By Bob Shane

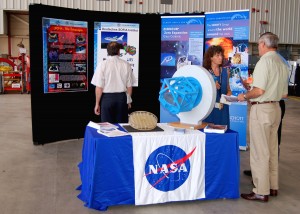

SOFIA, NASA’s highly modified Boeing 747SP, made its California debut at Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards AFB. The airborne observatory is the product of a partnership between NASA and Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft und Raumfahrt, German Aerospace.

Surviving budget issues, delays and possible cancellation, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy made its formal debut on June 27 at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, located on Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. SOFIA, a highly modified Boeing 747SP, arrived at Dryden on May 31 from Waco, Texas. It took an epic ten years to build the project, which was an international effort.

In Waco, L-3 Communications Integrated Systems converted the former airliner into the world’s largest airborne observatory. During a ceremony at the L-3 facility on May 21, Erik Lindbergh, the grandson of pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh, rechristened the unique aircraft Clipper Lindbergh. It was 80 years to the day since his famous grandfather completed the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight in Spirit of St. Louis, a Ryan NYP. Lindbergh christened the aircraft by splashing the contents of a vase across its name. The liquid was a concoction of champagne, recognizing Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight from New York to Paris; German beer, saluting the German consortium that built the infrared telescope; white wine, honoring Dryden Flight Research Center; and Dr. Pepper, honoring Waco, where the soft drink originated.

When Boeing delivered the aircraft to Pan American Airways back in 1977, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, wife of the famous flyer, christened it Clipper Lindbergh, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of her husband’s record-setting flight.

Erik Lindbergh shares his grandfather’s passion for flying. Lindbergh had long dreamed of tracing his roots by making his own transatlantic flight. Seventy-five years after his grandfather’s flight, on May 2, 2002, the younger Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic flying a Lancair Columbia 300, in 17 hours, 7 minutes. His aeronautical achievements are personal goals he’s set for himself.

“I walk in my grandfather’s footsteps without having to fill those shoes,” Lindbergh said at the christening. His Columbia 300 is currently at the Columbia factory and will soon be retired to the St. Louis Science Center.

Dignitaries and other guests heard Lindbergh talk about the aftermath of his grandfather’s accomplishments.

“Before my grandfather crossed the Atlantic, those that flew airplanes were considered barnstormers and fools,” Lindbergh said. “Afterwards, they became known as pilots and passengers. My grandfather was a thinker. His historic flight lit people’s imaginations, getting them to think outside the box. They soon began to see the potential of the airplane as a reliable form of transportation.”

Lindbergh says that today’s generation needs that spark.

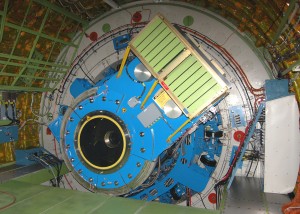

The German built telescope, the heart of the airborne observatory, is in the rear section of the Jumbo Jet’s fuselage.

“We’re in an age of considerable apathy,” he said. “Apathy is our top environmental problem. We need to light people up.”

SOFIA, in his estimation, has the potential to ignite a similar passion for scientific research and discovery, just as his grandfather’s milestone flight did in 1927. Following his speech, Lindbergh, aided by an audience countdown, rededicated the Clipper Lindbergh, pulling a cord that released a red, white and blue sash covering the name.

Speakers at the SOFIA unveiling ceremony also included Kevin Petersen, director of NASA Dryden; S. Pete Worden, director of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.; Rick Howard, deputy director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division; and Werner Klinkmann, deputy head of space science for Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft und Raumfahrt, the German Aerospace Center.

SOFIA will soon be taking off on its own pioneering mission. In the Lindbergh tradition, it will be pushing the envelope, adding to man’s knowledge of the universe. Its 2.5-meter infrared telescope will focus on profound scientific questions, such as the nature of creation and specifically how stars and planets are born. Its state-of-the-art optics will penetrate deep space, looking into black holes and probing the atmospheres surrounding planets in other solar systems.

“We will learn more about our system by looking at other systems,” declared Erik Becklin, SOFIA’s chief scientist and director of the airborne observatory.

Pan Am ordered the 747 Jumbo Jet in 1976 and accepted delivery the following year. Pan Am sold the aircraft to United Airlines in 1986. The aircraft flew its last revenue flight in 1994 and was withdrawn from service. NASA purchased it in 1997, and ferried it from storage in Las Vegas to San Francisco. Late in 1997, the FAA issued a new airworthiness certificate, classifying the aircraft as “experimental.”

NASA set up a program to convert the 747SP into an astronomy aircraft, awarding the project to a combined United States and German team. The modification work, converting the aircraft into a mobile telescope platform, commenced in May 1999, in a hangar in Waco. L-3 cut the first metal in 2000, when the installation began on a reinforced, pressurized bulkhead that helped create a compartment in the rear of the aircraft where the telescope assembly would subsequently be installed. Other modifications included installation of a 16-foot tall cavity door, which opens in flight to facilitate telescope observations. A complex liquid-nitrogen cooling system had to be installed to pre-cool the telescope compartment to match thermal conditions when the cavity door is opened at altitude.

The highly modified SOFIA aircraft made its first flight on April 26, 2007. During the two-hour test flight over Waco, it reached an altitude of 12,000 feet. The experimental SP was outfitted with instrumentation to record vibration data on the infrared telescope. On May 31, SOFIA was ferried from Waco to NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center on Edwards Air Force Base, California. There it will undergo installation and integration of mission systems and complete a three-year, multiphase flight test program before attaining total operational capability to conduct astronomy missions starting sometime in 2010.

NASA has a legacy of operating aircraft specially modified as flying observatories. In 1966, Dr. Gerard Kuiper, a renowned planetary scientist from the University of Arizona, used a 12-inch telescope pointed out the window of a Convair 990 in his research. It wasn’t long before an infrared telescope was mounted on a Learjet. Between 1974 and 1995, NASA operated a converted C-141 military jet transport known as the Kuiper Airborne Observatory. It carried a 36-inch reflecting infrared telescope. KAO’s scientific findings included the discovery of the rings of Uranus, a ring of dust around the center of the Milky Way, ultra-luminous infrared galaxies, complex organic molecules in space and water in comets. SOFIA’s infrared telescope will offer three times better image quality and higher sensitivity than KAO.

To obtain a complete picture of the universe, astronomers have to observe the cosmos in light from across the entire electromagnetic spectrum. In addition to visible light, objects in space emit energy-radio waves, infrared, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays that are invisible to the human eye. SOFIA will be able to see both the visible and the infrared. Because of the water vapor in the atmosphere, the infrared universe is invisible from the ground. The SP will carry its telescope into the stratosphere, operating above 40,000 feet, beyond 99 percent of the Earth’s water vapor.

NASA’s Ames Research Center will plan SOFIA’s science program; Universities Space Research Association of Columbia, Md., and the Deutsches SOFIA Institute of Stuttgart University in Germany will manage it. Its educational and public outreach programs will aim at increasing literacy in the fields of science, mathematics and technology.

- A plaque to be installed on the aircraft honors aerial explorer Charles Lindbergh and the rededication of Clipper Lindbergh to a new life of exploration as an airborne astronomical observatory.

- During the ceremony, Erik Lindbergh pulled a cord that lowered the red, white and blue sash covering the name of the aircraft and revealed the words “Clipper Lindbergh.”

- Kevin Petersen, NASA Dryden director, spoke about his expectation that SOFIA will join the ranks of the other great observatories, giving mankind a much different view of the universe.

- Peter Warden, director of NASA’s Ames Research Center, said SOFIA provided a real link between the “A” and the “S” in NASA.

- “We can now celebrate the debut of this great airplane,” said Peter Klinkmann, German Aerospace Center deputy head of space science.

- Erik Lindbergh, the grandson of Charles Lindbergh, rededicated the 747SP Clipper Lindbergh in honor of his grandfather.