Di Freeze

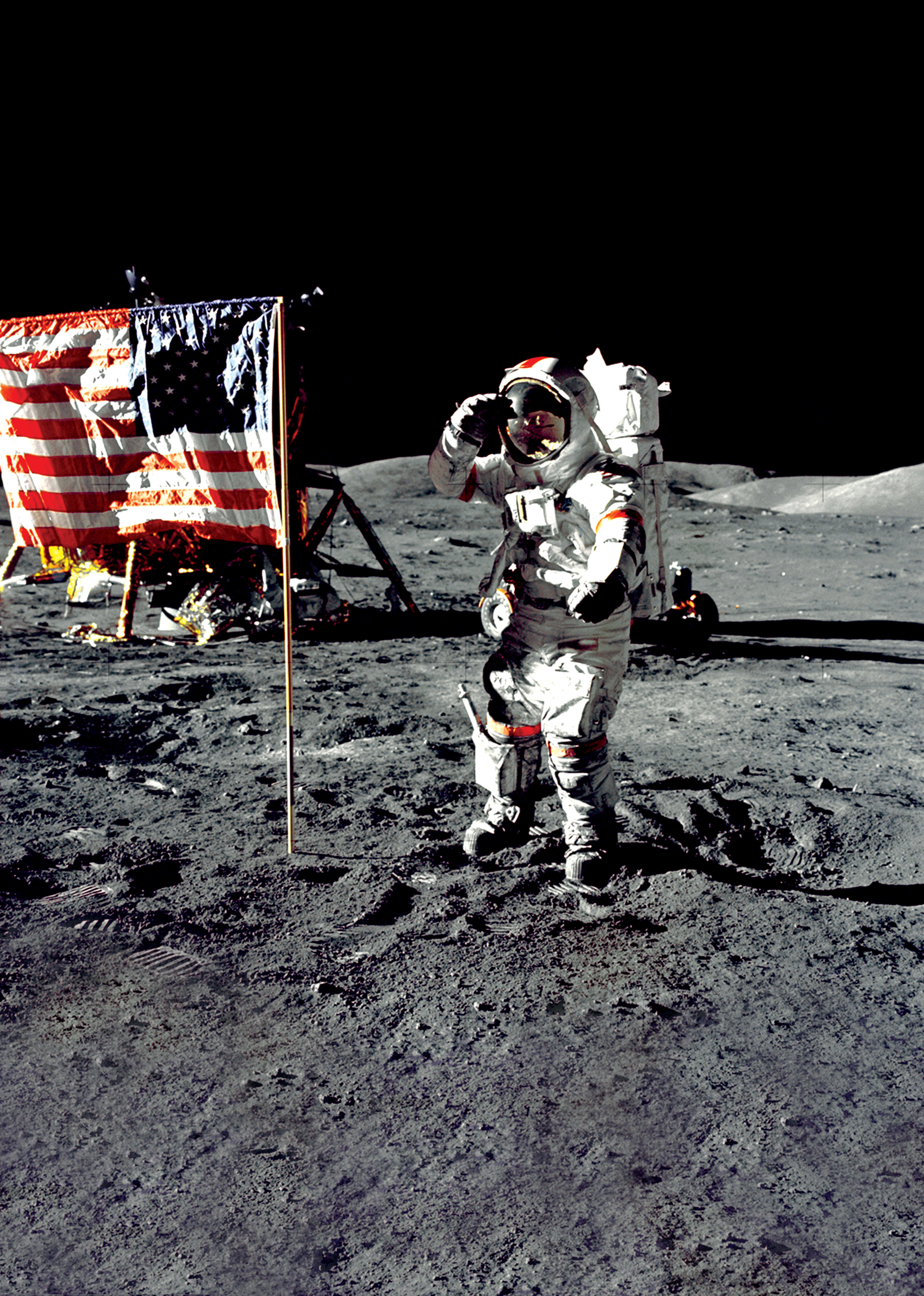

After coming back from his historic flight on Apollo 17, astronaut Eugene Cernan answered a lot of questions; one was particularly irritating. It was, “How does it feel to be the tail of the dog—the last one over the fence?”

After coming back from his historic flight on Apollo 17, astronaut Eugene Cernan answered a lot of questions; one was particularly irritating. It was, “How does it feel to be the tail of the dog—the last one over the fence?”

“I got on my soapbox at Kennedy when we got back,” he said. “I said, ‘Apollo 17 is not the end! It’s just the beginning of a whole new era in the history of mankind. We’re not only going back to the moon; we’re also going to be on our way to Mars by the turn of the century.’ I believed it then and I believe it now; my timetable is just a little off.”

Cernan has a new prediction.

“Unfortunately, it’s going to be 12 to 15 years before we go back to the moon, and it’s going to be a couple decades before we go to Mars,” he said. “We had the capability to go to Mars by the turn of the century. We just turned our backs on it.”

Gene Cernan describes himself as an “ordinary guy who’s had a chance to do some unordinary things in his life.” When he made that comment to a good friend once, the response was, “But other people look at you differently than you look at yourself.”

Judging by the fact that people constantly still come up to him and ask to shake the hand of someone who actually walked on the moon, that person was right. Cernan’s repeatedly been asked to tell his story, especially what it was like taking those last steps on the moon. Being able to answer everyone’s questions was a big reason he wrote “The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America’s Race in Space.” Published in 1999, the intriguing story was written with Don Davis.

“People want to know, ‘How did it feel? What did it look like? Were you scared? Did you feel any closer to God?'” he said. “Even if you get tired of hearing yourself talk, you have a responsibility to answer these questions.”

The book takes readers through Cernan’s life, as well as through the history of America’s race against the Soviet Union to reach the moon.

Eugene A. Cernan’s story begins on March 14, 1934, in Chicago, when the second-generation American, of Czech and Slovak descent, was born to Andrew George and Rose Cernan. While he was growing up, the Cernans, a “blue-collar family,” lived in Bellwood and Maywood, Ill., suburbs of Chicago.

Often, after a trip to the local movie theater, the young boy would daydream about what he wanted to do when he grew up.

“When I was in elementary school, my dad would try to take us to a movie once a week,” he recalled. “We saw all these war movies. And then the Movietone news—black and white newsreels of the war—would tell you what was really going on, what the Joe Fosses of the world were really doing out there.”

Between the movies and the news, like other children of the time, he decided he wanted to fly.

“But I put a condition on it,” he said. “I wanted to fly airplanes off aircraft carriers. I thought that would be the greatest challenge in the whole world. That was something I kept in the back of my mind all through school.”

He eventually did reach his goal. While in the Navy, Cernan made 206 carrier landings, of which 32 were made at night.

“By today’s standards, that’s not very many,” he said. “But they were all on a smaller carrier, which makes it a little bit more interesting.”

To this day, he says that nothing he’s ever done—including landing on the moon—compares to a night carrier landing.

“That’s where you find out who you really are—you and your maker on a foggy night, in the middle of an ocean somewhere, nowhere else to go,” he said.

Headed toward that dream

Although that was his dream, while growing up other things did catch Cernan’s interest. By his senior year at Proviso High School, in Maywood, he played varsity football, basketball and baseball. Scholarships to Dartmouth and maybe Duke looked possible.

The Korean War started as he became a senior; Cernan continued to dream of being a naval aviator, if he was called on to serve. However, he was intent on entering college, which was his father’s dream.

“Dad barely finished high school and Mom didn’t go to college either,” he said. “He wanted my sister Dolores and me to both go to college and get the education he never had a chance to get.”

In particular, he wanted his son to be an engineer.

“When I was in high school, I was a good student in science and math; it just seemed like a natural thing to do,” Cernan said.

Andrew Cernan wanted his son to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but that was financially unattainable. His next choice, and Gene Cernan’s first choice, was Purdue University, in nearby Indiana.

At the start of his senior year, Cernan applied for a Naval ROTC scholarship, and was accepted. Passing with a high score, he signed up for the NROTC program at Purdue.

Although Cernan was awarded a full-ride scholarship that included spending money, three summer cruises and graduation in four years as an ensign in the regular Navy, Purdue’s Naval ROTC slots were full. He instead applied to the University of Illinois, and was accepted.

“It’s a good school, but my dad adamantly wanted me to go to Purdue,” he said.

The Navy also offered a partial scholarship at Purdue, which mainly covered expenses during the junior and senior year, and led to a commission in the naval reserve. Cernan was reluctant to accept it, knowing that his family would be footing the rest of the bill, but at his father’s insistence, he took the reserve scholarship.

He headed to Purdue after graduating from Proviso High in June 1952. To help pay for room and board, he waited tables in the residence hall, before and after joining Phi Gamma Delta.

“A couple small scholastic scholarships also helped along the way, but Mom and Dad basically foot the bill,” he said.

Cernan’s grades and service record put him in line to become commanding officer of Purdue’s NROTC unit, but since he wasn’t in the regular Navy program, he had to settle for being executive officer in his senior year. That reserve commission also made him wonder if he had a realistic chance for flight school.

During the summer of his junior year, the reserve midshipman headed for Norfolk, Va. There, he boarded the “USS Roanoke” for a required cruise, which would take him around the Caribbean and to Puerto Rico. He had been disappointed to find that there were no planes onboard, but he would at least soon experience his first flight. He took a train to Chicago when the cruise ended; when his vacation was over, his father bought him a ticket back to Purdue aboard a Lake Central Airlines DC-3. His first flight wasn’t the thrill he had anticipated, but the next one—a ride in a fraternity brother’s small Cessna 152, including a try at the controls—was.

With a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a 5.1 grade point average, Cernan graduated from Purdue on June 6, 1956, and was commissioned as an ensign in the United States Navy (Reserve). He was also accepted into flight school.

“Sure, baby, I fly jets”

That summer, he reported to Pensacola, Fla., for duty aboard the “USS Saipan” (CV-48). When several career officers onboard encouraged him to apply for the regular Navy, he did and was accepted. He began flight training in January 1957, and soloed less than a month later, in a T-34, with 11 hours of training.

After they had logged 30 hours, students went on to either multi- or single-engine training.

“There was no question where I wanted to go,” he said. “I wanted single-engine jets. That didn’t mean you were going to get it. They gave some guys their choices to start with, and then when they had to fill up the blanks on both sides, they just put you where they wanted you. Fortunately, I got through primary with pretty good flying skills, so I got my choice.”

Cernan went on to Whiting Field, where he would fly the T-28 for the next six months. After about 100 hours of cockpit time, he was transferred to Baron Field, Pensacola. From there, he was to go back aboard the “Saipan,” this time as a pilot. After carrier qualification, he would be shipped off to Corpus Christi, Texas, for advanced training that eventually would lead to flying jets.

But that all changed when the Navy decided to up a naval aviator’s commitment from a minimum of three to five years.

“A lot of guys said, ‘No, I don’t want to stay in that long,’ and dropped out of flight training at that point in time,” Cernan recalled. “I wasn’t married and had no responsibilities; I jumped on the bandwagon.”

When the Navy ran out of students at the Memphis Naval Air Station, they looked Cernan’s way.

“They said, ‘You and you and you just volunteered,'” he said. “They picked about six or seven of us and sent us up to Millington Field.”

Less than a month after going to Memphis, Cernan was in the cockpit of a jet fighter.

“They put us through all-weather, and then we transitioned to the T-33,” he said.

His mother pinned the wings of gold on his dress blue uniform on Nov. 22, 1957, 10 months after he had begun to fly, instead of the normal 18. Ironically, he hadn’t yet finished flight training nor landed on a carrier.

“At that time, they were giving you your wings of gold after you qualified for all-weather flight,” he said.

Cernan returned to Pensacola after Christmas 1957, with the rank of lieutenant (junior grade). He was soon flying a single-seat F9F Panther, a Korean War vintage jet fighter.

He finished flight training in February 1958. Graduating third in his class earned him his choice of assignments. He chose the West Coast, because he liked the idea of touring exotic Asia. And he selected single-engine jet attack.

“It sounded much better to go attack the enemy than to just fight them when they come to attack you,” he grinned.

In February 1958, he headed for San Diego, home of the Miramar Naval Air Station, Fightertown U.S.A., or “Top Gun.” With an initial job of squadron duty officer, he was soon assigned to Attack Squadron VA-126 (call sign “Tough Guys”).

“When I got orders to the fleet, I’d still never been aboard an aircraft carrier,” he said. “Here I was, a nugget, out in the fleet—you know, ‘Sure baby, I fly jets,’ that kind of thing—but I’d never been aboard an aircraft carrier.”

That was rectified when Cernan, recently flying the swept-wing F9F-8 Cougar and the FJ4-B Fury, was told to fly an A-4 Skyhawk, a small single-engine attack plane, out to the “USS Ranger” (CVA-61) to finally obtain his carrier qualifications.

In November 1958, he was reassigned to VA-113, part of Air Group 11 on the “USS Shangri-La.”

“I was part of a group of about half a dozen pilots that were training to replace pilots that were leaving VA-113, once they came back from a cruise to the Western Pacific,” Cernan said. “They were the first ones to take A-4s out on a cruise.”

Cernan set out on his first WestPac cruise in March 1959. In the Straits of Formosa, they frequently encountered flights of MiGs.

“The Chinese were flying in one direction and we were flying another,” he said. “The carrier would cruise from north of Japan all the way down to south of Hong Kong, Singapore and those areas. The A-4 could carry a big, big nuclear bomb. Should the bell ring, we all had major targets, whether it would be an air field near Shanghai or a dock in Vladivostok, or wherever.”

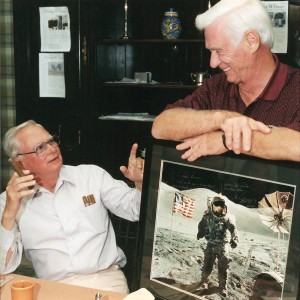

Gene Cernan, the last man to walk on the moon, shares a light moment with good friend and fellow aviator Barron Hilton, on one of Cernan’s past trips to Hilton’s Flying M Ranch.

After a tour as skipper of the Blue Angels, Zeke Cormier was the air group commander of four squadrons, as well as the air group boss aboard the “Shangri-La.” Cernan was one of three nuggets Cormier chose to “teach” how to fly. The others were Fred “Baldy” Baldwin, Cernan’s good friend and roommate, and Dick “Spook” Weber.

“That was absolutely great flying,” Cernan said. “He taught us everything that he learned in the Blues.”

They called themselves the Albino Angels until they were told to change the name to avoid conflict with the Blue Angels.

“We changed it to the Stingers, which was the call sign for our squadron,” he said.

The Stingers put on precision demonstrations throughout Asia.

Love, marriage and space

The “Shangri-La” returned to San Diego on Oct. 2, 1959, and was subsequently transferred to the East Coast. Cernan’s air group would be going aboard the “USS Hancock.”

While catching a flight out of Los Angeles International Airport back to Chicago for Christmas, Cernan met his future wife, Barbara Atchley, a Continental Airlines stewardess whose main runs were to Chicago. Born in Texas, Atchley lived in Redondo Beach, Calif.

Lt. Cernan left for his second WestPac tour in June 1960, and returned in March 1961. That May, Cernan and Atchley were married in the tiny chapel at Miramar. The day before the wedding, at Cape Canaveral in Florida, Alan B. Shepard, a naval aviator, blasted off for a 16-minute suborbital flight that carried him to an altitude of 116 statute miles. The flight was the U.S.’s response to Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who, on April 12, aboard Vostok 1, became the first man in space, flying a single orbit during a flight of 108 minutes.

“That was the first time I ever really paid a lot of attention to what might be going on in the space program,” Cernan said. “Someone asked me, ‘How would you like to do that someday?’ I said, ‘By the time I get good enough, or by the time I get qualified, there won’t be anything left to do. All the pioneering will be over.'”

A month before Cernan had donned his wings, Sputnik became the first manmade object ever to reach orbit. On Nov. 3, 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik 2 into orbit with “Laika,” a dog, as a passenger.

A year later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was formed, replacing the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics. NASA selected the first seven astronauts, all veteran test pilots, in April 1959. The Mercury series astronauts were Shepard, M. Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper, John H. Glenn Jr., Virgil “Gus” Ivan Grissom, Walter M. Schirra and Donald K. “Deke” Slayton.

A NASA astronaut applicant had to be a graduate of test pilot school, have two years of experience as a test pilot in at least 20 major types of aircraft, have at least 1,500 hours of jet time, and hold a bachelor’s degree in engineering or the equivalent. Beyond that, he couldn’t be over 40 years of age as of Dec. 31, 1959, stand more than 5’11”, or weigh more than 177 pounds.

Cernan met two of the requirements. But it really didn’t matter to him.

“I was doing my thing,” he said. “I was doing the kind of flying I wanted to do.”

And he was a busy newlywed preparing to move into a cottage in Del Mar, Calif. But the space program caught his attention again when, within three weeks after Shepard’s flight, President John F. Kennedy challenged the nation to commit itself to the goal, before the decade was out, of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade…not because this will be easy, but because it will be hard,” he said.

“He was asking us to do what most people thought couldn’t be done,” Cernan said. “We had a grand total of 16 minutes of space flight experience.”

With his five-year commitment up that June, Cernan had been thinking about getting out of the Navy.

“The Navy said, ‘Why don’t you think about staying around and we’ll send you to post-graduate school in Monterrey,'” he recalled. “I said, ‘What the hell? I don’t know what else I’m going to do to make a living, and I could still fly. Not as much, but I could still keep my hand in it.”

At the Naval Post Graduate School, Cernan could earn a master’s degree in a two-year program, with an option for a third year at a major university. After getting an advanced degree in aeronautical engineering, there was a good chance he would be assigned to the Navy’s test pilot school at Patuxent River in Maryland.

“That’s what I had on my agenda,” he said.

After that, he thought, he could return to the fleet and be in line for a squadron command of his own. Between July 1961 and May 1963, as Cernan attended school, a lot happened within the space program.

On July 21, 1961, Gus Grissom’s 15-minute suborbital Mercury test flight aboard the Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft ended in near disaster when the hatch blew off after he landed in the water. When the third Mercury flight launched on Feb. 20, 1962, John Glenn became the first American to reach orbit.

In September of that year, another group of astronauts joined the “Original Seven.” The “Next Nine” included civilians Elliot M. See Jr. and Neil A. Armstrong; Air Force pilots Frank Borman, James A. McDivitt, Thomas P. Stafford and Edward H. White II; and naval aviators Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr., James A. Lovell and John W. Young.

Scott Carpenter flew the second American manned orbital flight on May 24, 1962. On Oct. 3, 1962, Wally Schirra made a six-orbit flight, which lasted 9 hours, 15 minutes. On May 15-16, 1963, Gordon Cooper accomplished a 22-orbit mission that concluded the operational phase of Project Mercury. During the 34 hours, 20 minutes of flight, Faith 7 attained an apogee of 166 statue miles and a speed of 17,546 miles per hour and traveled 546,167 statue miles.

“That was big-time stuff,” Cernan said. “We were chasing the Russians. They were doing relatively spectacular things in that environment at that time.”

Cernan watched what was going on in the space program with interest, but there were plenty of things going on in his own life that kept him preoccupied. On March 4, 1963, Teresa (“Tracy”) Dawn Cernan was born. Later that spring, Cernan finished his two years at Monterey, and started planning for his third year of advanced study at Princeton.

That summer, he began as an intern with Aerojet General in Sacramento, where he worked on advanced liquid rocket propulsion systems. In June, on a Friday afternoon, he received a call from a commander with the Navy’s Special Projects Office in Washington.

“He said, ‘We’ve been screening Navy people; we want to recommend you to NASA for further evaluation.’ Like a dummy, I said, ‘For what?'” Cernan recalled. “I hadn’t volunteered for the space program, because I hadn’t been to test pilot school and I didn’t have enough jet hours.”

At 1,300 hours, however, he was only 200 short. It finally sunk in that those things didn’t seem to matter.

“I not only said ‘Yes,” I said, ‘Hell, yes!'” he recalled.

Although puzzled, he knew that things in his favor included a good operational record and a good education.

“The two cruises I made went well,” he said. “I had some very good recommendation from a couple skippers and people like Zeke Cormier, along the way. Unknown to me, the Navy and the Air Force had been reviewing potential candidates for several months.”

Told that his answer was required in writing by Monday morning, Cernan sent his response by telegram.

“That’s when things got exciting,” he said. “They’d send a whole ream of stuff to fill out, essays to write. And then it’s, ‘Don’t call me. I’ll call you.'”

When NASA invited him to interview in Houston, the sight of the new Manned Spaceflight Center, he learned that the original list of candidates had been cut by more than half.

“About 400 people walked into the Rice Hotel in Houston,” he said. “I like to think there were 400 of the finest, best test pilots in the world in that room—and me.”

Included in that group, none of whom checked in under his own name, were three of his classmates: Bob Schumacher, Ron Evans and Dick Gordon, a well-known test pilot who had just missed the cut for the second group of astronauts.

“It was a big secret type thing,” Cernan said. “We had about four or five days of more testing, preliminary physicals, and more questions; I knew nothing about orbital mechanics, or satellites, or any of that stuff.”

After he returned to Monterey, he learned he had made another cut. There were now 36 candidates.

“Now, all of sudden, it’s, ‘Hey, I might really get chosen,'” he recalled. “But we didn’t know how many people would be chosen. We lost four to physicals.”

Starting to feel more confident, Cernan revised his plans for Princeton.

“That was the biggest gamble I ever took,” he said. “When you left Monterey after two years, you didn’t have a master’s degree. So, not knowing whether I was going to get selected or not, had I gone to Princeton and somehow got pulled out, then I would’ve got nothing out of it.”

Since Monterey was just opening new propulsion laboratories, Cernan decided to stay there and finish his thesis on using hydrogen as propulsion for high-energy rockets.

“If I wasn’t selected, I’d at least be able to finish my third year, right there,” he said.

The next step was personal interviews with a team that included several civilians, as well as Slayton, Schirra and Shepard. Of the Original Seven, all but Slayton had flown during Mercury. Grounded because of a minor heart fibrillation, he became coordinator of astronaut activities in September 1962, and was responsible for the operation of the Astronaut Office.

“I remember someone asked me, ‘How many times have you been above 50,000 feet?'” Cernan recalled. “I said, ‘I’ve been flying A-4s; I’ve been up there once.’ You don’t know what they’re looking for. I didn’t mean to be smart ass, but I said, ‘I’ve been flying mostly below 100 feet. I’ve been flying attack aircraft off of carriers, so I’ve been flying close to the ground. If you’re going to land on the moon, you’ve got to get close to it sometime!'”

When it came to final notification, it was known that if Slayton called you, you were in, but if Warren North, his assistant called, you weren’t. Early one late October afternoon, while Cernan and Ron Evans were both at school, they were simultaneously called to the dean’s office.

“They said, ‘Ron, you have a call in this room and Geno has a call in this room,'” Cernan remembered. “We knew one of us didn’t make it. I got the call from Deke.”

NASA soon announced the names of the 14 newest astronauts. From the Navy were Lt. Cernan, Lt. Alan L. Bean, Lt. Roger B. Chaffee and Lt. Cdr. Richard F. Gordon Jr. Representing the Marines was Capt. Clifton C. Williams Jr. Air Force officers included Maj. Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Capt. William A. Anders, Capt. Charles A. Bassett II, Capt. Michael Collins, Capt. Donn F. Eisele, Capt. Theodore C. Freeman and Capt. David R. Scott. Two civilians, R. Walter Cunningham and Russell L. Schweickart, completed the list.

But on November 22, when President Kennedy was assassinated, Cernan wasn’t the only one wondering about the future of the space program.

“No one was sure what was going to happen without Kennedy’s leadership,” he said.

Houston

But the space program forged ahead. Gemini, a two-man program, would serve as a bridge between the Mercury and Apollo programs.

“Apollo had been defined,” Cernan said. “Gemini came into being to fill in the gaps of things we had to learn to get to Apollo. That was all earth orbit as well, but we had to learn how to walk in space and how to rendezvous.”

They also had to keep an eye on the Russians. Shortly before Cernan’s astronaut class came on board, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space. Before Cernan could even think about what was in store for him in the space program, he had to get his family moved to Houston, by Jan. 15, 1964. He accomplished that task just days after a private graduation ceremony.

When the Cernans arrived in Texas, the Manned Spaceflight Center was in the process of being built.

“We moved in, but it was another six months to a year before it ever really became operational,” he said.

Around the center were three separate neighborhoods housing most of the astronauts. Timber Cover was home to six of the Original Seven; most of the Next Nine owned houses at El Lago. Cernan’s group took up residence mainly in the newer settlements of Clear Lake and Nassau Bay.

The Cernans initially rented a house in Clear Lake, a subdivision southeast of Houston. As Cernan settled into his new role, everyone waited to see what President Lyndon B. Johnson would do. But the “freshmen” began their classroom work, knowing that it was already being decided who was going to fly the first Gemini flights.

Slayton, who had resigned his commission as an Air Force major to assume the role of director of flight crew operations for NASA, would make the decision, with the help of Shepard, whom he had appointed as chief of the Astronaut Office.

“Deke was our ‘godfather,'” Cernan said warmly.

His first impressions of Shepard were slightly different; although he could be warm and personable one moment, he could also be “ice-cold” and “abrasive.” Cernan said Slayton and Shepard were good at playing “good-cop/bad-cop.”

“Deke instilled confidence and Al demanded more than your very best; the result was a better program,” he explained.

Two unmanned and 10 manned Gemini flights were planned. Five of the Mercury astronauts were still on flight status: Shepard, Grissom, Schirra, Cooper and Carpenter. Initially announcing one crew at a time, Slayton paired Shepard with Tom Stafford for Gemini 3.

But in the middle of 1963, before the assignment became official, Shepard was temporarily grounded due to an inner ear problem. Returning to flight status a few months later, he was assigned the Gemini premiere, but the ear condition worsened and he was vetoed from venturing into space.

Slayton then assigned Grissom to command Gemini 3, with Frank Borman as his crew, bumping Stafford to backup pilot. Schirra became Grissom’s backup. Cernan said the switches were just the beginning of an episode that “took on the mind-boggling confusion of the Abbott and Costello ‘Who’s on first?’ routine.” Shortly after that, Borman was scratched from Grissom’s crew in favor of John Young, who had originally been Schirra’s crewmate.

“There were another dozen or so pieces to that puzzle, but this single confusing incident illustrates the quirkiness of the entire crew selection process,” Cernan said.

The newest astronauts studied the choices being made with great interest.

“I think the 14 of us just figured, ‘There’s not a chance of us ever getting to fly in Gemini,'” he said.

The “Fourteen” went about their new life, which included a brief orientation, followed by 20 weeks of classroom lectures, technical assignments, and field trips to desolate regions such as the volcanic territory in Arizona, Alaska and Iceland. Each new astronaut was assigned to a specialty to support the pair of unmanned Gemini test flights that would lead to Gemini 3. Because of his academic background, Cernan would be monitoring the propulsion systems.

“I was assigned to work at Mission Control during Gemini 1, 2, 3 and 4,” he said. “That wasn’t on a daily basis, but when the flights were coming up.”

The first two Mercury astronauts had ridden an old Redstone rocket, and the others a more powerful Atlas. The first unmanned test launch using the Titan, a liquid fuel rocket, as a Gemini booster rocket, took place April 11, 1964.

First tragedy and new blood

As time went on, Slayton announced Jim McDivitt as commander and Ed White as pilot on Gemini 4, with Borman and Jim Lovell as their backups.

The space program suffered its first astronaut fatality in October 1964, when a goose smacked into the canopy of a T-38 being flown by Ted Freeman, while he was setting up a routine landing approach. Damage to the canopy forced Freeman to punch out, but his parachute didn’t have time to open properly.

In mid-January 1965, Gemini 2 made a successful test of 18 minutes. During the flight, Cernan was given the job of “tanks.”

“The pressure on the fuel and oxygen tanks was very critical on the Titan, because it was an intercontinental ballistic missile,” he said. “We had to put special gauges in the spacecraft to monitor that.”

The next month, Slayton announced that Gordon Cooper would command Gemini 5, with Pete Conrad as pilot, and Armstrong and Elliot See as backups. In the battle for space, Voskhod 2 launched on March 18; Alexei Leonov became the first person to walk in space. His walk lasted 12 minutes.

Five days later, on March 23, Cernan worked tanks again for Gemini 3; Grissom and Young made three orbits. Following their job as backup on Gemini 3, Schirra and Stafford rotated to prime for Gemini 6.

Gemini 4, the first flight to be handled out of Mission Control in Houston, took place June 3-7. White, the first American to walk in space, was outside for 21 minutes, controlling himself in space during extra-vehicular activity with an astronaut maneuvering unit.

A new group of six astronauts were soon announced. All scientists, they were Owen K. Gariott, Edward G. Gibson, Duane Graveline, Lt. Cdr. Joseph P. Kerwin, F. Curtis Michel and Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt.

Shortly after that, Slayton announced that Borman and Lovell would be the prime crew for Gemini 7; Mike Collins and Ed White were their backups. Neil Armstrong would command Gemini 8, with Dave Scott as pilot, and Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon as backup.

Elliot See would command Gemini 9, with Charlie Bassett as pilot. Although their backup crew wasn’t announced, a three-mission rotation scheme had unfolded. If it held true, the prime crews could be projected all the way through Gemini 11. That didn’t leave much hope for the others still wishing for a Gemini mission.

The Fourteen concluded that the Gemini 9 backup pilot slot was the only prize left for them. Whoever got that job could rotate onto the prime crew for the last mission.

Gemini 5 launched on August 21 for an eight-day, 120-revolution mission. Cooper and Conrad traveled 3,312,993 miles in an elapsed time of 190 hours and 56 minutes. Cooper also became the first man to make a second orbital flight.

Shortly after that, Cernan, sharing an office in the new MSC complex with Armstrong, received some exciting news.

“There was a subtle way of saying, ‘You’re going to get assigned to a crew,'” he recalled. “You were told, ‘Go get fitted for a suit.’ I was told to do that. Then Deke got a hold of me and said, ‘You’re on the backup crew with Stafford in Gemini 9.'”

The official announcement came on Nov. 8, 1965. Stafford, at the time working on Gemini 6, which was experiencing delays, would be the backup commander. Cernan began working in earnest with See and Bassett.

For Gemini 6, it was planned that an unmanned Agena rocket would be launched and parked in a drifting orbit. Then, a Titan bearing the spacecraft with Schirra and Stafford aboard would launch, chase down the Agena, and dock with it. But on the launch day of Oct. 25, the Agena blew up before reaching orbit, forcing the flight to be scrubbed until a new target could be found.

It was eventually decided to launch Gemini 7 first. On Dec. 4, 1965, Borman and Lovell were launched into space on a flight that would last 330 hours and 35 minutes. On Dec. 15, with Schirra occupying the command pilot seat, Gemini 6 successfully rendezvoused with the already orbiting Gemini 7 spacecraft, accomplishing the first rendezvous of two manned maneuverable spacecraft.

Another tragedy

Cernan continued working hard on his backup work. He paused to celebrate, however, when he heard good news. After only nine years in total service, and five years in grade as a lieutenant, the Navy promoted the 31-year-old astronaut to the rank of lieutenant commander.

Gemini 9, being built at the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, was to fly into orbit in May 1966, join up with an Agena rocket, light off the Agena engine, to push into deeper space, and perform several complicated rendezvous procedures. Then the crew would move to a new realm of tests.

Bassett would do a spacewalk, wearing the astronaut maneuvering unit, on an extra-vehicular activity, connected to the spacecraft by only a long, thin tether. The AMU, which the Air Force had been developing for seven years, looked like a massive suitcase.

“It was truly Buck Rogers; it was ahead of its time,” Cernan said.

The astronaut would sit on a small bicycle-type seat, strap on the AMU and glide off into space, maneuvering with controls mounted on the armrests.

While he worked on Gemini 9, Cernan spent many off-duty hours with Bassett as well. Charlie and Jeannie Bassett lived about three blocks from the Cernans, and the two couples often shared dinners and long talks.

Cernan would soon add another astronaut friend to the growing circle. After missing his first bid to become an astronaut, Lt. Cdr. Ronald E. Evans Jr. had earned his degree in Monterey and returned to the fleet, before heading out for Vietnam, where he flew more than 100 combat missions. Now, he was included in a new round of 19 astronauts that had come onboard.

But tragedy was just around the corner. On Feb. 28, 1966, See, Cernan, Bassett and Stafford climbed into a pair of NASA dual-seat T-38s to fly to St. Louis and spend time in the simulator at the McDonnell plant. The lead plane, NASA 901, took off at 7:35 a.m., from Houston, flown by See, with Bassett in the back seat.

“Stafford and I flew on their wing,” Cernan recalled.

As they rose up over Ellington, Stafford edged into position on See’s wing. By the time they began their descent at Lambert-St. Louis Municipal Airport, about nine o’clock, the weather had turned bad, including heavy fog.

“We were flying in formation, but we were too high and too fast and couldn’t get below the clouds,” Cernan said. “They broke off to land visually. Stafford and I went out and came back to make another approach and landed 15 minutes later.”

Cernan and Stafford were circling 20 miles away when, unknown to them, See and Bassett crashed into the top of Building 101, sitting 500 feet from the runway and housing the remaining Gemini spacecraft. As the aircraft cart-wheeled into the parking lot and exploded, both men were thrown from the plane.

Although the line of Gemini spacecraft being assembled in the building escaped damage, the space program lost two more astronauts. At first, no one knew who those two astronauts were.

“They had a specially-fitted baggage pod on their T-38,” Cernan said. “We threw our briefcases and whatever clothes we were going to wear in that pod. Once the airplane blew up, there was stuff all over the place. When people were picking up the ID badges and whatever else that we had in our briefcases, they’d find names of four different people. They had no idea until we landed who was in the airplane.”

Later that day, Slayton told a heavy-hearted Cernan and Stafford that Gemini 9 was theirs. As they moved up to prime, Lovell and Aldrin became the new Gemini 9 alternate crew; the change put them in line to make the final flight of the series.

Only three weeks before, an unmanned Soviet spacecraft had made the first soft landing on the moon, so the program had to move ahead quickly, without Bassett and See. On March 16, 1966, Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott were launched into space on Gemini 8. Originally scheduled to last three days, the flight was terminated early due to a malfunctioning thruster. Although Scott’s spacewalk had to be cancelled, the crew performed the first successful docking of two vehicles in space, with an Agena rocket.

Gemini 9

On May 17, after a medical check, Cernan and Shepard had the traditional launch-day breakfast of steak and eggs, and some last-minute mission talk. After breakfast, Cernan went to a private mass and communion.

Later, with Slayton, Cernan and Stafford left the crew quarters on Merritt Island, escorted by a convoy of police cars, crossed the causeway that spanned the Banana River, to cheering crowds, and entered the Air Force station launch area through tight security.

Cernan stepped out at a small trailer beside Pad 16, as the Atlas-Agena was being readied on nearby Pad 14. In the other direction, at Pad 19, was the Titan II, with their tiny Gemini spacecraft perched on its nose.

Once medics and technicians had finished sticking biomed sensors to their bodies, they were helped into their bulky suits. Cernan’s suit was different than Stafford’s for two reasons. First, he needed extra layers of insulation to protect him from the extreme temperatures he would encounter during his spacewalk. Those layers made his suit very stiff. Then, because of the AMU, he would be spacewalking with rockets blasting down “around his wazoo,” so he needed heat-resistant “iron pants.”

“My pressure suit was different because the AMU I was going to fly had hot gas jets—hydrogen peroxide—which would have burned through my suit if they impinged upon it,” he said. “The bottom of my spacesuit was woven steel wire, which made it doubly stiff.”

At one point, doctors insisted that Cernan remove the medal bearing the image of Our Lady of Loreto, and the legend, “Patroness of Aviation, Pray for Me,” from his neck, thinking the medal might cause interference with their sensors, but Slayton told him eventually to go ahead and wear it.

Cernan was concerned when a few hours before launch, Slayton called Stafford aside for a hushed conversation. Although it was unusual, and made him wonder if they were talking about the “rookie,” he soon forgot about it, at least temporarily. For the next three hours, they breathed pure oxygen to rid their systems of the nitrogen that might cause bubbles in their blood during a rapid change of altitude.

Then, for 45 minutes, they lay on couches in the trailer, slowly breathing and getting ready for the environment in which they would live for three days.

“If I was scared, I didn’t know it, because I was so excited,” Cernan said.

Then, with suit loops hooked to portable oxygen canisters, they waddled out to the van, as cameras clicked and flashed. At Pad 19, after riding the elevator up, they walked across the gangway, and went through a door into the clean area, known as the “White Room.” There, clad in long white coats and caps, waited Guenther Wendt and his closeout crew, as well as Lovell and Aldrin, to help Stafford and Cernan into a space no bigger than the front seat of a compact car—which they would be sharing with an instrument console the size of a small refrigerator.

The “morticians” guided them through the hatches. Technicians strapped them in and attached the oxygen and communications umbilical hoses to the spacecraft systems and armed the ejection seats. Guenther then flashed a thumbs up, which was part of his traditional good-luck benediction of wishing every astronaut “Godspeed.” Then the hatch was closed and locked from the outside.

In the meantime, Barbara Cernan expectantly waited in the home on Barbuda Lane in Nassau Bay that they had moved into after the Fourteen had started receiving their share of money from a contract with Field Enterprises Educational Corporation and Time, Inc., for exclusive rights to the astronauts’ stories. The deal became known as the “LIFE contract,” since most of the stories and pictures appeared in that weekly magazine.

Waiting with her were Cernan’s hunting buddy, Roger Chafee, his wife, Martha, and their two children; they had built a house on a lot next door. Also settled before a couple of TVs were her mother and several astronaut wives, while 3-year-old Tracy played with Amy Bean, the daughter of Al and Sue Bean.

Stafford and Cernan, plugged into the audio circuits, listened to the launch team go through the final Atlas-Agena countdown. If all went as planned, after the Agena reached orbit and kicked away its burned-out Atlas booster, it would return over the Cape on its first loop around the Earth. Exactly 99 minutes and nine seconds after it lifted off, as it coasted above Florida, Cernan and Stafford would launch to begin an 80,000-mile chase through space, catching it after three and a half orbits.

At 10:15 a.m., the Atlas-Agena lifted smoothly away from the Cape; 130 seconds later, it began to tumble. Ten seconds later the engines shut down, as planned, and the Agena separated, but it was too late, too low, and too fast, and the whole thing plunged into the Atlantic.

The flight would be postponed until June. Without another Agena ready to fly, NASA had turned to a McDonnell Aircraft Corporation creation that had been built after the Agena target vehicle had exploded during Gemini 6. The cheaper alternate docking target was officially named the Augmented Target Docking Adapter.

“We called it the ATDA, or the Blob,” Cernan said.

At 11 feet long and five feet in diameter, the front end looked much like an Agena, with a docking collar covered by a fiberglass cone that would be kicked off once in orbit. The main difference was that the Blob didn’t have the powerful Agena rocket engine they needed to raise their orbit to a higher altitude.

On June 1, although Stafford and Cernan awoke to black clouds, Hurricane Alma was still too far away to bother them. The Atlas blasted away from the Cape only three seconds behind schedule, and the Blob separated on schedule. Less than seven minutes after leaving the pad, it locked into an almost circular orbit. With a launch window of six minutes, Cernan and Stafford intended to catch up with the Blob over the Pacific, docking over the U.S. in broad daylight.

But as the ATDA crossed the California coast, a computer glitch resulted in the Blob zipping past silently overhead. The window of time passed, and the mission was once again scrubbed.

On June 3, the Blob once again sailed over the Cape. Although the same computer glitch happened again at the two-minute mark, Mission Control decided the launch was a go anyway.

As the first, and then the second stage engine kicked in, Stafford and Cernan were hurtled through a fireball. Eight minutes into the flight, they were pulling seven and a half G’s. When the rocket burned out a moment before they reached orbit, they went from having to struggle against an incredibly heavy weight, even to breathe, to zero gravity.

On their third orbit, flying through the night sky over the eastern Pacific, they spotted the Blob. Fifteen miles below and 126 miles away, they slowly closed the gap. Parking about three feet away, they discovered it was tumbling out of control, and that its conical nose shroud was still attached. Only the top one of a pair of thin steel bands holding it in place had sheared away. That allowed the forward end to spread apart, but the lower portion had stayed locked.

“We have a weird-looking machine up here,” Stafford radioed Houston. “It looks like an angry alligator.”

Ground controllers unsuccessfully sent up a stream of signals to try and open the still-covered docking collar and pry off the nose cone. Since they couldn’t reach the collar, it was decided to adopt an alternative flight plan that would have two more rendezvous maneuvers and contain no docking.

A second rendezvous exercise began after they had backed about 13 miles away. They eventually re-found the Blob, without radar. One of Cernan’s jobs was to use a pencil, a pad of paper, plotting tables, and a slide rule to figure some of the rendezvous calculations. Stafford made star sightings through sextant-like calibrations out his window.

By five o’clock that afternoon, Stafford and Cernan, who had been constantly dashing through daylight and dark, were exhausted. Mission Control told them to get some sleep. They woke up seven hours later, knowing the third and final rendezvous would be the toughest.

They were to simulate the procedures an Apollo command module pilot might have to employ to rescue a lunar vehicle stuck in a lower orbit. They would fly nose down and come in from above, trying to find the Blob, hidden somewhere in a bright background of the seas, clouds and land masses of Earth.

Although they could use the radar, there were serious doubts about some of the data being churned out by the computer. The tricky navigation would also have to be done by manual calculations. They saw the ATDA when they were within three miles of it, and completed that rendezvous.

The exercise took longer and burned more fuel than anticipated. With almost 685 pounds of fuel at launch, they now had only 52. That was barely enough to finish the mission, and they had a complex spacewalk and reentry left. The rendezvous had also been exhausting, so it was agreed to postpone the EVA until the third day.

While Stafford and Cernan slept, Mission Control discussed if the spacewalk should be canceled because of their physical state. When the astronauts awoke on Saturday, they found out the ground controllers had decided to abandon any further work with the ATDA. They were to spend the day drifting in space to conserve fuel, and primarily resting, although they would perform some minor experiments and take some pictures. The spacewalk was postponed until the next morning.

“The spacewalk from Hell”

Leonov’s spacewalk lasted 12 minutes; White’s lasted 21. Now, Cernan was going for a two-and-a-half-hour walk, highlighted by strapping on the rocket-powered backpack and scooting around the universe on his own.

On Sunday, after dropping to a lower orbit, Cernan strapped on his boxy chest pack, and plugged a 25-foot-long umbilical into the middle. It would feed him oxygen, communications, and electrical power, and relay information from medical sensors that could be monitored on the ground.

During their thirty-first revolution of the Earth, Cernan opened the hatch and climbed out of his hole. Standing on his seat, with half his body sticking out of Gemini 9 as they rushed along at about 18,000 miles an hour, he waited for the sun to come up over California.

His first chore would be to determine if a person could maneuver in space just by pulling on the long umbilical tether. Moving away from the protective shell of Gemini 9, his only connection with the real world was through the umbilical cord. The cord came to be known as the “snake,” since his slightest move not only affected his entire body, but also, rippling through the umbilical, jostled the spacecraft. The result was an “unwanted game of crack-the-whip.”

With nothing to stabilize his movements, Cernan continuously tumbled out of control.

“Even something like trying to unbend a kink in the umbilical would dangle me upside down or backward, and I was continuously tumbling in slow motion,” he said. “The only time I had any control at all was when I could grab tight just where the umbilical emerged from the hatch.”

When he would reach the end of the umbilical, he’d rebound like a Bungee jumper. If that wasn’t bad enough, the umbilical constantly tried to lasso him. The fight continued for about 30 minutes, until, needing a rest, he grabbed a small handrail and pawed his way back to the open hatch, where, exhausted, he paused to take in the incredible view of Earth.

Cernan needed to reach the rear of the spacecraft while he still had sunlight, to check out the AMU. That task wasn’t easy in his bulky, inflexible spacesuit. The bell-shaped Gemini package was made of two sections. When the second-stage rockets tore away after launch, they were left with the reentry module, which was their living and working environment; behind that was a larger section Cernan likened to a caboose on a train.

Designed to connect the reentry module to the rocket, the aerodynamic “adapter section” contained things like fuel cells, oxygen tanks and mechanical apparatus. His rocket pack was in the middle of a recessed area that was exposed at the bottom of the adapter section when the booster rocket was kicked away.

Cernan worked his way along a small railing, stopping periodically to hook the umbilical through small “eyes,” so that his line of life support would be steady and out of harm’s way. A jagged edge had been left all the way around the end of the adapter section when the Titan ripped away, so he carefully positioned the supporting wires just above the razor-sharp metal to prevent it from slicing his lifeline or his suit.

They entered darkness over South Africa as he swung around the rear of the adapter. Cernan was supposed to be wearing the AMU at dawn. Since the backpack’s arms were telescoped and folded, they needed to first be extended and locked in place. With the help of a small light, he unfolded the backpack’s restraining bars, and grabbed them tightly, as he was hauled through space at a speed of about five miles per second.

Barely able to see, he worked through the 35 different functions required to fly. In true zero gravity, it was a lot more difficult than it had been during Earth simulations. Cernan held tightly to the AMU’s restraining bar with one hand while working with the other.

“As soon as one end of me was stabilized, the other end tended to float away,” he said.

Many of the backpack’s valves and levers and dials were tucked away in hard-to-reach places.

“Every time I’d twist a valve, it would twist me back,” Cernan said. “It was a nightmare. My heart rate was running about 180 beats a minute.”

Eventually he flipped the final switch and the backpack powered up. But an hour and 37 minutes into his spacewalk, as he became the first human ever to circle the Earth outside a spacecraft, Cernan began having trouble seeing.

“While I was trying to get the AMU configured and ready to fly, I overpowered the Environmental Control System and my visor fogged up,” he explained.

Leverage remained one of his main problems. A couple of thin metal stirrups designed to hold his feet in place were inadequate.

“If Dave Scott had been able to go out on a spacewalk on Gemini 8, we probably would’ve learned a lot about the laws of motion—’For every action, there’s an equal, opposite reaction’—and about long duration outside spacecraft in zero gravity where you have no footholds or handholds or any way to position yourself,” he said. “But we didn’t learn any of that, so we sort of went out fat, dumb and happy.”

Cernan finally was strapped into the small seat. Then, he twisted and turned until he was finally able to exchange the umbilical connecting his chest pack to the spacecraft for the oxygen and power contained in the backpack itself, making him the first human to cut the secure lifeline to a spacecraft.

When Stafford reported to ground controllers, he informed them that the workload was four or five times more than what had been anticipated, that communications had degraded, and that Cernan wasn’t able to see through his visor. Cernan, whose heartbeat had almost tripled, was told to rest for a while. It was decided that if the situation didn’t improve, they wouldn’t proceed with the AMU.

Although he knew Stafford was being prudent, Cernan was disappointed that Mission Control now had a reason to scrub his flight with the backpack, and eventually did.

“In their expert opinions, things had gone haywire and I was in deep trouble,” he said.

But he had been so close!

“Tired as I was, I still wanted to go for it,” he said. “All Stafford had to do was throw a switch and I would’ve been out there flying on a 125-foot tether. It was extremely disappointing, because I felt I was sent up there to do a job. I know I could’ve done it, given half a chance. But in retrospect, it was probably good that we terminated when we did. I’m convinced I would’ve run into trouble.”

Still ahead of the hot and exhausted astronaut, who had just logged two hours and 10 minutes outside the spacecraft, were the tasks of getting out of the backpack and getting back into the spacecraft.

“To get out of it, I had to hold on to a little docking bar in front of the spacecraft with one hand and unbuckle everything with the other,” he said. “Think of trying to get the top off a Coke bottle with one hand. We were so naïve; in training in the zero-G airplane, we’d only get 25 seconds of zero gravity at a time. We weren’t able to propagate any of these problems.”

Cernan compared getting back into the small Gemini spacecraft, in his stiff suit, with putting a cork back in a champagne bottle. At six feet s around the hatch, lift it open, turn, and stick his feet inside. Stafford grabbed an ankle to anchor him. In the process, Cernan kicked the camera that Stafford had used to take pictures of his spacewalk. He tried to grab it, but it spun away, leaving them with only the pictures from a movie camera.

Cernan inched lower into the spacecraft, forcing his legs to bend into a duck-walk position. Excruciating pain shot through his legs as he pulled his body lower, twisting and managing to slide his heels over the edge of the seat while pushing his knees beneath the instrument panel.

Halfway in the spacecraft, his boots were now planted firmly against a steel plate that sealed the front side of the seat, toes pointed down; his legs were bent in a V position as he pressed down even further on them.

After managing to force his shoulders below the level of the hatch, Cernan bent his neck and head, and pulled on the hatch, but it hit the top of his helmet and wouldn’t close. Stafford was able to lower the hatch further, and jam it down another few inches, catching it on the first tooth of a closing ratchet. Finally, the hatch closed enough so that it couldn’t pop open.

Cernan couldn’t unfold his feet, which were still tight beneath him, nor could he push his torso any lower, since his knees were pressed hard against the underside of the panel. The hatch was finally locked tight, but he was in excruciating pain.

“If we can’t pressurize the spacecraft in a hurry and I have to stay this way for the rest of the flight, I’ll die!” he said.

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part II

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part III Finale