A brilliant inventor, scientist and aviator, Dr. Forrest Bird is probably best known for developing

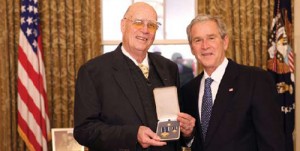

President George W. Bush stands with Forrest M. Bird of Sandpoint, Idaho, after presenting him with the 2008 Presidential Citizens Medal on Wednesday, Dec. 10, 1008, in the Oval Office of the White House.

the world’s first reliable, low-cost, mass-produced medical respirator. Through his innovation, Bird has helped transform and enhance the quality of life for people around the world, his invention

saving countless lives.

Bird was honored recently with the 2008 Presidential Citizens Medal (Dec. 10, 2008), standing in the Oval Office of the White House with President George W. Bush. This award commemorates Bird’s groundbreaking contributions and his tireless work to keep America at the forefront of discovery.

This prestigious award was established on Nov. 13, 1969, to recognize U.S. citizens who have performed exemplary deeds of service for the nation. It is one of the highest honors the President can confer upon a civilian, second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Since it was established by Executive Order in 1969, approximately 100 people have been awarded with this honor.

A doctor and aviator with numerous honors

In 2007, Bird received the Living Legends of Aviation Freedom of Flight Award, an honor shared with U.S. Senator George McGovern in 2008. The Freedom of Flight Award is given to the aviation community’s finest, those with pioneering spirits who have enhanced the industry and the world around them.

Bird, who resides in Sandpoint, Idaho, was also inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1995 for his unique fluid dynamics, which he employed in the invention of cardiopulmonary medical respirators. Bird introduced the world’s first mass-produced respirator in 1958. As the years passed, other Bird respirators were introduced, such as the BABYbird, which, inside a two-year period, reduced the death rate in low birth weight babies with respiratory problems (dropping from 70 percent to less than 10 percent).

During the 1990s, Bird introduced an advanced fourth generation of cardiopulmonary devices, this time employing a novel concept called Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation. This breakthrough has reduced deaths among severely burned patients with chemical inhalation injuries, from more than 60 percent to between 10 and 15 percent. Additionally, his state-of-the-art breathing machines continue to save thousands of critical care patients worldwide. The respirators not only save lives, but also improve the quality of life for thousands of home patients with advanced heart and lung disease.

It all began on a captured German plane

On a European B-17 delivery to Europe, Bird received orders to ferry a captured German Junkers Ju-88 from the British RAF back to the states for study. This trip would have a major impact on his future. An advanced demand oxygen breathing system was aboard the special high-altitude version of the Ju-88. U.S. aircraft were still using the A3A free-flow oxygen system with BLB facemasks. This restricted airmen to 28,000 feet, because of the inability of the free flow oxygen systems to maintain adequate arterial oxygen. It was a major limitation, since the P-38s, B-17s and B-24s had Minneapolis Honeywell Turbochargers, allowing the aircraft to fly above 30,000 feet.

During the flight across the North Atlantic from Prestwick, Scotland, with stops in Iceland, Greenland and Labrador before delivering the aircraft to Ohio, Bird became well acquainted with the German oxygen system. He discovered that releasing the oxygen during spontaneous breathing was hard work, due to the demand regulator. Determined to redesign the system, Bird removed the aft system and took it with him back to Long Beach. With the help of his flight surgeon, he devised an advanced pressure breathing system, employing revamped Mine Safety Appliance Gas Masks.

This was the first of many inventions that would transform the medical community and the lives of generations of patients.

Bird loves to fly

During the 1990s, Bird found a way to escape from his medical work. He built up a unique, noncommercial aircraft operation around an airfield on his ranch, which is surrounded by “some of the world’s most spectacular scenery.”

“When I look back on my life, I realize that without my aeronautical qualifications, I couldn’t have excelled in my various pursuits,” he said. “The time spent on aviation projects has always been my reward for succeeding in my medical projects.”

The pilot has about 20,000 combined flying hours, with about 5,000 military and 1,000 airline hours. Four hangars house his collection of aircraft and helicopters, which Bird says he used “like most people use automobiles.”

Bird says he dreads the inevitable day when he’ll have to stop flying. He also doesn’t seem too interested in ending his work with respirators.

“I’ve enjoyed doing all of this,” he said. “If you just did one thing all the time, it would be dull. I enjoy respirators; I enjoy flying. It’s a good life.”