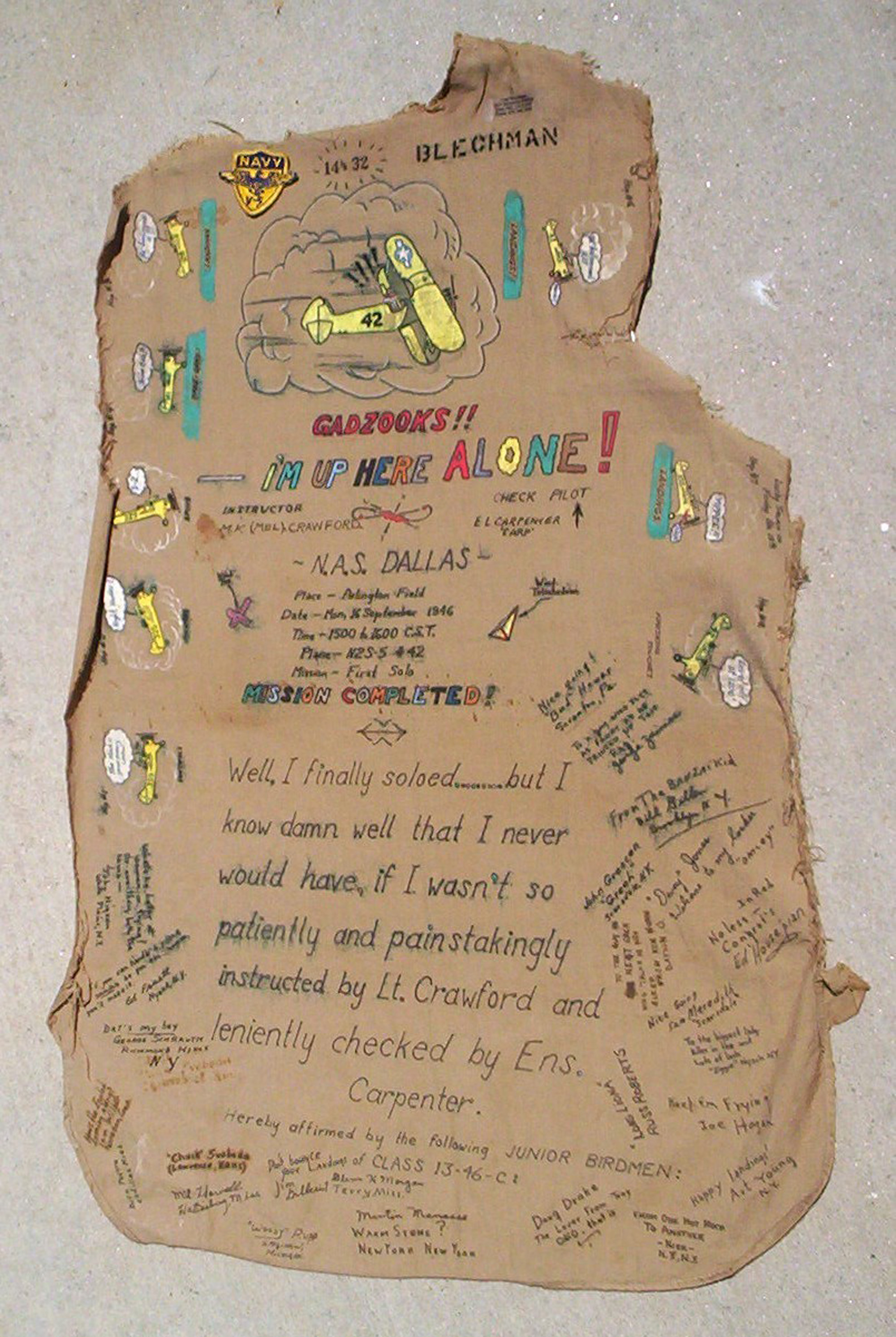

I decorated the khaki shirttail that was torn off my back after I soloed in a Stearman in 1946. Twenty-five other “mudholers” signed the bottom of the shirt.

By Fred “Crash” Blechman

It took 13 years, but my dream of becoming a Navy fighter pilot finally came true. I was nearly 10 years old on Sunday, July 4, 1937, when my parents took me to an air show at Floyd Bennett Field (a Naval Air Station at that time) in New York City. My face was pressed right up against a chain link fence when a small group of fat Navy silver and yellow fighter biplanes (I know now that they were Grumman F3Fs) flew over the field in a right echelon, peeled off, landed, taxied and parked no more than 50 feet from me!

I watched wide-eyed as the pilots, with their cloth helmets and goggles and flowing white scarves, climbed out of the tiny cockpits and clambered down the sides of their chunky fighter planes. I saw them gather together, tall and handsome, and was thrilled when they ambled over to the crowd at the fence. One of them even talked to me!

“Wow, I wanna be one of those guys,” I thought. “When I grow up, I’m gonna be a Navy fighter pilot!”

At that time it was just a dream. But I read flying books, built solid balsa-wood models and stick-and-paper flying models and devoured everything I could find about flying. Throughout World War II, I followed the exploits of the flyers, always planning that one day, when I was old enough, I’d join up to fly.

My chance came in January 1945, when I graduated from Far Rockaway High School in New York and applied for the Navy V-5 program. If I passed the physical and written tests, the Navy would send me to two years of contract college training before any pilot training.

I was 17 years old and not exactly a tall, handsome, muscular poster-pilot type. I was only 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighed only 135 pounds, with a slim 28-inch waist, was plagued with teenage acne—and didn’t even know how to drive a car!

Nevertheless, desire and determination overcame my shortcomings. I passed the physical, mental and psychological testing and got orders to report to Bethany College in West Virginia as an apprentice seaman for my first V-5 semester in early July 1945.

We were on active duty, always wearing our lowest-of-the-low apprentice seaman uniforms and marching to and from every activity. While I didn’t find the studies particularly hard, I found the physical activities difficult: constant marching drills and considerable physical training, including swimming, calisthenics and competitive sports. I wanted to fly, so I endured.

On August 6, about a month after I reported to Bethany College, the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. WWII quickly ended, and the Navy wondered what to do with those of us in the V-5 pilot pipeline who were still in the college training phase. By the time they figured it all out, I had completed the other three semesters at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and Columbia University in New York City.

It was now spring 1946, and the Navy was downsizing its need for pilots, preparing to close down the V-5 program. Instead of sending all who completed two years of college to 16 weeks of pre-flight training, a “weeding out” process dismissed those who were the least capable of learning to fly. “Selective Flight Training” took place in late 1946.

In August 1946, I entered the AvCad (Aviation Cadet) Program and was sent to Naval Air Station Dallas at Hensley Field in Grand Prairie. In class 13-46-C, my requirements were simple enough: solo after eight training flights and a check ride in a tandem dual-control N2S-5 Stearman “Yellow Peril,” or wash out!

Finally we were out of our seaman uniforms and into officer-like khakis with distinctive collar anchors and a neat embroidered V-5 cap insignia. We were really going to fly!

The eight Stearman flights were about an hour each, with instructors not particularly thrilled about their duty. The instructor sat in the front seat and spoke (yelled) to the student in the rear, through a rubber tube that extended from the instructor’s mouthpiece to the student’s special helmet. This was known as a “gosport.” The student could hear, but not speak! The instructor had a rearview mirror that allowed him to watch the student at all times.

It was in this intimidating environment that we went through the eight-hop syllabus: controls, climbs, spins, takeoffs, landings, landings, landings and finishing touches. As I recall, I had no particular problems with the flying, but I particularly enjoyed taxiing the plane around, since I didn’t drive a car!

I started flying on Sept. 3, 1946, and soloed on the 16th at Arlington Field, a Dallas outlying field where we practiced. My instructor was Lt. M.K. “Mel” Crawford, and my check pilot was Ensign E.L. “Carp” Carpenter.

I recall my first solo flight as one of the most thrilling times of my life, up to that time. The freedom and exhilaration of being in total control—just push the joystick to the side a bit and the whole world tilts!—and the great feeling of accomplishment on completing a worthwhile goal after, for me, considerable adversity. No one was telling me what to do through a one-way gosport or constantly watched me in a mirror. I was on my way to being a fighter pilot!

A common tradition is to cut off a pilot’s tie when he completes his first solo. But summer rainstorms are common in the Dallas area, and lots of muddy holes had surrounded the tarmac. So, in addition to clipping the tie, the first-solo initiation at NAS Hensley Field that summer was to tear off the AvCad’s khaki shirttail and throw the cadet in a slimy, worm-infested mud hole! When I stepped out of my plane at the main base, I got my initiation. I had “earned the mudhole,” and it took two long showers to remove the sticky mud and green worms. Yuk!

I survived that, and like many of the others, decorated the shirttail with colored cartoons and had the other guys sign it. I still have that shirttail. Some years ago, I located and talked with eight of those 25 “mudholers”—after almost 50 years!

We had been sent to Ottumwa, Iowa, in late 1946, in the cold, snowy dead of winter, for pre-flight and primary flight training. That’s when the Holloway Plan hit us. The war was over, and too many cadets were in the pilot pipeline. We were told we would have to sign up as aviation midshipmen for four more years—and couldn’t rise to ensign commission for two years, even if we earned our pilot wings sooner!

We were also told that if we stayed at Ottumwa through the cold winter, we’d be on tarmac duty, pushing Stearmans around for at least six months before getting into actual flight training. If we elected to return to civilian life and reduce the pool of flight trainees, we could keep all our neat officer-like uniforms, would receive $200 mustering out pay and were qualified for the G.I. Bill, to continue our education or take civilian flight training. What a deal! Considering my chances of completing flight training with the radical downsizing, I accepted the offer and left the Navy in November 1946.

I maintained contact with my former classmates and heard about the “Ab Initio” (From the Beginning) program they were beginning at Cabaniss Field in Corpus Christi, Texas—starting out in SNJs as the primary trainers instead of Stearmans. If I hadn’t left the Navy, I would have been in the first class!

This drove me nuts. I haunted the Navy recruiting office, trying to get back into Navy flight training. It took two years, but in November 1948, I got back into flight training and headed to Pensacola, Fla., for pre-flight. This time we were called NavCads (naval cadets), a designation that officially began on June 22, 1948, with the new Navy flight training program.

I completed pre-flight, then basic flight training in SNJs, with six arrested carrier landings on the USS Cabot (CVL-28) on March 23, 1950. I completed advanced flight training in F4U-4 Corsairs at Cabaniss Field and Corsair carrier qualification on the USS Wright (CVL-49) on Aug. 18, 1950.

On Aug. 23, 1950, 13 years after I saw the F3Fs at Floyd Bennett Field, I got my Navy wings of gold. I was naval aviator #T891. I was a Navy fighter pilot. My dream had come true.

In September 1950, I joined the VF-14 “Tophatters” at Cecil Field in Jacksonville, Fla., as junior ensign, flying the latest model F4U-5 Corsair. I made two Mediterranean cruises before separation as lieutenant, junior grade in November 1952.

After about 30 carrier landings in Corsairs, another dream came true: I finally learned to drive a car!

Fred “Crash” Blechman’s two flying books, “Bent Wings – F4U Corsair Action & Accidents: True Tales of Trial & Terror!” and “Flying With the Fred Baron,” are available at [http://www.amazon.com]. You can contact him at crash@airportjournals.com.