In the 1950s, the Denver Post photographed Dean Baird for a story in its now defunct Empire magazine about aerial crop dusting and spraying.

By Deb Smith and Cary Baird

Earl Dean Baird regards the world through eyes the color of a clear blue sky on a summer day. White, closely clipped hair and a strict sense of fairness have earned him the nickname “Grey Eagle.” He’s known as a pilot who flies by the book, not the seat of his pants.

“There’s not a better pilot around than Dean Baird,” says Dave “Doc” Callender, a flight instructor and Federal Aviation Administration designated examiner. “The same goes for his personal integrity. He’s one of the good ones.”

The 86-year-old aviator never met an airplane he didn’t want to fly—or an adventure he didn’t want to pursue. He came of age during World War II—a time when the early aviation pioneers had already made their mark and the aviation industry was beginning to shape America’s future.

His 1984 retirement from the FAA was just an opportunity for him to continue his adventures. In the past two decades plus, he’s given hundreds of flight checks, worked under contract to the Air Force Academy flight school, towed gliders and instructed scores of students. He’s gone scuba diving, taken a boat down the Nile, toured Israel, hiked through Petra, Jordan, sailed around the Bahamas and Florida, traveled through Baja three times, flown his Cessna 140 around the United States and followed the Louis and Clark trail by air.

Baird was born in Sterling, Colo., to Earl and Ella (Erickson) Baird, on June 24, 1920. In 1907, “Pop” and Ella Baird came to Colorado in a covered wagon, seeking the clean mountain air for Ella’s sister Carrie, who was suffering from tuberculosis. Carrie died near Sterling, and that’s where they stopped. They returned to Iowa for a short time before settling in Sterling permanently in 1912.

When Baird was born, his parents already had three girls and had lost three other children to the ravaging diseases of the early 20th century. Brother Keith’s arrival followed, almost exactly two years later. The boys would grow up as close as any two brothers.

During Baird’s youth, Sterling was a sleepy farming community. Wells and water from the South Platte River irrigated sugar beets and other crops grown on the Pawnee Grasslands. The railroad ran right through town, and the Union Pacific Denver Zephyr made a stop in Sterling between Denver and Chicago.

Small town life, hard-working parents, the Great Depression and Uncle Mauds (pronounced “moss”) Erickson shaped Baird’s values and work ethic. It also instilled in him a down-to-earth approach to life and people. A crusty Norwegian bachelor built like a moose, Uncle Mauds taught his nephews to build fences, drive mule teams, dig ditches and plant and harvest crops.

During that time, Pop Baird lost a business and a homestead, but his wife always managed to feed the family, even if it meant eating pancakes five days a week.

“I lost my taste for pancakes,” says Baird. “Today, I don’t eat them unless I have to.”

Dean Baird takes the back seat in this jet trainer with Dave “Doc” Callender, an orthodontist, flight instructor and designated FAA examiner.

One summer day in 1936, Ella Baird bought a ride in a Ford Tri-Motor for herself and her two sons, who shared a love of flying.

“I don’t know how she got the money, but this guy was giving airplane rides in a field west of town,” Baird said.

The brothers loved the experience. Two years later, Baird arranged an airplane ride for himself and a couple of his friends in a Cessna Airmaster—the taildragger that helped rescue Clyde Cessna and the Cessna Aircraft Company from oblivion in the 1930s.

“This plane hauled only four people,” explained Baird. “I was lucky enough to get stuck in the right front seat.”

As the slender young boy climbed in and shut the door, his eyes were opened to the world of flying.

“I thought, ‘Man, this is really something neat!'” said Baird. “All those instruments—and there weren’t really that many at the time—just beckoned me.”

Baird knew that aviation had to be a part of his life.

A career takes flight

At 20 years old, Baird learned to fly through the Civilian Pilot Training Program, a highly competitive government initiative started in 1939 to build up the number of U.S. pilots and boost general aviation. The government picked up the bill for each student’s 72-hour ground school course and 35 to 50 hours of flight instruction at select training facilities across the country. Both brothers were among those selected. Dean Baird soloed on Nov. 2, 1940, in Sterling.

“On average, only about 30 to 35 students showed up with any regularity,” he said. “If you did well enough, you got a scholarship to go on to further training.”

Again, the Baird brothers did well.

“My brother and I were lucky enough to be among the top 10 and were selected to go to Denver Park Hill Airport for training,” said Baird. “I finished up the CPTP in January 1942 with a commercial pilot instructor rating. I wound up getting a job at the same place I learned to fly in Sterling.”

Baird later worked at Pueblo Municipal Airport, where he met Vena Drain, an 18-year-old beauty who wanted to learn to fly. Their friendship and romance would last nearly 60 years.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S entered WWII. With its battles on two fronts, pilots and their skills were in demand. Anxious to contribute to the war effort, Baird approached his employer for a work release to join the Army Air Corps.

During World War II, both Dean (left) and Keith Baird served in the Army Air Corps. Both flew “The Hump” between India and China. Keith was killed in a plane crash in 1973 in Niles, Mich., where he was airport manager.

I figured I should be out there doing my part,” recalled Baird. “I got in the car, drove to California and joined the Army Air Corps as a civilian. I took my primary, basic and advanced training at Mather Field, near Sacramento.”

By that time, Baird was already an accomplished pilot.

“I came in under a special program for civilians; all you had to have was about 20 hours in primary, 20 hours in basic and 20 hours of advanced flying,” he said. “I already had more than a thousand hours on my own.”

From Mather Field, Baird was assigned to Carlsbad, N.M., where he would serve as copilot in a twin-engine Beech. In less than a month, he was transferred again, this time to the central instructor school at Randolph Field in San Antonio, Texas.

“It was a school to teach us how to instruct according to Army protocols,” explained Baird. “We spent half the day flying and the other half in ground school. It was a real opportunity to improve my flying techniques.”

Baird received his commission as second lieutenant and was sent back to California. He was first assigned as an instructor at Minter Field near Bakersfield. By that time, Drain had joined the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service organization and was assigned to a base near San Francisco. The two dated—often with several of Drain’s fellow WAVES in tow.

While in California, Baird requested an overseas assignment. After brief stops in Casablanca, Cairo and Arabia, he ended up in India, where he would join the war effort flying the Curtiss C-46 Commando from India to China. His brother was close on his heels. Both Dean and Keith Baird served in one of the most dangerous theaters of the war.

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had ordered the Army Air Force to open a supply line across the Himalayas to support Chinese General Chiang Kai-shek. The Japanese offensive was at its peak, and when Rangoon fell in early 1942, cutting off the Burma Road supply line, fuel was in critical shortage. Pilots like Dean Baird were brought in to transport planeloads of gasoline to allied forces on the ground.

They flew over the Santung mountain range in the Himalayas, nicknamed “The Hump.” Pilots put their lives at risk flying 55-gallon drums of gasoline over peaks as high as 20,000 feet. They faced not only inclement weather, but also hostile Japanese fire.

Conditions were poor at the airfields serving the China airlift; aircraft fuel was pumped by hand. But the type of flying was one of a kind, and Baird enjoyed landing on the China side.

“We could get fresh eggs, not powdered ones, for breakfast,” he recalled.

While in India, Baird sent $50 to Drain, asking her to buy books and send them to him. She kept the money.

“I knew then that I’d have to look her up again when I got back,” he laughed.

Coming home—to fly

In the summer of 2003, Dean Baird made two solo flights in his 1948 Cessna 140. The first trip followed Lewis and Clark’s trail; the second took him around the perimeter of the United States. Family and friends gave him a sendoff at Fremont County Airport

When the war ended, Baird boarded a troop ship and returned to the States. He wanted to remain in the military, but an orders mix-up resulted in his discharge.

“I went back to Sterling and bought a little flying operation there,” he said.

He continued to court Drain, driving to Pueblo nearly every weekend to see her. Finally, in late 1946, he told her they’d have to get married, because he wasn’t making the trip again. In January 1947, they eloped to Reno.

After Baird purchased the Sterling fixed base operation, he decided to start a Civil Aviation Administration approved flight school.

“So many veterans were interesting in flying, and they needed an approved school so they could use the GI Bill,” Baird said.

He owned the flight school for about a year, but discontinued it when he saw an opportunity to start an agricultural crop-dusting business, flying early sprayers such as the J-3 Cub, the Navy N3Ns and, eventually, the Stearman biplane. His new business partner was a Japanese mechanic from California.

“Hershel Abe had been interred, like many Japanese, during the war,” recalled Baird. “He was released from the camp, because the fellow I worked for in Sterling back in 1942 needed a good mechanic.”

Abe had started his own business and kept his shop at the airport in the back end of a T-hangar. Occasionally, a crop duster would land at the airport in need of gas or repair.

“One day we were watching the crop duster take off, and Hershel said, ‘We ought to be doing this for ourselves and not for someone else,'” recalled Baird. “That’s how we started.”

Baird & Abe Air-Ag Service soon became a strong competitor in the dusting and spraying business. The two entrepreneurs quickly became best friends, sharing stories, jokes and long, hard days on the job. They would do that for the next 11 years, eventually opening satellite operations in Greeley, Colo., and Wilcox, Ariz.

Baird’s personable disposition and cooperative approach with local farmers, as well as his acceptance for new technology, helped him build the business. It didn’t hurt that Abe was a mechanical whiz who could repair, modify or build just about anything. But after 11 years, Baird was burned out.

“I thought there must be a better way to make a living,” he said.

His work took him away from home for weeks at a time. By that time, he had two young daughters, Cary and Shirleen.

“I saw a notice about the FAA taking applications,” he said. “I told Hershel I was going to look at it.”

By 1959 he had been hired. That move would change his life and Abe’s.

“I had to get out of the business to avoid any conflict of interest, but Hershel said he didn’t want to do it without me,” Baird remembered. “So, we decided to sell.”

Government work turned out to be a good option for both men.

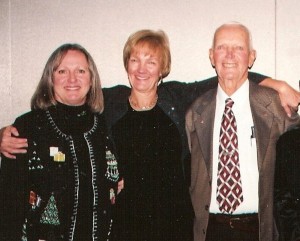

Dean Baird received a Master Pilot Award from the FAA in a ceremony in 2005. Shirleen Sabatino (left) and Cary Baird were on hand to celebrate the occasion with their father.

“Hershel went to work for the FAA as a maintenance inspector,” chuckled Baird. The two friends and their families remained close for the rest of their lives, often vacationing together.

Originally assigned to the Albuquerque office, Baird was able to transfer to Denver in 1962, where he remained for the next 22 years.

During his tenure with the FAA, Baird continued to enhance his already impressive resume. He obtained the airline transport rating, as well as ratings on a variety of land and seaplanes, single- and multi-engine airframes, rotorcraft and helicopters, gliders and even balloons.

His type ratings include the T-33 jet trainer, the Douglas DC-3 (C-47) and the NA 265 Sabreliner. For many years, Baird was the only check pilot in the Rocky Mountain area for those types of aircraft. By 1981, he had checked out in more than 80 different types of aircraft.

Baird joked that the only aircraft rating he’s missing “would have to be dirigibles.”

While serving with the FAA, his titles included supervisor of general aviation operations and unit chief of operations. Baird’s service there resulted in numerous commendations, including a special award for working with and mentoring minorities.

Looking back—and over the next horizon

In more than six decades of aviation, with 27 years at the FAA, Baird admits he’s seen plenty of changes, and not just in flying regulations.

“The biggest change I’ve seen in my time is the introduction of jet aircraft,” he said.

But Baird’s not afraid of change. When he says he’ll never quit being involved in aviation, no matter what changes come his way, you know he’s not kidding.

After retirement, Baird moved to nearby Canon City to be closer to the mountain cabin he loves. He continues to instruct students at Fremont County Airport, his home base in southern Colorado.

Baird experienced an extreme life change when his wife died unexpectedly in 1998, after nearly 52 years of marriage.

“She was one of a kind,” muses Baird. “She was a true partner, working alongside me in the spraying business and giving me the encouragement and freedom to pursue my interests. We had a lot of fun together.”

The death of a spouse sometimes starts a decline in the surviving partner, but Baird didn’t stop.

“My dad has such a positive outlook and a determination to experience things,” said Shirleen Sabatino. “Mom’s death was hard for everyone, but he did what she would have expected him to do—keep going!”

And go he did. Two momentous events were celebrated in 2003: the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition and the centennial of flight. Determined to honor these achievements in his own way, the 83-year-old Baird decided to make two commemorative trips—solo.

“I just thought I ought to be out there doing something for aviation,” he said of his treks.

First, he flew his 1948 Cessna 140 along the original route of the Lewis and Clark expedition, from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean. The trip took about two weeks. After returning home and making a few repairs on the 140, he began the second trip: a flight around the perimeter of the U.S. The little airplane made the journey in about five weeks.

True to form, Baird planned both trips with exacting detail, knowing how far he would go each day, the route he would take, what he wanted to see on the ground and how much gas he would burn. The 140 doesn’t hold much equipment; he took a small duffle bag, a tent and other survival gear, granola bars and water.

James Dean Baird holds the shirttail his grandfather cut from his shirt to commemorate his solo in Dean Baird’s Cessna 140 in the summer of 2006. The younger Baird, who took flying lessons from his grandfather, studied aviation at Metro State last year.

“My kids made me call home every night,” he laughs. “I told them they should have more faith in their old man.”

When he hit Kitty Hawk, home of the Wright brothers’ first flight, Cary Baird and his nieces, Bonnie and Maya, flew out to meet him and celebrate.

“I met some wonderful people along the way,” said Baird. “In Burlington, Vt., I even ran into a former Air Force Academy student I checked out in gliders years ago. He remembered me and pulled out his logbook to show me where I’d signed it.”

At 86 years young, Baird’s mulling over the possibility of flying the Lewis and Clark route again.

“If I do it again, I’ll take more time,” he said. “I missed a lot of the museums and sites along the way, and I’d really like to see them.”

All in all, Baird is content with the flight plan he’s been dealt. And he shows no signs of stopping. He plans to take a trip to Africa with Cary in the fall of 2007, including a safari in South Africa and a stopover in Casablanca, for old times’ sake. He’s inquiring about procedures to get an international pilot’s license, just in case he decides to do a little bush flying.

“I’m going to keep flying as long as I can,” he declares. “Even if I can’t fly any more, I’ll always be a part of aviation.”

Baird has served on the airport board for Fremont County for more than a decade. His contributions to Colorado aviation include significant advancements in aerial spraying and agricultural aviation, as well as helping cultivate the Air Force Academy’s glider program and improving its flight instruction.

His aviation achievements are impressive, but his accomplishments as a father, friend, partner and mentor are equally outstanding. Gwen Bosley, a longtime friend of Cary Baird, has called him “Paw” for years.

“He truly is one of my heroes,” she said. “I’m only one of a long line of those who admire and respect him and view him as a father figure.”

Another person who sees him as a father figure is Don G. Drummond. When Baird and Vena took off to Reno to be married, Vena wanted her cousin and good friend, Shirley Drummond, to share the momentous occasion, so Shirley and her husband Don accompanied them. The closeness between the two families led to a deep bond between Dean Baird and the son of Shirley and Don Drummond.

“Dean was like a father to me when I was growing up,” says Drummond. “He taught me nearly everything I know about being a man.”

Baird has been active in a number of organizations including the Hump Pilots, Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, Silver Wings, the Experimental Aircraft Association, Quiet Birdmen, the United Flying Octogenarians and the Colorado Aviation Historical Society. The Colorado Aviation Historical Society honored him with induction into its prestigious Hall of Fame in 1981. In 2005, he received the FAA’s Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award.