By Tom Wylie

When Gilbert Utterback was born in 1930 in Perry, Mo., aviation was still young. Only three years earlier Charles Lindbergh had made the first non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in the Spirit of St. Louis, named for the big river city not all that far southeast of Perry.

It was only 24 years before Lindbergh’s flight that Orville and Wilbur Wright made their preliminary pencil sketch of the Wright Flyer on brown wrapping paper. On Dec. 17, 1903, the duo made history with four short flights with their flyer at Kitty Hawk, NC. Incidentally, there is a direct connection between these two events—powering the Ryan NYP that Lindbergh flew to Paris was a single Wright J-5-C engine.

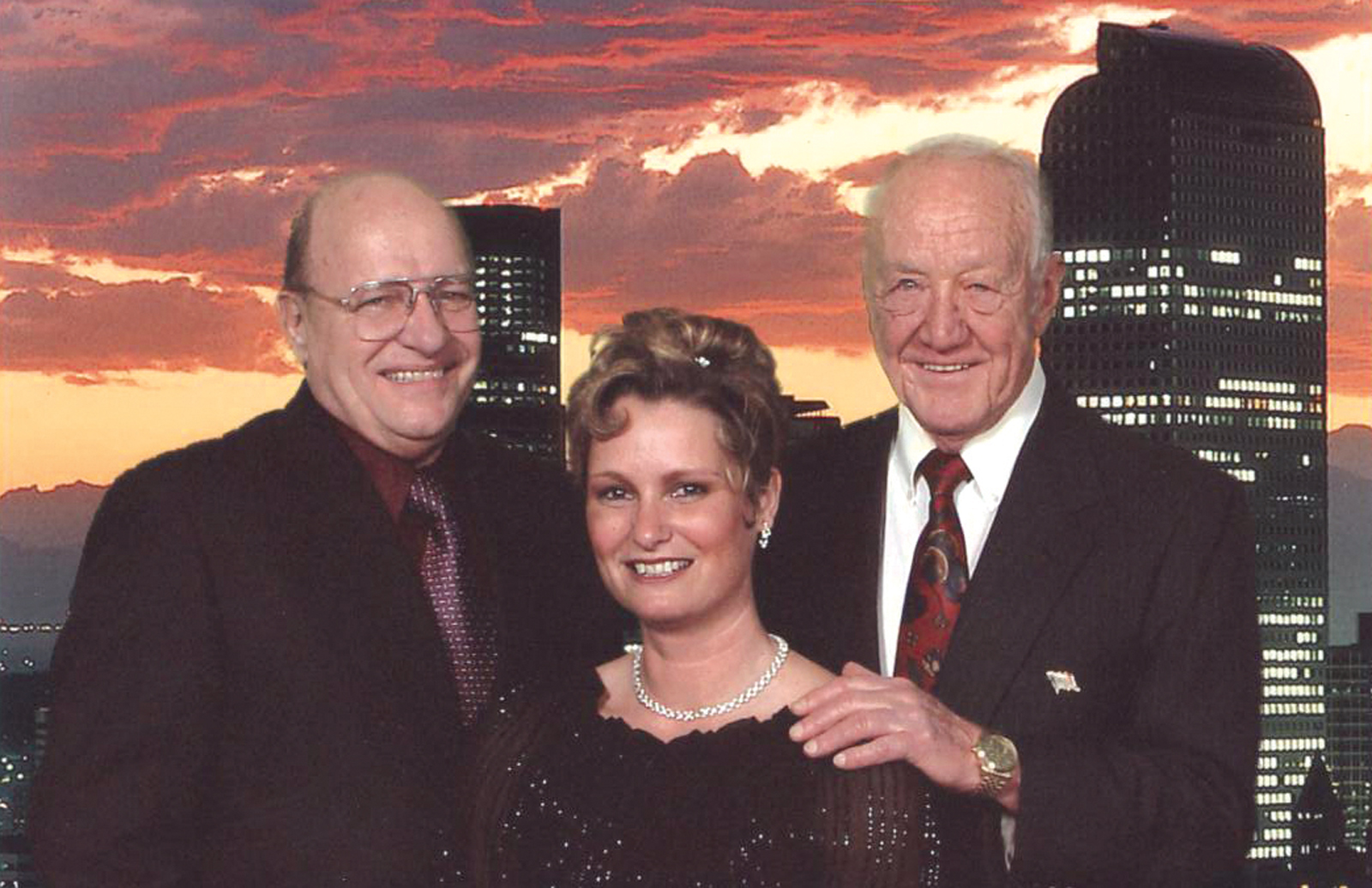

With humble beginnings in Missouri, Gilbert Utterback’s story and contributions to General Aviation have made an everlasting impression. He went quietly about learning the FBO business from the ground up and rose to be the president of the Denver jetCenter. Flight department managers and pilots from around the nation know him. Most call him friend; to them, he is simply “Gil.” Few, if any, call him “Mr. Utterback.” A classic American success story, Utterback’s starts during the Great Depression and weaves its way through an extraordinary life and career accomplished by character, integrity, self-improvement and persistence.

Utterback’s father was a coal miner who earned just one dollar a day, but felt fortunate to be employed during those hard times. Perry, Mo. was a very small community in those days, decidedly rural. Only about 950 people lived there. It was barely large enough to call a town. After Utterback’s freshman year in high school, the family relocated to Monroe City, Mo. It was a larger small town with a population of about 2,200, and Utterback graduated there in 1948.

Part of a revolutionary time

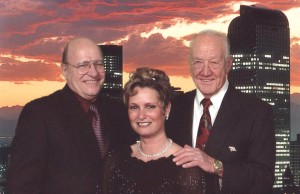

Standing: Jim Buswell, Gil Utterback, Pat McCabe, Aaron Woods and Larry Carwin Sitting: Pat McCabe and Michelle Favatella

Hannibal, Mo., Mark Twain’s birthplace and childhood home, is about 20 miles east of Monroe City on the banks of the Mississippi River. If you think a lot of aviation history was compressed into the years between the Wright brothers and Lindbergh, think about this: Mark Twain was born in 1835 and died in 1910. At one point he served as a steamboat captain. Twain traveled by stagecoach and railroad, and lived long enough to know about automobiles and airplanes. In less than three generations, beginning in Twain’s lifetime, our nation went from horses and steam power to moon rockets and spacecraft.

Drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War, Utterback went through basic training at Fort Riley, Kan., and went overseas in an infantry unit—not to Korea, but to Austria.

“It was good to be in a place where no one was shooting at me,” he said.

He became the company clerk with the rank of corporal. Discharged from the Army and back home, Utterback found work at the Caterpillar Tractor plant in Peoria, Ill. He discovered that it was not work he wanted to do for the rest of his life. To better himself, he went to a two-year business school in Quincy, Ill., and learned accounting.

Utterback married Martha Stickler in 1958, and they made their home in Monmouth, Ill. The couple began rethinking their lives. They were newly married with children in their future (daughter Karen and son Kevin were born to them in due time). Utterback was concerned about his job. A friend of had spent some of his Army time in Colorado. A good place to live, he said, with a good climate and lots of sunny day and opportunities to get ahead. So in 1959 the Utterbacks moved west to Denver.

Utterback found work quickly. Combs Aircraft at Stapleton Airport wanted to hire an accountant, but couldn’t hire him for the job immediately. Combs put him to work as a sales clerk in the parts department. Utterback learned every aspect of the business, working as an accountant, parts manager and the aviation business manager. He earned his pilot’s license in 1964 with a desire to see aviation from the point of view of those he served.

“I enjoyed flying,” Utterback said, “but I was always a low-time pilot.”

Combs Aircraft was one of the largest Beechcraft distributers in the country. In 1968, Charles Gates bought Combs Aircraft, then he and Harry Combs purchased Learjet. Olive Ann Beech, the CEO at Beechcraft, wasn’t happy that one of her distributors was under the same roof with Learjet. She viewed this as a”competitive conflict.” Combs couldn’t convince her otherwise, and as a result she cut her business ties with Combs Aircraft and established her own regional distributorship: Denver Beechcraft.

During this upheaval, Utterback was offered a career ladder at Denver Beechcraft and took on the challenge. Now he burnished what he already knew and built upon it, working as the parts manager again, operations manager and business manager. Jeffco Beechcraft, a subsidiary of Denver Beechcraft, was established as an FBO at the Jefferson County Airport in 1980, and Utterback moved there to serve as general manager.

Denver Beechcraft, still building its business, bought Tiger Air’s FBO at the Arapahoe Airport (now Centennial Airport) in 1984. Utterback was named the general manager of the new acquisition, which they called Beechcraft Air Center-1. Clearly, Utterback had established his credentials in aviation services. He had become the “go to” guy for Denver Beechcraft as it continued to expand its operations.

If you are involved in private aviation, and if you have heard of the concept of “six degrees of separation,” you know that within the GA community there are more like three degrees of separation. Utterback’s story illustrates this principle. His ties to Neal and Linden Blue are a prime example.

In the later years of the 1950s, the two Colorado “Blue” brothers were college students and rookie pilots. They knew Harry Combs and told him of their plan to spend their summer flying to (and over) much of South America in a small Piper Tri-Pacer airplane they were able to borrow. They made the trip, but that is another story.

Thirty years later, the brothers Blue bought three FBOs from Beechcraft. One of those was Air Center-1, which they renamed Denver jetCenter. Larry Ulrich headed up the jetCenter holding company and had known Utterback since he arrived in Denver.

“One of the very first things I did was to appoint Gil to be president of the Denver jetCenter, which proved to be one of the best business decisions I ever made,” Ulrich said.

People like Harry Combs, Olive Ann Beech, Charlie Gates and Neal and Linden Blue invested money in FBOs, and people like Gil Utterback shared their talents and abilities to gain a return on investment. The best FBO chiefs create customers loyalty and bring in more business, and Utterback is the great example.

When 1996 rolled around, Utterback had reached retirement age and was financially able to take the step without worry. Not quite ready to retire, Utterback worked out an arrangement with Ulrich, who took over as Denver jetCenter president while Utterback moved into the position of senior vice president until he officially retired in September 2008.

Do a little arithmetic and you come up with 50 years of aviation service for Gil Utterback. Why, you might ask, would anyone work so many years beyond the normal retirement age? For Utterback, the reasons were the same as they had always been—he loved his work and he loved people.

Sure, he was more than competent. As Ulrich said, “We could always rely on Gil to get the job done right, on time and on budget.”

And by “we,” Ulrich means the clients as well as the company. The FBO business is a demanding customer service oriented business, and all Denver jetCenter customers are VIPs. What distinguished Utterback’s career—and it was his greatest asset—was his consummate way with people. He truly cared for people the people and industry he served.

His job took most of this time, of course. Utterback enjoyed golf, which continues to keep him in touch with friends. His true passion was (and still is) the Centennial Airport Lions Club and its charity work. He has been a Lions member for 30 years. Golf plays a role in the Lions Club charitable outreach, and Utterback is right in the middle of it. He has organized and managed the club’s annual charity golf tournament since its inception seven years ago. The tournament has generated donations of more than $340,000.

Utterback is highly valued for his work ethic in both aviation and the Lions Club. Fellow Lion Kerry Mc Pherson can attest to Utterback’s unwavering commitment. “Gil has been the backbone of our club,” McPherson said.

Within Lions Clubs International, the highest award for humanitarian service is the Melvin Jones Award. The scope of Utterback’s service to others became evident as McPherson continued. “The vast majority of Lions can work a lifetime and never receive this award,” he said. “Gil has received the Melvin Jones Award an astonishing four times!”

It was Utterback’s idea six years ago to have a weekly cookout at the airport as a charity fundraiser for the blind and visually impaired. Just visit the Centennial Airport tower around midday on Fridays from April through September—you’ll likely find Utterback in charge and flipping hamburgers and brats on the grill. Stop by for a brat and help those the Lions are helping. If you don’t already know Utterback, when you walk away after downing the bratwurst, you just might have a new friend.

Author Tom Wylie is a retired National Park Service ranger, biologist and writer. He acknowledges, with thanks, the help and information graciously provided by Gil Utterback, Larry Ulrich and Kerry McPherson.