|

By Clayton Moore Ed Swearingen’s work doesn’t seem like magic to him. The remarkable transformations that this inspired aircraft designer applies to airplanes seem natural, even obvious. But to pilots and engineers with the know-how to appreciate his visionary designs, the innovations both large and small that Swearingen has imparted upon the aviation world can seem like alchemy. A mostly self-taught engineer who made a name for himself as Dee Howard’s renowned “miracle mechanic,” Swearingen learned the airplane development business at the side of aviation’s most famous entrepreneur, Bill Lear. After introducing groundbreaking modifications for existing production aircraft in the 1950s and 60s, Swearingen followed his own dream by launching a spirited campaign to produce new, revolutionary aircraft. The airplanes that Swearingen created during his marathon career include the Swearingen Merlin and Metro series, which became some of the most successful production airplanes of their time. In the 1980s, he demonstrated his entrepreneurial spirit by building a record-breaking kit plane, the SX300. The past two decades saw the development of the aircraft that represents the pinnacle of Swearingen’s career – at least, so far – the SJ30 personal business jet. Swearingen has been honored by his peers throughout his career, starting as far back as 1974 when he received the National Business Aircraft Association’s highest honor, the NBAA Meritorious Service to Aviation award. More recently, he was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame for his lifetime achievements in aviation, and was honored as a “Living Legend of Aviation,” joining an exclusive group of honorees that includes aviation entrepreneurs, innovators, record-breakers, astronauts, and flying celebrities. In a career-spanning interview with Airport Journals, Ed Swearingen reflected on nearly seventy years in the airplane business, from his humble beginnings helping America’s military in World War II, through his early career working elbow-to-elbow with some of the more recognizable names in the airplane business, and finally taking stock of his many successes in the field of aircraft design and production. |

Through it all, Swearingen’s formidable reputation in the industry has only grown with time. He has built an incredible body of work based on strong working relationships, the spirit of healthy competition, and a business philosophy that relies on setting impossibly high standards – and then shattering records with the results.

Taking Flight

In 2006, Ed Swearingen was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame for his numerous contributions to the aviation industry in his home state.

Edward J. Swearingen was born in 1925, on a farm in Lockhart, Texas. A farm is not only a great place to grow up, especially with parents like Ed’s that supported his early interest in aviation, but it’s also a fertile environment in which to learn to fix machinery. As a child, Swearingen was already building airplane models and by 13, he started to draft his own airplane designs.

Soon Ed, a self-admitted “eighth-grade dropout,” was ready to start getting his hands dirty in another tough environment. Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he began working as a civil service employee for the U.S. armed forces at Kelly Field (SKF), an enormous industrial complex near San Antonio devoted to supporting the U.S. Army’s Air Corps and the nearby Advanced Flying School.

“I spent my first five years of work in civil service,” Swearingen recalled. “I worked as an aircraft mechanic and also in the engine overhaul shop. At that time, Kelly Field was the biggest aircraft overhaul base that the Army had and we worked on B-17s, B-24s, A-20, A-26s, P-39s, and just about the entire family of U.S. armed service aircraft.”

He also helped to overhaul Galveston Army Air Field after the complex was devastated by a storm. Shortly after the war was over, Swearingen started taking flying lessons, mostly in Taylor and Piper J-3 Cubs.

“I have to confess that my earliest airplanes didn’t have any radios in them, so I used road maps,” Swearingen said. “Usually there’s a highway or a railroad going where you want to go anyway, but my navigation looking out the window wasn’t very good. I got lost a lot.”

Returning to San Antonio, Swearingen was intrigued by his father’s burgeoning education in electronics. His curiosity led to a posting to the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps at Fort Sam Houston as a senior electronics repairman, where he performed testing and overhaul of military and civilian radio receivers, transmitters and recording equipment.

“My dad said, ‘Well, since you’re not sure what you want to do, why don’t you come with me one night and see what you think about electronics?'” Swearingen remembers. “I did, and I just fell in love with it. It was a real shift in gears for me and I spent a couple of years learning electronics.”

His path soon crossed that of another Texas aviation pioneer, Dee Howard, who opened his airplane service shop, Howard Aero, in a shed at Stinson Field in 1947. In March of that year, Ed Swearingen became Howard’s first employee, and he threw himself into the work, ranging from aircraft engine overhaul to the installation of new autopilot systems.

A few years later, he fell into the orbit of another household name in aviation.

Learning With Lear

Famed pilot Clay Lacy, left, and Ed Swearingen’s history goes all the way back to their days at Piper, where Swearingen was a consultant and Lacy narrowly escaped a test flight in a Piper PA-Arapaho that crashed after a flat spin.

In 1949, Bill Lear was awarded the Collier Trophy by President Harry S. Truman for developing the Lear F-5 Autopilot, the first designed specifically for jets. Soon Lear was attempting to adapt the device for the emerging general aviation market.

A year later, Swearingen had a customer in San Antonio that happened to play golf regularly with Bill Lear in Santa Monica. Lear badly wanted to sell him an autopilot for his model 18 Beech, but didn’t have anybody in Texas to install it, leading to Swearingen’s first assignment.

“My customer told Bill Lear he had just the guy to install it,” Swearingen said. “The next thing I know, I have a whole bunch of boxes and parts and a wiring diagram for this autopilot, which I installed in this fellow’s airplane. But the instructions said, ‘Don’t turn it on. Bring it to California.’ Bill planned that he and I would turn it on together and fix whatever needed fixing.”

But the task wasn’t simple, so Swearingen got to demonstrate his instinctive troubleshooting abilities to Lear.

“It actually turned into a major redesign project because the device was essentially made out of rejected parts, and none of them worked the way they should,” Swearingen said. “After we got that patched up, we had to make changes so it knew how to fly a 180 mile per hour piston airplane instead of a 500 mile per hour jet.”

Impressed with Swearingen’s technical savvy and can-do attitude, Lear offered him a job. Swearingen took responsibility for numerous research and development programs on various navigation and autopilot systems.

There were a few bumps in the job, like one incident during which Swearingen had to rebuild Lear’s autopilot in the middle of a demonstration flight with a potential customer parked in the cockpit.

Ed Swearingen, inducted in the Living Legends of Aviation is seen here with other attendees at the awards gala in January 2007. L to R: Roslyn and Hank Beaird, Ed and Janice Swearingen, Kate Woolstenhulme, Roger Humiston and Tom Danaher.

“I was in the back of the airplane where the autopilot was located,” Swearingen said. “It wasn’t fastened down because I had it partially disassembled so we could make changes to it. Bill decided he was going to show this guy how well it recovered, and rolled about 15 or 20 degrees off-level and released the aileron, and about the time he did this big maneuver, that autopilot hit the floor and the gyros and vacuum tubes started flying all over the place. After I got it back together, I went to the cockpit and Bill was telling me that he had figured out that the problem was with the vertical gyro. I said, ‘Maybe that’s so, but I think it’s because the autopilot fell on the floor and the whole blamed thing fell apart.’ So we had a big laugh about that.”

Swearingen worked for Lear, Inc. as Assistant Director of Research and Development until 1954, and was an integral part of Lear’s development process in constructing his first corporate aircraft, the Learstar. Swearingen’s responsibilities including acquiring facilities, organizing the team of engineers and technicians responsible for design and construction, and managing various portions of the aircraft’s design. The whole time, Ed Swearingen was paying attention not only to Lear’s penchant for innovation but also to his approach to business.

“I was lucky enough to be in a position where I could lay back and watch what was going on,” Swearingen said. “Bill would go off on these trips, come back, and you’d find him explaining an idea to five guys around a drafting table. He’d be sketching something that he thought we ought to pursue and acting as if he was thinking it up as were discussing it. What I perceived over time was that while he was away, he had gone to find really talented people and learn from them. Then he would polish the idea up to the point where he knew exactly what had to be done. He wasn’t just dreaming it up as he spoke.”

Swearingen says he learned a lot from Bill Lear, including one lesson that would surface repeatedly when he was building his own aircraft.

“Bill always said that you have to ask yourself whether you’re the smartest guy in the room or not,” Swearingen remembered. “If you’re not, you go and get the guy who is. That doesn’t mean that he has to quit his job and come work for you, because it might be that half a day’s work on his part will give you what you need.”

One of Ed Swearingen’s early tutors in the airplane business was none other than Learjet founder Bill Lear, right, seen here with his son Bill Lear, Jr.

Even though their partnership only lasted a few years, Swearingen remembers his tenure at Lear fondly.

“Bill and I had a terrific working relationship,” he said. “I noticed early on that if someone offered a contradictory comment, Bill showed them no mercy. I made it a point to try to do what he asked me to do. If that didn’t work, I would try to do what I thought would fix it. Very often, I came up with a good, workable solution and Bill was always delighted that I hadn’t doubted him. I simply made an earnest effort to do what he thought should be done and if that didn’t work, I tried something else.”

Swearingen returned to San Antonio in 1954, where he rejoined Dee Howard’s company as Executive Vice President. His first duty was developing a new corporate aircraft, which became the Howard Super Ventura.

Essentially a comprehensive modification project, Swearingen and a team of engineers succeeded in redesigning Lockheed’s PV-1 Ventura, a World War II-era twin-engine patrol bomber, as a corporate aircraft. Powered by Pratt & Whitney twin R-2800 engines, the aircraft’s aerodynamic efficiency was increased dramatically by Swearingen’s modifications, increasing its cruise speed by more than 50 mph. The first delivery was made in May of 1956.

Swearingen also worked on the Howard 500, for which he designed and installed the pressurization components and built integral oil tanks into the wing. But by 1957, Swearingen decided to strike out on his own.

Even at that time, Lear was still so enamored with Swearingen’s talents that he asked him to come to Switzerland to work on the design for the Learjet.

“Bill offered to keep me on the payroll,” Swearingen said. “But in the end, I just couldn’t take him up on his wonderful offer. Instead I peeled off to go form my own airplane company in Texas.”

Swearingen Aviation Is Born

In 1958, Swearingen launched his new company, Swearingen Aviation. His objective was to hire himself out as an engineering consultant to other aircraft manufacturers and eventually manufacture his own proprietary products and aircraft.

One of his first clients was the Piper Aircraft Company. Piper was quickly joined by Bell Helicopter Company, Lycoming Motors, Pratt & Whitney and Garrett/Airesearch as Swearingen’s aviation company became the go-to shop for innovative aircraft modification and development.

One of Swearingen’s best-known projects for Piper was the development of the Piper PA-30 Twin Comanche, which evolved from the single-engine Piper PA-24 Comanche and became very successful for Piper. During the project, Swearingen became friends with Howard “Pug” Piper, the son of company namesake Bill Piper. The relationship also led to the development of Piper’s first pressurized airplane, the Piper PA-42 Cheyenne, and other development programs, most of which went very well. But every so often, a program went awry.

The prototype for Ed Swearingen’s innovative SJ30 personal business jet was donated to the Lone Star Flight Museum in Galveston, Texas.

“I can’t say enough nice things about Pug Piper,” Swearingen said. “Eventually, Piper wanted me to build a pressurized airplane like the Comanche, but with a single engine. I built them a pressurized prototype and it was a pretty good airplane that would reach 250 miles per hour.”

Unfortunately, Piper’s faith in one of his colleagues led the development program off course.

“Pug was so laid back about flying airplanes that he never really worried about other pilots,” Swearingen said. “He just thought everybody could fly them as well as he could. He taxied up in the prototype one day, got out of the pilot’s seat, and turned the plane over to a guy from Lycoming who was working on the engine. Unfortunately, he lost control on takeoff and ran into two parked airplanes, destroying it. That accident, plus the loss of control at Piper, kept it from going anywhere.”

Swearingen also modified several Piper Aircraft for famous pilot Max Conrad, who set numerous records for long-distance flight despite a nearly fatal 1929 accident with a propeller. In 1965, Swearingen made all the modifications to the airplane in which Conrad flew non-stop between Capetown, South Africa and St. Petersburg, Florida – despite the fact that Conrad accidentally forgot his maps.

“I remember saying, ‘Max, what did you do?'” Swearingen remembered. “He said, ‘Well, I remembered my first heading; I flew that until I came to South America and then I turned right.’ Working with him was a great pleasure. He was a heck of a nice guy, smart, and just a fun fellow with which to spend your time.”

Swearingen’s company also started performing research and development for Bell Helicopter, including the construction of many research helicopters. Swearingen’s work led directly to the development of a helicopter that set seventeen performance records as well as the Huey Cobra Gunship.

This picture was taken at Clay Lacy Aviation (VNY). Morgan Freeman arrived in the SJ30 just prior to the Living Legends of Aviation on Jan. 24, 2009. He does have one on order.

“We first built an open frame, primitive helicopter, similar to the Model 47,” Swearingen said. “By taking off the skids and adding wheels, we found that if it could make a running takeoff, it could carry enough fuel to fly the Atlantic with a few stops. It didn’t go anywhere but it was a really interesting experiment.”

The company’s expansion of the Huey Helicopter’s performance specifications was another breakthrough.

“We explored a combination of fixed and rotary wings,” Swearingen said. “We tilted the gear box forward so you could get some thrust out of the main rotor, and then we put jet engines on it. The most impressive thing it did was to fly 305 miles per hour on a small triangular course. I don’t know if that’s ever been beaten. It would hover and fly backwards and do everything that helicopters are supposed to do, but it would go like hell.”

While he’s best known for his aircraft designs, Swearingen has also been lauded for other technical achievements. In 1962, he was awarded the Federal Aviation Administration’s Aviation Safety Award for pioneering the use of exhaust gas temperature as an indication of fuel consumption in reciprocating engines. While working on a way to automatically feather the engines of Lockheed’s Loadstar, Swearingen discovered an interesting relationship between exhaust gas flame temperature and fuel air ratio.

“Truthfully, I’m kind of proud of that accomplishment,” he said. “I was the first guy to develop, certify and market a way to use exhaust gas temperature as a way to mix your own piston-powered airplane. Now practically every piston-powered single engine airplane in the world uses it.”

One of Swearingen Aviation’s best-known modification programs was the Excalibur 800, a conversion of the Beechcraft Twin Bonanza. While the most dramatic change was the addition of two new Lycoming IO-720 800-horsepower engines, Swearingen made several other improvements to the aircraft.

In one of the more interesting experiments of Ed Swearingen’s career, he equipped this Huey helicopter with fixed and rotary wings as well as jet engines, for a top speed of 305 mph.

“The Excalibur was an interesting mod, where we built new, more aerodynamic nacelles, new landing gear doors, and added a stair to allow entry without going over the wing,” Swearingen said. “Those turbo-charged engines made a big difference and quite a bit of the improved speed came from the increased altitude. We added a good 60 or 70 miles per hour to that airplane. We sold a bunch of them and then we built the Queen Air, which was a similar modification.”

One of the trademarks of Swearingen Aviation’s early aircraft was their memorable names, starting with the Excalibur. Swearingen remembers clearly how they originated.

“I called it Excalibur because the mythical sword was supposed to be a good cutting instrument and I knew this airplane would be a real cutter,” he said. “When we started the next one, I had a business partner who asked me, ‘Since you named that aircraft after King Arthur’s court, why don’t we call the next one Merlin?'”

Ultimately, Merlin became a fitting name for a plane that worked its magic on Swearingen’s customers, becoming one of the most popular corporate airplanes in modern history.

Conjuring The Merlin

In 1964, Ed Swearingen began putting together the first designs for what would become the Merlin and Metro series of multi-use aircraft. Asked if his primary goal was to compete with the Beechcraft King Air, the engineer laughed.

“No, I was trying to beat it,” he said. “And we did.”

Accomplishing another feat other said was impossible, Ed Swearingen recently re-equipped this military Boeing 707 with new Pratt & Whitney turbofan engines, raising the aircraft’s performance across the board.

The designer started off with a deceptively simple, ingenious idea: to build many airplanes out of one fuselage.

“When I set out to build airplanes, I had a good plan, but some things went wrong over time,” Swearingen said. “I set out to build a Merlin I, a Merlin II and a Merlin III. The Merlin I was going to be piston-powered and it was going to have a four-seat cabin. The Merlin II was going to be a turboprop plane with a longer fuselage and the wing was designed to fit on both planes. The Merlin III was going to be a jet airplane for which I would make whatever changes I needed to, mostly in the aerodynamic aspects of the design.”

Swearingen’s first hurdle came when he chose a custom-built Lycoming 540-cubic-inch engine to power the airplane. While Lycoming assured the company that the engines would be ready, delays on Lycoming’s part forced him to switch to Pratt & Whitney PT6A-20 turboprop engines, which necessitated the employment of modified Twin Bonanza wings and the implementation of a new fuel system.

The aircraft made its first flight in 1965, about fifteen months after the launch of the Beechcraft King Air, and was introduced to the market in 1966 as the Swearingen Merlin IIA. The plane became the principal competition for the King Air and the Merlin IIA and IIB products eventually acquired over 30 percent of the corporate market. By the time the last Metro 23 left the production line in 1998, a total of 1,053, Merlins and Metros were produced.

While Swearingen is pleased with the success of the aircraft line, he never quite realized his original vision for the design.

“I set out to build an airplane that I could make into a jet,” he said. “When I built the Merlin I, it was a terrific design and then the engines went wrong. I corrected that by going to a different engine but then I had to redesign the wing, and that’s not quite right. When I originally sat down to build that airplane, I said to myself that the world knows everything that it’s ever going to know about turboprop airplanes, so why not build one that is on the leading edge of the technology? When I started designing it, the idea was to make it as good as anybody knew how to do it. I still think that’s a logical idea, to roll up your sleeves and build a real airplane.”

The Merlin IIIA and IIB were produced until 1970. It was around the end of the decade that Swearingen became even more ambitious and pursued plans to build three new aircraft, which became the Merlin III, a significant redesign of the Merlin II; the Metro, a 19-seat pressurized airliner; and the Merlin IV, a 21-seat corporate version of the Metro with upgraded engines.

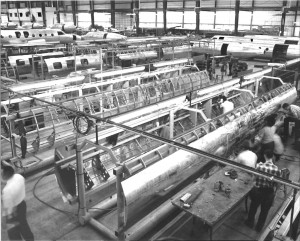

During the heyday of Swearingen Aviation, this final assembly line was kept busy cranking out Merlins and Metros, ultimately manufacturing more than 1,000 of the aircraft.

“I made the decision to build three new type certificates at the same time with a lot of commonality between the airplanes,” Swearingen said. “The reasoning was that everything I had done in my business had been easier to accomplish than I thought it would be. Everything that I thought would be unbelievably tough turned out to be easy except for one thing: the recession hit just at the point we assumed we could go to market. Just at the time when we had the best opportunity in the world, every airplane company in the world was in desperate trouble. It was a lot of bad luck that happened all at once.”

The economic recession of the early 1970s impacted sales dramatically, and the company only delivered 17 aircraft in 1971. In 1972, Swearingen sold 90 percent of the original company to Fairchild Industries. Swearingen continued to serve as Chairman of the Board for the subsidiary, Swearingen Aircraft Corporation, until 1982.

While adapting to his new role at Fairchild, Swearingen kept making interesting friends. A fellow scientist with whom he worked closely was Wernher von Braun, the rocket engineer responsible for the development of the V-2 rocket, the Saturn V launch vehicle, and many other aerospace programs. On July 1, 1972, the German aeronautics engineer became Fairchild’s Vice-President for Engineering and Development.

“When Wernher von Braun left Redstone Arsenal, he was told that he should get his head out of the clouds and work on more mundane things than space vehicles,” Swearingen said. “Fairchild teamed us together.”

Von Braun and Swearingen made regular visits to the Republic Aviation division of Fairchild Industries to track the progress of the emerging A-10 Warthog, which left both engineers suitably impressed.

“The interesting thing was that we supposedly had the best seat in the house,” Swearingen remembered. “I looked the situation over and I thought, ‘This isn’t so great. We’re so far away I don’t even know if we’ll know if it’s happening.’ Well, they lit that thing up and I decided I didn’t want to be any closer.”

Like many of the working relationships that he’s had over the years, Swearingen’s rapport with the legendary rocket scientist was always enlightening.

“Wernher Von Braun was just fun to work with,” he said. “He had a reputation as being a mean son-of-a-gun but we never had a cross word between us. I guess you could say we were both pretty uninhibited.”

Swearingen Fires Up His Jet

The 1970s became a time of transition as Swearingen began applying his design priorities of speed and range to jet aircraft more directly than ever before.

In 1973, he formed a new company, the Swearingen Aircraft Corporation, in order to start modifying aircraft again. His first contract partnered him with Lockheed and Garrett/Airesearch to update the Lockheed Jetstar.

“I had caused Garrett to build the TFE-731 engine and I had designed a transonic jet airplane to go with it,” Swearingen recalled. “We were just at the point of cutting metal when another recession came along and the program was cancelled. That’s how Lockheed became the first customer for the new engine.”

Swearingen began altering the Jetstar to use the new engines and modified its aerodynamic profile, promising the increased efficiency would also boost its range. Although Lockheed’s engineers expressed serious doubts about Swearingen’s modifications, his ideas proved sound.

“The long and the short of it was that Garrett did a transonic wind tunnel test model, which cost a lot of money,” Swearingen said. “The guys from Lockheed went up to see it. I didn’t go, because I was only interested in the numbers. I can’t see the wind blow anyway.”

The doubters were wrong by a long shot. Swearingen’s modifications increased the range of the Jetstar from 1,800 nautical miles to 2,800 nautical miles without increasing the fuel capacity, while simultaneously making it quieter.

Ed Swearingen, left, has met a lot of interesting people during the course of his career including award-winning actor, comedian and pilot Danny Kaye, at right.

In 1982, Swearingen retired from Fairchild to focus on his new company with the idea of re-entering the aircraft manufacturing business. He started with a progressive design for a small airplane.

“What caused me to make the decision to start building airplanes again was the fact that single-engine airplanes have been flying at the same speed since the 1930s,” Swearingen said. “I thought, since they’ve had the same speed all this time, why don’t I aspire to build an airplane with the same engines for the same cost as a Cessna that flies 100 miles per hour faster?”

Within two years, Swearingen created the SX-300, a two-place, low wing monoplane, which was offered as a kit from 1984 to 1989. Powered by a 300 horsepower, six-cylinder Lycoming engine, the SX300 raised the world speed record for aircraft in its class by 37 miles per hour.

“The reason I was building the kit was that I was going to get further down the learning curve where fabrication was concerned,” he said. “Once I had everything I needed for production, then I would certify it and stop building kits and start building fly-away airplanes. It was my bootstrap approach to becoming an aircraft manufacturer again.”

The plan didn’t come to fruition, partially due to Swearingen’s dissatisfaction with the kit market, but he kept inventing concepts for new airplanes. In 1986, he formed Swearingen Engineering & Technology, Inc. to market a new business jet, originally called the Swearingen Fanjet, which has evolved into the present-day SJ30. In designing the aircraft, Swearingen embraced his closely-held beliefs about the dichotomy between turboprops and jet aircraft.

“I’m just bowled over by the large number of turboprops being sold that are powered by jet engines,” Swearingen said. “If you look up and see an airplane fly over and it looks like a jet, there’s a good reason that it looks like a jet and not a turboprop. A straight wing is just laughable on a jet-powered airplane.”

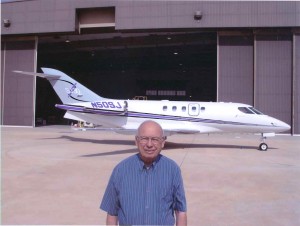

This recent photo finds Ed Swearingen showing off his most recent pride and joy, the SJ30 personal business jet that represents some of the engineer’s most innovative designs.

The SJ30, powered by Williams-Rolls FJ44-2A turbofans with 2,300 pounds of thrust each, is distinguished from many other small jets by its small, highly-swept wing designed for high-speed cruise. The aircraft has a maximum cruising speed of Mach 0.83, a range of 2,500 nautical miles, and a maximum altitude of 49,000 feet, making it among the fastest and most efficient light jets in the world.

“The size of the engine drives all of the costs, and that tells you how many people can afford to own the airplane,” Swearingen said. “If the airplane flies faster, the engine produces more horsepower. You get a great discount on the engine if you let the airplane fly as close to the speed of sound as possible. There are thousands of jet airplanes that are flying at least 150 miles per hour slower than they could if they would just change the geometry of the airplane. The people buying those airplanes are getting screwed because they’re buying a lot of engine that they didn’t need.”

The SJ30 has received a strong reception from the market, although the company experienced some setbacks during its development. The first proof of concept aircraft was shown at the Paris Air Show in 1991, and the first prototype flew in November of 1996. Regrettably, the second prototype crashed during a test flight in March, 2003, killing test pilot Carroll Beeler, a former Navy pilot and Vietnam P.O.W. The SJ30 received its type certificate in 2005, with its first delivery of serial number 006 to company investor Doug Jaffe in 2006.

Jaffe, a Texas tycoon with a long history in the aviation business, became a significant part of the company’s business history. In fact, the designation “SJ” stands for “Swearingen-Jaffe,” while the numeral 30 signifies the number of original designs created during Swearingen’s career at the time the plane was conceived. He later became a primary source of the capital needed to jump-start the production process.

The Piper Aircraft Company became one of Ed Swearingen’s best customers and he designed this single-engine turboprop prototype in the foreground for the company as well as the modified Piper Navajo in the background.

During his career, Swearingen never had trouble raising money. In fact, he jests, “Every time I decided I needed money, it walked in and surrendered.”

However, the affiliation between Jaffe and Swearingen has been based in friendship as much as economics.

“I’ve been blessed with good relationships,” Swearingen said. “I had breakfast with Doug on a Saturday morning and by Monday, I was using his money. We went a year without even putting anything on paper. I finally told him I’d write him a letter laying out what I thought the deal was between us, and if he agreed, he could sign it. I got it right back. Those are the kind of relationships you want to have.”

Other changes have affected the business in recent years. In 2005, Senator Jay Rockefeller of West Virginia, where the SJ30 is manufactured, brokered a major investment deal between the company and the Government of Taiwan. The resulting company was renamed Sino Swearingen. Unfortunately, the Taiwanese government’s influence seemed to hinder the company’s progress rather than enhancing it.

In 2008, new shareholders from Dubai came into the picture, restoring the aircraft’s production schedule. Emirates Investment & Development Company said in a statement that it plans to invest “about one billion dollars,” in the future of the company, now re-named Emivest Aerospace.

“I don’t think we could have found a better partner,” Swearingen said of the new investors. “They’re well-educated and a very respectable group of business people. I think for the first time that we have all the ingredients in place to achieve success.”

An Honorable Profession

Swearingen Aircraft Corporation’s re-engineering of this Lockheed Jetstar led to a range increase of 1,000 nautical miles as well as making it one of the quietest jets available.

When Swearingen trademarked the name “Edward J. Swearingen Aircraft Company” in 2007, analysts speculated that he might be launching a new enterprise, but he says it was merely a move to preserve the Swearingen name.

“It wasn’t the result of any plan,” he said. “I don’t forecast the use of the trademark, but I take great pride in the fact that my name means something to the business, and a great deal more pride in keeping that association at as high a level as possible. I would be unhappy if someone found a way to use my name in this area, so I was finding a way to protect it.”

Just because the design for the SJ-30 is complete, it doesn’t mean that Swearingen is taking a breather. He continues to work on research and development for Emivest as well as pursuing other projects that intrigue him.

“There’s still a lot of tinkering in my role,” Swearingen said. “My principal responsibility is in developing future products. I spent a lot of time looking at different possibilities as to what an aircraft might cost, how it might perform, and how big the market might be.”

Some men with his longevity in the business might be thinking about calling it a day, but the thought hasn’t crossed Ed Swearingen’s mind. Although he finds time to spend with his wife Janice and two grown children, his work continues to invigorate him.

“When I was 65, I had an excellent opportunity to retire,” he admitted. “I had a company that was running itself and generating good revenue. I gave some thought to it but I finally decided that it was more fun working than staying home.”

His competitive spirit hasn’t dimmed any over the years and he still finds time to analyze the other players in his market.

“I spend a fair amount of my time trying to convince myself what the competition is doing, even though most of the time I don’t know a damned thing about it,” Swearingen said. “But you study the people who produce the products in your field. If you look at somebody’s products and technology long enough, you can tell what they’re apt to do. I think it’s extremely rewarding and entertaining to compete with very competent people. Every once in a while, you get to show them something they might have overlooked.”

A good example of Swearingen’s enduring proficiency has been his recent replacement of the engines on a Boeing 707 tasked by the U.S. military as a Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (J Star) aircraft. Swearingen competed with several major aircraft manufacturers for the chance to equip the aging aircraft with new engines.

“The J Stars are the biggest secret we’ve got, I think,” Swearingen said. “It’s an amazing airplane, filled with computers and engineers that can put a missile into a piece of real estate eight foot square. Boeing and Pratt & Whitney went through our numbers and said, ‘This airplane will never do what you say it’s going to do.’ We beat our performance estimates across the board and landed the contract.”

In other words, the lessons Swearingen has learned over the years have continued to serve him well.

“My secret is to know people who are the best at what they do and get advice when I need it,” he said. “The other side of the coin is to set standards that are hard as hell to meet. When I decide to start something, I set standards and objectives that I know are questionable. But if I set the bar lower, I won’t do better. If I set goals that are almost out of sight, I may not make all of them, but the ones I do achieve will add up pretty good.”

Swearingen’s dedication to the superiority of his products is a virtue that sustains the quality of his work.

“I take it for granted that no one wants to buy an airplane from a start-up company,” he said. “That’s because airplanes aren’t thrown away after a couple of years like cars are. You may want to fly the same airplane for 10 or 15 years, so it can’t be done unless the people you buy it from are going to look after it. That means that if the design is deficient, they’re going to find an answer, as well as providing parts and manuals and everything else that a customer needs. The guy that’s buying an airplane is putting an awful lot of trust in the company that built it. So you work hard on these things to make them as practical as possible.”

Asked which aircraft he looks back on with the most satisfaction, Swearingen can’t formulate an answer, because he rarely considers the question.

“I’d rather talk about airplanes than anything else, but truthfully, I never give it a second thought,” Swearingen said. “Even before an aircraft is complete, I’m already thinking of what I might work on next.”

At the same time, the man with one of the best analytical minds in aviation does take pride in the work that he and many others have contributed to the aviation industry.

“I think it’s a very honorable profession,” Swearingen said. “If anybody delivers an airplane, two weeks later the entire world knows exactly how much fuel it uses and how fast it goes and every other fact about it. The airplane’s success is based on what it produces in terms of usefulness, how reliable it is, and how well it’s supported by the company that built it. There’s still an element of risk. But building an airplane is kind of like playing poker. If you’re really good at it, it’s a pretty predictable business. If you can do a good job at something, that’s about the best that you can hope for.”

Ed Swearingen has earned the right to stand proudly by his name, and his contributions to the field of aviation remain influential and enduring. The work, after all, has given his life a lot of meaning.

“I don’t have any regrets of any sort except for the time I’ve wasted,” he said. “Time is what it’s all about. If you build an airplane, it’s the time that people save by using it that makes it a good product in the first place. Your lifespan is definitely limited and the more you can accomplish, the more satisfying it is.”

One of Swearingen’s more challenging tasks was modifying the Piper aircraft flown by record-breaking long-distance pilot Max Conrad, which required substantial changes necessary for the pilot’s prolonged flights.