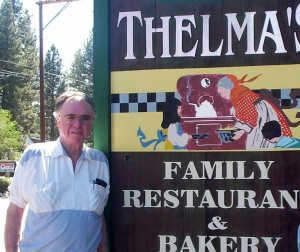

Doug Rankin (left), retired United Airline pilot with 27,000 hours, has been flying his 1956 Cessna 182 since 1974. Neil Houston, retired after more than 38 years as a mechanic for American Airlines, likes to go on light plane rides.

By Fred “Crash” Blechman

Some plans take longer than others to materialize. Such was the case when Doug Rankin, retired airline pilot, suggested we fly up to Big Bear Lake for lunch in his Cessna 182.

“Sure,” I replied. “When can we go?”

“The annual on the airplane is coming up, and the weather is a consideration this time of the year. I’ll let you know,” Doug replied.

That was last fall. Winter came. Then spring. Then, what we here in Southern California usually call “June gloom” arrived early. This daily morning heavy overcast, which would sometimes last all day, began in May this year.

Finally, in late May, with the annual inspection of the aircraft completed and the weather improved—but still not ceiling and visibility unlimited—three of us made it to Doug’s hangar at Pacoima’s Whiteman Air Park in the northeast corner of the San Fernando Valley.

Along for the ride was Neil Houston. Neil had spent four years in the Navy as an AE2 (aviation electrician petty officer second class) in the early 1950s, then spent more than 38 years working as a mechanic for American Airlines, doing whatever was required, from electronics to engines. Although not a pilot, Neil likes to go for airplane rides.

We pulled the plane out of the hangar. This is an original 1956 model, the first year the Cessna 182 was offered. Doug’s had various other planes and has owned this one since 1974. Powered by a six-cylinder, 230-hp Continental O-470 engine, N5782B has a straight 180-type tail, rather than the swept tail in 1960 and later models. Doug has the original instrument panel layout and displays this plane at various airports as an antique. It still uses the old, small, rectangular type of gyrocompass that he flew in his first DC-3 flights.

Yes, Doug Rankin goes back to the days when the Douglas DC-3 was the most popular airliner. He learned to fly in an open-cockpit biplane when he was 16, earned his private pilot license at 17, then his commercial and flight instructor ratings and was teaching flying when he was 18. By 19, he had his instrument and multi-engine land and sea ratings. He taught flying while he was going to college, and on summer vacation in 1952, he worked for Hawaiian Airlines and went to Honolulu to fly as a copilot on DC-3s.

After college, Capitol Airlines hired Doug to fly the DC-3, Lockheed Constellation, DC-4 and the Vickers Viscount, until Capitol Airlines merged with United Airlines in 1961. Then he flew DC-6s, DC-7s, Constellations, DC-8s, DC-10s, Convair 340s and Boeing 727s, 737s and 747s. He finally retired in 1990, after flying as a 747 captain on Pacific Ocean routes to Australia, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore and Tokyo. His total flying hours exceed 27,000, with about 1,200 hours in his 182. I concluded that it’s safe to fly with Doug Rankin, who is courageous enough to fly with a copilot whose call sign is “Crash!”

Doug Rankin likes to fly up to Big Bear Lake for lunch at Thelma’s Family Restaurant, two blocks from the airport.

It was time to go flying. The initial overcast had burned away over Whiteman Air Park, but broken clouds remained above Los Angeles, the most direct way to Big Bear Lake. Doug decided we’d fly out the Newhall Pass and turn right to the Antelope Valley, flying just north of the San Gabriel Mountains to approach Big Bear from the northwest.

Neil climbed into one of the two rear seats, Doug got in the left front seat, and I occupied the right front seat. We buckled up, and Doug started the engine and received tower clearance to taxi. Using nose wheel steering with the rudder pedals and toe brakes, Doug guided the plane to the run-up area, where he tested the prop, carburetor heat and magnetos. Cleared for takeoff from Runway 21, we were airborne in about six seconds at 12:30 p.m., with 2,500 rpm and 26 inches of manifold pressure.

The air was bumpy as Doug made a left-hand departure, over the Hansen Dam Recreational Area, resetting the power to climb at 500 feet per minute and 90 mph. He turned to 320 degrees to clear the mountains on our right. Following the Golden State Freeway toward Newhall and Santa Clarita, I took the controls, turning northwest and following the Antelope Valley Freeway toward Palmdale. We kept climbing as we turned east and then southeast, keeping the San Gabriel Mountains to our right, finally leveling off at 9,500 feet. We cruised along at 120 mph, with poor visibility ahead, but good visibility to the north.

Here’s where I have to comment on my flying. Back in the early 1950s, I flew planes with gyrocompasses—the little rectangular kind like Doug has in his airplane—and could always figure out which way to turn to a desired heading. But in the intervening years, I’ve been spoiled by gyrocompasses that have a full 360-degree display and an airplane figure that you simply point at the heading you want. It’s real easy to decide which way to turn. But the old rectangular type showed a center line only and 25 degrees on each side. When Doug gave me a new heading—using a small GPS unit mounted on his yoke—half the time I turned the wrong way! He had a neat purple line on his GPS for the airplane symbol, but I couldn’t see his GPS from my position. I bow my head in shame!

As we approached the San Bernardino Mountains on our right, we changed to an easterly heading, and ahead on our right was Silverwood Lake. We began a descent as we approached Lake Arrowhead and could see the much larger Big Bear Lake directly ahead. Doug took over the controls, flew just north of Big Bear City, made a 180-degree turn to the west, flying south of Big Bear City Airport, all the while descending into the 8,000 foot traffic pattern for a right hand approach. We watched for other aircraft, since the airport has no control tower. Doug made a smooth landing on Runway 8 at 1:30, ending the one-hour flight.

We tied down the aircraft and headed out for lunch. Although the field has two restaurants, Barnstorm Café and Mandarin, Doug, who had been there several times in the past, recommended Thelma’s Family Restaurant & Bakery on Big Bear Boulevard, about two blocks east of the airport terminal building. We had a leisurely, pleasant and inexpensive lunch on Thelma’s patio, where they have an all-day breakfast special for $4.95, as well as a multi-page menu.

We walked back to the airport. By that time, it had warmed up, and we wondered what the density altitude—which effects airplane and engine performance—had become as a function of temperature and atmospheric pressure. Although the runway elevation is 6,752 feet, as we approached the takeoff point of Runway 26, a sign indicated the density altitude was 9,000 feet—thin air. This meant a longer takeoff run due to reduced engine power and more airspeed required for lift and climb. No problem. With the 5,850-foot runway, Doug got us off OK—but it did take about 12 seconds, instead of six, to get airborne at 3:30.

We had a lot of haze, but the clouds over Los Angeles had cleared. I flew the plane after takeoff, over San Bernardino and then west over the many cities just south of the San Gabriel Mountains. The visibility, into the lowering sun, was poor, but good to our left. Soon, we were approaching Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, and Doug took the controls and landed at Whiteman at 4:15—a 45-minute flight. A pleasant afternoon—and the first time I’ve been to Big Bear Lake since we took our children up there 45 years ago for several days every summer! Where has the time gone.

Fred “Crash” Blechman’s two flying books, “Bent Wings – F4U Corsair Action & Accidents: True Tales of Trial & Terror!” and “Flying with the Fred Baron,” are available at [http://www.amazon.com]. Contact him at crash@airportjournals.com.