By Jeff Price

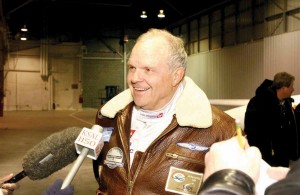

Tim Rogers, AAE, longtime airport director, has helped make Salina Municipal Airport a leader in airport industrial park development.

Some airports do some things well. Some are excellent at industrial park development. Some have capitalized on opportunity. Long and stable management characterizes some. And some, like Salina Municipal Airport (SLN), in Salina, Kansas, have done everything well.

Salina Municipal Airport has completely capitalized on industrial park development. In an industry like aviation–characterized by airline bankruptcies and very dependent upon the economy–industrial park development can guarantee airport revenue in good times and in bad. Industrial parks are also often good for the community by creating jobs and contributing to the economic health of the community.

The Salina Airport Industrial Center includes over 80 businesses, employs 4,700 people and has a payroll totaling over $4 million. One of the most prominent employers is the Schwan Food Company. What started out as a former Air Force building is now a 25,000-square-foot modern frozen food manufacturing plant. The construction of the building was funded by airport revenue bonds but Schwan has now grown to the point where it needs another building; the company will soon complete a 100,000-square-foot freezing facility.

“The industrial center activity is important to our overall success,” explains Tim Rogers, AAE, airport executive director. “Building and land rents generated from the industrial center provide us funds to use for the aviation side.”

Many of the industrial businesses take advantage of locating on an airport. Schwan operates Cessna Citation business jets that pick up and drop off their management personnel several times a day.

The industrial park concept is about to be taken to the next level–foreign trade zone status.

“It’s one of the projects we’re most excited about,” says Rogers. “We’re in partnership with Sedgwick County to include the airport industrial property and the airport through an interlocal agreement.”

Foreign trade zones have several benefits. When merchandise is imported into an FTZ and later re-exported from the zone, it’s never assessed any customs duties. Also, importers located in an FTZ are required to submit only one customs entry per week rather than on each item of merchandise, and duties on imported merchandise are deferred until the merchandise leaves the zone.

“A number of existing businesses at the airport industrial center will benefit from FTZs,” says Rogers. “Hopefully by the end of the year we’ll have that application finished and submitted.”

One factor contributing to Salina’s success is the resources it had with which to work. As the former home of Schilling Air Force Base, the airport came with several former U.S. Air Force facilities. The last 20 years have seen the conversion of those buildings into modern industrial facilities.

The base was also the home to the 802nd Air Division, operating B-52s, which left a nice long runway for the airport to use. The primary runway is 12,300 feet long. Three other runways are also available and shared by both commercial service and general aviation flights.

Management has also capitalized on numerous opportunities to improve the facility. One of the more prominent successes is Kansas State University’s aeronautical program.

Since 1991, when Kansas College of Technology merged with Kansas State University, the flight program has grown from a handful to over 300 enrolled professional flight students. The fleet includes 40 aircraft, from Cessna 150s to five brand new Cessna 172s with Garmin glass cockpits to a Cessna Citation CJ-1 that the university operates as a flying laboratory. By the time students are in their senior year, they’re earning right-seat jet time in the CJ-1.

The airport has also taken advantage of its location, roughly right in the center of the United States. It’s known as “America’s Fuel Stop,” with fuel sales totaling over four million gallons annually. Over 7,000 business jets a year land at Salina, on top of military training activity from T-38s, T-45s, F-16s and F-18s, which use the airport as either transit fuel stops or to conduct training missions at the nearby Smoky Hill Air National Guard range.

One area SLN has struggled with in recent years is commercial air service.

“The biggest disappointment is the scheduled air service trend over recent years,” Rogers said. “It’s a heck of a roller coaster ride for any small rural community. We’ve had some great peaks; we’re now in one of those valleys.”

Enplanements at the airport went from 10,000 to 13,000 passengers per year in the late 1990s down to 2,500 by 2004. The drop off hit in 2001 as air carriers struggled through the financial crisis brought on by the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The Mesa Air Group, with Air Midwest as a subsidiary, currently serves the airport. The airlines providing service to SLN receive essential air service funding from the government.

“We couldn’t ask for a better partner in those airlines,” says Rogers. “They’re very open to a variety of ideas and ways to improve passenger enplanements. They stress reliability and on-time flights and they try to work as best they can with US Airways in Kansas City.”

Competition for air service usually comes from a nearby airport. However, Rogers states that people in Kansas are used to driving long distances, and consequently don’t think twice about driving 90 minutes to Wichita to catch a flight.

“In the western part of the U.S. people still drive long distances for meetings and to make airline connections,” notes Rogers. “Behavior and habits are hard to alter. We have two great interstate highways that provide area residents access to Wichita, and I-70 has access to Kansas City International Airport.”

Rogers remains optimistic that the airlines will once again be able to regain a sustainable level of profitability. Unfortunately, soon Salina Municipal will no longer be considered a “primary” airport. A primary airport is one that enplanes 10,000 or more passengers per year. Airports with that designation receive entitlement funding from the FAA. With the drop in status, SLN will now have to compete for discretionary funds with other airports in the FAA’s central region.

While enplanements have dropped, the rest of the airfield is experiencing both growth and notoriety.

“We’ll be completing the Flower Aviation customer service center and opening that up later this year,” Rogers said. “It’s a nice, modern facility to service their customers; it replaced the existing facility, which has been in place since 1978.”

Work continues on the aviation side as the airport gains additional recognition as a location for aviation service businesses.

“We’re actively marketing the SLN Aviation Service Center,” Rogers said. “One of our existing tenants, Aerospace Systems and Technologies, Inc., is the U.S. developer and installer of the TKS system, which is quickly becoming the leader in aircraft ice protection.”

The airport is looking to attract additional business jet and maintenance services, in addition to more hangar space and construction. SLN has gained notoriety as well with the January launch of the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer. The GlobalFlyer, piloted by professional adventurer Steve Fossett, successfully completed the first solo, nonstop, unrefueled around-the-world flight, taking off and landing at Salina Municipal Airport. (A video about the event is available at www.salair.org.)

Fossett noted that Salina was an excellent choice for the record-setting event due to the airport’s long runway and the support of the Salina community, K-State and the airport. Sir Richard Branson, owner of Virgin Atlantic, will team up again with Fossett and the airport to attempt to set the ultimate flight distance record for powered flight, again in the GlobalFlyer. Their sights are now set on a 29,000-mile, nonstop, unrefueled flight.

“Working with Steve Fossett, Sir Richard Branson, Virgin Atlantic Airways and the skilled composite team has been invigorating and eye opening,” says Rogers. “It shows that when you think big, set high goals and put a good team together, you can achieve results you almost wouldn’t think possible.”

What Rogers has learned from working with Fossett, the world’s most daring adventurer, and Branson, the world’s most eclectic billionaire, seems to have been an aphorism for his own airport career.

Rogers is a hometown boy, born in Salina. He grew up in Hutchinson, Kansas, and then graduated from the University of Kansas. (Wildcat fans, don’t quit reading; his son goes to K-State).

Rogers then did a year of law school in Topeka, but realized what he really wanted was a career in airport management. He started his airport career at GA-oriented Jefferson County Airport, located north of Denver. He had scheduled interviews with Frontier, Continental and Western Airlines in Denver, but took a maintenance position offered by Dave Gordon, Jeffco’s airport manager at that time.

“After the interview, I went back to my apartment in Topeka, packed up and headed to Broomfield, Colorado,” Rogers said. “I arrived on a warm Denver evening, and woke up the next morning with 12 inches of snow on the ground. I reported to work early and Dave said, ‘Good to see you. There’s a snowplow; good luck. Remember, any taxiway lights you take out, you pay for.'”

Rogers said he owes his start and early training to Gordon and the airport authority board at Jeffco.

“It gave me the chance to learn firsthand about airport operations, maintenance and security issues,” he said.

Rogers then moved to Greeley, Colo., as the assistant manager for Greeley-Weld County Airport, and finally to Salina Municipal Airport in 1985. He was one of the original founders of the Colorado Airport Operators Association and previously served as the president of the Kansas Association of Airports.

“Any professional needs to volunteer his or her time and efforts,” said Rogers, whose attitude and professionalism has certainly been the guiding force in making Salina Municipal Airport successful in so many ways.