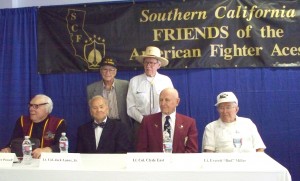

Seated L to R: Col. Lawrence Powell Jr., Lt. Col. Jack Lenox, Lt. Col. Clyde East and Lt. Everett “Bud” Miller. Standing: Lt. Cmdr. James “Schulz” Duffy and Cmdr. W. E. “Bill” Hardy, AFAA president.

By Larry W. Bledsoe

The Southern California Friends of the American Fighter Aces Association held its first symposium for 2008 at the Vought Aircraft facility in Hawthorne, Calif. on June 8. SCF president Dennis “Scott” Thomas was the moderator for the event, which featured four speakers: Lt. Col. Clyde East, Lt. Everett “Bud” Miller, Lt. Col. Jack Lenox and Col. Lawrence Powell Jr.

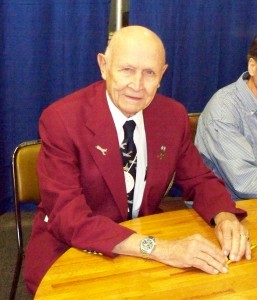

Lt. Col. Clyde East

Lt. Col. Clyde East was credited with 13 victories during World War II while flying an F-6D, the photoreconnaissance version of the P-51 Mustang. His numerous victories disproved the perception that photoreconnaissance pilots rarely encountered enemy aircraft on their missions.

East’s photoreconnaissance work during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 was at the center of the confrontation. Fidel Castro was working with the Soviet Union to build missile sites in Cuba. The sites would have nuclear-armed missiles with enough range to target Washington, D.C., and most of the eastern half of the United States. High-altitude U-2 intelligence photos showed military sites under construction that could be missile sites, but the details from those photos didn’t provide sufficient information to verify the type of sites.

East was one of the pilots from his photoreconnaissance squadron given the assignment to photograph the sites from altitudes ranging between 500 and 1,500 feet. Flying RF-101 Voodoo fighters, he and his wingman photographed two of the six identified sites. The photos verified they were for long-range missiles that could reach deep into the U.S. The photos also revealed that the sites would be operational within days.

With Soviet ships were on their way to Cuba with missiles for those sites, President Kennedy took immediate action. On Oct. 22, 1962, Kennedy came on the air stating that the U.S. had serious trouble with the Soviet Union about missiles. What he didn’t say was that the U.S. Air Force and Navy were in position, waiting for his orders to take out those sites as well as prevent the missiles from reaching Cuba.

For several days, those in the know, including East, held their breath waiting for a response from the Soviets. Finally, Kennedy announced the Russian ships had turned back and the crisis was over. It was the closest we came to warfare during the Cold War.

Lt. Everett “Bud” Miller

After graduating in class 43K, Lt. Everett “Bud” Miller went to Santa Maria, Calif., for fighter training. Upon graduation, he and his classmates were deployed overseas. When they reached New York City, they learned they were headed to North Africa as replacements for P-38 squadrons.

Miller’s first combat mission was the day after he arrived at the 94th Fighter Squadron. His commanding officer assigned Miller as his wingman for the mission, barking, “Get on my wing and stay there!”

Halfway to the target, enemy aircraft were spotted heading in their direction. It was a German tactic to head for the American P-38s as if to attack. As soon as the Americans dropped their tanks, the Germans would pull away, knowing that the Americans didn’t have sufficient fuel to continue their escort mission to the target. Knowing this, the CO waited until the last moment before taking action.

Lt. Col. East, with 13 victories, got his victory on D-Day—an FW-190—over Laval, France, while on a photo mission over the Normandy beaches.

Miller dropped his tanks when the CO did, and followed him in a right turn towards the enemy aircraft—then both his engines quit. He quickly switched to the main tanks and the engines burst back into life, but in the meantime, he had lost his squadron leader. Back at the base, when Miller told his CO about forgetting to switch fuel tanks before dropping his auxiliary tanks, the CO told him he had done the same thing on his first mission.

Miller said they flew 12 or 13 missions to Ploesti oil fields in Romania, which was a 650-mile trip. Ploesti was an important target—it was a major source of fuel for the Germans. The pilots tried many times to knock it out. Those missions were particularly unforgettable because it was such a tough target. They usually flew to Ploesti on the deck.

“So low they were cutting grass,” was the way Miller put it.

They tried hitting the targets using different tactics—approaching the target from on the deck, from different altitudes, and they even tried dive-bombing. That didn’t work because the Lightnings built up speed so fast in a dive. Miller said that on one mission, a much larger flight of enemy fighters jumped his squadron, and at other times, the flak was so thick you could walk on it.

Lt. Col. Jack Lenox

Lt. Col. Jack Lenox flew P-38s with the 14th Fighter Group. He’s one of 2,500 pilots that graduated as staff sergeants early in the war, when most pilots received their gold bars upon graduation from flight school. Before his deployment overseas, Lenox received a promotion to flight officer (equivalent to a warrant officer today). He and his classmates trained to fly P-51s, but when they arrived in North Africa, his assignment was flying P-38s; he went into combat with no gunnery practice.

On his first mission, his flight encountered German aircraft that were attacking the bomber formation they were escorting. During the encounter, he dived in his P-38 at 550 mph, pulled out behind four Me-109s and started shooting. To his dismay, he was going so fast that he flew right on through the enemy formation, and then they were on his tail. He climbed out so fast that he grayed out. When his vision cleared, no enemy aircraft were in sight and he couldn’t find the group CO, on whose wing he was supposed to be flying. Then he spotted another lone P-38 heading in the correct direction and decided to join up with him. It turned out to be his group CO, who thought Lenox had been with him all the time. Lenox received his commission as a second lieutenant in April 1944.

Col. Lawrence Powell Jr.

Col. Lawrence Powell Jr. flew Mustangs with the 339th Fighter Group. According to records, he was shot down on Jan. 14, 1945, on his 68th mission. He prefers to say he flew 67 3/4 missions.

“Well, it’s easier to say I was shot down than to explain what really happened,” said Powell, while describing his experience.

He liked to shoot up locomotives, and on this particular mission, he was going after another one when his left wing cut some high-tension wires. The wires did a great deal of damage to his wing, tore out one gun and ripped the others out of their mounts, causing them to stick up at odd angles.

R to L: Larry Bledsoe visits with AFAA historian Frank Olynyk, author of “Stars and Bars—A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920 – 1973,” and Trevor Constable, co-author of “Fighter Aces of the U.S.A.”

He climbed to 11,000 feet, where his flight encountered a large formation of German fighters. He took his flight off to the left, but his coolant popped and he needed to bail out. The canopy wouldn’t come off, and he knew he had to land before the engine froze up. He was able to get short bursts of power by hand pumping the primer, which kept him in the air long enough to clear a group of trees and make it to a small clearing just beyond them.

Powell jumped out of his plane and a farmer came after him. After firing a shot, the farmer ran away, and Powell took off in the other direction. Following his compass, he started heading west. His flight suit, with an 8th Air Force patch on one shoulder and a U.S. patch on the other, made it obvious he was an American.

It was cold, and the first night he encountered ice fog; he had to keep walking or he would freeze to death. Powell walked two days and two nights, many times passing groups of Germans, yet amazingly, no one challenged or stopped him.

He recalled one encounter that occurred in the middle of the night. He was walking down a road and came to a bridge guarded by a German soldier. He knew that if he stopped, the German would get suspicious, so he kept walking. The guard stamped his feet and blew on his hands in the cold. When Powell got close, he mumbled something that he hoped would sound German and kept on walking. As he strolled away, the German continued stamping his feet and blowing on his hands.

Powell came upon a marsh with trees on the other side, where he’d be able to hide. The trees were less than a quarter mile, but it took him six hours to cross the marsh.

He then encountered some children wearing wooden shoes, ice-skating on a frozen pond. After seeing Powell, they ran to a farmhouse. When a soldier ran out and started chasing him, Powell took off running, then heard shots. Hearing the rounds hitting the limbs above his head, he stopped and put up his hands. The Germans took him to a nearby Me-109 base. On Jan.16, 1945, two days after being shot down, he became a POW in Holland.

“That day I learned what it means to lose your freedom, and I knew then that freedom is not free,” said Powell.

Each of these aces knows the high price paid for our freedom, which, unfortunately, many people take for granted today.

For more information about the American Fighter Aces Association, visit [http://www.americanfighteraces.org].