By James G. Stanley

John S. Anderson spent a lifetime with the growing and changing airline industry before retiring in 1998. He first started with American Export Airlines in 1942.

John Anderson, a docent at The Museum of Flight, spent more than 50 years as part of the growing and changing airline industry.

Anderson, now a docent at The Museum of Flight, grew up in Asheville, N.C., building model airplanes and looking skyward. His first flight, in 1929, was in an old Curtiss pusher seaplane, operating off the beach of one of the small islands between Miami and Miami Beach.

“My family drove down to Florida on vacation during the Christmas holidays,” he said. “After that flight, I was hooked!”

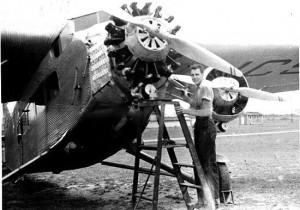

By the time he was 9, he regularly haunted a local airport in Asheville, watching a Ford Trimotor haul passengers and investigating how the old Curtiss OX-5 powered airplanes were made.

“Once, when I was upside down in the cockpit of someone’s Aeronca C-3, investigating whether I was correct in believing that the cables from the control stick to the elevators had to cross over, the plane’s owner grabbed me by the seat of my pants and hauled me out,” Anderson said. “He wanted to know what I was doing. I was sure I was in real trouble, but when I explained what I was up to, he became friendly and showed me anything I wanted to see. I was hoping he would give me a ride, but he didn’t.”

Central Airport

Anderson’s father died in 1937. For family reasons, he moved into an apartment in Richmond while in his senior year in high school.

He rode his bike to school and then to Central Airport in northeast Richmond, where he worked after school, fueling airplanes and putting them in the hangar for the night. After graduation, he worked fulltime and was promised one hour’s flying time per week.

The promise wasn’t always kept, but he was allowed to solo after four hours and 50 minutes flying time—no doubt to keep from using instructor time on a non-revenue student. He was conscientious and rewarded for his efforts with two dollars a week pay, in addition to the flying time.

When a group of Ford Tri-Motor barnstormers known as the Two-Mac Aerial Tours came through Richmond, they offered Anderson a job. He was to help keep the plane flying by cleaning, oiling and fueling it. He sometimes also sold tickets, and was paid $15 per week. If a flight wasn’t full, he was allowed to ride in the copilot’s seat.

American Export Airlines

Anderson enrolled in the maintenance engineering course at Parks Air College in East St. Louis in January 1940, and graduated in March 1942. While there, he became a welder, was licensed as an aircraft and engine mechanic (later aircraft and power plant) and received his private pilot’s license. He also qualified for a radio code license, second class, including instructor rating.

The attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 put any plans he had on hold. He volunteered for the Army Air Corps aviation cadet program, but failed the physical.

When Anderson was 19, American Export Airlines, based in Port Washington, Long Island, hired him as an A&E mechanic. American Export Lines, a steamship company, organized AEA in 1937, to establish service across the North Atlantic.

Anderson began his job with AEA on April 15, 1942, with the proviso that he would be transferred to flight operations as a flight engineer when hiring expanded in that department.

AEA started flying-boat service in June 1942, after several years of political resistance from Pan American Airways. The company flew the new Sikorsky S-44 between New York and Ireland.

AEA was also awarded a U.S. Naval Air Transport contract, using four-engine Consolidated PB2Y-3 aircraft and twin-engine Martin PBMs supplied by the Navy. All AEA operations during the war were conducted under that contract, and all crewmembers were inducted into the Naval Reserve. Included were about 10 of General Chennault’s Flying Tigers, who had returned to the states after the American Volunteer Group contracts had expired.

“Seaplanes were slow,” Anderson said. “The Sikorsky airplane was about as fast as any, cruising at 140 knots maximum, with a range of up to 29 hours.”

When flying westbound from Foynes, Ireland to New York, it wasn’t unusual to have headwinds of up to 70 mph for long periods of time. To minimize the effect of the wind, the planes were flown at 100 to 500 feet altitude. That required constant vigil at night.

Often, an aircraft was forced to climb to prevent the ocean spray from icing up on the wing floats, wing and hull, which would increase drag and fuel consumption. Occasionally they did pick up some ice, and it seemed to take forever for it to completely melt.

On the eastbound flights, they usually had favorable winds. When flying in instrument conditions, they’d sometimes climb to much higher than normally pressurized flight levels to break out of the clouds and permit the navigator to get a celestial fix.

“One night, out of Botwood, Newfoundland, bound for Shannon, Ireland, it was essential to determine our progress or turn back,” Anderson said. “We climbed the Sikorsky to 18,100 feet before breaking out. That was about as high as we could get. The Pratt & Whitney 1830 engines were running at maximum allowable rpm and low manifold pressure with the throttles wide open. Fortunately, we broke out of the overcast and the navigator got his sight. We were in good position, and we quickly descended down into the clouds to our most efficient cruise altitude, 8000 feet.

Anderson became a flight engineer on Dec. 1, 1942, and continued in that capacity through a long and successful career. Many of his flights left indelible memories. In 1950, he flew on the Korean Airlift, ferrying air-evacs from Tokyo to the United States for additional medical care. The aircraft was the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser. Pressurized to fly above most weather, it had very comfortable berths—usually a total of 28 upper and lower.

“I usually went back at least once on the long flights to say hello to the guys, but in most cases, not much more,” Anderson said.

Those flights usually transited through Wake Island for fuel. On one such stopover, an unusually large number of aircraft were on the ramp. It turned out that President Truman and General MacArthur were having their famous and rather unpleasant meeting there.

In 1945, when American Export Airlines was awarded transatlantic rights to northern Europe, including London, the airline was forced to relinquish its ties with the shipping industry. For that reason, it was sold to American Airlines, and became its transatlantic division, American Overseas Airlines. AOA remained with American for a few years; during those years, Anderson flew as flight engineer on the Douglas DC-4 Skymaster, the Lockheed Constellation and the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser.

Pan American World Airways

Pan Am Captain Paul Roitsch and Sud Aviation test pilot Juan Franchi show flight engineer John Anderson the Concorde flight simulator in Toulouse, France.

In 1950, AOA merged with Pan American World Airways and eventually disappeared within the vast organization. During all the transitions and mergers, Anderson continued his progress toward his final position as Pan Am’s director of flight engineering. He had flown in commercial service as a crewmember on most of the piston-engine aircraft of that era and had moved up to the Boeing 707 and 747 and Douglas DC-8 jets. During the 1960s, he was a member of the Pan Am evaluation team for both the Concorde and American SST supersonic programs.

Anderson believes his Parks Air College education provided a sound foundation for continued learning.

“Looking back on those years, I count the schooling I got from manufacturers as some of the best I could have received anywhere,” he said. “Pratt & Whitney contributed more than any other company, but Wright Aeronautical, Hamilton Standard and Curtiss Electric were very helpful.”

Anderson said that when Pan Am ordered jets, he enrolled in a night college course to learn an entirely “new-to-me” principle.

“It was a general course to prepare me for the comprehensive operations programs offered by Pratt & Whitney and Boeing, in preparation for delivery of the first jet aircraft to an American airline,” he said.

The year 1958 was very busy for the Pan Am jet inauguration team. Before delivery of the first airplane, line crews participated in an intensive flight training course. Because jet aircraft simulators weren’t available at that time, crewmembers were each given about 20 hours of training flights.

Anderson was assigned to an interesting survey and publicity flight, which preceded inauguration of regular airline service. The job involved ferrying a 707 from New York to Washington National Airport (DCA) for a christening ceremony by First Lady Mamie Eisenhower, and then to Washington-Baltimore International Airport (BWI) to pick-up a group of U.S. senators and newsmen for a trip to Brussels, Belgium. BWI was chosen for its long runways, which could accommodate the heavily loaded plane.

The only problem was that the 707 required a start cart for the engines, and the only cart on the East Coast, aside from those at New York’s Idlewild (now John F. Kennedy), was at Washington National. The plan to solve the problem had all the ingredients for a complete disaster. The 707 was to start engines at DCA and fly the 25-minute flight to BWI, while a van with a police escort transported the start cart to BWI. Surely a long delay was in the making. But by the time Anderson completed the aircraft logbooks and computed the required fuel uplift at BWI, he heard the sound of sirens heralding the cart’s arrival.

The crew took the senators to Brussels, where the 1958 World’s Fair was in progress. They also flew several groups to Paris and circled the Eiffel Tower for publicity flights. On October 19, they returned to Idlewild. On that flight, Anderson met Juan Trippe, Pan Am’s CEO.

The following week, on Oct. 27, 1958, Pan Am made the first commercial jet flight by an American airline, from New York to Paris. Anderson was positioned in Paris and was a crewmember for the first westbound crossing.

When the Concorde supersonic aircraft was in development by France’s Sud Aviation and British Aircraft Corporation, Pan Am was interested in its purchase. Anderson was assigned to Pan Am’s three-man Concorde evaluation team, which made a number of trips to the construction facilities in Bristol, England, and Toulouse, France. The team hammered out specification documents and checked out the program’s progress over a period of six years.

“As flight engineer consultant, it was a privilege to be an observer on the first supersonic flight demonstration for any airline,” Anderson said. “This occurred when it achieved Mach 1.47 in the test program. I made four subsequent flights on the Concorde with other members of our team, but we finally canc`elled the contract for the airplane.”

On one of the Concorde flights, they departed over Cork, Ireland, and then headed down toward North Africa, and across the Bay of Biscay. They reached Casablanca in a little over half an hour.

“During the war, I had flown the same route, from Foynes, Ireland, to Port Lyautey, Morocco, in the Sikorsky S-44 seaplane, in 10 and a half hours,” Anderson mused. “In those days, there was some very real concern over the possibility of being shot down, because the Germans patrolled the Bay of Biscay and sometimes attacked transiting planes.”

John Anderson (second from left) discusses Concorde flight evaluation with (L to R) Andre Turcat, Sud Aviation chief test pilot; Paul Roitsch, chief pilot, technical, Pan Am; and Brian Trubshaw, chief test pilot, British Airways.

Anderson’s work on the Concorde closely paralleled a later assignment, comparing the two American SST programs. Airlines were invited to study proposals from Boeing and Lockheed, and were asked to recommend which proposal would be better for commercial service. Participation in the American SST program went on for several years, and necessitated extended trips for engine evaluations in Evendale, Ohio, and West Palm Beach, Fla.

The entire evaluation team agreed that both the Lockheed rounded-tip delta wing model and the Boeing swing-wing model were impressive. The GE engine powered swing-wing earned Boeing the approval, but the United States Senate cancelled the project because of ecological concerns.

Anderson wasn’t a member of the evaluation team for the Boeing 747 program, but he was assigned to write the 747 operations manual’s engine section. The engine design and construction program had moved too rapidly, causing the 747’s engine to be unreliable. Even after going into the flight certification phase, the engine mounting system had to be drastically modified, and the variable stators operation had to be improved in order to eliminate violent engine stalls when thrust was reduced. Engine thrust reversers constantly failed. These problems concerned many in the first days of 747 operation.

Meeting Lindbergh

Anderson described one commercial flight in February 1974, on a 747 from Frankfurt, Germany, to New York, as “a trip to remember.” The ramp was icy in Frankfurt, and it took a long time for the tug to push the plane back from the gate.

During that time, the purser came to the flight deck to confirm that the passenger emergency procedures briefing was complete. Then she made the surprise announcement that Charles A. Lindbergh was onboard. Shortly after that, the captain decided to explain the delay to the passengers and let them in on the secret.

“You’ll be interested to know that today we have General Charles Lindbergh aboard,” he said.

Second later, the purser returned, in dismay.

“Sir, you’ve really done it!” the purser said. “Lindbergh is mad as hell down there. He hates notoriety when he’s traveling.”

After takeoff, they were climbing through 10,000 feet when the purser returned with a note, which said, “Dear Captain, inasmuch as you have made my life miserable down here, I wonder if I might come to the flight deck for the flight.”

The captain quickly agreed. A few minutes later, Lindbergh came to the flight deck and took a seat in the observer’s station. The climate was cool and formal between Lindbergh and the captain, and the distance to the first officer was too great for easy conversation. Anderson felt lucky to have Lindbergh’s company for the next eight hours.

“Lindbergh had been in Germany for an ecology meeting and was returning to his home in Connecticut,” Anderson said. “He was 72, but he looked frail and considerably older than that. I learned later that he was suffering with the cancer that killed him in August of that year.”

They discussed ecology, and Lindbergh told Anderson he was focused on reducing gasoline consumption worldwide. As they flew along Long Island Sound on the way into Kennedy Airport, Lindbergh looked out the window at the scattered lights in the darkness.

“I’m trying to see if I can pick out my house,” he said. Then, all of a sudden, he gleefully exclaimed, “Yes, there it is! See? Out on that point of land!”

Anderson looked and was able to see the lights on Lindbergh’s property near the waterfront.

Retirement

Looking back on his 27 years working with the 747 aircraft, Anderson said he was fortunate to have been involved.

“It’s truly a great achievement,” he said.

After stepping down from his director’s job, Anderson won his bid for Miami as home base and resumed flight engineer status. In a cost-saving effort in 1982, Pan Am cut back its operations, and offered him a very attractive early retirement package. Anderson took the offer and retired on Dec. 31, 1982, after 40 years and seven months of service.

Shortly thereafter, he took a job with Overseas National, to fly as flight engineer on 747s during the Hajj project. They flew Muslim pilgrims from Nigeria to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for visits to Mecca. He was based in Jeddah for the short program.

A small newly-organized airline, Tower Air, then invited Anderson to fly as flight engineer. The airline grew into a fleet of 20 747s. Anderson became chief flight engineer and stayed with the company for almost 14 years. Tower Air gave him a wonderful party when he retired on May 11, 1998, his 76th birthday.

Somewhere along the way, Anderson became an expert photographer. One of his favorite photos is of Concorde 214-G-BOAG, on final to Boeing Field on Nov. 4, 2003. The British Airways supersonic jet was making its last landing approach, after a record-breaking flight from New York, over northern Canada, to Seattle, in 3 hours, 55 minutes and 12 seconds. The decommissioned aircraft remains on permanent display at The Museum of Flight.

In 1999, Anderson volunteered as a docent at museum. Soon, he became especially interested in the development and operation of the Lockheed Blackbird, the Mach 3.2 reconnaissance and photographic plane. He traveled to Edwards Air Force Base to climb into the cockpit of one of the few remaining flyable versions of the Air Force model SR-71, and actually flew the SR-71 simulator.

In August 2000, Anderson published a 66-page comprehensive treatise, covering technical and operational aspects of the Blackbird series of aircraft, from the original A-12 version, flown by the Central Intelligence Agency, to the SR-71, flown by the Air Force. The Museum of Flight displays an MD-21 version of the Blackbird. It’s the only surviving model with a ram jet–driven surveillance drone mounted on the after fuselage. Anderson compiled his study to assist other docents when they conduct public tours, and to be able to discuss in depth most aspects of the program.

He certainly achieved his goals, and more!