learstars, you name it.”

In 1959, Lacy was juggling three aviation careers. He still had a full schedule for United. Besides ferrying aircraft for Paulson, he would also usually train pilots for the aircraft that were sold. And, he was still active in the Guard. In fact, his connections through the Guard continued to supply him with opportunities. For example, General Shoop was vice president of operations for Hughes Aircraft.

“Through him, I got a lot of connections and even business from Hughes, with the airplanes that Al Paulson and I were selling,” he said.

At that time, he estimates he flew 120 hours a month, but sometimes up to 140.

“If I had to relive my life and just drive the speed limit, I’d be two years behind,” he chuckles. “I’d get out of an airplane in LA, run and get in my car, go tearing over to Burbank, and take off and go do something else. I was crazy; I really went way overboard, but I had a lot of fun!”

To make all of the pieces fit together, Lacy sometimes traded trips with other United pilots, and the airline graciously let him drop others. Then, in 1960, Lacy went to Denver for a year to work in United’s flight training center.

“I would work about four days a week, then come back,” he said.

In September 1961, he was recalled to active duty with the Guard, due to the Berlin Crisis.

“We stayed at Van Nuys, so I could continue with my other activities,” he said. “By that time, we’d switched to the C-97, which was a transport plane. We never did go to Berlin. We flew primarily to Japan, with some trips to Vietnam.”

Lacy remained on active duty until Aug. 30, 1962. Following his release, he would begin flying as captain on the Convair 340, after which he would quickly move to the DC-4, DC-6 and DC-7.

In September 1962, Lacy and Conroy test flew the Pregnant Guppy.

Conroy, said Lacy, had left the Guard, but returned when they began flying the C-97. Later, he decided he wanted to start an airline in Hawaii, and began thinking of doing so with Boeing 377 Stratocruisers.

“The Stratocruiser wasn’t successful from an economic standpoint, but, they were wonderful for passengers—probably the epitome of comfort,” said Lacy. “It had a lounge downstairs. With United, for instance, if you were flying to Hawaii, you’d go down a circular stairway, and there would be a Hawaiian guy down there fixing drinks. And they had sleeper versions, like Pan Am; probably 30 people could have full sleeping accommodations.”

Conroy had heard that Lee Mansdorf in Burbank had acquired several surplus aircraft, including Stratocruisers, and decided to visit him about leasing or buying a couple. When he did, he found out that Mansdorf was working on another idea. He wanted to modify an aircraft to transport the Saturn launch vehicle.

“Mansdorf had planned to open the top of it like a clamshell, and lower the booster in there with a big crane,” Lacy said. “Well, Jack had a better idea. He thought they could take the tail off, slide the booster in, and put the tail back on. Jack got into that program, and was successful in building the Guppy in a period of about a year.”

With financial backing from Lloyd Dorsett, the two men formed Aero Spaceline, and work began on the conversion, including lengthening and enlarging. Wernher von Braun, NASA’s rocketry chief, made a couple of interested trips to Van Nuys.

“Jack really needed some kind of letter saying that NASA would use it, because he was running out of money; von Braun couldn’t give him the letter because they didn’t have money appropriated for it,” Lacy said.

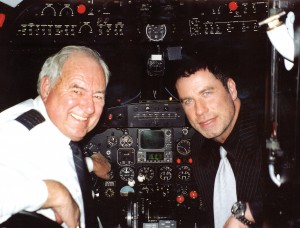

As a surprise birthday gift arranged by his wife, Kelly Preston, Clay flew John Travolta, his family and friends on a night flight along the California Coast in Clay’s vintage DC-3. Having a real love of aviation, particularly old airliners.

With Conroy, Lacy made the first flight, on Sept. 19, 1962, from Van Nuys to Mojave. In September 1963, the Pregnant Guppy, the first in a series of Guppies, made its first payload flight for NASA. When it was finally retired in 1974, it had logged more than 6,000 hours.

The Lear Jet

By early 1964, Lacy had resigned from the Guard.

“I just didn’t have time for it,” he said.

One of the reasons was his recent involvement with the Lear Jet. The jet and its inventor are popular subjects during a rowdy storytelling session at Barron Hilton’s Flying M Ranch on one recent evening.

“Bill had several one-liners,” says Lacy. “If someone said, ‘You can’t stand up in it!’ he’d say, ‘Can you stand up in a Rolls Royce?’ If they said, ‘It doesn’t have a galley—for food!’ He’d say, ‘If you want to get a meal, go to Club 21 or home; I built a little plane to get there in a hurry.’ If they said, ‘It doesn’t have an enclosed lav?’—because he had a little emergency lav, and if you really had to go, you could pull a curtain—he’d say, “I don’t know how many of my friends just want to fly around taking a shit!”

Also, Lear dismissed the size of his cabin, as opposed to more spacious cabins you could easily walk around in, by saying, “If you want to take a walk, go to Central Park.”

When Bill Lear decided he wanted to develop an executive airplane, he first studied the Marvel, a molded fiberglass turboprop designed and built for the U.S. Army by an engineering team headed by Dr. August Raspet. Lear liked the design because it was a pusher. He called Raspet several times in early 1959, with specifications for a pressurized five-place corporate airplane, and asked for his recommendations. He had his artist Ted Grobs draw the twin-engine turbo pusher, which metamorphosed on paper into the Lear Model 59-3, or, more specifically, the Eight Place Executive Airplane Twin Turbofan.

Then, in the summer of 1959, Lear asked Mitsubishi to bid on developing the prototype with him for what he would call the Lear-Mitsubishi Executive Transport Aircraft. Mitsubishi was interested, but wanted a small production contract to support the cost of developing the prototype. With things still up in the air, a year later, Bill Lear Jr. introduced his father to the P-16, a Swiss fighter-bomber he had test-flown, designed by Dr. Hans Studer, which didn’t make it as far as production.

Equally impressed, Lear Sr. hired Studer to help him convert it into a fast corporate jet. However, he didn’t have the blessing of his board at Lear Inc., in Santa Monica, and was advised to keep the Lear name out of the project, so he created the Swiss American Aviation Corporation. Work soon began on the SAAC-23. By mid-1961, the basic design of the aircraft was completed. On paper, it would cruise at 500 mph, with a max speed of 600, and have a range of 2,000 miles.

Lear was a little behind other American small jet designers. Lockheed’s JetStar and North American’s Sabreliner were already on the market, sporting a million-dollar price tag. But Lear considered his strictest competition the Jet Commander, which, like his jet, was still on the drawing boards.

In 1961, Elton McDonald, the owner of Sales Incentive Company and one of California Airmotive’s customers, who had recently acquired a Martin 404, called Lacy. He wanted the pilot to fly him from LA to Lear’s home in Palm Desert the following morning.

“Bill had asked Elton and Justin Dart, who was chairman of the board of Rexall, to come out and talk to them about the jet,” Lacy said. “He told them he was taking off to Switzerland, but before he went, he wanted some orders.’ Bill was taking orders for $275,000 apiece; he wanted $10,000 to get a delivery position. Justin gave him two orders and Elton gave him one.”

In 1962, with most of his attention focused on his jet, and needing the funds to develop it, Lear would agree to sell his stock in Lear, Inc., when the Siegler Corporation expressed an interest in merging with the company. His 470,000 shares, at $22 each, put $10.3 million in his pocket. Another 100,000 shares, in trust funds, gave him $2.2 million more.

He was also now able to call his jet whatever he liked, and chose the name Lear Jet. However, various problems in Switzerland soon compelled Lear to bring his project back to the States. Lacy laughs and says one was that he couldn’t talk to anyone there.

“Bill always wanted to go out in the factory,” Lacy said. “He’d ask every guy, ‘What are you doing?’ Then he’d say, ‘Well, why don’t you do it this way?’ But in Switzerland, they all spoke French, Italian or German. It drove him crazy.”

Lear would consider Wichita, Grand Rapids, Mich., and Dayton, Ohio, before moving the operation to Wichita. The City of Wichita had helped the decision by offering to raise $1.2 million in industrial revenue bonds for Lear Aero Spaceway, to be built on a 64-acre cornfield on the northern edge of the airport.

“At first, he bought a lot of the bonds himself,” Lacy said.

Ground was broken in August 1962. In January 1963, Lear and 75 employees moved into their new building.

One way Lear could stretch his money was by skipping the prototype step in the process. In October 1963, serial number 23-001, N801L, made its first flight from Wichita’s Mid-Continent Airport, nine months after initial assembly began.

Shortly after that, McDonald again called Lacy, and asked if he would make a trip to Wichita.

“Bill had realized he couldn’t build an aircraft for the original amount,” Lacy said. “He wrote a letter to everyone, saying he needed more money. It was still cheap, but Elton wanted me to see what was going on.”

Lacy recalls that after the initial 10 or so buyers, the price of the Model 23, bumped at that time to $375,000, would go to $545,000 and $595,000, for later buyers.

By then, Lacy was checked out in the Boeing 727 tri-jet, which United would begin flying in February 1964. When he arrived, Lear treated him like a long-lost brother.

“Bill would take anybody in that was interested in his project,” he chuckled. “I had known him from out here in California, before he started on the Lear Jet project, but not that well. I’d flown with him a couple of times when he was building autopilots, and on different occasions. Also, Bill Jr. was in the same unit of the Air National Guard, and he knew I was flying the 727, and knew a lot about jets.”

Lacy spent a couple of days in Wichita, during which time he often accompanied Lear around the facilities. Before he left, Lear asked him to return.

“He told me, ‘Any time you have off, come back here. Stay at my house.’ He offered me a hundred dollars a day to follow him around at the plant. I never turned in a bill,” Lacy chuckled. “I had a house there, because my grandmother had recently died. It was a mile and a half away from the factory. I started going back there. It was fun, because it was such an interesting, exciting time.”

Lacy’s first impression of the jet was that it performed like crazy, but that it was a “basket case.”

“Pressurization, hydraulics, you name it,” he said. “But old Bill corrected things in a hurry. When I first flew it, you’d add power, and the pressurization in the cabin would go down 10,000 feet a minute. When you’d take off, the power went off.”

Lacy explained to Lear that the 727 had a modulating valve, and told him he thought that was what the Model 23 needed.

“He said, ‘Well, I’ll find out how it works,'” Lacy recalled. “He started checking around.”

By February 1964, the flight test team had flown nearly 50 test flights, establishing a speed record during one flight of M.0905 (699 mph), making it the fastest business aircraft in the world.

By that spring, Lear had gone through deposit money, and had exhausted his bank credit against further deliveries. That worked in the favor of several who were hoping that Lear would change his mind about selling the Lear Jet through factory direct sales.

“He was going to have three colors and three interiors; that’s it,” said Lacy.

But as Lear got closer to putting the jet into production, he was running out of money at the same time.

“The banks had quit loaning him money, so he started thinking about a distributorship program,” Lacy said. “Anytime I had a chance, I would encourage him, because I thought that was a good idea. Then, he really started considering it, because he figured he could get five distributors to order five airplanes, and have them put down a healthy deposit on each.”

As Lear thought about it, Lacy talked to Paulson about the idea as well.

“I wanted him to go back and see the airplane, meet Bill and see if he could get a distributorship,” Lacy said. “He was always busy. I had interest in a Mustang, and one day he said, ‘Why don’t we fly the P-51 back there tomorrow? We flew to Wichita. I think that was around April of 1964. Al got a flight in the number-two jet. He had never been in any kind of a jet; he was impressed. Then he really wanted to get into the distributorship. I kept going back to see Bill, and I’d ask him what was going on with the program. Bill wanted me to be involved with selling them. We got the distributorship and probably set it up in about July of 1964.”

Lear divided the country into six sales regions. It was decided that California Airmotive would be the Lear Jet distributor for 11 Western states, serving that purpose out of Van Nuys Airport. Lacy, who served as manager of sales, would be one of the first pilots to receive a Lear type rating.

Money coming in for franchises and deposits on jets did supply Lear with funds, but it didn’t look like even that would see the jet through certification. However, in the meantime, help came in an unexpected way. In early June 1964, Lear test pilot James Kirkpatrick and FAA certification pilot Donald Keubler, left seat, took Model 23 up to evaluate single-engine departures.

Keubler was evaluating the jet’s performance on one engine. After several successful runs, he forgot to retract the wing spoilers after one landing. The aircraft flew a short distance before crash-landing in a cornfield, off the end of the runway.

“Both pilots walked away from the wreckage unhurt, but the aircraft burned up,” Lacy said.

The landing had broken a fuel line. By the time firemen got the flames under control, there was nothing left but a charred airframe. What seemed to be a great tragedy held an unexpected blessing. After all, there would be insurance money. But, that wasn’t all. A second Model 23, Lear Jet #2, which Dart had bought, was at that time sitting in the hangar.

“Bill Lear got on the telephone and called everybody he knew that he thought could help,” Lacy said. “Some U.S. senators and high-level FAA administrators asked how they could help. Bill asked for the required FAA certification personnel to be available for Learjet flight-testing fulltime—around the clock if necessary.”

Lear received formal FAA certification on July 31, 1964, just seven weeks after the crash, and, four months before the Jet Commander was certified.

“He had 14.7 million dollars in it,” said Lacy. “Even in those days that was cheap.”

They had gotten through certification, but now Lear needed funds for production. Going public seemed to be the only way he could raise more money. He applied to the Securities and Exchange Commission for permission to offer Lear Jet common stock to the public.

On Oct. 13, 1964, the first production Model 23 was delivered, to the Chemical and Industrial Corp., of Cincinnati, Ohio. On Nov. 30, 1964, Lear Jet became publicly owned, when Lear sold 550,000 shares for $10 each, retaining a 60 percent ownership and remaining president and chairman of the board.

That same month, California Airmotive took possession of N1965L, serial number 23-012.

“When I brought that airplane to Van Nuys, it was the very first corporate jet on the airport,” Lacy said.

He explains the significance of the N number for their Lear Jet.

“I reserved a bunch of numbers, so that each year we could put a new number on our new demonstrator, if we stayed in business,” he said. “So, it was for 1965 Lear. I reserved that number through 1982 Lear.”

When N1965L arrived at Van Nuys, it wasn’t exactly in showcase condition.

“It just had raw seats setting in it,” Lacy said. “Interiors weren’t something they had set up for; they built the planes so fast, and they hadn’t thought that much about what the interiors were going to be like. We flew it around, gave some demonstrations to people. But then we said, ‘We have to get this interior in.’ I didn’t mind giving demos to pilots to see how the plane would perform, but if people were going to be riding in the back…”

The jet arrived back in Wichita in January 1965, and returned in April ready for serious demonstrating.

“In addition to flying for United, I was flying that jet probably close to 100 hours a month,” Lacy said.

With the idea of quickly getting the Lear name to the public, Lear asked Lacy to help him.

“He called me one day from the Beverly Hilton,” said Lacy. “I went over and he asked me what I thought the direct operating cost was to fly the Lear Jet per hour. Jet fuel was about 14 or 15 cents a gallon. Engine overhauls were supposed to only be like $25 an hour. I figured around $150. Then, he told me to go through the phonebook and call anyone who he thought would talk up the Lear Jet, and give him or her a demo ride. He said, ‘Send me a bill every month for how many hours you flew,’ He also gave me a lot of names, like Art Linkletter and his friends.”

Of course, one of California Airmotive’s biggest advantages was their proximity to Hollywood.

“Come Fly With Me”

Frank Sinatra had been crooning about the romance of flight even back in 1957, when he recorded “Come Fly With Me.” He would be one of the first celebrities to fall in love with the Lear Jet.

“We flew Frank about 20 times or more,” Lacy said. “We sold him a Lear and he featured it on a special. We used to trade him time.”

Danny Kaye would do more than buy a Lear Jet.

“Danny had a Queen Air,” Lacy said. “I had barely met him, but I knew he flew, so I got a hold of his file and invited him out for a demo. He came out and I was flying with United. There happened to be a guy here from Lear Jet. He took Danny up and scared the hell out of him. Danny wasn’t going to fly in it anymore.”

Lacy called Kaye’s pilot and asked him where he might want to go. The pilot told him that Kaye and partner Lester Smith had a radio station in Portland.

“I called Danny and he told me he didn’t like the plane,” Lacy said. “He said that it was hard to fly. I said, ‘Do me a favor? Fly in it again. We’ll fly to Portland.’ He said okay, so we flew up there. He loved how fast we got there.”

The following day, Lacy took Kaye up to shoot landings.

“We shot landings for maybe an hour and a half,” Lacy said. “I knew how to not make a guy feel stupid, and to not let him get too far into trouble. I made him feel like he could fly it. I knew how to demonstrate it and make it a crapshoot. Danny became absolutely hooked on the airplane that weekend.”

Early the next week, when they flew back to Van Nuys, Bill Lear had just landed. “They met, and they got along great,” Lacy said. “Danny told me a few days later, ‘I just don’t want to fly an airplane. I want to get involved.’ That’s why, with a little pressure from Bill, Danny bought into the distributorship.”

At that point, California Airmotive became Pacific Lear Jet, whose principals were Paulson, Kaye and Bill Murphy, in the car business, who had also been a silent partner in California Airmotive. Lacy had a small ownership as well.

“I think it was five percent,” he said.

Lacy and Kaye spent quite a lot of time together in the cockpit. They flew about 200 hours together, including three UNICEF flights.

During the first year in operation as a Lear distributorship, California Airmotive/Pacific Lear Jet sold 14 jets. They demonstrated to a variety of people, including many business owners. Lacy says it surprised him to see how many heads of companies, such as Barron Hilton, of Hilton Hotels Corporation, and C.N. Ray, founder of Sea Ray Boats, were pilots.

“We’d sit them in the left seat, and let them do the flying,” he said. “It seemed like over half of the CEOs that flew had been pilots in the service and had their own airplanes. A lot of these guys had been fighter pilots. They were people that weren’t afraid to take a risk. So, after the war was over, a lot of them took risks, got into business, and did well.”

California Airmotive found several ways to promote the Lear name, including giving away flights in their demo for winners of the “Dating Game.”

“In the program, the guy had a model of the Lear Jet on his desk,” Lacy said. “Every week we gave a trip to the winners, from San Francisco or Las Vegas.”

In 1955, Conroy had set a coast-to-coast roundtrip speed record as the pilot of an F-86. Ten years later, on May 21, 1965, Lacy and Conroy, with five passengers on board, retraced Conroy’s earlier dawn-to-dusk transcontinental flight. The Lear 23’s 5,005-mile roundtrip from Los Angeles to New York and back of 10 hours, 21 minutes (elapsed time of 11 hours, 36 minutes) set several world records.

“We were the first to fly a civilian aircraft coast to coast between sunrise and sunset,” Lacy said.

That wouldn’t be the last record Lacy would set, in the Lear or in other aircraft. Also, by that time, Lacy had already participated in the inaugural National Championship Air Races & Air Show, at Reno. There would be more races to come. And, in the near future, he would enter the world of air-to-air photography and start his own charter company.

- Clay Lacy began flying for United at age 19.

- Clay Lacy and General Jimmy Doolittle, in June 1965.

- L to R: Clay Lacy, Bill Lear and Danny Kaye in Lear Jet mock-up.

- Jack Conroy and Clay Lacy review the route they will fly the next day, May 21, 1965, in Lear Jet N1965L, to set five world records (which still stand) and be the first civilian aircraft to fly coast to coast between sunrise and sunset.