By Di Freeze

Cliff Robertson, a pilot who happens to also be an Academy Award and Emmy Award winning screen star, says he remembers reading “Time Must Have a Stop,” by Aldous Huxley, years ago, and wondering about the title.

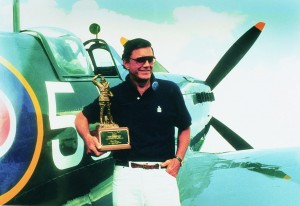

Cliff Robertson, with a Spitfire he acquired from the Belgium Air Force, was awarded the Experimental Aircraft Association’s highest honor, the “Freedom of Flight Award,” for his role in the organization’s “In Pursuit of Dreams” presentation in 1987.

“I never knew what he meant, but I’m beginning to realize now,” he said. “We need more time!”

Robertson would like more time to devote to his immediate family—his oldest daughter Stephanie, who lives in Charleston, and Heather, who lives in New York City—as well as to his closest friends, who are his “aviation buddies,” and to flying his airplanes.

That includes his Grob Twin Astir, a German two-place glider he keeps at High Country Soaring in Minden, Nev., on the eastern side of the High Sierras. He’s glided in and out of a few other places, but says that High Country, 38 miles south of Reno, run by Tom and Janice Stowers and Bill Stowers, is the best place to soar in the world.

“They’re good people; they’re like family to me,” Robertson said. “When I go up there, they put me in the back room. I spend two, three or four days. That’s my Walden’s Pond.”

He adds that glider pilots from around the world come to High Country Soaring, because the conditions there are so unique. Robertson’s been gliding for over 16 years, and has his diamond altitude, for over 26,000 feet. A few years back, he and a friend set a Nevada state record for distance in a two-place glider—240 miles, from Tonopah to Parowan.

He shares that passion with friends like Barron Hilton, whose Flying M Ranch is about 35 miles from High Country. Robertson will be there this summer to celebrate with the winners of this year’s Hilton Cup. But gliding is only a part of his aviation “obsession.”

“I have a big hole in my head and a stable of planes,” says the man who holds single-engine land and sea, multiengine, instrument and commercial licenses, as well as balloon, gliding and seaplane ratings.

Those planes include a Beech Baron 58; a Messerschmitt Me-108, which is on display in the Parker-O’Malley Air Museum in Ghent, in upstate New York; and a Stampe SV4, a French fully aerobatic open-cockpit biplane. In the past, he’s also owned three Tiger Moths, as well as a Spitfire Mk.IX.

Once Upon A Time In La Jolla

Born Clifford Parker Robertson III, on Sept. 9, 1925, Robertson was raised by his grandmother and an uncle, after his mother died when he was two and a half. He recalls becoming aware of aviation when he was five years old, living in La Jolla, Calif.

“I saw a little yellow airplane doing aerobatics over our house,” he said. “My uncle and another man were standing there watching the aerobatics, wagging their heads sagely, and one said, ‘You’ll never get me up in one of those little airplanes.’ Then the little airplane turned southward and started to hum its way home. We got into the Ford alongside the curb and it wouldn’t start. In my little mind, I was thinking, ‘What’s wrong with this picture?’ I think I began to become a partisan for aviation at an early age. I was defending it then, and I still am.”

Living 13 miles from San Diego, when Robertson was 14, during the summer, he began riding his bicycle, six days a week, into a “little sleepy airport.”

“Speer Airport had one little sandy runway,” he said. “I would go and work eight hours a day cleaning airplanes and engine parts and never got paid a nickel, but every third or fourth day, the chief pilot would say, ‘Cliff, go get your cushion.’ I was short for my age. I’d take my cushion out to a little red Piper Cub and he’d take me up for 15 minutes and let me at the controls once we took off. I thought I was the ace of aces. It was a magic time.”

From Off-Off Broadway To Hollywood

As many do who flirt with aviation in their youth, Robertson abandoned it for a period while sorting out what to do with his life. He served in the military for three and a half years; he was in the Navy and active in the Maritime Services, obtaining lieutenant junior grade.

Then, he attended Antioch College. He entered a program that allowed him to work at the same time, so he began writing for the Springfield Daily News. While working for the paper, he was told he should write for the theater “instead of a deadline,” because he had talent that would be more suited there than for writing general assignments for a newspaper.

“I said, ‘I don’t know; we’ll see,'” Robertson said. “Ultimately, I fell in with bad companions, and did off-off Broadway and Broadway.”

When he arrived in New York, he knew nothing about the theater.

“They said, ‘You have to go out and do the husking, go out into the regions, the provinces and learn about the theater, if you’re going to write for it,'” he said. “So, I went out and learned to drive a truck and build flats, and I didn’t take it very seriously. They looked at this callow kid. It irritated my fellow actors who took it and themselves very seriously.”

Robertson said he acted because everybody else in the company did.

“I had the audacity, in spite of myself, to get good reviews, which really ticked them off,” he said. “I was actually kind of hovering over making a living. I was kind of hanging in there in New York. I did a lot of things, but eventually I was making a living in the theater and then in early television and then finally Hollywood.”

After two years with a touring company, Robertson appeared in a few, small, un-credited roles in films in the late forties, and in television installments of “Kraft Television Theatre” in 1947, “Robert Montgomery Presents” in 1950, and “Rod Brown of the Rocket Rangers” in 1953 and 1954. His first credited film role was in “Picnic,” in 1955, directed by Joshua Logan, after starring in the Broadway production in 1952. That same year, he played Joan Crawford’s schizophrenic boyfriend in “Autumn Leaves.”

Over the next years he switched back and forth between TV and motion pictures, receiving accolades for his performance as an alcoholic in the 1958 Playhouse 90’s “Days of Wine and Roses” and in “Twilight Zone” and “The Outer Limits” installments, and playing roles including the original Big Kahuna in “Gidget” in 1959.

In 1961, Robertson took a completely different role—that of Charly Gordon, a mentally retarded bakery worker who becomes a genius after undergoing experimental brain surgery, in an hour-long Theater Guild television adaptation of Daniel Keye’s short story, “Flowers for Algernon.” Collaborating with the screenwriter hired by the Theater Guild, he wrote most of the second act of “The Two Worlds of Charly Gordon.”

“It got such recognition that I secured the film rights, thinking, ‘Now I can think of a movie,'” he said. “Up to that time, I was sort of always a bridesmaid and never a bride.”

Securing film rights was something Robertson hadn’t been able to do with “Days of Wine and Roses.” Jack Lemmon did that, and cast himself in the starring role in the film released in 1962.

“I can’t blame him,” said Robertson. “If I’d had his money, I would have probably done the same thing.”

Seven years would go by before “Charly” would be released as a motion picture. In the meantime, while working on a movie at Paramount, Robertson received a call from a White House representative, requesting he go to Warner Brothers the following day to do a test for “PT 109.” The film was the story of Navy Lieutenant John F. Kennedy’s fight to keep his crew alive when their boat sunk in the South Pacific.

“I said, ‘You’re kidding me,'” Robertson said. “They said, ‘No,’ and I said, ‘I’m working on this picture.’ The key words were, ‘It’s been arranged.’ When I heard it had been arranged, I knew it was by somebody big.”

That somebody was President Kennedy, who, upon hearing that a book written about his WWII South Pacific experiences was to be made into a movie, made three requests.

“One was that it be historically accurate, because Hollywood is not known for its accuracy; they have a tendency to exaggerate,” Robertson said. “Two was that any monies that would be coming to him, since it was a story about him, would be directed to the survivors of PT 109, which he commanded, or if they were no longer alive, to their families. Three was that he be allowed to pick the actor.”

Robertson said at that time there was a lot of talk about who was going to play the young Kennedy.

“I remember Warren Beatty was rumored, and Peter Fonda,” he said.

Robertson did the test; three days later, he learned he had the part when he received a call from a friend in New York who had seen his picture, alongside Kennedy’s, in the New York Times.

While doing “Sunday in New York” with Jane Fonda, Robertson received a call from the president.

“He asked me if I’d like to come down and visit, so I did,” he said. “It turned out he’d seen things that I’d done.”

“PT 109” and “Sunday in New York” were released in 1963. By that time, Robertson had traveled to England for filming. There, he found the opportunity to “seriously” get involved in aviation.

Something You Never Forget

While in England, Robertson decided to join the Fairoaks Flying Club in Chobham, Surrey.

“Being involved in aviation is like meeting a beautiful woman you never forget,” he said.

There, he soloed in a Tiger Moth, a de Havilland biplane that the English used in the late thirties to train young RAF pilots. He had decided that if he could land a biplane in a crosswind, he could land anything. He later joined other aero clubs.

He also acquired his first Tiger Moth, which he flew across the Channel to Normandy, France, to film “Up From The Beach.”

“I had it over there for a while during filming, and then shipped it over,” he said. “Then I worried about parts, so I ended up looking around and finding another Tiger Moth on the other side of the globe out at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. It was for sale for virtually nothing. I bought it thinking I could cannibalize it when I needed parts. When it arrived in San Pedro, we cracked open the case and it was in better shape than the first one. I ended up getting a third for the same reason. So, for a number of years, I was the proud owner of three Tiger Moths.”

While in England filming “633 Squadron” for United Artists, Robertson became interested in the de Havilland Mosquito bomber.

“In the film, we had probably the very last Mosquito bombers left,” he said. “We had five. I tried to buy one, so I could bring it back to America, but I was subverted by someone who will remain nameless, who screwed things up so nobody got them.”

Robertson said that during the filming, one Mosquito bomber was destroyed; the scene called for an airplane to hit a truck.

“To make it genuine, they had to make this bomber explode on the ground,” he said. “Nobody was in the cockpit, of course, but they had this special-effects guy running behind it with long wires, so he was able to trigger it off when it hit this truck. It exploded. That broke my heart. Then we watched it burn. It was called the ‘wooden bomber,’ because a lot of it was made out of wood, which made it very light, and fast. That central spar was made of very highly compressed wood. I watched it burn for over three hours, and that spar was still intact. It was amazing how strong it was.”

Although he wasn’t able to acquire a Mosquito, while filming, Robertson learned that the Belgium Air Force owned three Spitfires, another aircraft that attracted his interest.

“In World War II, they had been using them for towing targets for jets,” he said. “That was the fastest thing they could get, since they weren’t using jets to tow the targets.”

When he got back to America, knowing there were very few Spitfires left, he proceeded to see if he could buy one. He was able to acquire one that had the Belgian registration of OO-ARF.

“I got my friend Neil Williams, who had been Britain’s top aerobatic pilot and a test pilot for the Royal Air Force, to go over and get it,” he said. “He virtually begged me to let him fly it. Of course, everybody—particularly every Englishman—would give their right arm to fly a Spitfire, because there were not that many left.”

He said that later, Williams (who was subsequently killed while ferrying a Heinkel bomber from Spain to England, in the mid-seventies) wrote him an emotional and lengthy letter telling him what it meant to him.

Robertson said that the RAF was so desperate during World War II that some pilots went directly from the Tiger Moth, a very slow biplane, to a Spitfire, although usually they went to an intermediate plane.

When asked if he ever flew the Spitfire, Robertson grinned and said, “People ask me what it was like to fly a Spitfire and I tell them, ‘Well, I’ll give you the same answer I gave my insurance adjustor, which is, “Of course I didn’t fly it!” That’s my answer, and I’m sticking to it!”

Robertson had the Spitfire for about 20 years.

“I was having it worked on some of the time, in the States. When you get an airplane like that, it takes a lot of upkeep. It’s a queen and you have to treat it like a queen. Later on, I let Tom Poberezny keep it at EAA, so people could see it,” he said. “I also had it up at the Air Zoo, in Michigan.”

He said it was a similar situation to his Messerschmitt.

“There’s a provision that we can fly it when we need to,” he said. “I want the public to be able to see it, because it’s a piece of history, but if I request it, I’m allowed to take the Messerschmitt out and fly it. That’s the provision we had with both Oshkosh and the Air Zoo; that way we could keep it running and maintain it.”

About five years ago, Robertson sold the Spitfire to telecommunications pioneer Craig McCaw.

“He respects the airplane as much as I do, because he realizes it’s more than a fighter plane,” Robertson said. “That airplane saved western civilization as we know it today. People say, ‘How can you say that?’ Well, long before the atom bomb, they had the Battle of Britain, which turned the tide of World War II.

“In the Battle of Britain, no matter how those pilots flew, the Hurricane, which was a fine airplane, wouldn’t have tipped the balance against the Germans. The Spitfire did. Without it, they would have lost the Battle of Britain, and all historians agree. Had the Germans won the Battle of Britain, England would have had to negotiate with Germany, and Germany would then have been able to put its total forces against Russia, and they would’ve won. Had it not been for that one man, Mr. Mitchell, who designed it, the war would’ve been entirely different.”

Giving To Others

Robertson, a pilot of many thousands of hours, has accumulated various aviation awards. He’s a recipient of AOPA’s Sharples Award, given for “the year’s greatest, selfless commitment to general aviation by a private citizen,” for flying humanitarian relief into Nigeria during the Biafra Civil War. He was also presented the prestigious Heritage of Freedom Award, and in 1987, the Experimental Aircraft Association’s highest honor, the “Freedom of Flight Award,” for his role in the organization’s “In Pursuit of Dreams” presentation.

Robertson’s affiliation with EAA began a long time ago.

“I pull a long bow, back over 30 years,” he said. “It was back in the days when it was at Hale’s Corners (Wisconsin). I had heard about this remarkable guy named Paul Poberezny and his lovely wife and their young son, Tom. So, I went back there. It was snowing. All we had was an indoor showroom, and she made us chili. It was a very simple operation. Now, you get almost a million people.”

Years after becoming involved with EAA, Robertson decided to give others the opportunity to feel the same way he did as a youth in La Jolla. Within EAA, he founded the Cliff Robertson Work Experience, in 1993.

“We have a contest where young people (at least age 16) submit their desires to come to Oshkosh and work for 12 weeks, in hangars, doing all the dirty work that we used to do as kids,” he said. “In exchange, they not only get their room and board and a little bit of allowance money, but they also get flying lessons. The work ethic is not dead yet. We’ve had wonderful success with it. Some of our ‘graduates’ have gone on to West Point and the Air Force Academy and some have gone on to fly with airlines. It’s been very productive.”

Robertson also helped launch EAA’s Young Eagles program, organized in 1992, serving as its first national honorary chairman, until 1995. At EAA AirVenture 2002, he was presented with the inaugural “Key to the City” Award, created by EAA and the City of Oshkosh to honor distinguished personalities for significant contributions to the promotion and support of EAA AirVenture Oshkosh and the aviation community.

There’s Nothing Purer

Robertson said that to name one form of flying as his favorite would be like naming a favorite child. However, he does say there’s nothing “purer than pure glider flight.”

“To be environmentally sensitive for a moment, that’s because you’re not burning fossil fuels and you’re not bruising or abusing the environment,” he said. “You’re working with nature, so there is purity there. There’s also a sense of pride that once you’re up there, you’re on your own. You don’t have an automatic pilot and if you go as I did, for six hours and 20 minutes, on that attempt for distance record, you have a sense of, ‘Well, I did something kind of special.'”

Robertson glides as often as he can, and does a little aerobatics, but says it’s “nothing to write home about.”

It’s not unusual for the resident of Water Mill, Long Island, N.Y., and La Jolla, to fly across the country. When he needs to get somewhere in a hurry, he takes one of the “big aluminum tubes.” However, when he’s not in a hurry, he prefers flying his twin-engine Baron, which he’s had for over 20 years, because he can give himself two days, taking time to stop along the way at “a little pokey airport” to reacquaint himself with his country. He happened to be flying the Baron on Sept. 11, 2001.

“I was the only guy flying right over that holocaust, at least that I know of, when it all happened,” he said. “I was flying alone, on the way to the West Coast. I got right over the World Trade Center, climbing at 7,000 feet. I looked down and suddenly saw this great big column of smoke puff up. I didn’t see the plane, because by that time it was inside the building. I just thought it was an explosion of some kind.”

Robertson said that after he had climbed to 8,500 feet, and leveled off, the other plane hit.

“Again, I didn’t see what caused it, but the air traffic controller came on and I gave my call number,” he said. “They said, ‘We have a national emergency. Land at the nearest available airport.’ I’d never heard that in all the years I’d been flying. I was hermetically sealed for three and a half days in beautiful downtown Allentown. I couldn’t take my plane out. I finally got out on a commercial flight. Later, my buddy Craig McCaw had one of his pilots, who was out on the East Coast, fly the airplane back to me. I was up giving a talk at an aviation conference in Oregon.”

The Ups And Downs Of Hollywood

Robertson laughs and says he still recalls the plays in elementary school, where children aspired to don costumes for stints as vegetables and fruit—something he wasn’t inclined to want to do. He also remembers his third-grade teacher telling him that acting was “a dodge.”

“I still think it’s a dodge,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t put his heart into whatever role he lands. He received an Emmy for Best Actor for a guest appearance for the Bob Hope Chrysler Theater’s “The Game.” Three years later, with ABC Pictures, he co-produced “Charly,” at the modest cost of $1 million. His intense performance earned him the 1968 Oscar for Best Actor, over nominees Alan Arkin for “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,” Alan Bates for “The Fixer,” Ron Moody for “Oliver!” and Peter O’Toole for “The Lion in Winter.”

At the time the winner was announced, Robertson, who didn’t think he had a chance, was over 7,000 miles away, in his trailer in the Philippine jungle, working on “Too Late The Hero.” He said he wasn’t even listening for the announcement, but Michael Caine and several other fellow actors were hovering over a short-wave radio outside. Caine soon burst into the trailer, exclaiming, “You won the damn award!”

Robertson thought he was joking. Later, someone with a camera took a picture of him being thrown up in the air in celebration, in his military outfit and Scottish tam, and it was sent around the world.

Even with winning an Oscar for “Charly,” Robertson says he’s never been fully satisfied with his Hollywood career—or with any of his other achievements, for that matter. He says he has been “reasonably” satisfied, but it could be better stated that he looks at his accomplishments with “a degree of dissatisfaction,” and, when it comes to his movies, he is “less dissatisfied with some than others.”

“You always feel like you could do better if you could do it over,” he said. “Once you cross the Rubicon of a certain age, you don’t get satisfied, but you get a little more mature. You say, ‘I guess I did the best I could, given what I was given’—and given the time limitations and some of the questionable characters you’re working with.”

L to R: Jerry Lips, Di Freeze, Cliff Robertson, Dick Hansen and Paul Lips at Centennial Airport, headquarters for Airport Journals.

Robertson said he was partial to “J.W. Coop,” released in 1971, which he co-wrote and directed, because he was able to write about something with which he was familiar.

“It was about a rodeo rider and man’s confrontation with change, which is the antagonist in everybody’s life,” he said.

Besides flying one of his Tiger Moths in the film, he also did some bull riding. He says his experience in that arena was “genetic.”

“On my father’s side, there were a lot of horse people going way back,” he said. “I think when you have a genetic predisposition it gives you kind of an ill-deserved confidence. I had an uncle who had a big ranch in Colorado, about 25 miles from Walsenburg, in a little town called Red Wing. He had 55,000 acres. It was unbelievable. It was beautiful, like a little Switzerland. I was married at the time and I’d take my former wife (actress Dina Merrill) and my two daughters out there in the summertime.”

Robertson had the chance to fly in other movies, including flying a DC-8 in “The Pilot,” which he directed, and taking to the air in “633 Squadron.” His film credits in the seventies included “Three Days of the Condor,” released in 1975, and “Midway,” released in 1976, in which Robertson appeared as a pilot in a bar scene that he wrote.

But the following year, his Hollywood career came to a temporary halt when he blew the whistle on David Begelman, Alan Hirschfield’s right-hand man at Columbia Pictures, in an embezzlement scam that became known as “Hollywoodgate,” after Columbia’s accounting department sent him a 1099 saying he owed taxes on money he never received.

“I hadn’t even worked for Columbia,” he said. “This old Scot’s not going to pay taxes on money he didn’t earn.”

After Robertson and his secretary began investigating the statement of earnings, a supervisor at Columbia looked up the Robertson file and found an endorsed check made out to him. However, the signature on the back wasn’t his.

“In spite of a lot of sage advice and people warning me, I went ahead and gave it to the FBI,” said Robertson.

Law enforcement agencies initiated further investigations. More improprieties came to light and Begelman “resigned.” For Hirschfield, the Columbia crisis ultimately came to a head at a July 1978 board of directors meeting, when the board voted not to renew his contract. However, Begelman and Hirschfield were soon back at work in one capacity or another; Robertson wasn’t.

“After they broke open Hollywoodgate, I was blackballed and didn’t work for three and a half years,” Robertson said. “They were trying to send a message to other would-be Don Quixotes. The FBI told me that the unwritten covenant in Hollywood for 75 years has been, ‘Thou shalt never confront a major mogul on corruption or thou shalt not work.'”

Even with that outcome, Robertson said he’s proud of what he did.

“They wrote me up in that congressional record,” he said. “I was given a lot of citations. All the writers and the creative people were delighted.”

Within two years, several other actors began confronting corporate corruption and “creative bookkeeping.”

The curse on Robertson was finally removed when a “courageous director” named Doug Trumbull cast him in “Brainstorm,” Natalie Wood’s last film.

“He said he wouldn’t listen to those bastards,” Robertson said. “He said, ‘He’s right for this role and I’m going to hire him.’ As soon as he did, it broke the cycle.”

Over the last 15 years, Robertson has appeared in several films, including “Dead Reckoning” (1990), “Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken” (1991), “Escape From L.A.” (1996), “Family Tree” (1999) and “Falcon Down” (2000). More recently, he played Uncle Ben Parker in “Spider-Man” (2002), and although his character met a sad demise, returns in “Spider-Man 2,” opening in early July. He recently completed Steven King’s “Riding the Bullet,” which is his 72nd feature film.

“I have many friends in Hollywood, but I don’t live in LaLa Land and I don’t embrace the lifestyle or network, so I probably don’t get some of the things done I’d like to get done,” he said. “I prefer living in the country away from some of the glitz. I’m happy to run out here, spit out the words, pick up the check and run, to go back to my cat (“Halsey”) and make apologies.”

He adds that he’s never found it necessary to throw away money on press agents.

“My former wife had them on both coasts,” he said. “She used to say, ‘You’re nuts. You’re an Emmy Award winner, Oscar winner and stage winner; you should have a press agent.’ I said, ‘Nope. Work begets work, and I’m not going to pay a lot of hard-earned money to get my name in a column. I’d rather give it to charity.'”

Playing Hooky

Robertson says he’s always been obsessed with working. For instance, when he was 10, he lied and said he was 11, to get a job selling magazines.

“I had a newspaper route and then I had a little skiff,” he said. “I’d get up in the morning and go out and get my lobsters, at 5:30 in the morning.”

One of the reasons for his obsession is that his father was “to the manner born.”

“He never worked a day in his life,” he said. “I mean, he did a lot of things, but he never worked.”

Robertson attributes his “work-instilled ethic”—as well as his contributions to myriad charities—to “Calvinist guilt.”

“I was brought up Presbyterian,” he said. “A lot of the old verities still hang in. You know, when you’re a very young dude, you kind of wander away and think you have it all figured out. You flirt with being agnostic, atheist or whatever. Then, when you’ve been around the pike a few times, certain things begin to stack up, and you think that maybe some people had it right.”

Having a Calvinist conscience, says Robertson, also gets in the way of taking himself too seriously. To be Calvinist, explains Robertson, isn’t as simple as believing in predestination, or that all has been planned.

“That’s not quite right, but that’s part of it,” he says. “There is a pattern. But the kind of perverse aspect is, ‘If the medicine tastes good, it can’t be good.’ If it tastes bad, it has to be good!’ It’s a perpetual ‘hair shirt,’ but it does kind of give you a work ethic, and kind of a good ethos.”

Although a hard worker, Robertson takes the time to “play hooky,” which could mean his annual visits to EAA AirVenture, or traveling with Hilton to Alaska to fish. He’s a regular visitor, along with others, such as Carroll Shelby.

“Barron flies us up in his Citation,” he says. “We go up there regularly in the summer, and sometimes in late spring. We all go fishing on Barron’s boat.”

Besides everything else he devotes his time to, Robertson speaks around the country, through the Aviation Speakers Bureau. Although he has plenty of aviation stories to tell, he also draws from his Hollywood experiences.

“When you’ve done 72 films, you have a lot of stories,” he said. “I have stories about movies, my own exploits, other famous actors—and not famous actors. There’s a wide matrix of subject matter.”

Robertson is writing a sequel to “Charly,” and enjoys writing essays, both serious and humorous. He has indeed collected a lifetime of stories, many that will appear in an upcoming book, due out next year. Prior to that, we’re happy to say, several will appear in Airport Journals, in Robertson’s new column, “Cliffhangar.”

To book Cliff Robertson as a speaker, call the Aviation Speakers Bureau at 800-247-1215.