By Bob Shane

“Operation Babylift” adoptees pose with former World Airways chairman of the board Hollis Harris (left), World Airways CEO Randy Martinez (second from left), and General Ronald Fogleman (USAF ret.), World Airways chairman of the board (right end).

The Vietnam War ended on April 30, 1975, with the fall of Saigon. During the weeks leading up to this climactic event, humanitarian organizations were anxiously looking for ways to evacuate the thousands of orphaned Vietnamese children that the conflict had produced.

On April 2, 1975, Ed Daly, World Airway’s maverick president and owner, in what most regard as a heroic act, departed Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon aboard a DC-8 cargo aircraft carrying 57 orphans headed for Oakland, Calif. This flight was the first of a series of flights, which became known as “Operation Babylift.”

In April of this year, World Airways announced that it would commemorate the historic airlift that the company made 30 years ago with a special flight that would return 21 of the former orphans for a visit to the country of their birth.

It was 1 p.m. on June 12, when a shiny World Airways MD-11, freshly re-painted in the same red and white company colors worn by the fleet in 1975, landed at Oakland and taxied to the KaiserAir ramp. World personnel immediately began the process of getting the aircraft ready for the start of “Operation Babylift—Homeward Bound 2005.”

That evening, there was a reception held at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. The invitees included everyone that would be departing on the special flight the next morning, World employees and retirees, and the media.

The next morning, just prior to departure, there was a press conference at KaiserAir across from Hangar 5, which was World Airways’ original hangar when the company set up operations in Oakland in the 1950s. Steve Grossman, director of aviation for the Port of Oakland, began his speech by welcoming World Airways home. Randy Martinez, the CEO of World Air Holdings stated, “We’re here to honor our heritage and recognize the contribution of our employees.”

The passenger manifest for World Airways Flight #001 contained 112 names, several right out of 30-year-old newspaper headlines. Included were pilots, flight attendants and other World personnel that had risked their lives to save orphan children and refugees. There were decorated Vietnam veterans and distinguished members of World’s board of directors, management team and their guests.

Then of course, there were the special 21 orphans that were the focus of Operation Babylift. A modest press contingent accompanied the group to cover what for many would be an emotional experience. For a journalist such as myself, this was a great opportunity to meet the faces behind the headlines. It was exceptional to be able to travel back to actual locations where history was made and be able to relive history through the eyes and minds of those that made history!

For those on board, the trip would answer many personal questions; for some it would fulfill a solemn promise made a long time ago. Many new friendships would be forged. Everyone, without exception, felt this would be the trip of a lifetime.

Following the press conference, the passengers boarded the World Airways MD-11. Sitting on the ramp at Oakland, the jet airliner was stunning in its newly applied retro paint scheme. In fact, it looked so good that when CEO Martinez first saw the airplane, when it was being painted by Delta, he commented, “We’re in trouble. When the employees see it, they’ll want us to paint them all.” Inside, the aircraft was configured for 291 passengers, made up of 24 first class seats and 267 coach seats. The flight crew consisted of four pilots and 12 flight attendants, who provided an exceptional business class food service.

Right on schedule, at 10:45 a.m., we were racing down the runway at Oakland. Captain Franklin dipped the left wing as we passed near San Francisco, heading out toward the Pacific. Once off the California coast, the aircraft was established on a heading that would take us close to Adak, Alaska, where we would then pick up Airway NP220, the most northern standard route to Asia. Next stop Taipei.

After a story-filled 13-hour flight to Taipei, Taiwan, we landed at Chiang Kai Shek International Airport where the aircraft was ground handled by Eva Air, one of World’s customers. The stop would be overnight, making it an opportunity to rest up for the next day’s visit to Ho Chi Minh City, or if you prefer, Saigon.

Upon arrival in Ho Chi Minh City, there was a press conference held in a VIP room inside the Tan Son Nhat airport terminal. Vietnamese officials, including the deputy mayor of the city, were in attendance. After breezing through immigration, the group boarded modern tour buses and headed downtown to a brand new Sheraton Hotel. Less than two years old, it was perhaps the finest hotel in the city, with service standards comparable to any Sheraton in their worldwide system. The hotel is characteristic of the economic boom that Vietnam is now enjoying as a result of the U.S. lifting what remained of its trade embargo in 1994.

The next day’s schedule included a tour of the city and an orphanage run by catholic nuns, a boat ride on the Saigon River, and the finale, a gala dinner at the Presidential Palace, which is now the Reunification Palace. During the evening event, Shirley Peck-Barnes, author of the book, “The War Cradle,” which documents Operation Babylift and its legacy, presented a quilt she made to our Vietnamese hosts. It was a special quilt in that it was made from the baby clothing worn by the orphans when they left Vietnam in 1975. Additionally, it was signed by the passengers traveling on the World Airways commemorative flight. Today, the palace is a museum and is used for receptions and special events. For me, it still remains a symbol of the end of the war. I’m sure we all remember the picture of a North Vietnamese tank smashing through the fence and entering the grounds of the palace.

The next morning, motor coaches transported the group back to Tan Son Nhat Airport for the 14-hour, non-stop flight to San Francisco. It was another opportunity to hear more war stories and learn of the adoptees’ impressions of the country of their birth.

The first Babylift flight

Pilots Bill Keating and Ken Healy flew the original Operation Babylift flight from Saigon on April 2, 1975, and were honored guests on the commemorative flight. Their accounts of that historic flight and other flights they made during the final weeks of the war read like a Hollywood script. Keating is now 90 years old and Healy is only six months his junior. While they both had major roles in shaping historic events, the central protagonist was Ed Daly.

Daly was the colorful non-conventional president and owner of World Airways. It was rumored that when he acquired the airline in 1950, he paid for it with $50,000 in poker winnings. Often characterized as a combative, hard drinking, pistol-packing Irishman, he also had a generous side. Operating in a war zone, the tough-talking Daly wore a safari suit with a green beret or a bush-styled hat and always carried a 38 caliber pistol. He enjoyed flying around the world in his two private aircraft, a B-23 once owned by Howard Hughes and a Convair 440 painted in 14 different shades of green, with a shamrock on the tail and a leprechaun painted next to the entry door. Daly called his Convair the “Jolly Green Giant.”

Of the tens of thousands of Asian refugees that immigrated to the United States following the end of the Vietnam War, the most dramatic evacuations involved orphaned babies and abandoned children. During the final weeks of the war, humanitarian organizations were asking the U.S. government to formulate a program for the evacuation of Vietnamese orphans. Despite these pleas for help, nothing seemed to be happening. The process was completely entangled in a sea of bureaucratic red tape. Something significant needed to happen to break the stalemate.

On April 2, 1975, the 52-year-old Daly made the extreme decision to use one of his DC-8s to airlift orphaned children out of Saigon. World had been using their DC-8s on the rice lift, flying rice from Saigon to Phnom Penh in Cambodia. The pilots wore helmets and flack jackets because the field at Phnom Penh was always under fire.

Normally, the ground time was 11 minutes to unload 100,000 pounds of rice; the crew always kept the number three engine running. During one trip Keating made into Phnom Penh on March 5, 1975, the aircraft was hit by a 105-mm round while it was unloading rice. Thinking the aircraft was disabled, the USAF ground officer informed Keating that the aircraft would have to be moved out of the way and be destroyed.

“I have a little bit of a problem with that,” Keating stated. “Mr. Daly wouldn’t like that!”

Keating inspected the aircraft. While the hydraulic system was damaged, the fuel system was OK, so Keating decided the aircraft was flyable and flew the DC-8 back to Saigon with the landing gear down. The aircraft was later repaired.

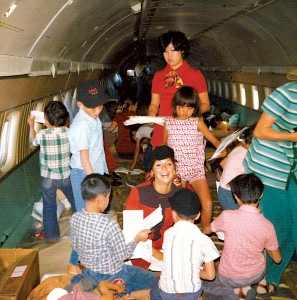

World Airways flight attendants Carol Shabata (standing) and Valerie Witherspoon (kneeling) play with the Vietnamese orphans on the historic evacuation flight on April 2, 1975.

Keating would be the captain on the first leg of Operation Babylift from Saigon to Yokota Air Base in Japan. Captain Ken Healy would fly the Tokyo to Oakland leg. As the day progressed, it didn’t appear any progress was being made. Neither the South Vietnamese nor U.S. governments sanctioned Daly’s flight. For one thing, the DC-8 was configured for cargo and it had no seats. They were telling the various organizations wanting to evacuate children that the plane was unsafe.

Ross Meador, the 20-year-old co-director of overseas operations for the Friends of Children of Vietnam, came out to the airport to meet with Daly. Meador hoped to get some of the orphans in his care on the flight to Oakland. Daly offered to take the children, but the main concern was whether the South Vietnamese government would let them leave.

It was early evening and there were rumors that the Viet Cong might attack the airport. Daly had Meador contacted, advising him that he was going and Meador needed to get the children out to the airplane. The orphans arrived at the DC-8 singing a new song that Meador had taught them in route to the airport, “California here I come.”

The floor of the DC-8 cabin, covered with blankets, pillows and cardboard, would soon be a giant playpen in the sky. South Vietnamese soldiers came aboard the DC-8 and took off two of the orphans who appeared to be at least 14 years old and consequently eligible for service in the Army. Daly tried to buy the children with a hundred dollar bill, but the soldier wouldn’t take it. Jeff Gahr was one of the orphans on the flight; it was his brother Jason that the soldiers removed.

“I didn’t know if I would ever see my brother again,” he stated.

Daly tore the bill and gave Jason half as a souvenir. He did make it to the U.S. on one of the subsequent evacuation flights. All these years, he kept the souvenir. He had it laminated, and brought it with him on the commemorative flight.

The first Operation Babylift flight took off from Saigon in darkness; the airport had turned the runway lights off. The DC-8 departed without a formal clearance to take off or a flight plan filed. Daly paid for the flight out of his own pocket.

Jan Wollett, one of the flight attendants on the original flight, seems to remember it as if it were yesterday.

“As we approached San Francisco, it was a perfectly clear night,” she said. “It seemed like every light was turned on.”

As some of the orphans looking through the aircraft windows shouted, “America, America,” Wollett began to cry.

After landing in Oakland, the Red Cross came on board to take the children.

“Thank God we did it,” Wollett then said. “Thank God Mr. Daly had us do it!”

The next day, April 3, President Gerald Ford declared Operation Babylift a national initiative. Using mostly military aircraft, 30 flights were planned to evacuate orphaned babies and children. On April 4, the first authorized flight was attempted from Saigon using a C-5A Galaxy.

Twelve minutes into the flight, disaster struck. The aircraft was climbing through 23,000 feet when it experienced explosive rapid decompression. The rear ramp and pressure door blew out, severing all of the elevator control cables to the tail and disabling two of the aircraft’s four hydraulic systems. While trying to return to Saigon, the aircraft crashed in a rice paddy. Of those on board, 138 perished and 176 survived. Subsequent military flights were flown using the C-141 Starlifter.

The last flight From Da Nang

During the final weeks of the Vietnam War, thousands of refugees tried to escape from Vietnam and the advancing communist troops coming from the north. In Saigon, Daly heard that there were refugees roaming around the airport in Da Nang. He told World Airways pilot Ken Healy that he was thinking of sending a couple of Boeing 727 passenger planes up to Da Nang, to evacuate refugees.

So, on March 29, 1975, Healy and Daly departed Saigon for Da Nang. Healy talked to the tower before landing and was advised that the airport was peaceful. However, once on the ground and taxiing to the ramp, the aircraft was mobbed, mostly by deserting South Vietnamese soldiers who were dressed in civilian clothing. The officers had fled, leaving the young enlisted men to fend for themselves. Healy kept all three engines running as Daly blocked the rear entry stairs, trying to stop the soldiers and pick up women and children. Men driving trucks, cars, jeeps and motorbikes chased the 727, desperate to get on the aircraft.

Overhead, an Air America helicopter pilot advised Healy over the radio that the runway was blocked with vehicles and he needed to take off on the taxiway, which was 7,000 feet long. A newsman that had gotten off the 727 had to be left behind because the crowd pushed hum out of reach of the plane. Healy asked the Air America pilot if he could pick him up later.

A grenade went off, damaging the left wing, and the plane had to dodge bullets as angry men left behind fired at the plane. As the airliner started its takeoff roll on the taxiway, soldiers climbed into the luggage compartments, leaving the doors open. The rear stairs were damaged and couldn’t be raised all the way. Fuel lines had been hit and the aircraft was leaking fuel. As Healy continued his takeoff roll, he realized that he would have to go around a vehicle that was parked on the taxiway in front of him. A quick detour through the grass and he was back up on the taxiway with everything fire-walled for the balance of the takeoff. He pulled back on the control column, but the nose wouldn’t come up.

“I waited until there was no pavement under me then gave the controls one last pull,” he said.

The stick shaker went off as the plane finally rotated and started a slow climb. Several men clinging to the open stairs fell to their death. At least one person was crushed in the wheel well doors. The flight to Saigon was flown at low altitude. Captain Healy, not knowing the conditions of the landing gear, carefully put the 727 down on the runway.

The plane, which normally carries 125 passengers, had a total of 268 in the main cabin. Additionally, the cargo compartments were full of stowaways. It’s estimated that the last flight from Da Nang carried over 330 people—undoubtedly, the world record for the number of passengers ever carried on a Boeing 727.

Subsequent to the commemorative flight World made in June 2005, I met Wayne Lannin, a helicopter pilot for HTS Helicopters. During our discussion, I discovered he flew helicopters for Air America in Vietnam from 1970 to 1975. Amazingly, he was the pilot Healy talked to on the radio during his ordeal, while on the ground at Da Nang.

On that day, he was operating a Bell 204.

“We had been working on getting embassy people out of Da Nang,” he said.

Orbiting over the airport, Lannin had a unique vantage point. He watched the World 727 land and head for the ramp.

“What happened next was like a bad movie,” Lannin said.

He saw the aircraft being mobbed and people being blown away by the jet blast as they tried to stop the plane.

“I told the pilot, ‘Don’t go to the runway; they’ve got you blocked. Go to the taxiway,” he recalled.

He watched as Healy started his takeoff down the taxiway, went around the vehicle, and then went off the end of the taxiway into the red laterite dirt, sending up a huge cloud of dust.

“I thought he was history, when all of a sudden I saw him rising up out of this cloud of dirt,” he said. “My last radio transmission to the 727 was ‘Nice job, World!’ It went unanswered.”

Operation Babylift pilots Ken Healy (left) and Bill Keating (right) on the flight deck of the MD-11 that made the commemorative trip back to Vietnam.

When Healy and Lannin got together recently to discuss events of that historic day, Healy thanked Lannin for the assistance he rendered and for going back and rescuing the newsman left behind. It wasn’t until now that Healy knew that the newsman had been rescued.

An opportunity to say thank you

Seven members of the original crew were on board the World Airways Operation Babylift commemorative flight. Of the 21 orphans that made the journey back to Vietnam, five were on the first babylift flight. Many of the orphans took the opportunity to say thank you to the people that evacuated them from Vietnam.

Jeff Gahr, who spoke on behalf of the orphans at the press conferences and other formal gatherings, personally thanked the Americans for the love and care shown him 30 years ago.

“You opened up a world of opportunities for me that I never dreamed were possible,” said Gahr, who was adopted by an Oregon family and now works for Boeing as an electrical engineer in Seattle.

Flight attendant Atsuko, who crewed the original flight, always wondered if Jeff ever got together again with his brother Jason, after the soldiers had taken Jason off the flight. She was happy to find out that they were reunited.

Jennie Noone, who was evacuated on the last flight, sent a letter to President Ford in which she said, “Thank you for giving me a chance at life and for uniting me with a beautiful family.”

Jared Rehberg composed and recorded a CD that included “Waking up American,” which he dedicated to the birth parents he never met. Rehberg performed his song at the Reunification Palace.

Lana Noone’s first adopted Vietnamese child, Heather, died shortly after arriving in the United States. When she arrived at JFK Airport on April 23, 1975, she was very ill. She had been hospitalized a number of times and never weighed more than six pounds.

Noone made a promise to Heather that she would never be forgotten and that she would have a memorial service for her in the country of her birth. The commemorative flight enabled her to keep that promise.

Unanswered questions resolved

For a long time, Ross Meador, who put the 57 orphans in his care on the World Airways babylift flight 30 years ago, wondered if he had made a mistake.

“Maybe they would have been better off staying in their own country,” he said.

The commemorative flight has reinforced the feeling that his action probably saved their lives.

Vietnam vets return

Also returning to Vietnam—almost all of them for the first time—were a distinguished group of Vietnam Vets. On board the special flight was General Ronald Fogleman (USAF ret.), who flew 315 combat missions and is currently the chairman of World Airways. He put in two tours, the first in 1968 flying F-100s with the 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing, the “Buzzards of Bin Hoa,” and a subsequent tour flying F-4s. He was rescued after being shot down on Sept. 12, 1968, in an F-100.

Colonel Dennis “Bud” Traynor (USAF ret.) was the young Air Force captain and aircraft commander of the ill-fated C-5A that crashed on April 4, 1975, during the first military flight of Operation Babylift.

Lt. Col. James Dyer (USMC ret.) put in three voluntary tours of duty, one with the Navy, and two as an artillery officer with the Marines. Dyer also served in the Colorado State Legislature as both a senator and a representative. After departing Saigon, Dyer experienced a stream of tears, which he says was “a culmination of emotion from the whole trip.”

Capt. Bob Franklin, the command pilot of the MD-11 commemorative flight, was a Marine fighter pilot in Vietnam during the period of August 1969 to August 1970. He flew 275 combat missions in F-4s, while based at Chu Lai. For Franklin, visiting Vietnam was an opportunity to visit a country in transition.

“As we turned south on airway W15 from directly overhead Da Nang, I had a flood of memories flash from 35 years earlier,” he said. “The ‘popcorn’ cumulous clouds reminded me of the FAC’s (forward air controller’s) white phosphorous smoke marking targets. This was my combat area. To the west I could make out several landmarks in Laos, where we lost aircraft.”

He said his squadron alone lost nine airplanes during his year in combat.

“Below and to my left I saw the enormous Hoi An river valley where hundreds of missions were flown,” he said. “To my far left I could make out Chi Lai and the twin runways of the fighter base. My best thought was seeing a country at peace—wishing that if only the 40,000 people named on that granite wall in Washington, D.C. could see this nation, finally, after 30 years starting to embrace a number of the ideals for which they gave their lives.”

It would appear that time does heal all wounds, and in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the healing process has taken hold. The current Vietnamese prime minister has vowed to continue working on finding the remains of U.S. servicemen, and adoption between our two countries has been reopened. Even Nguyen Cao Ky, the flamboyant and colorful commander of the South Vietnamese Air Force, a prime minister and vice president, who spent his life in exile in California after the war, has returned to Vietnam, where he wants to live the remainder of his days.

A history of humanitarianism

Going all the way back to the airline’s inception, World Airways has a history of performing humanitarian missions. In 1956, its DC-4 aircraft airlifted Hungarian refugees to the U.S. More recently, it has flown relief flights in Bosnia and Somalia. Its philanthropic propensity has earned it a reputation as the “small airline with a big heart.”

Wherever there are trouble spots throughout the world, you will find World Airways on the front lines. It’s the largest carrier of U.S. troops. With a fleet of only 17 airplanes, it has managed to capture the lion’s share of the Defense Department’s business.

Following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, World was the first to operate a commercial flight into Baghdad. When the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan is secure enough, the airline will launch air service connecting Kabul with Washington, D.C. Humanitarian organizations like the Red Cross and the U.N. turn to airlines like World to transport personnel and supplies to the real hot spots where most other airlines won’t go.

Ed Daly may have passed away in 1984, but his “can do” spirit lives on at World Airways. The idea to do an Operation Babylift commemorative flight on its 30th anniversary mostly came from CEO Randy Martinez. It reportedly took two years of planning to make the flight happen; by the way, both the U.S. and the Vietnamese governments authorized it.

The management at World Airways is to be commended for having the resources and inclination to pay homage to their airline’s heritage, particularly being in an industry where survival is the full-time focus. It was a great flight and I’m sure that all 112 passengers will forever regard it as the trip of a lifetime.

Thank you World Airways!