By Di Freeze

The prime crew for Apollo 17: Eugene A. Cernan, commander (seated in the lunar roving vehicle trainer); command module pilot Ronald E. Evans (standing on right); and lunar module pilot, Harrison H. Schmitt. The Apollo 17 Saturn V is in the background, and

In 1970, as Captain Eugene A. Cernan trained as backup commander to Mercury astronaut Captain Alan Shepard for Apollo 14, serious politicking continued over who should fly Apollo 17, as well as lobbying to get a scientist on at least one Apollo flight. One crew being considered was Cernan, Joe Engle and Vietnam veteran Ron Evans. The other was the Apollo 15 backup crew of Dick Gordon, Vance Brand and Dr. Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, one of the program’s acknowledged experts in geology.

Before the question of which crew would go was answered, Apollo 20, the final scheduled mission of the moon exploration series, was cancelled. It was feared the same thing could happen to Apollo 18 and 19. That fear came true following the successful flights of Apollo 14 and 15; 18 and 19 were cancelled in September 1971.

As things stood, there was even a question if there would be an Apollo 17. Even if there wasn’t, Cernan could comfort himself with the fact that he’d accomplished quite a bit, especially for a 36 year old.

A graduate of Purdue and the Navy Post Graduate School, Cernan had been selected in 1963 among the third group of astronauts chosen, known as “the 14.” His first space flight was in June 1966. During Gemini 9, Lt. Cdr. Cernan spent two hours and nine minutes in space during extravehicular activity. He and Tom Stafford spent three days and 21 minutes in space, flying 1,200,000 miles in 45 orbits.

Cernan’s next flight was Apollo 10, in May 1969. As lunar module pilot, Cernan made that flight with Stafford, commander, and John Young, command module pilot, who had each flown in space twice. The second crew ever to go to the moon, a quarter-million miles from Earth, Cernan and Stafford did everything the Apollo 11 crew would later do, except they left 47,000 feet between them and the moon’s surface. The duration of the flight was eight days, three minutes and 23 seconds.

After getting back from Apollo 10, Cernan had taken a gamble. He turned down the assignment as backup crew of Apollo 13, knowing that from there, he would probably rotate to Apollo 16, giving him a “potential” opportunity to walk on the moon. He took that risk because he hoped he would get a chance to command his own crew, instead of again taking the role of lunar module pilot.

As a result, he had been given the assignment as backup commander to Shepard for Apollo 14. But, with the cancellation of Apollo 18, 19 and 20, he now awaited his fate. In October 1971, Slayton sent his recommendation to Washington, D.C., requesting Cernan, Evans and Engle as the Apollo 17 crew. But word came back that whoever else flew, Schmitt would have to be one of the crew.

“Deke had to decide whether he was going to rotate the whole Apollo 15 backup crew, or split it up, to give the flight to Ron and me, and then insert Jack Schmitt on our crew,” Cernan said. “Fortunately for me and Ron, he split it up. I think Alan had a big influence on that selection.”

Although he was happy to have the assignment, Cernan deeply regretted that Engle wouldn’t be flying with them.

“But Joe did end up commanding the second space shuttle mission,” he said.

With Cernan in command, Evans would serve as the command module pilot and “Dr. Rock” as the lunar module pilot. Their backups would be John Young, Stu Roosa and Charlie Duke. Both Duke and Young were on the prime crew of Apollo 16, which launched on April 16, 1972.

On April 21, Commander Young and Duke, the LM pilot, landed on the moon, as Tom Mattingly manned the command module. After conducting several scientific experiments, taking photographs and collecting lunar samples, they return to Earth on April 27.

Apollo 17

Apollo 17, the sixth and last Apollo mission in which humans would walk on the lunar surface, would be a 13-day flight. Cernan was determined to make sure it was successful, and although 17 would be the last Apollo flight, he wanted to boost morale and confidence regarding the future of the space program.

“Apollo Seventeen is not the end, but rather the beginning of a whole new era in the history of mankind,” he would say, at parties, in factories, or wherever a pep talk seemed needed.

Cernan said the space program received a lot of attention prior to Apollo 10, since the U.S. was still headed to the moon, but that the media got very blasé after Apollo 11.

“After Apollo 11, it was like, ‘We’ve been to the moon; where now, Columbus?'” Cernan recalled. “They were blasé during the early stages of Apollo 13, until they had that major problem.”

He said the lunar rover added some excitement to 15 and 16. Apollo 17 had several elements that recaptured attention, including the fact that it was the last Apollo flight and they would be on the moon for three days. Also, the launch was scheduled for a few hours after sundown.

“In order to get to where you want to land in December, and get the sun behind you at the proper angle when you land, it required us to launch at night,” Cernan said. “There had never been a manned flight launching at night, so we started out with a big bang. That night launch was one of the more phenomenal things people remember about Apollo 17. I heard all kinds of descriptions of what it was like, such as ‘It was like a thousand suns.’ They could see it from Miami to Atlanta, up and down the coast.”

By sundown on Dec. 6, 1972, about 700,000 people had gathered to witness the historic launch. More than 50 of Cernan’s personal friends were there by invitation, including celebrities such as John Wayne, Connie Stevens, Bob Hope, Don Rickles, Dinah Shore, Johnny Carson, Henry Mancini and Eva Gabor.

Their launch window was between 9:53 p.m. and 1:31 a.m., Florida time. Due to computer problems, the Saturn V was finally able to launch on Dec. 7, at 12:33 a.m. After they began their 86-hour coast to the moon, Evans freed the command module from the third stage and linked America, with Challenger, the lunar module.

On Dec. 11, at 8:50 a.m., Houston time, Schmitt and Cernan climbed aboard Challenger. Many of the items they needed for the lunar landing were crammed inside the spacecraft; a folded lunar roving vehicle and other things too large to fit in the cabin lined the outer edges of Challenger.

They undocked at 11:21 a.m., and at 12:41 p.m., the two spacecraft spun around the backside of the moon in tandem. Evans, who would be operating two cameras and three multimillion-dollar instrument packages, took the command module back into a higher orbit while they headed the other direction, lowering their own position another eight miles.

Armstrong and LM pilot Buzz Aldrin had landed in the desert part of the moon. Cernan and Schmitt would land in the Valley of Taurus-Littrow, a deep, rugged valley surrounded by mountains on three sides, near the edge of the Sea of Serenity, at the northeastern edge of the moon. While on Earth, Cernan had named craters near where he planned to put Challenger down. His aiming points were Punk, named for his 9-year-old daughter Tracy; Barjean, for his wife, Barbara Jean; and Poppie, for his father, who had died a few years earlier.

Shortly after Challenger emerged from the far side, Houston confirmed everything looked good. Cernan fired the descent engine, and they began falling out of orbit. They were soon zooming toward the Valley of Taurus-Littrow.

After Cernan had spotted Poppie, Challenger swooped lower. As they made their 12-minute burn, which lowered them quickly toward the moon’s surface, Cernan was awed by the sight of the Earth, which “dangled like a colorful Christmas ornament smack-dab in the middle of Challenger’s window.”

They flew over the domelike Sculptured Hills (some more than a mile high) over which they had made their approach, before roaring into the eastern entrance of a lunar valley deeper than the Grand Canyon, surrounded by mountains. The North Massif rose to their right, South Massif to their left, and Family Mountain was about three miles away, at the far end of the valley.

After spotting Punk, as well as Frosty and Rudolph, which formed a small triangle of craters, and then Barjean, Cernan lowered the LM closer to the surface. After maneuvering over a house-sized boulder, he eventually spotted Camelot, a crater right in the middle of the dusty plain named after both the mythical kingdom and in memory of President Kennedy. He could also see Trident out the left window, and Lewis and Clark out the right. Camelot was as far as he could go, because it dominated a low plain they had dubbed Tortilla Flats, out of which jutted massive chunks of rock.

L to R: In this November 1971 photograph, Astronauts John Young, Eugene Cernan, Charles Duke, Fred Haise, Anthony England, Charles Fullerton, and Donald Peterson await deployment tests of the lunar roving vehicle qualification test unit.

When Challenger entered the Dead Man’s Zone, about 200 feet above the moon, Cernan searched between “automobile-size boulders” for a place to land. As he steadied the lander for the final hop, dust rose up and obscured the view. When one of the nine-foot-long wire sensors trailing from the pads of the lander legs brushed the surface, a light flashed on Cernan’s console and he shut down the rocket. Dropping the last few feet, they came to rest slightly tilted in a shallow depression—only 200 feet from the precise place picked as a target months earlier—at 1:54 p.m., four days, 14 hours, 22 minutes and 11 seconds after they had blasted off from Florida.

“Houston, the Challenger has landed!” Cernan joyfully reported.

Camelot

Four hours later, Cernan, wearing the backpack that contained his life-support system, cautiously descended Challenger’s ladder, and lowered his left foot, and then his right, to the moon’s surface.

“As I step off at the surface of Taurus-Littrow, I’d like to dedicate the first steps of Apollo Seventeen to all those who made it possible,” he called to Houston. “Oh, my golly. Unbelievable,” he said as he studied the vast emptiness around him, and noted the thick black sky, and the low sun, casting a long shadow beyond Challenger.

As he turned, trying to see everything, he was overwhelmed “by the silent, majestic solitude, the bland, stark beauty.” He was also amazed to see Punk, just an arm’s length away.

For the next three days, Cernan and Schmitt would set up scientific experiments, take photographs and collect lunar samples. First, they would need to learn to walk on this strange new surface. He said learning to walk in one-sixth gravity was like “balancing on a bowl of Jell-O.”

“There have been a number of people in zero gravity, but only 12 people have ever experienced one-sixth gravity,” Cernan said. “It’s a totally different world. I love one-sixth gravity. If I could turn Earth gravity into one-sixth gravity, I would!”

Eventually, he learned to shift his weight while doing a “sort of bunny hop.” Their first job was to unload the rover. They used lanyards, cables and hinges to lower it. After the “moon buggy” had been assembled, Cernan bounced into the driver’s seat. As he did, he couldn’t help thinking about Dr. Wernher von Braun, the former director of the Marshall Space Flight Center, and a conversation he’d had with von Braun when he was training to fly to the moon.

He had told Cernan that as “one of the explorers,” it was his turn to carry on the dream, and that he envied him. Cernan had been awed to hear that the brilliant visionary envied him, and realized that von Braun was living his dreams vicariously through their journeys into space.

“He was the ultimate engineer,” Cernan said. “But he was also a dreamer, just what the space program needed, far out in front of what was going on at the moment.”

Cernan had met von Braun shortly after he got into the space program. At a dinner, he found himself sitting at a table with about six or eight other “rookies” and von Braun.

“He said, ‘Don’t vorry about how you go to the moon. I get you there. You vorry about vat you do ven you get there. And you vill even drive a car on the moon,'” Cernan recalled.

Now he was preparing to do just that.

“Driving that car was really something,” Cernan recalled. “You hit a little pothole and you’ve got one wheel off the ground half the time. It really allowed us to go places that we never would have been able to get to if we had to walk. The valley we landed in was about 20 miles long and about five miles across. The mountains that surrounded it just towered above everything else. We were able to cover that whole valley with the lunar rover.”

Ed Fendell in Houston would remotely control a TV camera attached to the rover, so that the explorers could share their adventures with those back on Earth. In the meantime, Cernan, mesmerized by the spectacular sight of his home planet, tried to share “Earth” with his fellow explorer.

“Jack, you owe yourself 30 seconds to look up…at the Earth,” he pleaded.

“You seen one Earth, you’ve seen them all,” said the geologist.

Before leaving their “home base,” Cernan and Schmitt erected an American flag that had been carried to the moon and back by Apollo 11. Then, they moved on to position a sophisticated array of scientific instrumentation, at the heart of which was the Apollo Lunar Surface Exploration Package, which was powered by a small nuclear reactor.

When Cernan’s rock hammer, sticking out of his suit pocket, hit the rover while he was unloading gear, resulting in a section of the thin plastic fender cracking off, he used a strip of duct tape to hold it in place. They had four hours allotted for the deployment of the rover and the ALSEP, and 90 minutes set aside to journey south to the their first true geologic stop, the crater Emory. Not wanting to put that trip in jeopardy, they worked fast, but it was tougher than expected.

Wearing thick, rigid, multi-layered gloves, Cernan laboriously drilled into the rocky soil with a battery-powered drill to gather subsurface samples and plant heat-measuring devices, as Schmitt attempted to erect the gravity-wave detector, a delicate package designed to determine how the moon oscillates during an internal quake.

Eventually, Mission Control told them they were 40 minutes behind schedule, and that instead of the mile-and-a-half trip to Emory, they would stop halfway, in a boulder field near the crater Steno. After boarding the rover, they headed over a route pocked with craters of all sizes and strewn with large boulders. During their journey, directly into the sun, the broken fender fell off, and thick dust surrounded them.

They reached Steno, but were only able to make it partway up the crater’s rim. So, they turned around and drove slowly back to Camelot to amuse themselves with the ALSEP. After seven hours and 12 minutes on the surface of the moon, they headed back to Challenger, filthy and exhausted. Cernan said they now looked at the lunar module differently; it was no longer just their “ticket from space to the moon.”

“Now it was our home, our own little castle in Camelot,” he said. It was “the only sanctuary they had on the surface of this new world.”

After pressurizing the spacecraft, and stripping off his gloves, Cernan wasn’t surprised to discover the knuckles and backs of his hands were blistered. After helping each other wrestle their way out of the bulky suits, they strung their hammocks up and slept.

Eight hours later, on Dec. 12, at 12:48 a.m., Houston time, Mission Control woke them with Wagner’s volcanic “Ride of the Valkyries.” While they slept, John Young had come up with a way for Cernan to fix his fender bender; he would make a new fender, using geology maps folded into a rectangle, tape and screw clamps from the emergency lighting pack. By the time they headed across Tortilla Flats, for their second seven-hour trek, they were 84 minutes behind schedule.

After reaching their first destination, Hole in the Wall, at the foot of the South Massif, they spent an hour exploring boulders that had tumbled down the 8,500-foot mountain. Following several experiments, they drove toward the rim of a small crater a few hundred yards to the north, where they experimented further. At the end of the day, after traveling a dozen miles and visiting craters including Shorty, Lara and Camelot, their arms ached and their hands were raw and bleeding.

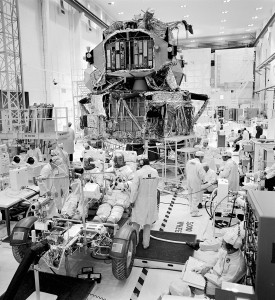

The Kennedy Space Center launch team continues the checkout of Apollo 17 flight hardware. A mission simulation to check out the lunar roving vehicle and all its systems was successfully carried out. Harrison H. Schmitt and Eugene A. Cernan.

The next morning, they struggled awake to the sound of “Light my Fire,” by the Doors. That day’s seven-hour adventure would include a round trip to the steep slopes of the North Massif, as well as a journey to the Sculptured Hills. Their first stop was a split boulder that had rolled down the mountain in a prehistoric avalanche, on which Schmitt performed a field study to piece together its volcanic history. The astronauts were exhausted, but Cernan gleefully made his way down the Sculptured Hills doing a kangaroo bounce, while Schmitt pretended to ski.

Back at Challenger, Schmitt cleaned up inside, while Cernan drove the rover about a mile away from the LM and parked it carefully so the television camera could photograph their takeoff the next day. As he dismounted, he knelt down and scratched Tracy’s initials, TDC, in the lunar dust.

Alone on the surface, he hopped and skipped back to Challenger. Throughout his stay, he had pondered what he would say when he stepped off the moon’s surface.

“What could I possibly say that would have lasting meaning?” he wondered.

He had prayed that something deep inside of him would come forth to express his feelings. Now, as he looked at the Earth, he was again overwhelmed by the feeling that nothing he said would adequately share what he felt. That was frustrating, because he wanted everyone on his home planet to experience the “magnificent feeling of actually being on the moon.”

He didn’t feel the same as he had before landing on the moon. He felt that he “no longer belonged solely to the Earth.” Now, he felt that he belonged “to the universe.” Although he had notes written on his cuff checklist, he decided to ignore them and speak from his heart.

“As we leave the moon and Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind,” he said. Lifting his boot, he added, “As I take these last steps from the surface for some time to come, I’d just like to record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow.”

As he turned, he saw the small sign pasted beneath the ladder by some unknown well-wishing worker, bearing a phrase that he repeated every time he entered or left the Challenger.

“Godspeed the crew of Apollo Seventeen,” he said, and climbed on board, knowing his would be man’s last footstep on the moon for “too many years to come.”

During their stay, they had covered about 19 miles and collected more than 220 pounds of rock samples. To shed weight in order to get off the moon safely, they tossed expensive gear out of the spacecraft, including cameras, tools and backpacks. There was just enough fuel to get into orbit, with almost no margin for error, so the overall weight of the spacecraft, its passengers and cargo of rocks was critical.

The next day, Dec. 14, Cernan and Schmitt got ready to depart. At 4:56 p.m., Cernan pressed the ignition button, the LM’s ascent engine fired, and they vaulted from the surface, heading into orbit. After linking up with Evans, they remained in lunar orbit for two more days to finish Apollo’s exploration of the moon. After a behind-the-moon transearth injection burn of the rocket engine hurled them out of lunar orbit, on the return trip, Evans did a spacewalk to retrieve the film and experiments from his days in orbit.

After his memorable trip, Cernan was disappointed when they held a televised press conference, but the networks didn’t find time to put them on the air. They splashed down in the Pacific on Dec. 19, 1972, bringing an end to an historical era. Two days later, back at Ellington, several hundred people welcomed them home.

After Camelot

In later years, Cernan would be asked many questions about Apollo 17. One was if getting a scientist to the moon had been the right decision.

“We made a good team, because with his geology background and my geology training, we were able to pick up a lot of things that a lot of people may have missed,” he said. “And he did a good job with the spacecraft. We accomplished everything we wanted to accomplish and it turned out to be a very significant scientific mission. We broke all records for staying on the moon and spacecraft work; most of (the experiments) worked near flawlessly.”

Cernan said that after going to the moon, he’s always felt there were two different space programs, one physiological and one psychological.

“When you head out from the Earth at 25,000 miles an hour, to rendezvous with another planet out there we’ve chosen to call the moon, things do become different,” he said. “In Earth’s orbit, it’s phenomenal. In a 24-hour day, you travel 18,000 miles, traversing through 16 sunrises and sunsets. Every 90 minutes, you fly through a sunrise and sunset. You fly over rivers, coastlines, lakes, peninsulas, cities; if you’re lucky, you might even get a glimpse of your own hometown. But you’re still only 150 or 200 miles above the surface of the Earth—which at the time is pretty spectacular.”

He said that while in Earth’s orbit, you don’t really “see” the world. At some point, after viewing a “slightly curved horizon,” suddenly it somehow closes in on itself.

“You don’t see the world until you see it in its entirety,” he said. “As the horizon closes in on itself, you’re no longer flying over rivers, coastlines and cities; now you’re beginning to look across oceans and continents. You can literally look from one coast of North America to the other coast.”

Then, you begin watching sunrises and sunsets happening almost simultaneously on opposite sides of the world.

“It’s an overwhelming experience to watch a sunset on the east coast of the United States and the sun rise on the east coast of Australia, almost at the same instant,” he said.

As you head out, the blue sheens of oceans and the whites of the snow and the clouds dominate Earth. After a three-day trip to the moon, as you look back, you’re no longer looking at North and South America.

“You find the Earth is revolving, very mysteriously and yet very majestically, on an axis you can’t see,” he said. “All of a sudden, as the Earth turns, you look at Australia and Asia and Europe and the entire continent of Africa. You can look from the icebergs of the north to the snow-covered mountains of the pole at the south. It’s just an awe-inspiring, overpowering experience.”

That’s just the journey there.

“And then you get to the moon, and all of a sudden, for the first time, you’re standing on something that is not Earth,” he said. “You can climb the highest mountain of this planet of ours, or swim to the depths of the deepest ocean, and you’re still on planet Earth. But when you go to the moon, you’re on another body in this universe; it’s solid, and you can walk on it.

“And then you look over your shoulder, and you’re surrounded not by a blue sky, but by a black sky. You’re in sunlight, surrounded by the blackest black you can conceive in your mind. No one confused the blackness with darkness; it’s a blackness that is the endlessness of space and time. And the Earth is three-dimensional in this blackness; it’s dynamic and alive.

“It captures you, but you don’t understand it; you can’t show it to anybody, but you know it exists, because you saw it with your own eyes. Science and technology got you there, but it’s like you’re standing on a plateau where science has met its match.”

His experiences brought him to a conclusion.

“The Earth doesn’t tumble through space; it moves with logic and certainty and with beauty beyond comprehension,” he said. “It’s just too beautiful to have happened by accident. There has to be somebody bigger than you and me that put it all together. There’s no question in my mind that there’s a Creator of the universe. There’s a God up there. Someone—some being, some power—placed our little world, our sun and our moon where they are in the dark void.

Eugene Cernan and Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt prepare the lunar roving vehicle and the communications relay unit mission simulation. Standing to the left, support team astronaut Gordon Fullerton discusses test procedures to be performed.

“The scheme defies any attempt at logic; it’s just too perfect and beautiful. I can’t tell you how or why it exists in this special way, but I know, because I’ve been out there and I’ve seen the endlessness of space and time with my own eyes.”

Although a Catholic, Cernan stresses that he’s not “an incredibly religious person,” and that his statements aren’t of a religious nature, but of a spiritual nature.

“Religion is manmade,” he said. “The Creator I’m talking about stands above all those religions. I believe you can address that Creator in any way you want.”

Cernan also strongly believes that there’s definitely life out there elsewhere.

“Statistically, there has to be,” he said. “Mathematically, when you look at all the stars and the planets— jillions and trillions of them out there— there has to be life out there somewhere else. If you believe as I do, that there’s a Creator of the universe, how can we be so arrogant to believe that that God, that Creator, created life here on Earth and not somewhere else?”

Cernan said he came to these conclusions on Apollo 10, before ever landing on the moon.

“How about going out there a second time, to see if those feelings were real?” he said. “Only John Young and I literally got to the moon twice. So you get a chance to challenge those feelings. Now, other people come back feeling differently. That’s just the way I felt.”

Another thing he felt, especially immediately after returning from the moon, and knowing he’d never go back, was a “yearning restlessness” for his “own little Camelot.”

“That was my home,” he said. “That valley in the northeastern corner up there is where I lived for three days.”

Of course, there are also skeptics who have asked Cernan, “Did you ‘really’ go to the moon?”

“You don’t ever have to defend the truth, but I could tell you where the flag is,” he said. “I can tell you where I put my daughter’s initials in the sand. Nothing is ever going to blow them away.”

Searching for the “next big thing”

Cernan said that trying to exist within the paradox of being in this world after visiting another may be why some moon voyagers tend to be reclusive. He also says it’s no wonder astronaut Alan Bean later became an artist.

“He expresses in art and in painting what I try to express in words,” Cernan said.

After Apollo 17, Cernan spent years searching for the “next big thing” to replace that adventure. But as far as finding a “suitable encore,” understandably, nothing has ever come close.

“It was tough to find something that truly matched both the challenge and the sense of accomplishment of having done something like going to the moon,” he said. “I’d flown three times, walked in space, been to the moon twice. Where do you go and what do you do? What’s the next challenge after you go to the moon? It was tough to find one. Quite frankly, I’m not sure there was anything out there that would match having gone to the moon or what I did by the time I was 38 years old.”

That included becoming the youngest captain in the Navy when he made that rank at the age of 36, after just 14 years with the Navy. A few months after returning to Earth, the Apollo 17 crew made a tour across America of 53 cities in 29 states. Then, after they were guests at a White House state dinner, the president sent them around the world on a flag-waving tour.

Even before the launch of Apollo 17, Skylab and a joint Soviet-American orbital venture were being planned. Following Apollo 17, Cernan served on the negotiating team representing the American astronauts of the long-awaited joint venture with the Russians, known as the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. From 1973 to 1975, he traveled to the Soviet Union numerous times.

As far as what he wanted to do in the Navy, Cernan was still young, and had a desire to go back to flying.

“But I was too senior to do that,” he said. “So, what was the next best thing? Well, I thought, ‘Maybe they can teach me how to drive an aircraft carrier.’ It seemed like a great challenge, but it was a little unrealistic. There were peers of mine who were staying on in the Navy who had worked and worked to get to that point. Why would I be so privileged to be able to be in command of an aircraft carrier?

“So those things were somewhat out of reach. Plus, by the time I got 20 years in the Navy, I was ready to make admiral; admirals don’t command aircraft carriers. It’s too junior for them. So it was a catch-22 for me.”

What the Navy said they wanted was for Cernan to head to Washington D.C.

“Senator Warner, who was at that time Secretary of the Navy, got a hold of me and said, ‘Get your butt back here; we’re going to put you in charge of the Navy space program,'” he recalled. “Well, the Navy space program, at that point in time, was a desk in Washington, D.C., although a two-star admiral ran it.”

Cernan decided instead to retire from the Navy. He left NASA in June 1976, and was soon executive vice president of Coral Petroleum.

“It was a small company, but it did very well,” he said. “In about ’81, before the bottom fell out of the oil industry, I felt I had to get back in the aviation side of the business.”

Cernan talked the owner into acquiring a used Lear 24.

“Then, about a year later, as we grew, we bought a Lear 35. Of course, once we had the airplanes, I had to get qualified,” he smiled. “I went to school, got qualified and hired a couple old Navy buddies of mine who had retired as pilots. But every time I was in the airplane, I threw one of them out or in the back seat. In those five or six years, I must have gotten about 800 hours in Lears.”

Cernan traveled quite a bit, mainly to the Middle East.

“I did a lot of work internationally for Coral, negotiating both crude oil and product contracts,” he said. “The oil business was a little different, but I was comfortable with people and I had a broad exposure to the international world. You know, once you can deal with people, you can in anything.”

Those travels put some adventure in his life.

“Coming out of Iran, I was stopped going to the airport, right after Khomeini took over,” he said. “A couple of guys, vigilantes of some sort, stuck an M-16 rifle in my face through the window of a cab. Those were interesting days, but very challenging.”

Another aspect of his life was also challenging at that time. With his move into private industry, he found himself away from home as much as ever. In 1977, the Cernans moved from their small house in Nassau Bay to a new house in the upscale Memorial area on the west side of Houston. However, in 1980, Gene and Barbara Cernan separated; they divorced the following summer.

Life for the Cernans had definitely been interesting during his space program years. His memories include playing golf with Bob Hope and cooking pasta with Frank Sinatra. Over the years, their circle of friends grew to include political figures such as Ronald Reagan and Vice President Spiro Agnew, whom President Nixon put in charge of the Space Task Group.

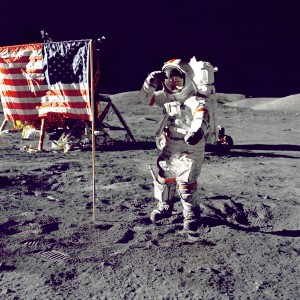

Eugene Cernan salutes the flag on the lunar surface during extravehicular activity on NASA’s final lunar landing mission.

But the relationship also faced many challenges. One was that during much of their marriage, he had been training almost continuously, on either a prime or a backup crew.

“We were engrossed in what we were doing,” he said. “We probably never really understood what our families were going through or gave much thought to it. When we were walking on the moon, having a good time, our wives had to come out, look pretty, be nice to the press and create a wonderful image. When they were asked, ‘How are you?’ it was, ‘Well, we’re pleased… happy…’ and whatever else they were supposed to be.”

In the meantime, Barbara Cernan wanted an identity of her own. Over the years, while her husband was active in the space program, she was recognized as a leader among the other astronaut wives. During her first speech, in 1968, seven years after they married, she told the audience, “Being an astronaut’s wife means living alone most of the time. … It means putting your own ego on the shelf while the world worships your man. … It means that you raise your children alone…deal with money problems and family emergencies…worry whether he is keeping safe, and wait at night for the telephone to ring, to hear your husband’s voice, because that’s as close as you’re going to get for another week.”

She added that one problem with being an astronaut’s wife was that you constantly endured the pain of attending funerals and seeing other wives become widows, fearing the same thing would happen to you.

“Quite honestly, I don’t think they got enough credit for raising families while we were training,” Cernan said. “We were gone eight days a week. We’d leave on a Sunday afternoon and come back on Saturday, and want a home-cooked meal. They’ve been taking the garbage out and the kids to school and we never even thought about taking them out to dinner. We were ‘tunnel-visioned,’ not only to a great extent to what was going on in the rest of the world, but what was going on within our own families.”

Cernan believes that maybe 50 percent of the men in the space program from that period eventually ended up getting divorced. Like Cernan, many didn’t separate until after they were out of the space program.

“It wasn’t a façade,” he said. “I don’t think people held it together because we were supposed to because we were in the space program. I think it was a legitimate desire to be part of each other’s lives at that point in time. I think when things broke apart was after we got back or after it was over. … I think most of the people got divorced after they were mainly through doing what we did back in the 1960s and 1970s.”

Other new beginnings

In the 1980s, Cernan’s ventures included starting an airline with a few friends. Air One was based in St. Louis.

“We catered to the business man—all big seats; we flew standard coach fares for first-class service,” he said. “We had 727s.”

They started out flying St. Louis/Kansas City and soon added other routes to their schedule. The airline did well for over three and a half years.

“Then we became a thorn in TWA’s side,” Cernan said. “Every time they flew the same destination we flew, within plus or minus two hours of our departure time, they cut their coach fares in half. They didn’t touch their first-class fares.

“Not long after that, we found how price-sensitive the industry really was. They took back a lot of those first-class passengers, whose bosses said, ‘Hey, you could fly for half the fare that Air One’s charging you, even though you’re flying first-class.’ We lost a big contingent of people, and we went out of business.”

In 1981, Cernan started the Cernan Corporation. By then, he had hired Claire Johnson, “A petite Tennessee dynamo,” who remains his executive assistant today. Three years later, he met another woman who would become a huge part of his life. He married Jan Nanna in 1987. The marriage gave him two additional daughters, Kelly and Danielle.

Cernan now has nine grandchildren.

“One of my youngest grandkids loves to fly in the front seat when I fly,” he said. “He told me, ‘When I grow up, I want to be a cowboy and a pilot.’ I say, ‘Well, what kind of pilot?’ He says, ‘I want to be a Navy pilot.'”

Cernan smiles at the comment, thinking back to his early days, and his desire to fly off aircraft carriers.

“To me, that’s just one step beyond being a pilot,” he said.

Cernan’s business interests are in Houston, and they have a 400-acre ranch just south of Kerrville (about an hour northwest of San Antonio), Texas, complete with longhorns and never without at least one dog. The Labrador lover has had several over the years, but says he’s now “looking for a playmate.”

“I had three Labs here, but we lost two of them recently,” he said. “They were getting old, and about a month or two apart, we lost them both. We have the pup of one of them. Tejas must be nine years old now.”

Over the years, one Labrador or another has accompanied him when he’s flown in his Cessna 421, which he’s had for about 13 years.

“It’s an oldie but a goodie,” he said.

The last few years also provided him with other flying opportunities. Several years ago, Cernan began doing some marketing work with Bombardier and working with their Learjet demo team.

“Along the way, I said, ‘In order to help you market a product, I’ve got to know how good the product is.’ That was my way of getting in the cockpit,” he said. “You know, you can’t (credibly promote) something unless you know something about it, particularly airplanes. You have to fly; you have to know the airplanes.”

Happily, Cernan went back to school.

“I’m living my second childhood,” Cernan said a few months ago, prior to triple bypass surgery, from which he’s recovering splendidly. “I’m a card-carrying captain on the Lear 45 and 40. I’ve flown a whole suite of airplanes at Bombardier, all the way up to the Global. I’ve flown the 60 and the Challenger 300, which is their newest airplane in the mid-size class.”

In 2004, Cernan and three other people made up a crew that flew the Challenger 300 to the Singapore Air Show.

“We flew it all the way across the Pacific,” he said. “We just changed seats around, so I got a lot of time in the 300. These are as magnificent flying machines as I’ve ever flown!”

Cernan said that one of the most important things he’s done with Bombardier is participate over the last several years in their Safety Standdown, held each October in Wichita. Operators of any type of business aircraft are invited to attend this safety seminar free of charge. The three-day program features industry experts and offers both knowledge and skill-based seminar modules. The objective is to help reduce the number of accidents attributed to human error.

Cernan has worked closely with Bob Agostino, director of flight operations, Bombardier Business Aircraft, who says they modeled the program, begun about nine years ago, after a military standdown concept. The initial concept for a standdown was corrective action in response to an accident.

“We thought, ‘Why don’t we have the standdown before the accidents?'” Agostino recalled.

Initially, the seminar was offered to demonstration pilots, but grew to include test pilots as well, and later, customers that showed interest. Finally, it was opened to the public. Last year, over 400 attended the Safety Standdown, including representatives from NASA, the U.S. Air Force and Navy, the United States and Canadian Coast Guards, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

“Three of the top five Fortune 500 companies were represented,” Agostino said. “Forty-seven percent of the people who attended last year did not fly a Bombardier product.”

Agostino said that Cernan, who has been their keynote speaker several times, has been a big part of the program.

“We’ve built a module around him,” he said. “When Gene gets up in front of a crowd, he talks about some of the mistakes that were made on Gemini 9, Apollo 10 and Apollo 17. Aviators are an interesting lot; the more esoteric the group, generally the larger the egos. When they hear somebody of incredible stature and accomplishment get up and say, ‘Hey, if this can happen to me, I damn well guarantee it can happen to anyone,’ it gets their attention. Gene has been a huge asset.”

Agostino describes Cernan has being “sincerely inspirational.”

“We run into all kinds of people in our business, and all kinds of pilots,” Agostino said. “In my entire 30-plus years of flying jet airplanes, I’ve never met anybody like Gene who is truly a consummate professional aviator and has the humility he has.”

In 2004, Cernan spoke on the need to be “the best,” and the importance of “passion.”

“I talked about the importance of accepting nothing other than being the best—but, at the same time, knowing your own limitations,” he said.

He also focused on “professionalism.”

“If you’re going to get into this industry, number one, you have to have the passion to be the best; it takes that passion to be a professional,” he said. “Just because you fly higher, faster and further than anyone else, doesn’t mean you’re a professional. You have to be good at what you’re doing, or you shouldn’t be doing it.”

Cernan is also a co-owner of Jet Fleet International, a company that negotiates preferred fleet pricing with aviation suppliers on behalf of hundreds of private and corporate jet owners worldwide. The alliance partners consist of contract fuel programs, pilot training, flight planning, weather data, safety auditing/consulting, enhanced vision systems, emergency medical equipment, satellite communications, noise cancellation headsets, avionics upgrades, and aircraft maintenance. Cernan co-founded the Los Angeles-based company with Bob Hoover in 2003, after Finn Moller, who is president of JFI, introduced the idea to them.

“I think we have some really good alliance partners, and we have some good programs now that are really beginning to pay dividends, in terms of what we can do for the people that are members of JFI,” Cernan said.

Aviation and education

Since he’s been out of the space program, Cernan has been involved heavily in aviation education.

“There’s almost an involuntary attraction that drags me into it,” he said.

He’s on the board of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and of the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola. He does a lot of public speaking, particularly with young people as his audience, and has been a “hero speaker” for Young Eagles.

He describes the fascination with aviation and space as a “romance.”

“It’s a romance that we all have with something unique and different, and it always has been, from the day the Wright Brothers first flew,” he said. “It’s that romance with aviation that motivates and attracts and stimulates these young kids to dream about doing it. That’s what Young Eagles is all about. When you realize you have an opportunity to stimulate the hearts and minds of young people, it really becomes a responsibility.”

Cernan said that the Wright brothers’ greatest legacy was “motivation.”

Take out space

“To me, the real legacy of the Wright brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk is the inspiration they provided to people, particularly young people, even a hundred years later,” he said. “The inspiration to dream about doing the impossible, about reaching further than you’ve ever reached before.”

He said it’s thrilling to get youth excited and motivated about aviation.

“I try to leave them with a few things they’ll remember, like ‘Do your best.’ That’s what my dad told me to do,” he said. “And, ‘You never know how good you might be.’ There’s a little slogan I’ll leave them with: ‘No matter what you do, it doesn’t make any difference—in the classroom, on the football field, wherever—always shoot for the moon. Because even if you miss, you’ll land somewhere among the stars.’ That’s another way of saying, “Do your best, because you never know how good your best can really be.”

One example Cernan uses is the relationship that developed between him and Alan Shepard. He goes back particularly to the night in January 1971 that he stood companionably with the first American in space, near the Saturn V Shepard was to fly on Apollo 14.

“Ten years earlier, when he flew, I didn’t even know who he was,” he said. “That night, I stood there as his equal, his backup commander. Not only was I his equal, but I had flown twice, walked in space and been to the moon, and he only had 16 minutes of space flight experience. I tell kids, ‘Don’t count yourself out. Just go out and do your best and you never know where you’ll land.'”

Read more of Cernan’s history in “The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America’s Race in Space.” Published in 1999, the intriguing story was written with Don Davis. To purchase the book, visit [http://www.genecernan.com].

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part I

Gene Cernan: “Always Shoot for the Moon” Part II