By Di Freeze

Mercury Astronauts, front row, L to R: Walter H. Schirra Jr., Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, John H. Glenn Jr., and Scott Carpenter; back row, Alan B. Shepard Jr., Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, and L. Gordon Cooper.

When 22-year-old Eugene A. Cernan graduated from Purdue University in 1956, with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, he received a commission as an ensign in the U.S. Navy (Reserve). His ambition was to fly off an aircraft carrier.

After being accepted into flight school, Cernan applied for the regular Navy, and was accepted. He began flight training in January 1957, and soloed less than a month later.

He received his wings of gold on Nov. 22, 1957, and finished flight training in February 1958. Graduating third in his class, he chose the assignment of West Coast, single-engine jet attack.

In February 1958, he headed for Miramar Naval Air Station, San Diego, where he was assigned to Attack Squadron VA-126. In November 1958, he was reassigned to VA-113, part of Air Group 11 on the “USS Shangri-La” and later the “USS Hancock.” He set out on his first WestPac cruise in March 1959, and as part of the Stingers, put on precision demonstrations throughout Asia flying the A-4. Lt. Cernan left for his second WestPac tour in June 1960, and returned in March 1961.

With an agenda of an assignment to the Navy’s test pilot school at Patuxent River in Maryland, followed by his return to the fleet and hopefully a squadron command of his own, Cernan attended Navy Post Graduate School, Monterey, Calif., from July 1961 to May 1963.

In the meantime, in April 1959, NASA selected seven Mercury astronauts—all veteran test pilots. In May 1961, Al Shepard became the first American in space; shortly after that, President John F. Kennedy challenged the U.S. to commit itself to landing a man on the moon. And in 1962, another group of nine astronauts joined the “Original Seven.”

In June 1963, the Navy’s Special Projects Office, Washington, D.C., informed Cernan they wanted to recommend him to NASA for further evaluation. Cernan was one of 400 astronaut candidates interviewed in Houston, where the Manned Spaceflight Center would be built the following year. NASA selected Lt. Cernan and 13 others out of that group that October.

Gene, his wife Barbara and 10-month-old Tracy Cernan moved to Houston in January 1964, following his private graduation ceremony. After the Mercury flights, two unmanned and 10 manned Gemini flights were planned, followed by Apollo. Cernan was assigned to work at Mission Control during the Gemini 1, 2, 3 and 4 flights; his task was to monitor the propulsion systems.

In November 1965, Cernan was told he’d be on the backup crew for Gemini 9, with Tom Stafford (at the time working on Gemini 6) serving as backup commander. The main crew was Elliot See, in command, and Charlie Bassett.

Gemini 9, a three-day mission, was to fly into orbit in May 1966, join up with an Agena rocket, light off the Agena engine to push into deeper space, and perform several complicated rendezvous procedures. Bassett was to do a spacewalk, wearing the complicated astronaut maneuvering unit for extra-vehicular activity, connected to the spacecraft by only a long, thin tether.

When See and Bassett perished in a T-38 crash in February 1966, Stafford and Cernan, recently promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander (at the age of 31) would take their places as the prime crew of Gemini 9. Cernan would fly the AMU.

On May 17, 1966, the Atlas-Agena lifted off smoothly from the Cape, but the Agena separated late and plunged into the Atlantic, as Cernan and Stafford waited at Pad 19 in their tiny Gemini spacecraft, perched on the nose of the Titan II. The launch was scrubbed.

Instead of an Agena target vehicle, they would now use an alternate docking target, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation’s Augmented Target Docking Adapter, called the “Blob.” After another scrubbed launch on June 1, on June 3, the Atlas blasted away from the Cape, the ATDA separated to lock into an almost circular orbit, and Cernan and Stafford were on their way, spotting the ATDA on their orbit.

When they parked about three feet away, they discovered it was tumbling out of control. The fiberglass conical nose shroud that should’ve fallen away from its docking collar once in orbit was still in place. Since docking was impossible, it was decided instead to add two more rendezvous maneuvers to the flight plan.

On the third day, Cernan strapped on his chest pack and readied for EVA. Following a 12-minute spacewalk by Alexei Leonov and a 21-minute walk by Ed White, the third man to walk in space was to take a two-and-a-half-hour walk. Outside the craft, with nothing to stabilize his movements, Cernan continuously tumbled out of control as he fought with his wayward umbilical cord. After making his way awkwardly to the rear of the spacecraft in his bulky, inflexible spacesuit, he struggled into the AMU. As he was hauled through space, he worked through the 35 different functions required to fly, eventually flipping the final switch to power up the backpack.

An hour and 37 minutes into his spacewalk, while struggling for leverage, and fighting to see through a fogged visor, he finally strapped himself into the small seat. But when Stafford reported that the workload was four or five times more than what had been anticipated, that communications had degraded, and that Cernan—whose heartbeat had almost tripled—wasn’t able to see through his visor, Cernan was first told to rest, and eventually, that he wasn’t to proceed with the AMU.

The disappointed and exhausted astronaut now had the tasks of getting out of the backpack and back into the spacecraft. With the backpack finally removed, the six-foot astronaut scrunched down and groped blindly until he was able to wrap his gloves around the hatch, lift it open and stick his feet inside. Inching lower into the spacecraft, he forced his legs into a duck-walk position. Excruciating pain shot through his legs as he pulled his body lower, twisting and managing to slide his heels over the edge of the seat while pushing his knees beneath the instrument panel.

Halfway in the spacecraft, his boots were now planted firmly against a steel plate that sealed the front side of the seat, toes pointed down; his legs were bent in a V position as he pressed down even further on them. After managing to force his shoulders below the level of the hatch, Cernan bent his neck and head, and pulled on the hatch, but it hit the top of his helmet and wouldn’t close. Stafford was able to lower the hatch further, and jam it down another few inches, catching it on the first tooth of a closing ratchet. Finally, the hatch closed enough so that it couldn’t pop open.

Cernan couldn’t unfold his feet, which were still tight beneath him, nor could he push his torso any lower, since his knees were pressed hard against the underside of the panel. The hatch was finally locked tight, but he was in excruciating pain.

“If we can’t pressurize the spacecraft in a hurry and I have to stay this way for the rest of the flight, I’ll die!” he said.

With Cernan nearing unconsciousness, Stafford quickly pressurized the spacecraft. As the unyielding suit began to soften, Cernan painfully unfolded his feet, slowly straightened his body, and was finally able to fit back into his seat.

Cernan had spent two hours and nine minutes in space, “walking” about 36,000 miles, and making about one and one-third circles around the world. Still, he was disappointed. He felt he had been sent out to do a job and didn’t get it done. He wondered if it would be a determining factor if he made other flights.

On Monday morning, the astronauts returned to Earth, to a targeted landing zone about 350 miles east of Cape Kennedy. They had spent three days and 21 minutes in space, had flown 1,200,000 miles in 45 orbits and landed back on Earth with the most accurate landing in the U.S. space program’s history.

After maneuvering alongside the spacecraft, the “USS Wasp” lifted the Gemini 9 safely to the deck. Cernan and Stafford crossed the red carpet as cameras flashed and thousands of sailors cheered, and then took a congratulatory call from President Lyndon Johnson.

Even though Cernan remained disappointed regarding his spacewalk, it was tradition that an astronaut was bumped up in rank upon completing his first mission, and he found some solace in his promotion to commander. That put him about six years ahead of the normal pace of promotions.

At Cape Kennedy, Deke Slayton would lead four days of debriefing. That was followed by another week of questions in Houston by Capt. Al Shepard. Cernan began to feel a little better about his mission when Bob Gilruth, the director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, and others, determined Gemini 9 had been extremely successful, largely due to their rendezvous work.

Weeks later, thinking he knew the answer already, Cernan asked Stafford to let him in on why Stafford and Slayton had a hushed conversation before their launch, which had made Cernan uncomfortable. The men were due at their trailer to get into their suits, when Slayton had ushered Stafford into another room.

“Deke would brief us together on the weather and the recovery forces and all those other things, but it was unusual to take him into another room,” Cernan said.

When Cernan asked him, Stafford admitted that they were discussing what would happen in case of an emergency.

“EVA was a dangerous thing to do,” Cernan said. “Deke recognized the fact that it was a perilous situation. The AMU was something that NASA agreed to do for the Air Force, but wasn’t too happy about it. Deke told Tom, ‘If something happens to Geno out there, you’ve got to make a decision to come back by yourself.’

“I’m sure when I had all my problems out there that Deke was thinking about those kinds of things. But when I talked to Tom, God bless his soul, he said, ‘Geno, I never would’ve left you out there. I would’ve found some way to get you in.'”

In years to come, when they were able to laugh at the situation, Stafford had a different answer.

“If Geno had a problem out there, there’s no way I’d get him in the spacecraft,” Stafford once said in an interview. “He’d be dangling from an umbilical. He’d burn up on the way in, anyway. I’d have to cut him lose.”

Cernan said he didn’t like the idea of becoming “Satellite Cernan,” but had recognized long before then that a risk existed.

“In those days, we did things that had to be done,” Cernan said. “We thought we knew what the risks were. We tried to manage the risk, and then we decided to go forward, because if we didn’t, we’d never get there from here.”

At the end of June, Gene, Barbara and Tracy Cernan returned to Chicago for a celebration in his honor, including congratulations by Mayor Richard J. Daley and a parade attended by 200,000 people. Stafford returned to Weatherford, Okla., to be honored by his hometown.

Gemini 10 through 12

When Cernan received his next assignment, it was a rotation to the backup crew on Gemini 12. Cernan and Gordon Cooper, command pilot, would be backing up Jim Lovell, command pilot, and Buzz Aldrin.

Gemini 10 lifted off on July 18, 1966, for a three-day flight, carrying John Young, command pilot, and Michael Collins. Its primary purpose was to conduct rendezvous and docking tests with the Agena target vehicle. The mission plan included a rendezvous with the Gemini 8 Agena target and two EVAs. Collins logged two spacewalks, one at 49 minutes and one at 39 minutes. Both EVAs were cut short due to difficulties.

Gemini 11 launched less than two months later, on Sept. 12, 1966. Charles “Pete” Conrad, command pilot, and Dick Gordon had the primary objective of rendezvousing and docking with a Gemini Agena target vehicle; secondary objectives included practice docking and performing an EVA. Gordon logged two spacewalks, one at 33 minutes and another lasting two hours, eight minutes. During EVA, he tethered the two spacecraft together with a 30-meter line. Even with the AMU, Gordon also had a rugged EVA.

Knowing Collins and Gordon also had difficulties, Cernan began to feel even better about his spacewalk.

“As it turned out, Gemini 10 and 11 proved that the problem was preparation,” he said. “It was what we were trying to do in zero gravity; we didn’t understand. Looking back at Gemini 9, it’s like an Apollo 13. It wasn’t a failure; it was a success, because of what we learned.”

After Cernan likened spacewalking to swimming in zero gravity, it was decided to start training in a water tank.

L to R: Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Thomas Stafford receive a warm welcome as they arrive aboard the prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier “USS Wasp.”

“We did a lot of things that we probably wouldn’t have done if those problems hadn’t shown up in Gemini 9,” he said. “There was a lot that we didn’t know about the spacesuit’s ability to support the amount of work we could do. Even though we were in a zero-G environment, not walking on the moon, we tried to extrapolate to what it would be like to work outside the spacecraft. We found out that in the zero-gravity environment, we needed to learn a lot more—about the laws of motion and about giving ourselves some handholds and anchoring our feet and all kinds of different things.”

Cernan said that those three EVA missions led to various changes, including the installation of various handholds, railings and stirrups by NASA engineers on future spacecraft.

Launched on Nov. 11, 1966, and lasting nearly four days, Gemini 12 had the primary object of rendezvousing, docking and evaluating EVA. Although it was initially intended for Aldrin to wear the AMU, it was decided it was too risky.

“The mission was reassessed,” Cernan said. “We created all kinds of tasks to see whether we could work around the problems that we uncovered earlier.”

Aldrin performed those tasks while firmly anchored to the spacecraft. He posted a spacewalk record of five hours, 30 minutes, spread over three EVAs. Aldrin and Lovell returned to Earth on Nov 15, 1966.

The 10 manned flights of Gemini proved every major objective for a trip to the moon could be met.

“The Soviets had still not conducted a true rendezvous in space, had never docked two spacecraft, and had only 12 minutes experience with a single spacewalk,” Cernan said.

Losses for the U.S. and Russia

There would be three crewmen on each manned Apollo flight. Eventually, for Apollo 1, Deke Slayton chose Gus Grissom, commander, Ed White, command module pilot, and one of Cernan’s closest friends, Lt. Cdr. Roger Chaffee, lunar module pilot, to ride into space aboard a Saturn 1-B rocket. The mission required the command module pilot to remain in orbit around the moon while the mission commander and lunar module pilot descended to the surface.

After waiting expectantly for his assignment, Cernan was placed on the backup crew of Apollo 2, as lunar module pilot, with Stafford, commander, and John Young, command module pilot. The prime crew was initially Wally Schirra, commander, Donn Eisele, command module pilot, and Walt Cunningham, lunar module pilot.

“That flight was going to be an Earth-orbit flight, and repeat Gus’ flight,” Cernan said. “Wally didn’t like that at all. He finally talked people into canceling out his flight.”

When Apollo 2 was scrubbed, Schirra’s crew became the backup crew for Apollo 1. Cernan, Stafford and Young became another backup crew for that mission.

The launch date of Apollo 1 was to be Feb. 21, 1967. But on Jan. 27, 1967, the U.S. space program came to a standstill when a fire on the pad took the lives of the Apollo 1 prime crew. On that day, Grissom, White and Chaffee were conducting tests in a spacecraft perched atop a Saturn 1-B rocket at Cape Kennedy. Since they were conducting a “plugs out” test, everything was being run as it would be for a real mission, except the Saturn wasn’t fueled.

Eventually, it would be determined that a spark ignited somewhere in the wiring and the pure oxygen environment within the spacecraft created a holocaust.

“The guys fought for their lives, trying to open the heavy hatch, but died in a matter of seconds, asphyxiated in their suits,” Cernan said.

When the accident occurred, Cernan, Stafford and Young were at the North American Aviation plant in Downey, Calif., in a duplicate spacecraft.

“We were doing a support test of what they were doing at the Cape,” Cernan recalled. “We were doing an altitude chamber test on a pair of spacecraft—Block I models. Block I was capable of orbiting the Earth. Down the line, the Block II would be capable of going to the moon.”

Two months later, on April 23, 1967, Russia would also suffer a loss that would bring their space program to a halt. Cosmonaut Vladimir M. Komarov perished when the Soyuz 1 malfunctioned after a vital solar panel needed to provide electricity to the spacecraft refused to unfold, and electrical circuits failed. He eventually punched through the reentry phase, but his parachutes failed, and he crashed to his death in the Orsk region of Russia.

Regrouping

In the U.S., as an investigation into the Apollo 1 accident continued, which would eventually identify 10 possible causes of the disaster—all electrical failures—changes were being discussed.

“As a result of that accident, we completely redesigned the Apollo command module spacecraft,” Cernan said. “We effectively redesigned it into the Block II lunar-capable spacecraft—but even with more capability than the Block II spacecraft would’ve had.”

In April 1967, Slayton announced that the first manned Apollo mission, which would take place after a few more equipment tests, would be designated Apollo 7.

“At first we numbered only the manned flights,” Cernan explained.

Stafford, Young and Cernan would now be backing up Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham, in a completely redesigned spacecraft. They would also be the prime crew of Apollo 10; their backups would be Gordon Cooper, commander, Donn Eisele, command module pilot, and Ed Mitchell, LM module pilot.

On Oct. 11, 1968, 21 months after the Apollo 1 fire, Apollo 7 was launched on a Saturn 1-B rocket, from Cape Kennedy, Fla. The crew spent 11 days in space, fully testing the command and service module systems.

Cernan said that up until that flight, it was thought that Apollo 10 would be the first mission to go 250,000 miles, all the way to the moon, and then attempt to land.

“The Russians had been close to orbiting the moon, so we modified the original sequence,” he said.

On Sept. 14, 1968, as a precursor to manned spaceflight, the Zond 5 was launched from a Tyazheliy Sputnik. On Sept. 18, the spacecraft flew around the moon.

“We had ‘go fever.’ It was felt that we had to beat the Russians to the moon, even if we didn’t land,” Cernan said. “On Wally’s flight, the Apollo spaceship command module performed so well that we decided to go ahead and send Apollo 8 to the moon, but without a lunar module. It was behind schedule.”

On Nov. 10, 1968, the Zond 6 was launched on a lunar flyby mission from a parent satellite, carrying scientific probes, photography equipment, and a biological payload. The craft flew around the moon on Nov. 14.

On Dec. 21, 1968, Apollo 8 launched aboard a three-stage Saturn V. Frank Borman, the commander, Jim Lovell, the command module pilot, and Bill Anders, the LM pilot, took three days to travel to the moon, which they orbited for 20 hours. The crew celebrated with a Christmas broadcast.

The moon race was over. At the end of February 1969, the Soviets sent up the N-1, a huge rocket, for its first unmanned test launch. But after several malfunctions, the N-1 blew apart, firmly putting Moscow out of the game.

Apollo 9

Apollo 9, a 10-day Earth-orbital mission, launched on March 3, 1969, as the first manned flight of the Apollo lunar module. During the flight, commanded by Jim McDivitt, lunar module pilot Russell Schweickart performed a 37-minute EVA. David Scott was the command module pilot for the mission.

Although there had been a chance that it would touch down on the lunar surface, in late January it was announced that Apollo 10 would be a full-dress rehearsal instead. The biggest reason was that the lunar module they were to fly was still too heavy to land on the moon.

“We would have had to wait another two months for the one that Neil flew to be completed,” Cernan said. “The question was, ‘If we send 10 all the way to the moon with the lunar module, put them in harm’s way, do we go ahead and attempt a lunar landing? Or do we go and do everything but the lunar landing, just to check out the capability of going around the moon, and how the lunar module is going to perform, and fire all the lunar module’s engines around the moon, do everything but the last 50,000 feet?’ Then Neil and his crew could repeat everything we did, but then continue on and make a landing. That’s the way it all worked out.”

There would still be risk.

“We were only the second crew ever to go to the moon,” Cernan said. “We were going to get out of the only spacecraft that could get us home, and get into a lunar module.”

It was only the second flight of the LM.

“We couldn’t get home in a lunar module,” he said. “So once we separated, we had to be able to not only check the lunar module out, but also we had to be able to get back to the command module to be able to rendezvous. No one had ever rendezvoused around the moon.”

On May 18, 1969, aboard a Saturn V, Apollo 10 launched on schedule, at 12:49 p.m., EDT. The eight-day mission began with a violent liftoff due to a severe pogo motion. After being given the go for the burn that would get them to the moon, finally, they started the countdown for the translunar injection that would push them out of Earth’s orbit.

The last major chore of the first day was to turn the command module, “Charlie Brown,” around, to dock with the LM, “Snoopy.” On the third day, after they had outrun the Earth’s gravitational pull, the moon’s gravity caught and dragged them forward. They were now a quarter-million miles from home, and within 60 miles of the moon.

An engine burn done during their first pass behind the moon put them into lunar orbit. After they were locked into orbit, the astronauts got a close look at the moon below them. But what was most impressive to Cernan was their first Earthrise, which he described as “overpoweringly beautiful.”

After two low passes over their landing site, Cernan and Stafford started down to the moon in Snoopy with the descent engine firing.

“We started the trajectory, checked the landing radar, and took lots of photographs,” Cernan said. “We did everything they would do on Apollo 11, except we left 47,000 feet between us and the surface.”

After looping Snoopy around the moon once more, to the highest point of their orbit on the far side, they made a steep run back to pericynthion (the point nearest to the moon in their orbit), before preparing to simulate a launch from just about where Apollo 11 would have to blast off from the surface.

Since their mission was to try everything that Apollo 11 might have to do, they also simulated an emergency, which turned into a real one.

“We misplaced a switch on a computer,” Cernan said.

Cernan had switched navigation control from the Primary Navigation Guidance System computer (which when tuned to the positions of distant stars, provided an exact navigational reading) to the Abort Guidance System, an auxiliary navigational system for use nearer to or on the moon.

“The Abort Guidance System was just an abort computer; it had minimum capability,” he said. “We were going to test it and see whether it was going to work okay, to get these guys off the surface.”

A moment later, not knowing Cernan had already hit the switch, Stafford hit it, putting it back to where it had been before. Then, they prepared to fire the ascent engine.

“When we staged the vehicles, they started flip-flopping through the sky,” he said.

“In about 15 seconds, I saw the lunar horizon go past about eight times in different directions. We didn’t know it at the time, but I guess it wouldn’t have been but a few more seconds that we would’ve taken enough energy out of our orbit to come back down to the moon, in a not very pleasant manner.”

Finally, nearing a disastrous gimbal lock, Stafford overrode the computers and took manual control of the spacecraft. As quickly as it had started, the 15-second episode ended.

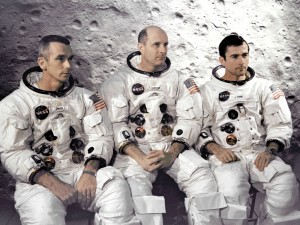

The prime crew of the Apollo 10 lunar orbit mission at the Kennedy Space Center, from L to R: Eugene Cernan, LM pilot; Thomas Stafford, commander; and John Young, command module pilot.

After resetting everything, they fired the ascent engine, on schedule. Five and a half hours later, Snoopy trailed Charlie Brown by only 40 miles. Behind the moon, Young completed the linkup. As they slid behind the moon again, they jettisoned Snoopy to eternally orbit the sun.

After nine hours of sleep, they spent their thirty-first and final revolution around the moon going through the checklist for their transearth injection, a maneuver that had been done only once before. The rocket engine fired exactly when it was supposed to, and Charlie Brown shot out of lunar orbit. With a perfect TEI, they began the long 55-hour trip back to Earth.

They landed gently on a nearly calm sea about 400 miles east of Pago Pago in American Samoa. Apollo 10 had flown for eight days, three minutes and 23 seconds. Apollo 10 was the first to carry a color television camera; they made 19 broadcasts during the eight-day flight, for which they won a television Emmy award.

Over the years, many people have asked Cernan how it felt to be right there, and not be able to land.

“We would have liked to,” he said. “Sure, we would have enjoyed being given a shot at it. But in retrospect, the way things turned out, it was obviously the right decision to make. We stuck our neck out as far as we could, without actually landing.”

During their four-hour stay aboard the “USS Princeton,” the astronauts took a congratulatory call from President Nixon, before flying to Pago Pago, where about 5,000 flag-waving fans met them. When they landed at Ellington AFB on Tuesday morning, Slayton and several astronauts met them as a military band played “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” Hundreds of civilians had gathered at the fences.

When Cernan reunited with his family, he proudly told Tracy that her father had flown close to the moon.

“You know, it’s real far away in the sky, up where God lives,” he said. “Daddy’s gone closer to the moon than anyone ever has before.”

“Daddy, now that you’ve gone to the moon, when are you going to take me camping, like you promised?” was the unexpected response.

It was a moment of clarity for the astronaut.

“I really impressed her,” he said. “I thought it was show and tell and I was the hero on the block, for at least a week. You know, when your daughter goes to school with the likes of Alan Bean’s daughter and Neil’s kids and Buzz’s kids, and Mike Collins lives two doors away, going to the moon just ain’t a big deal for a six-year-old. That brings you down to Earth in a hurry.”

There was another thing that brought Cernan back to Earth. When they were having problems, he didn’t realize that, as Barbara Cernan put it, his language had been a “little salty.”

“When we put the computer switch in the wrong place, we were in Vox, where the keys were open,” he recalled. “We were talking, because it was a hair-raising time. All of a sudden, I said, ‘Son-of-a-bitch! What the hell happened?’ The whole world heard me. I had no idea I said that until I got home.

“When we got home we had 50 letters saying things like, ‘Congratulations. You made us proud. Apollo 10 was a great flight. You’re great Americans. You guys put your pants on one leg at a time. I would have said much worse!'” he recalled. “Then, the fifty-first letter would say, ‘Oh, you made us proud. It was a great flight, but how can you use such language in front of my kids?'”

Cernan was asked to apologize to the whole world.

“But I did it in my own way,” he said. “I said, ‘For those who understood, I thank you. For those who I offended, I’m sorry.’ There was some preacher down in Miami who wanted me thrown out of the space program.”

But Cernan remained in the program, and that incident was soon forgotten.

Onward

Ten more missions were scheduled after their return. Some time after getting back from Apollo 10, Cernan took a gamble. He turned down a “potential” opportunity to walk on the moon, by telling Slayton he wanted his own command.

“Deke was starting to assign a crew for Apollo 11 and 12, and they were looking to assign other crews down the line,” he recalled. “Tom Stafford wasn’t going to fly an Apollo anymore; he made that decision.”

Stafford was headed either to a new position within the program or a run for the U.S. Senate from Oklahoma.

“John Young and I were up for rotating from 10 to the backup crew of 13,” Cernan said. Young would be in command of the Apollo 13 backup crew, with Cernan again taking the role of LM pilot.

“Again, nothing was guaranteed, but if you looked ahead, chances were the Apollo 13 backup crew would have rotated to Apollo 16 prime crew,” he said. “As a matter of fact, John did exactly that.”

But Cernan told Slayton that he wanted more than that.

“He never guaranteed what might be an opportunity to land on the moon on Apollo 16,” Cernan said. “I told him, “I want a chance to command my own crew.’ He thought I was crazy.”

There was no guarantee that he would get a backup commander slot, either, which would have rotated to another flight.

“Turning down that opportunity was one of the biggest risks I ever took in the space program,” he said.

Once Cernan turned down the assignment as backup crew of Apollo 13, Slayton assigned Charlie Duke in his place.

“Subsequent to that, Apollo 14 was assigned,” Cernan said. “That was Shepard and his guys (Stuart Roosa, CM pilot, and Ed Mitchell, LM pilot). Shortly thereafter, they assigned a backup crew. Deke gave me a shot at being backup commander of 14. Ron Evans and Joe Engle were assigned with me. Looking down the line, the backup crew would possibly rotate to flying Apollo 17.”

A lot of things happened along the way that could have changed that. The historic flight of Apollo 11 launched on July 16, 1969. Commander Neil Armstrong and LM pilot Buzz Aldrin landed in Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), on July 20, while Michael Collins, making the flight after months of rehabilitation following neck surgery, continued in lunar orbit.

After making that “giant leap for mankind,” Armstrong and Aldrin set up scientific experiments, took photographs, and collected lunar samples. The LM took off from the moon on July 21 and the astronauts returned to Earth on July 24.

With that first step on the moon’s surface accomplished, Apollo 12 launched on Nov. 14, 1969. On Nov. 19, command module pilot Dick Gordon continued in orbit, while Pete Conrad, commander, and LM pilot Alan Bean landed in Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) in the LM. Besides setting up scientific experiments and taking photographs, the astronauts examined the nearby Surveyor 3 spacecraft that had landed on the moon two and a half years earlier and removed pieces for later examination on Earth. They collected lunar samples on two moonwalk EVAs. The LM took off from the moon on November 20; the astronauts returned to Earth four days later.

A close call

When Shepard was grounded due to an inner ear disorder in 1963, he lost out on the chance to fly Gemini 3. That same year, he had become chief of the Astronaut Office. Shepard was restored to full flight status in May 1969, following corrective surgery.

Initially, Slayton decided to give him the command of Apollo 13, but then persuaded him to slip back one mission to gain extra training time. Instead, Jim Lovell, scheduled to command the prime crew of Apollo 14, moved up one flight, with his crew of Ken Mattingly, CM pilot, and Fred Haise, LM pilot. The Apollo 13 backup crew was John Young, commander, John “Jack” Swigert, command module pilot, and Charlie Duke, LM pilot.

Two days before the launch of Apollo 13, Ken Mattingly was removed from the prime crew because he had been exposed to German measles. His backup, Swigert, replaced him.

Apollo 13 launched on April 11, 1970. The mission was aborted after nearly 56 hours of flight due to the loss of service module cryogenic oxygen and consequent loss of capability to generate electricity or to provide oxygen or water. When breathable oxygen began to run out in Apollo 13’s command module, which was the crew’s living quarters, the three astronauts were forced to seek shelter in the small lunar module.

“Joe Engle and I were training, since we were backing up Apollo 14,” Cernan said. “He was the lunar module pilot. We were probably the most familiar, at that point in time, with the lunar module. We were in the lunar module simulator for a couple days trying to figure out some kind of techniques to get them back.”

A faulty heater had shorted out, detonating one of the oxygen tanks, and blowing out a side of the service module that contained the crew’s life-support systems. It was later learned that the number two oxygen tank that exploded was one that had been replaced on the Apollo 10 spacecraft previous to their flight, and later refurbished.

Finally, when time was up, Mission Control radioed up the best procedures that had been devised. The crew returned safely to Earth on April 17, 1970. Years later, Lovell wrote a book about his flight, which was later made into the dramatic motion picture, “Apollo 13.”

Cernan said that after that near disaster, the fear of losing a crew of astronauts in space replaced the daring that started the program in the first place.

“The brush with disaster took much of the backbone right out of some of NASA’s leaders,” he said.

Less than two months after Lovell’s crew came home, the final scheduled mission of the moon exploration series, Apollo 20, was cancelled.

Apollo 14

As Cernan trained as Shepard’s backup for Apollo 14, he received the good news that he had been selected for promotion to the rank of captain. At 36, that made him the youngest captain in the Navy; he had reached that rank after just 14 years of service.

In 1970, serious politicking began in Houston, Washington, D.C., and at Cape Kennedy over who should fly Apollo 17. Two crews were being considered. They were Cernan, Joe Engle, who flew the X-15 into the fringes of space 16 times, and Cernan’s good friend, Ron Evans, a veteran of 100 combat missions in Vietnam. The other crew under consideration was the backup crew of Apollo 15, which included the crew’s commander, Dick Gordon, Vance Brand and Dr. Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, one of the program’s acknowledged experts in geology.

“There was a lot of lobbying to get a scientist on at least one Apollo flight,” Cernan said.

Cernan tried not to think about it while he concentrated on doing the best job he could backing up Shepard.

“On any backup crew, you have a real responsibility to make sure that every base is covered so that the prime crew doesn’t have any problems when they’re flying,” he said.

Once he’d gotten to know Shepard, he’d been surprised. He’d expected the man to be cold and domineering; after all, his nicknames were “Ice Man” and “Ice Commander.” In fact, because of what he’d observed about him, when he was first given that assignment as backup commander, he assumed Slayton was testing him.

“In the early days, when I first got in the program, I was afraid to say hello to Al,” he recalled. “In the program, out of the program—it didn’t make any difference—he never let anyone get very close to him. People used to say, ‘This guy’s really aloof.’ It was just his nature; he didn’t just allow people to get close to him. I thought maybe Deke was thinking, ‘If he can back up Alan Shepard, he can back up anybody.’ He was a tough guy, and he was good. I thought it was going to be a real challenge.”

Cernan said that his happiness in being able to fly again transformed Shepard. Cernan believes it also helped their relationship when he walked into Shepard’s office, congratulated him on his command, told him how proud he was to be on his backup crew and that they’d support him, and then told him “his credentials.”

At first, Shepard just frowned.

“Then I got to the point where I said, ‘Alan, if you have a problem, I want you to know I’ll be ready to take your place and get the job done.’ I wasn’t sure he liked that,” Cernan said.” And then, I said, ‘As a matter of fact, when the time comes, if I have to, I’ll be able to do the job better than you can.’ I don’t know what possessed me to say that. I thought, ‘This is just going to be one of those hellish relationships for the next year or so, working on this flight.’ But, as it turned out, he got a big grin on his face and stuck out his hand and said, ‘Geno, we’re going to have a great time.'”

Cernan said that since so few people really got to know who Alan Shepard really was, the relationship that developed between them was even more special.

“It wasn’t just a working relationship,” he said. “It was a real personal relationship. We just got to be very close on that mission.”

By January 1971, Shepard, his CM pilot, Stu Roosa, and the LM pilot, Ed Mitchell, were prepared for their mission, as was their backup crew. But a week before Shepard’s flight, something happened that made Cernan think his chances had narrowed for commanding Apollo 17.

On Saturday, Jan. 23, 1971, while practicing lunar landings at the Cape with the small H-13 Bell helicopter ( the closest flying approximation to a moon lander they had without using the rocket-propelled Lunar Landing Training Vehicle simulator at Ellington, back in Texas), Cernan crashed. He had done a nose over, swooping down from a couple of hundred feet to dance the chopper around the island beaches, and the toe of his left skid had dug into the Indian River.

When he crashed, what remained of the demolished chopper, with him strapped inside, began to sink. Cernan freed himself from the helicopter and swam for the surface, as a wall of flames closed around him. A woman in a small fishing boat eventually wrestled him out of the water, and he was rushed to Patrick Air Force Base for initial treatment for his injuries and burns.

“I about killed myself,” he said. “It was one of those pilot-induced accidents. It was a dumb thing. I flew into the water, and I thought, ‘God, I’ve really ripped my knickers now, as far as getting a chance to command Apollo 17.’ Nobody who is given the responsibility of command of a mission to the moon is going to do something as dumb as fly into the water; that’s the way I looked at it.”

He knew Slayton would have to tell the press, the NASA brass, and the American public what happened. Slayton tried to offer Cernan an easy way out, which was to say that the engine quit on him. But Cernan couldn’t do it.

“I told it like it was,” Cernan said. “Probably, in retrospect, it was the best thing I could do.”

Cernan was back on flying status within two days. The incident caused few ripples; Apollo 14 was still the center of focus at the Cape, and Cernan’s accident quickly became old news. Shepard, however, couldn’t resist one comment, after listening to his friend tell him to watch his step so many times.

“After we got to be friends, I always told him, ‘Don’t stumble, because I’m right behind you,'” Cernan grinned. “After I crashed, he said something like, ‘Oh, Cernan, you finally gave up. You’re finally going to let me fly this mission.'”

On Jan. 30, 1971, hours before the launch of Apollo 14, Shepard asked his backup commander to go with him to look at “their” Saturn V spacecraft. It was a proud moment for both of them.

“He and I went out and stood below his booster,” Cernan said. “I really learned something about commitment from him. All that time, he could have given up and gone another direction, but he stayed with it, and he finally got himself a flight. He was finally going to do what he wanted to do; he was going to go to the moon. He was a great aviator, and he was so dedicated and passionate about it.”

Apollo 14 launched on Jan. 31, 1971, landed on the moon on Feb. 5, and returned home on Feb. 9. The backup crew had their fun, in the meantime.

“Everybody pulled a lot of ‘gotchas’ on each other,” Cernan said. “Once we broke the ice with Al, that became part of the flight. We used to call Al the old man, Ed Mitchell was the fat man, and Stu Roosa was the cute little redhead. We were the backup crew, but we called them ‘The Three Rookies,’ because none of them had ever flown; well, Alan had flown, but he had only 16 minutes. We always called ourselves ‘The First Team.'”

Part of their fun was making an Apollo 14 backup crew patch.

“The astronaut emblem is a star, with rays emanating out of the star, leaving an orbit around the Earth and headed towards the moon,” Cernan explained. “For Apollo 14, the patch has their names on it. We made an exact replica of that patch, but instead of the astronaut emblem coming out, we had the wolf from the ‘Road Runner.’

“The wolf was headed towards the moon. On the moon, we put a roadrunner out there, and we put a banner around his neck. We had a scarf around the roadrunner’s neck that said, ‘The First Team.’ He was holding on to an American flag, planted in the moon. The implications of all that were, ‘The First Team beat you to the moon.’ On the top, instead of Apollo 14, we put, ‘Beep! Beep!’ Around the bottom, we put our names. It’s the only backup patch in the history of the space program.”

The backup crew hid several of the patches throughout the spacecraft before they launched.

“We hid them in lockers and everywhere,” Cernan said. “So, on the way to the moon, on the moon, and on the way back, whenever they would open up a little door to get something, one of these patches would float out. On the intercom, Shepard said, ‘Tell Cernan, ‘Beep, beep, your ass!'”

More cancellations

Apollo 15 launched on July 26, 1971, with David Scott as commander, Al Worden as CM pilot and Jim Irvin as LM pilot. They landed on the moon on July 30; using a lunar roving vehicle for the first time, Scott and Irwin explored the geology of the Hadley Rille/Apennine region. They returned to Earth on Aug. 7, after EVA duration of 18 hours, 35 minutes.

In September, Apollo 18 and 19 were cancelled. At that time, the crew of Apollo 17 was still undecided. Cernan thought his relationship with Shepard was a boon, and that Stafford’s recent placement as head of the Astronaut Office definitely helped him. But Jim McDivitt, the new chief of the Apollo program section, was a strong fan of Dick Gordon, as was Gordon’s old friend and flying partner, Pete Conrad.

“There were a lot of guys in my camp and a lot of guys in Dick Gordon’s camp,” Cernan said.

His crash seemed to be behind him, but Gordon still had Jack Schmitt, the scientist, which could possibly be his trump card. Finally, Slayton was ready to reveal the Apollo 17 crew selection. Would it be, Gene Cernan, Ron Evans and Joe Engle, or Dick Gordon, Vance Brand and Jack “Dr. Rock” Schmitt?

Tune in next month to find out the answer, and for the conclusion of “The Last Man on The Moon.”

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part I

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part III Finale