FRONT ROW Aces Col. Art Fiedler, Col. Steve Pisanos & Col. Richard Candelaria STANDING visiting ace Lt. Cmdr. James “Schulz” Duffy, Col. Barrie Davis, Col. David Wilhelm, Maj. Fred Ohr, Lt. Col. Robert Goebel, & AFAA president, Cmdr. W. E. “Bill” Hardy.

By Larry W. Bledsoe

Six aces from the European and Mediterranean Theaters of Operation were guests of the Southern California Friends (SCF) on Oct. 5, 2008. These impressive pilots won most of their victories while flying the Mustang, but some also have combat experience in the cockpits of Spitfires and Thunderbolts. As they recalled their youth, their flight training and combat during World War II, a common thread emerged—each had realized his dream of becoming a fighter pilot.

The moderator, SCF President Dennis “Scott” Thomas, introduced other guests in the audience—Lt. Col. Robert Goebel, author of “Mustang Ace, Memoirs of a Fighter Pilot,” and Navy ace Lt. Cmdr. James Duffy. Another visiting fighter pilot, Lt. Col. Robert H. McCampbell from the 52nd Fighter Group, was there with his book “An Ordinary Guy in Extraordinary Times.”

After giving a brief biography of each ace, Thomas called on Col. Barrie Davis to speak. Davis joined the 325th Fighter Group in March 1944 and was assigned to the 317th Fighter Squadron, where he flew Thunderbolts. Davis said that WWII was a young man’s war. As an example, he pointed out that, like him, many of his fellow pilots were only 19 when they started pilot training. Davis’ performance earned him the rank Lt. Col. on his 24th birthday.

After enlisting, Davis and others were sent to the Santa Ana, Calif., classification center where they went through a battery of tests, both physical and mental. He jokingly said the smart guys were made navigators, the skinny guys became bombardiers and the rest were pilots.

Having flown both the Thunderbolt and Mustang in combat, Davis said the P-47s seemed like battleships with their eight .50 caliber machineguns. He said they could take a lot of punishment from ground fire when they were down on the deck and could still bring you home. His combat victories were all made in the Mustang, which he remembers as a great fighter, but he said an enemy round anywhere in the P-51’s coolant system would cause the engine to freeze up.

Col. Arthur Fiedler joined the 317th Fighter Squadron, 25th Fighter Group, 12th Air Force a couple months after Davis in May 1944. He racked up seven of his eight victories within five months. Perhaps his most noted victory was over a particular BF-109. Fiedler said that, contrary to stories otherwise, he did not shoot down that BF-109 with his .45 automatic. In fact, he didn’t even draw it.

Fielder remembers that day. They were on a fighter sweep and not tied to the bombers, cruising somewhere above 25,000 feet, when two BF-109s were spotted below. They went after them. During the pursuit, they were above and below the clouds, turning this way and that, climbing and diving until finally they were down on the deck.

Fielder’s guns had jammed (not uncommonly) during one of the high G maneuvers he pulled during the chase, and he found himself flying next to a German pilot. As they looked at each other, Fielder reached for his .45 out of frustration, but before he could draw it, the German pilot popped his canopy and bailed out. Why did the German pilot jump? Fielder says we’ll never know.

Also honored was Maj. Fred Ohr, the only American ace of Korean ancestry. He served with the 2nd Fighter Squadron, 52nd Fighter Group, until November 1944. He worked his way to the ranking of squadron colonel and flew 241 combat missions before returning stateside. His first victory was against a Ju-88 while flying a Spitfire. He then transitioned to the P-51 and shot down five more German fighters.

Col. David Wilhelm graduated from Yale in 1942 and earned his wings in March 1943. He joined the 31st Fighter Group in April 1944 and was assigned to the 309th Fighter Squadron. Between April 21 and July 3, 1944, he was credited with shooting down six German fighters. Wilhelm told his story in his book “Flyboys.”

Col. Richard Candelaria grew up listening to and reading stories about WWI aces, and knew he wanted to be a fighter pilot. After completing flight training, he was looking forward to a combat assignment but was instead sent to Luke Field, Ariz., to be an instructor. He was later trained stateside in P-38s before joining the 479th Fighter Group in September 1944, assigned to the 435th Fighter Squadron as pilot of a P-51.

(L to R) SCF President Dennis “Scott” Thomas, Col. David Wilhelm and SCF Vice President of Operations Michael Alonzo.

He said to become an ace you have to be at the right place, at the right time and do the right thing. He recalled an April 7, 1944, mission when he arrived at the rendezvous point over a bomber formation seven minutes before the rest of his squadron. Being a lone fighter, two German Me-262s came after him. While the 262s were making wide turns, he turned inside of them and kept them in his sights. Candelaria was credited with a “probable” that day, but he did not have time to confirm it because he was outrunning several BF-109s by the time it happened.

During the ensuing melee, Candelaria was diving on a BF-109 and saw orange balls floating past his canopy. He was surprised when he looked in his rearview mirror to see a BF-109 on his tail. Those orange balls were 30 mm rounds from the German’s nose cannon!

He broke off his attack and went back up to the bombers. His flight was still three minutes from the rendezvous point and he encountered a large formation of 109s and turned into them. There was no lack of enemy aircraft that day for him to attack and he was fortunate to have survived. Within the seven minutes he was waiting for the rest of his squadron to arrive at the rendezvous point, he managed to shoot down four Bf-109s in addition to the Me-262. Three weeks later he was shot down by anti-aircraft fire.

The last to speak was Col. Steve Pisanos who brought along his new book “Flying Greek.” Pisanos was born in Greece and when he was just 12 he knew he wanted to fly. It struck him after watching an aviator from a nearby military base perform aerobatics near his home. He later discovered that he didn’t have a chance of becoming a military pilot in Greece, so he joined the merchant marines at the age of 18 in hopes of reaching America and his dream.

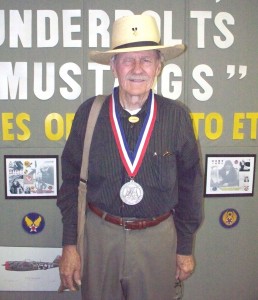

AFAA president, Cmdr. W. E. “Bill” Hardy, was recently inducted into the Commemorative Air Force’s American Combat Airman Hall of Fame. He is shown here wearing the medal he was awarded.

When his ship reached Baltimore, Steve jumped off with $12 to his name. He spent most of it on a ticket to New York City. When he arrived in New York, he had no money and no prospects. As luck would have it, he met two fellow countrymen who helped him find work in a Greek bakery.

He was eventually picked up by immigration officials, and after spending the night locked up, he talked to one of them. The official said that with the war raging in Europe he couldn’t send Pisanos back to Greece, so instead he classified him as a refugee and provided him with paperwork that allowed him to stay legally. Pisanos went back to work in the bakery.

When the opportunity came, he went to England and joined the Royal Air Force. He was later assigned to the 71 Eagle Squadrons flying Spitfires, even though he wasn’t an American,. When the Eagle Squadrons transferred to the 4th Fighter Group, 8th Air Force, Pisanos went with them. In 1943 he returned from a mission and was told to report to the American ambassador in London. There, he and some others were naturalized, and he officially became a United States citizen.

Pisanos shared several of his combat experiences about flying the Thunderbolt and the Mustang. He was on the first escort mission to Berlin, and on March 5, 1944, he was credited with two BF-109s before his plane went down near Bordeaux, France. He then spent six months with the French underground. Pisanos’ love for the nation for which he fought was evident as he closed by pointing to the American Flag and said, “I’m very proud to be an American!”

Larry W. Bledsoe is an avid aviation historian and writer. He can be contacted at (909) 986-1103 or at lwbcpf@aol.com or www.bledsoesbooksandart.com.