Featured in 2005

“The Earth doesn’t tumble through space; it moves with logic and certainty and with beauty beyond comprehension,” said Capt. Gene Cernan. “It’s just too perfect and beautiful to have happened by accident. Someone, some being, some power placed our little world, our sun and our moon, where they are in the dark void.”

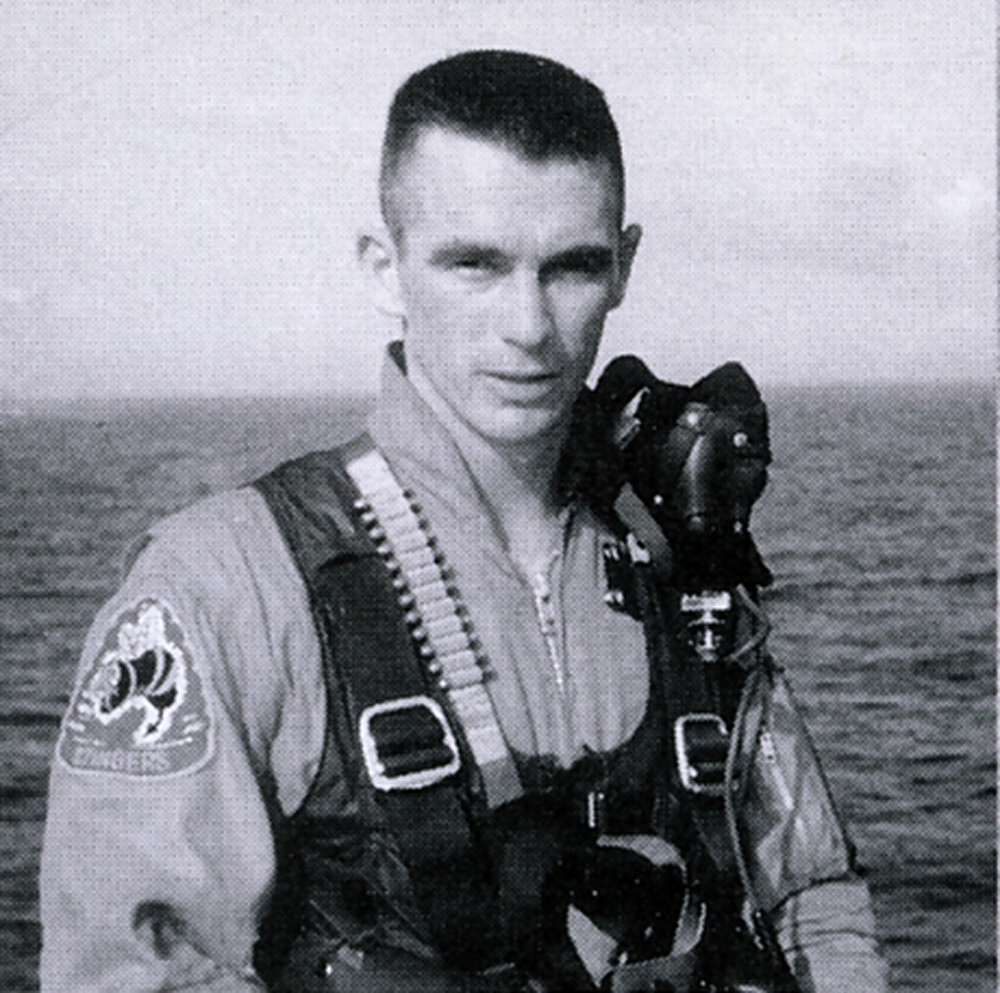

Cernan speaks about the earth’s beauty as a spectator who’s seen it from a place few have stood. And when he speaks about “our moon,” he does so as the last man to step foot on its surface.

But in the early 1960s, the moon was the last thing on Cernan’s mind. In the spring of 1963, Cernan finished his two years at the Naval Postgraduate School, earning him a master’s degree. His plan was to get an advanced degree in aeronautical engineering at Princeton, giving him a chance of an assignment to the Navy’s test pilot school at Patuxent River, Md. But in June, he received a call from a commander with the Navy’s Special Projects Office in Washington.

“He said, ‘We want to recommend you to NASA for further evaluation,'” Cernan recalled.

The call was a complete surprise. An astronaut applicant had to be a graduate of test pilot school, have two years of experience as a test pilot in at least 20 major types of aircraft, have at least 1,500 hours of jet time and hold a bachelor’s degree in engineering or the equivalent. Beyond that, he couldn’t be over 40 years of age, as of Dec. 31, 1959, stand more than 5 feet, 11 inches or weigh more than 177 pounds. Cernan hadn’t been to test pilot school and had only 1,300 jet hours, so he hadn’t volunteered for the space program. But he instantly knew his answer.

“I said, ‘Hell, yes!'” he recalled.

The Navy and Army had been reviewing other candidates for months. By the time NASA invited Cernan to interview in Houston, the original list of candidates had dwindled by more than 50 percent.

“About 400 people walked into the Rice Hotel in Houston,” he recalled. “I like to think 400 of the finest, best test pilots in the world were in that room—and me.”

Cernan soon hear he was one of 36 remaining candidates. Starting to feel more confident, he put Princeton plans on hold and decided to stay in Monterey and finish his thesis on using hydrogen as propulsion for high-energy rockets.

NASA’s next step was personal interviews with each candidate. The NASA team included several civilians, as well as Deke Slayton, Wally Schirra and Alan Shepard. Of the original seven astronauts, all but Slayton had flown during Mercury. Grounded because of a minor heart fibrillation, he became coordinator of astronaut activities in September 1962, responsible for the operation of the Astronaut Office.

When it came to final notification, it was known that if Slayton called a candidate, he was in, but if Warren North, Slayton’s assistant called, he wasn’t. One late October afternoon, Cernan and Evans were both called to the dean’s office.

“I got the call from Deke,” Cernan said.

NASA soon announced the names of the newest astronauts. The third group of astronauts (“The Fourteen”) included Lt. Cernan, Lt. Alan L. Bean, Lt. Roger B. Chaffee and Lt. Cdr. Richard F. Gordon Jr. from the Navy; Air Force officers Maj. Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Capt. William A. Anders, Capt. Charles A. Bassett II, Capt. Michael Collins, Capt. Donn F. Eisele, Capt. Theodore C. Freeman and Capt. David R. Scott; and Capt. Clifton C. Williams Jr. from the Marines. Two civilians, R. Walter Cunningham and Russell L. Schweickart, completed the list.

When President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, Cernan wasn’t the only one wondering about the future of the space program.

“No one was sure what was going to happen without Kennedy’s leadership,” he said.

As President Lyndon B. Johnson began leading the country, the space program forged ahead. Gemini, a two-man program, bridged the Mercury and Apollo programs.

“Apollo had been defined,” Cernan said. “Gemini filled the gaps of things we had to learn to get to Apollo, like how to walk in space and how to rendezvous.”