By Stan Sears

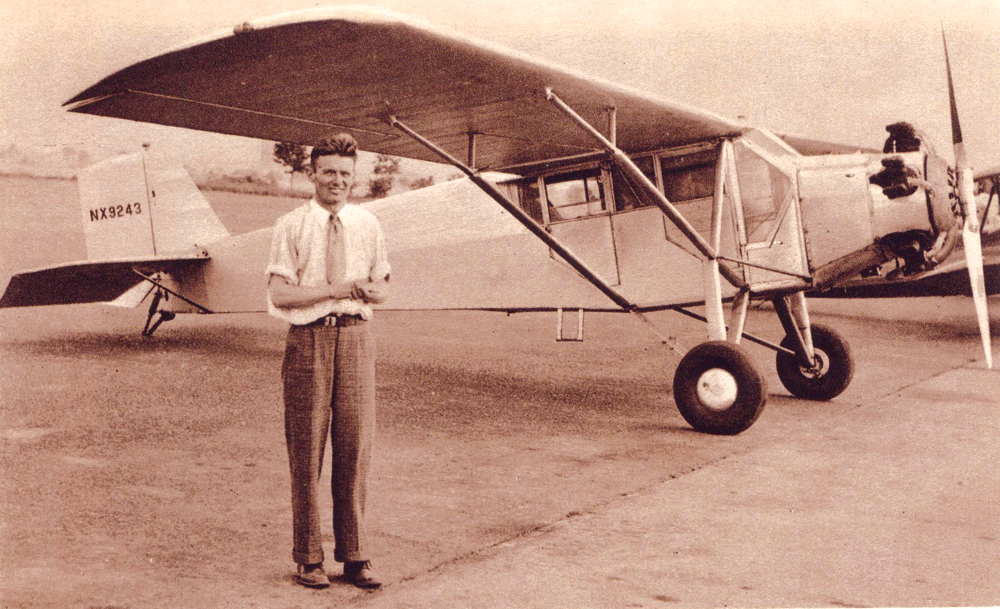

Douglas Corrigan and the Curtiss Robin at Roosevelt Field in New York in 1938, a few days before his famous transatlantic flight.

He’d been up all night, waiting. He’d wanted to take off at midnight, but because of a persistent fog on this summer night, July 17, 1938, permission didn’t come until 4:00 a.m. Actually, he’d been waiting three years for this flight-—longer, if you counted the moment the idea first entered his head. A few hours more at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn wouldn’t matter.

In truth, the thought of some sort of great air adventure probably was born during 18-year-old Douglas Corrigan’s first ride in an airplane back in October 1925. He was instantly captivated by the thrill of flying and became an apt student, learning quickly; he soon became a proficient pilot. He was also an expert welder and aircraft mechanic; there wasn’t much that could be done with an airplane that he hadn’t accomplished, or many hazards that he hadn’t experienced-—and survived. Somewhere deep inside, he felt he was destined to accomplish some great feat of flying.

This vague vision took on a more definite shape the day he met Charles Lindbergh for the first time. Lindbergh had come out to Ryan Airlines in San Diego in February 1927, looking desperately for an aircraft that he could fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Corrigan had been working there as a mechanic, and was proud to shake the hand of his new hero; he was equally proud to help with the construction of the new Ryan NYP that would be named “Spirit of Saint Louis.”

Ready

It was finally time to get started. His Curtiss Robin had been fueled up and wheeled out of the hangar. After cranking the prop to start the engine, he walked over to thank the field manager for his help and asked in which direction he should take off for the return trip west to California.

He was told that other than avoiding the buildings on the west side of the field, the direction didn’t matter. With hardly any wind to consider, it was an easy decision: he’d take off to the east. The fuel-laden plane used up 3,000 feet of runway before finally leaving the ground, and had gained only 50 feet of altitude when he cleared the eastern edge of the runway. Knowing that the plane would not climb very fast, he decided to fly straight ahead to the east for a few miles before turning west.

When he reached 500 feet, the ground was still obscured by fog. As he began his turn to the west, he noticed that the compass on the instrument panel wasn’t working, due to the liquid having leaked out. Untroubled, he simply used the auxiliary compass mounted on the floor of the plane, continuing his turn until the magnetic needle indicated that he was on a preset “westerly” course. He settled in for the long cross-country flight, as calm as if he’d done it all before. In fact, he had-—seven times—although a couple of them had been “unofficial.”

1933

Corrigan purchased the used, OX5-powered Curtiss Robin in New York in 1933, and flew it back to California with his brother, Harry, stopping every hundred miles or so “to hop a few passengers.” The journey back was an adventure in itself, featuring a few accidents and several ingeniously-contrived stopgap repairs.

For the next two years, he worked at several jobs as a mechanic and pilot, but he wasn’t happy. He finally decided to enable the dream that had been gestating in his mind ever since Lindbergh had made his successful Atlantic crossing. He would install a larger engine and extra gas tanks in the Robin and seek permission for a solo, non-stop flight from Newfoundland to Ireland.

However, the chief inspector in Los Angeles would only approve the larger engine, saying he’d let Corrigan know later about the tanks. Disappointed but hopeful, Corrigan purchased and installed a 165-hp Wright J6-5 engine and made a complete overhaul of the plane, including all new fabric covering.

Nevertheless, without an unconditional approval of his plane for long flights, he was at the lowest point of his life. With nothing else to do, he began work on the large, auxiliary oil and gas tanks he would need for the overseas flight. If he didn’t receive permission, he thought, he’d “punch holes in the tanks and throw them in the bay, with me and a big rock tied onto the tanks to make sure they didn’t float.”

August 1936

One afternoon in August 1936, with the Curtiss Robin finally licensed for cross-country trips, Corrigan impulsively decided to fill the tanks and take off from Lindbergh Field in San Diego, headed for St. Louis. Like most small aircraft of the day, the Robin had only the most basic flight instruments, with no flight attitude indicators and no radio.

His only navigational aids were a few maps, a magnetic compass, and his wits. He made it to St. Louis, and then flew on to Roosevelt Field in New York, but only after a harrowing three days of severe storms and engine problems, none of which affected his transatlantic ambitions in the slightest. In fact, that was only the beginning of his cross-country flights.

In October of that year, he made a return trip to California. Having fueled up with 225 gallons of gasoline, he landed 19 hours later at San Antonio, Texas, a trip of 1,900 miles, the same distance—not coincidentally—-as a flight from Newfoundland to Ireland. He then flew nonstop to California, having satisfied himself that he could carry enough fuel to cross the Atlantic, in a plane that could handle all the trouble nature could dish out. A round trip to New York and back also looked very good in his logbook, although it didn’t stem the urge for something bigger.

Summer 1937

In the summer of 1937, Corrigan applied for permission to fly from New York to London, but following the tragedy of Amelia Earhart’s disappearance, all licenses for solo transatlantic flights had been cancelled. But the urge for some sort of long distance flight was unbearable, so he made a daring decision. He would make an unlicensed cross-country round trip. Looking on a map, he found an airfield in Brownville, Maine, and headed out for it. Again using only his compass and his wits, and landing in small out-of-the-way places after dark-—not always airstrips—-he made it to Maine and back safely.

He had now logged his second coast-to-coast round trip, although it was one that he couldn’t tell officials about. But it still wasn’t enough; he wanted a crossing to Ireland. Emboldened by his successful sneaky round trip, he made the most audacious decision yet.

“Why not land at Floyd Bennett Field some evening after the officials had gone home, and fill up with gasoline and go?” he thought. “They can’t hang you for flying a plane without a license.”

So he set out again for New York, intending to fly from there to Newfoundland. Perhaps he would have ultimately made it all the way to Ireland except for one thing. It was October.

Douglas Corrigan next to the Curtiss Robin at Roosevelt Field in New York in 1938, shortly after completing his nonstop solo flight from Long Beach, California.

That trip to New York was the worst that Corrigan had ever made. He was forced down by bad weather each of nine consecutive days in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas (twice), Arkansas, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and finally New York. It was the end of a very cold October, with temperatures below freezing every night in New York, and all day long in Newfoundland. So he turned around and flew back to California, enduring more freezing temperatures, headwinds, icing and an overheating engine.

Once again, all of this was accomplished while having only a compass to find his way. By the time he reached California, he had no water and had eaten only one sandwich in the three days since leaving New York. At Adams Airfield, an inspector saw his plane and forbade him to fly it. For once, Corrigan was agreeable; he’d logged round trip number three, and had no further plans for flying. Not, that is, until the next summer.

Summer 1938

In the summer of 1938, the itch was back. Corrigan wheeled the Robin out of the hangar at Adams Field in California for the first time in six months and gave it another complete overhaul, after which he received his first license to make a nonstop cross-country trip to New York. If he succeeded, he would be permitted to make a return nonstop flight, a round trip for which he could finally take credit.

On July 7, 1938, he put one hundred gallons of gasoline in the Robin’s tanks and told everyone he was headed for Texas. Then he flew to Long Beach, Calif., added another 145 gallons, telling everyone there he was headed for El Paso. Therefore, no one at either field knew he had enough fuel to fly all the way across the country.

Of course, he was actually on his way to New York for the first leg of his grand adventure, but for now he wanted to keep it a secret, in case he failed. Once again he had a dangerous and exciting flight to New York, this time with no opportunity to set down anywhere along the way without ruining the nonstop status of the trip.

Twenty hours out of Long Beach, after flying all night, he ran into vicious storms over the Cumberland Mountains in Tennessee. He flew under the clouds, twisting and turning up through the valleys a mere hundred feet above the trees until he saw clouds ahead that reached the ground. Then it was full power and up through the clouds, where he was forced to fly along between cloud layers for an hour, seeing neither sky nor ground, doggedly following a compass course.

To add to his problems, the main gas tank began leaking, adding noxious fumes to his problems. Nevertheless, he made it to Roosevelt Field in New York at sundown on July 9, landing and rolling to a stop in front of a hangar with only four gallons of gasoline remaining. It was a most remarkable feat of piloting and navigation.

Corrigan was elated. His successful coast-to-coast, nonstop solo flight-—still a rarity in 1938-—might earn him some headlines, but most important was the fact that he had now earned the right to take off and make the return trip to California.

Finally

During the first couple of hours of the flight out of Floyd Bennett Field, he glimpsed an occasional tree through holes in the fog, and then passed over a city he decided was Baltimore, Md. Retrospection would later show that it was actually Boston, Mass.

That’s the last he saw of anything but clouds for the next few hours. At eight hours out of New York and 4,000 feet of altitude, the clouds were just below his wheels. At 10 hours out, he joked to himself, “Douglas, you’ve got cold feet.”

He wasn’t frightened, of course, but he did have a problem. The cold on his feet was from the evaporation of aviation gasoline; a leak in the main fuel tank was dribbling fuel onto his shoes.

The leak had actually started during the flight from California to New York. Characteristically, it hadn’t worried him then, and it didn’t worry him now, although—-for the sake of thoroughness—-he wished he’d had time to repair it. But, he figured he’d be past the clouds in a few hours, and could land anywhere if the gas ran out. He was at 6,000 feet, and with clouds still above and below, he couldn’t see the horizon, and would have to fly on instruments. That meant using the compass to stay on course, and the turn and bank indicator and throttle settings to maintain straight and level flight.

At 15 hours out of New York and still flying straight and level, it got dark, and the leak in the tank became worse. Using a flashlight, he saw gasoline an inch deep under the floorboards. The engine exhaust pipe was located right outside the left-front corner of the cockpit floor. To prevent any gasoline from leaking out and hitting the exhaust (with disastrous results!) he simply took a screwdriver and punched a hole in the bottom skin of the fuselage at the right- rear corner of the cockpit floor, where the fuel would run out harmlessly. Harmlessly, that is, as far as any fire danger was concerned. However, there was now the critical problem of fuel consumption.

Corrigan’s situation made an interesting puzzle for student pilots. He had to weigh the rate of fuel loss from the leak, which he couldn’t control, against the consumption of fuel by the engine, which he could. The latter involved a trade-off that had to be carefully evaluated.

“If I run the motor slow, the gasoline will have more time to leak out, so I’ll run the motor fast and use the gasoline up before it leaks out,” he reasoned.

To accomplish this, he increased the engine speed from its cruise setting at 1,600 rpm to the full-power setting at 1,900 rpm, trusting the engine would last. And why shouldn’t it? After all, over a period of time, he had practically rebuilt the entire engine twice over.

Still flying at full power the next morning, Corrigan saw that the clouds out in front were piled up to 15,000 feet. That was higher than he wanted to fly, so he proceeded directly into them at 8,000 feet, flying on instruments for the next two hours through torrential rain.

Then it began getting colder; concerned about icing up, he flew lower, expecting at any moment to see mountains peaks poking through the clouds. He dropped out of the clouds at 35,000 feet, but instead of mountains, he saw water in every direction. This was strange. He’d only been flying 26 hours, not long enough to have reached the Pacific Ocean, so what had happened? He looked down at the compass on the floor; now that there was more light, he noticed that he’d been following the wrong end of the magnetic needle for the entire flight, and had been flying east!

The man who had flown across the Unites States seven times with only a compass and his wits for navigating had been following the wrong end of the compass needle? He was somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean, but where? He decided to keep flying east, and soon saw a small fishing boat. He couldn’t help but think of Lindbergh, who had also spotted a small fishing boat on his solo flight. In fact, he’d been thinking about Lindbergh the entire flight.

Corrigan knew he could not be far from land, and it had to be Ireland. A few minutes after passing the fishing boat, Corrigan saw “some nice green hills ahead of the plane.”

Ireland! He needed to find out exactly where in Ireland he was, so he flew inland for about 45 minutes until he had crossed to the eastern coast, where he turned south. After another 40 minutes or so, he passed over a large city, and spotted an airport off to the right, with the name “Baldonnel” marked in the center of the grass field.

The city was Dublin, home of his ancestors. Like any good pilot, he circled the field twice, checking traffic and wind direction, and then made a perfect landing. He taxied up to the flight line and got out of the plane, leaving the motor running—in case he wasn’t welcome. He walked over to an Army officer who had just come out of the field office, and said, “My name’s Corrrigan. I left New York yesterday morning headed for California, but I got mixed up in the clouds and must have flown the wrong way.”

Neither the Irish officer, the Irish people, the English people, the people of the United States, nor most of the people in the entire civilized world ever chose to doubt that winning explanation. They hailed a hero.

Nor did Douglas Corrigan ever give them a reason to change their minds. He wrote a book about his life and the flight, and the book’s somewhat defensive title seems to anticipate the possibility of skeptics. He named the book “That’s My Story,” and it was a story he stuck with for the rest of his life.

It was one of the great stunts of the Twentieth Century, shared with a smile and a wink by a Depression-weary American public that welcomed this sort of adventurous diversion. Ireland and England greeted him with open arms, introducing him to officials, dignitaries, royalty and throngs of citizens.

Back in the United States, he was treated as a national hero, meeting dozens more famous and important people, including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Corrigan made a flying tour of the country, and was given parades and feted by mayors, governors and masses of people in every city and state that he visited. Most major newspapers and radio broadcasts in the world carried the story of his “accidental” solo Atlantic crossing, accommodating his good-natured explanation by dubbing him “Wrong Way” Corrigan. Most of the hundreds of gifts he received were compasses.