By Henry M. Holden

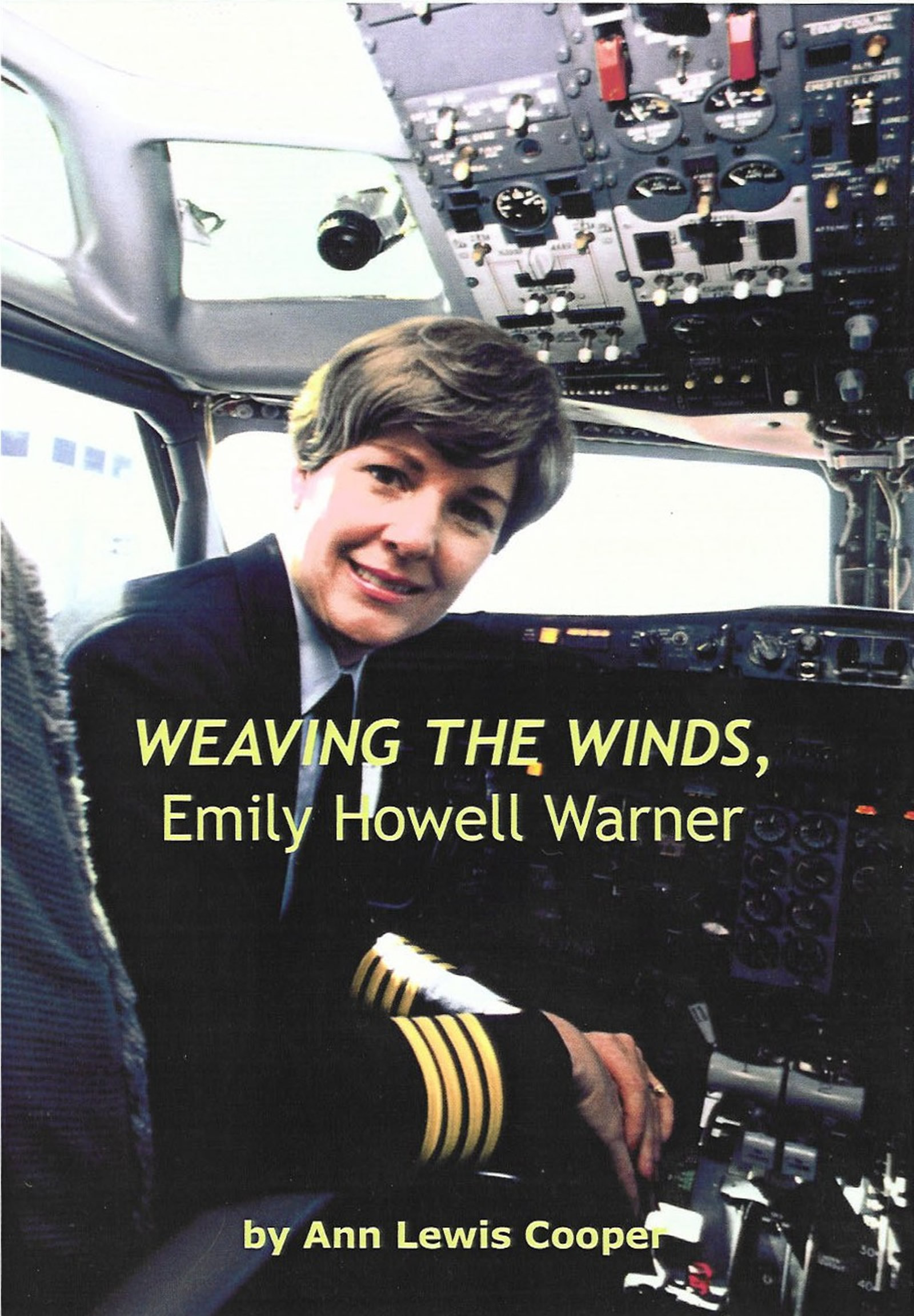

In “Weaving the Winds, Emily Howell Warner,” author Ann Lewis Cooper focuses on the first woman to fly for a U.S. scheduled jet-equipped airline (Frontier) as a pilot.

Ann Lewis Cooper is a prolific author of more than 700 magazine articles (not all aviation-related), and the author or coauthor of nine books. A certificated flight instructor who’s instrument rated, with more than 2,000 flight hours, she’s been working for years in the vineyards of aviation history, harvesting a rich and still under-represented field of notable and historic women aviators. In “Weaving the Winds: Emily Howell Warner,” published by 1st Books Library, she focuses on Emily Howell Warner, who, in 1973, became the first woman to fly for a U.S. scheduled jet-equipped airline (Frontier) as a pilot.

Aida DeAcosta soloed in a dirigible five months before the Wright Brothers conquered powered flight. Blanche Scott soloed a powered airplane in 1910, and in 1911, Harriet Quimby became the first American woman to earn her pilot’s license. For about 10 months in 1933, Helen Richey flew as a pilot for a scheduled airline (Pennsylvania Airlines, in Ford Tri-Motors) but the CAA insisted she only fly in good weather. Not wanting to be a “fair weather pilot,” she quit.

World War II brought more women into aviation as civilian flight instructors, and almost 1,100 into the Women Airforce Service Pilots, but the glut of male pilots after the war all but forced women out of commercial flying jobs. Emily Hanrahan, who took her first flight lesson on Feb. 6, 1958 (it cost $12.75/hr.) couldn’t have dreamed that exactly 15 years later, to the day, she would make her first flight as a pilot for Frontier Airlines.

But the years in between were filled with challenges, serendipity, opposition and change. Within two weeks of her first flight, she had her student pilot certificate. She knew how to taxi an airplane before she had her driver’s license, which she earned in August of the same year. She worked in a retail store for $158 a week to cover her one flight lesson a week, and later augmented her salary as a model.

|

By September 1961, she had 220 hours in her logbook, and was a certificated flight instructor. The sky had no limit—or did it? It was the turbulent 1960s; feminism, peace and love, and radical changes were taking place on the American landscape. But, not in this woman’s life, it seemed.

She married Stanley Howell in 1963. Within a few years they had a baby boy, Stanley’s namesake. As in many marriages, sometimes things just don’t work out, and the couple divorced. She faced another challenge, raising her son, and a fulltime career as a chief pilot and flight school manager. In 1966, irony and serendipity showed up on her flight path. United Airlines created an instrument training program in Denver, to train male pilots. The candidates needed a college degree and 160 hours of flight time. Ironically, UAL and other airlines had refused her interviews. They weren’t interested in hiring her as a pilot, even though she had hundreds of flight hours. |

While cultural changes were taking place in the 1960s, the thought of a woman airline pilot was just too radical then. She continued to rack up thousands of hours teaching potential male airline pilots instrument flying, and that would eventually lead her to walk into the Frontier Airlines office with more than 7,000 flight hours in her logbook.

The airlines never went looking for her; she went to them, again and again. She filed applications with several airlines in 1967, and updated them regularly. In late 1972, a male flight instructor who worked with her mentioned Frontier Airlines had hired him. She decided enough was enough.

“Back in the early 1970s, the airlines’ supply of pilots from the military service had started to taper off,” she said. “So flying jobs were opening up for pilots with other kinds of experience, and my 7,000 hours looked pretty good.”

“That’s not to say the airlines were eagerly looking for women pilots,” she continued. “I think they were looking for someone to break the ice, to see how the public would respond.”

The public responded with a deluge of letters. Her passengers applauded the airline and asked, “What took so long?”

The aviatrix had reached what for many pilots at the time was an unthinkable and impossible achievement, because she had the right mix of the “right stuff” and what would be later called cockpit resource management. She overcame the intrinsic resistance, and she understood the value of cockpit teamwork and cooperation. With a quiet, but firm focus on where she wanted to go with her life, Emily Howell Warner began to weave the winds of change, and of opportunity, to give wing to her own flying career. She became the first woman accepted into the all-male pilots union, the Air Line Pilots Association, and the first woman to fly as an airline captain. By setting an excellent example, she opened cockpit doors to the hundreds of women who followed.

She later flew for People Express, and then as a captain for Continental Airlines, and UPS, logging more than 21,000 professional flight hours. She left airline service in 1990 to work for the FAA, and retired in 2003. Her list of accomplishments is long, but perhaps two that she is most pleased with are her nomination into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2002, and her induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y. She is one of only eight aviators to be so honored.

“Weaving the Winds” ($23.95) is like Emily Howell Warner herself, uplifting and inspiring, and should be on the bookshelf of everyone interested in aviation. To order, call 937-426-0082.