By Ken Gaunt

William Ivy discovered the thrill of being a tightrope walker at an early age—about the same time he ran away from home.

Born in Houston, on July 31, 1866, he started parachuting in 1877, while working at the Thayer dollar circus—which would later be bought by PT Barnum—as a high-wire aerialist.

While working in a circus with Tom Baldwin and his brother Sam, William Ivy was asked to join the brothers in performing balloon ascensions. In order to become one of the “Baldwin Brothers,” in 1889, he changed his name to Ivy Baldwin, a name he would use for the rest of his life.

Ivy Baldwin’s height of 5 feet, three and a half inches, and weight of 120 pounds made him the ideal balloonist. It also helped that he had nerve, as evidenced by the fact that in about 1879, at Terre Haute, Ind., knowing nothing of balloons at the time, he filled in for a missing balloon crewmember.

“One of the regular men with the circus that used to make the balloon ascensions got drunk and didn’t show up. The manager asked me if I could go up and I did. After that, I took to ballooning,” Baldwin said in an interview in 1953.

The hot air balloons of that era were constructed of material much like a bed sheet. To fill the balloon with its needed amount of hot air, it was put over a stack at the end of a covered 15-foot trench in which a fire had been built. The fire’s soot would cling to the inner weave of the fabric, sealing the pores. The internal temperature would rise, as would the balloon.

It took 20 men to hold the balloon until it was ready to ascend. The ascent would slow to a hover at about 3,000 feet, as the balloon would cool. A typical balloon of this era used by the Baldwins held 25,000 cubic feet of air, and was 57 feet in height and 114 feet in circumference.

As spectators watched, suddenly, the balloon would go up—but one of the men would seemingly be caught in the ropes. That man was Ivy Baldwin. When the balloon reached altitude (approximately 2,500 feet) he would perform acrobatics on a bar, such as hanging by his knees or often by his toes. He would then turn loose of the bar, fall about 60 feet, pull a parachute out of a sack, and descend, hanging by his knees.

It’s believed that Ivy Baldwin made over 1,200 descents by parachute, and about 2,700 ascensions by balloon—in Canada, Peru, China, India and other countries.

In 1890, the Baldwins traveled to Japan to perform balloon exhibitions and parachute jumps. In addition to these feats, Ivy Baldwin also leapt from a 120-foot tower into a small net suspended about 10 feet from the ground. In Japan, he advertised his feat as a 150-foot jump. Japan’s laws were strict about truth in advertising, so Baldwin’s jump “would” be 150 feet. He later admitted that it was his only dive from that height.

When the emperor of Japan witnessed the feat, he was so impressed that he had a crew of his personal artisans sit up all night sewing Baldwin a presentation silk kimono, depicting figures of balloons and parachutes, as well as the harrowing leap, which would be one of Baldwin’s most prized possessions.

In 1893, Ivy Baldwin broke up the brotherhood, and moved to Denver, where he lived for the next 60 years of his life. There, on Sunday afternoons, he performed at Elitch Gardens, where he had first performed balloon ascensions, high-wire acts, and parachuting, at the request of John Elitch, in 1890, for the opening of the gardens.

Ivy Baldwin was known to say that his act was “the greatest poison in the world.”

“One drop could kill you,” he said.

The same year that he moved to Denver, the U.S. Army Signal Corps ordered a balloon made in France to beused for demonstrations at the World Fair’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago. However, the balloon arrived too late to be used before it was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas.

Captain Glassford, of the Signal Corps at Ft. Logan, near Denver, persuaded the Army to move the balloon there. In 1894, Baldwin was inducted into the Army as a Signal Corps sergeant combat observation section, to be in charge of piloting and maintaining the balloon.

When the craft was destroyed by wind in 1895, the Army reported there were no funds for the purchase of a new balloon. Baldwin persuaded the Army to make $700 available. Then, he and his wife Bertha cut and sewed a pongee silk balloon at their home. Baldwin covered the silk with varnish to make it air tight; with the rope webbing and basket from the original craft, the observation balloon was back in business.

The Army balloon was inflated with hydrogen, which was manufactured and compressed into tanks at the military post instead of the risky hot-air method.

Baldwin is credited for developing both methods. He told about his methodology in an interview he once gave, saying that he had a triple compound compressing apparatus, and generated gas from sulphuric acid, iron filings and water. As the gas came out of the retort, he sent it through a tank of water, which would take the acid out of it. Another tank, with lime, would dry the gas.

“From that, it would go into this retort,” he said. “I had something like these big retorts, but I had just a small one. And then I would start my compressor, suck the gas out of that tank, and compress it into these cylinders that are pressured to 3,000 pounds to the square inch. Now it would give me about 200 cubic feet of gas into each tube. Those are the tubes that I took to the battle of Santiago and (used to fill) the war balloon.”

The Spanish American War broke out in 1898. Baldwin and his balloon were soon sent to New York to watch for the Spanish fleet and then to Tampa, Fla., for shipment to Cuba. After some difficulties with shipping of the balloon and a gas-producing wagon train, the balloon was ready to make its first ascent into combat on June 30, 1898.

As a tethered balloon used for observation, it was raised approximately 2,400 feet AGL, just over a ridge from Santiago Harbor, adjacent to the San Juan River, but well behind enemy lines. The mission was to watch for Admiral Cervera’s Spanish fleet to near the harbor.

Major Joseph Maxfield, chief of observation scouts, and Sergeant Ivy Baldwin, balloon pilot, made the first and third ascents that day. Once at altitude, Maxfield had clear line of sight of the soon infamous harbor. The Spanish Army also had clear sight of the gasbag.

The next day, the Spanish troops were about 650 yards from the observer’s position. Maxfield and Lt. Colonel George Derby, chief engineering officer for General William Rufus Shafter, U.S. Army commander in Cuba, went up in the balloon, and determined that the view was not optimal.

Derby ordered the balloon to be moved closer to the front. On the occasion of the balloon’s third and last flight, with Maxfield and Baldwin at the controls, now chillingly close to the action—the balloon became entangled in brush along the river, pulling it even more perilously closer to ground fire.

The Spanish, with their long range Mousers, began shooting at the prime target. Within minutes, the balloon was perforated with bullets and the whole menagerie came to rest in the San Juan River. The first aeronauts to be shot down, Baldwin and Maxfield both survived.

Baldwin fulfilled his enlistment in 1900, and then devoted full time to his daredevil activities.

In the summer of 1905, he demonstrated an airship he had made at Elitch Gardens. It combined a lighter-than-air bag with an engine driven propeller.

The balloon made many successful ascensions in Colorado, and many more at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, the Portland Exposition and in Los Angeles.

Baldwin, never quite satisfied with the performance of the “big yellow torpedo,” upgraded the airship’s gasoline engine. According to him, a salesman from out East talked him into using a “new fangled electric” one.

The airship met its demise on Oct. 6, 1906. As usual, Baldwin was at the controls when one of the batteries exploded, and the propeller was driven into the gasbag. The subsequent hydrogen explosion forced him to exit the craft at 30 feet AGL. Experienced at falling, he survived with minor burns and brushing.

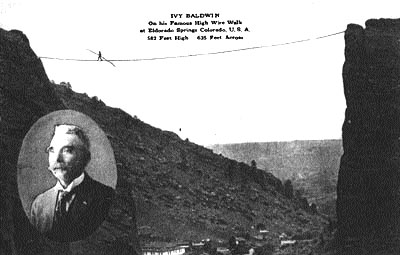

In 1907, he began a long association with the Eldorado Springs resort near Boulder, which was a family-oriented resort capitalizing on its healing waters. After bragging to some women about how he could walk across the canyon, Frank Fowler (brother of author Gene Fowler), one of three partners that owned the resort, and Baldwin strung a cable across the mouth of the canyon, stabilizing it with 32 ropes. It was 582 feet in height and 632 feet across. Baldwin’s first love had always been the tight-wire, which he began practicing early in life. On June 7, 1907, he made his first walk across the canyon.

He thrilled the crowds with his high-wire walks 88 times. On one occasion, he was blinded by the reflection of the sun off of the shear reflective rock, but completed the walk by listening to Fowler’s instructions, step by tenuous step. He also walked the cable backwards on several occasions. For his last trip across the canyon, Baldwin’s daughter and Fowler reluctantly strung a special wire, which was 125 feet high and 300 feet long, for his last walk on his 82nd birthday, July 31, 1948.

His highest walk was in Eldorado Springs; his longest walk was 820 feet at Hot Springs, S.D. He stopped high wire walking at this time in his life, as he put it, for the love of his daughter.

“If I don’t, she’ll sue Fowler for letting me do something so stupid and commit me to the sanitarium in Pueblo,” he said.

Airplanes

From 1909 to 1913, Baldwin worked with airplanes. His first airplane ride, in San Francisco, was in an airplane that he and two friends built, which was a copy of the Curtiss pusher-type plane.

His friends were carpenters, not daredevils, so to test the craft they turned the plane over to Baldwin to fly. He made a number of small flights in it, starting with a short flight of 100 feet, and gradually longer flights as he learned to fly the plane.

He would latter “crack this plane up” more than 19 times. After that, Baldwin flew a copy of a Wright design, fitted with pontoons for operations on Sloan’s Lake, at the time known as Manhattan Beach, in the metro Denver area.

Baldwin flew this hydroplane for the General Aviation Co., as the ultimate promotional gimmick in Denver and as the first seaplane operation in Colorado. His last flight was in 1913. The hydroplane flight was approximately 400 feet at only four feet above the water, and ended in a spectacular crash.

It was a wonder to all that he wasn’t killed, but to Baldwin, it was just another narrow escape. After a dispute with the manager of the company, Baldwin gave up flying for “safer pursuits,” and went back to tight-wire walking and ballooning.

Mistaken identity

Baldwin had many injuries and accidents, when balloons caught fire, or his airplane crashed. In September 1905, it was reported that he had been killed when a number of dynamite sticks he was using during a program demonstrating the battle of San Juan exploded, disintegrating his balloon.

However, it was a case of mistaken identity. Tom Baldwin was the actual victim. Another time, a drunk on horseback fouled a guy-rope for his high wire; the wire was literally yanked out from under him. The sudden stop at ground level resulted in several broken bones. Another time, a quick mountain storm caught him in the middle of his walk, and he was forced to hang by his knees for 45 minutes, until the storm passed.

There were some funny times, such as when he landed in a field of cactus while demonstrating in Mexico and another in Java, when he landed in a tree full of monkeys.

“They ran from me,” he said. “It was like a cyclone to hear the noise that they made going through the trees. They were little, not very big monks, you know. But they’re awful scary and they just screamed.”

Another incident was in Baltimore, where he was arrested for walking a tightrope. The authorities had classified that as an aerial act and the law required that he have a net beneath him. For the rather lawless west of 1883, in Denver, it was a common occurrence to see Baldwin, as the top billed attraction for the opening of a new business downtown, theatre debut, or the opening of a new saloon, walking between the rooftops, over Larimer Street—without a net!

Baldwin, not prepared, visited a nearby fishing village, bought an old net, and then put the net flat on the ground under his tightrope. The law had not specified that it had to be suspended, so he was lawful and continued his performance.

Ivy Baldwin lived many years in Eldorado Canyon, where he died, not in a balloon mishap, but in bed, at his home on Oct. 8, 1953, at the age of 87.

He was hailed many times in life and death, publicly and privately. Heads of state sought his company, for his unyielding courage, as well as his mastery of aeronautics and his down-home western wit.

In 1969, the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame honored Ivy Baldwin as inductee number one, stating that he displayed early in his life “a sincere urge to get into the air, one way or the other.” The induction was also due to the fact that he was the first person to fly a powered “air craft” in the state of Colorado, when he made a short flight in a self-designed and self-built powered dirigible-type balloon. He was honored by a number of groups, including the Early Birds of Aviation, since his first solo was prior to Dec. 17, 1916.

His final resting place is beside his wife in Fairmount Cemetery. A simple monument lists only their names and dates.

Information in this article is taken from a taped interview of Ivy Baldwin in September 1953, conducted by Fred Mazzulla, a prominent Denver lawyer and historian. Earl McCoy, a historian and member of the Denver Posse of Westerners International, wrote an extensive account of that interview for the Denver Posse of Westerners in March 1993. Other sources were microfilm of Baldwin’s scrapbook and the clipping file found in the Western History Department of the Denver Public Library. S.R. Alexander contributed to this article.