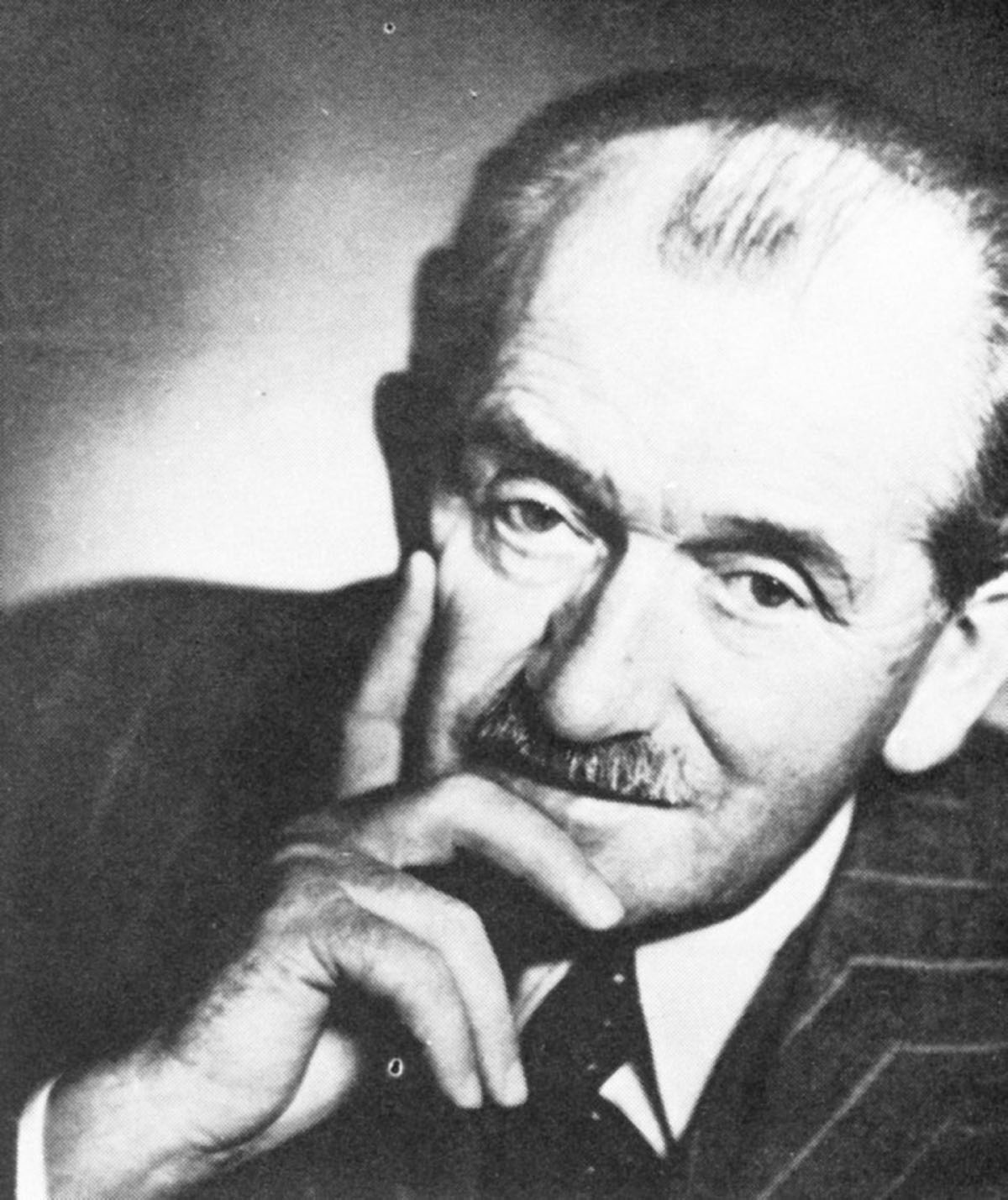

When Professor Ferdinand Porsche (shown) died in 1951, Ferry Porsche assumed his place in the emerging Porsche empire.

By Daryl Murphy

Unless you’ve been living in another galaxy for the past five decades, you’ve heard of Porsche automobiles and their reputation in endurance racing. With wins at races like 24 Hours of Le Mans, Daytona 24 Hours, 12 Hours of Sebring and Targa Florio, Porsche has triumphed at race venues more times than virtually any other make of car. Porsche’s Carrera model was named to commemorate the marque’s successive triumphs in Carrera Panamericana, the Mexican Road Race held during the early 1950s. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche may have been the most prolific designer of the 20th century. He was obsessed with mechanical perfection, no matter the cost in time or money. In 1900, at the age of 25, the Austrian designed a front-wheel drive automobile powered by electric motors mounted in the wheel hubs. His 180-hp Austro-Daimler aero engine, designed in 1913, was the prototype of most German aircraft engines of World War I. He produced the fantastic S series for Mercedes, before returning to Austria to engineer farm tractors for Steyr.

Porsche experimented with aero engines, airships and helicopters and designed the Tiger Tank, a self-propelled gun, and the prewar 545-hp mid-engine Auto Union Grand Prix and Land Speed Record racecars. He was a pioneer in front-wheel drive, four-wheel drive, four-wheel brakes, automatic transmissions and streamlining, and he created the Volkswagen.

Porsche was arrested along with other prominent Germans after the country’s surrender in 1945, and was jailed by the French. After he agreed to develop a Grand Prix car for an Italian industrialist, he was freed, although his son Ferry had to raise a million-franc ransom to insure his release. His spirit broken, Dr. Porsche died in 1951, and Ferry assumed his place in the emerging Porsche empire.

In the early ’50s, Porsche’s reputation for reliability in racing hadn’t yet been established. The first race car example had come from Gmund, Austria, late in 1948. The car was equipped with a tuned version of the Porsche-designed 1,086cc four-cylinder Volkswagen engine that produced an anemic 44 horsepower. The power plant hadn’t been designed to withstand the often unreasonable loads imposed during the long hours of endurance racing.

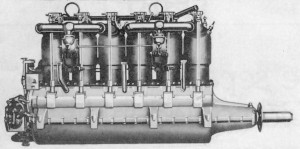

The Porsche-designed 180-hp Austro-Daimler aero engine of 1913 was the prototype of most German aircraft engines of World War I.

While improvements were made at a constant rate over the next few years, they were largely based on the needs of European drivers and conditions. By the end of 1952, about 2,740 cars had been built; only about six percent of them had made the crossing to the Americas—primarily to the sports car-rich Northeast and to car-crazy California. The cars were welcomed by enthusiasts who found them competitive on twisty back roads when challenged by American cars with three to five times the horsepower. Owners reasoned that if a Porsche could beat a Cadillac in a race from, say, Elmira to Binghamton, it most certainly could do the same for a longer distance, like the 2,000-mile event called Carrera Panamericana, which roared through the mountains, deserts and jungles of Mexico.

The epic open-road event had started in 1950, when a group of American race drivers and Mexican truck and taxi drivers, plus a scattering of “gringo” tourists, answered the call to see who could be the fastest across the entire length of Mexico, from El Paso to the Guatemalan border. American Hershel McGriff won the 2,135-mile race, in an Oldsmobile 88 that averaged 78.4 mph over the course. The next year, the race was shortened to just over 1,900 miles, and Piero Taruffi and Alberto Ascari upped the average by 8 mph in their Ferrari 212s. By 1952, the annual event had been placed on the international racing calendar and had captured the attention of some very fast factories, including Daimler-Benz, which sent its successful new 300SL sports racers to Mexico for their final racing appearance.

It was also the year Porsche made its first appearance in Mexico. Two 356S owners, Graf von Bercheim and Paul Alfons von Metternich, persuaded the Mexican Volkswagen importer to sponsor their entries. Both cars were likely equipped with race-tuned versions of the 90-hp Super 1500 engines. Bercheim’s was a coupe and Metternich’s a special limited production 356 American cabriolet with aluminum body by Glasser, which suggested the Speedster that would soon emerge. His was also the first Porsche equipped with a synchronized gearbox.

While Porsche still relied on VW to supply its engines, the available Super 1500 model could propel the rear-engine cars to speeds over 100 mph.

Two 1,300-lb French T 15 S Gordinis were also in the sports class. Jean Behra and Robert Manzon drove these tiny bombs, which had 2261cc, 154 hp sixes and tremendous power-to-weight ratio. They raced without riding mechanics and with two spare tires secured to the rear.

Karl Kling’s Mercedes won the overall race in 18 hours, 15 minutes, at an average 102.527 mph, followed by Hermann Lang. The first of four stock class-winning Lincoln Capris was seventh overall in 21:15 at 90.78 mph, followed by Metternich in eighth overall, fourth in Unlimited Sports.

And then there were two—1953 Carrera IV

A 125-hp Fiat V-8 with five-speed transmission powered Ernie McAfee’s Siata 8V Sport in the 1953 race.

When the organizers of the Mexican Road Race decided to diversify, they created two classes for stock and sports divisions, to add parity for the budget racers. The differentiation in stocks was based on horsepower, and in clase sport menor (small sports car class) on displacement at 1600cc (98ci). It was a convenient figure for Porsche and Borgward, two emerging German marques.

Borgward was the first German manufacturer to go into production after WWII. Its sedans were powered by 1500cc and 1800cc fours and a 2400cc six. In 1950, a streamlined 1500 set a dozen international class records at Montlhery, so they were no strangers to speed.

The company had raced its Isabella-based 1492cc pushrod sports racer successfully in Europe, with recent victories at Grenzlandrig and the high-speed Avus circuit, in the hands of Hans Hartmann. He and Adolf Brudes, who was third in the 1940 Mille Miglia aboard a BMW, would be driving a pair of five-speed roadsters in Mexico.

Their main competitor would be Porsche, which was barely five years old in 1953, but busy building a reputation. Porsche had won its class at both Le Mans and the Millie Miglia in 1952, although a failed top gear in the former resulted in the last 200 miles being driven in third gear.

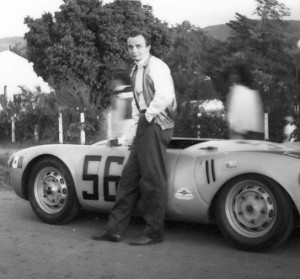

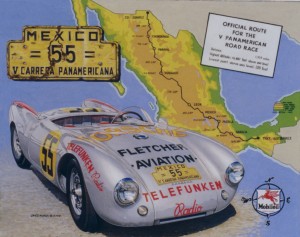

In 1953, Fletcher Aviation, a licensed builder of Porsche engines in the U.S., provided air transportation for key crew members of the German team, shown with Karl Kling’s Por-sche 550.

Ten Porsches were entered in the Pan-Am. Karl Kling, winner of the 1952 race in a Mercedes 300SL, and young Hans Herrmann would drive the two official factory entries—550 Spyders with 1498cc, 78-hp pushrod engines and chassis numbers 03 and 04. Guatemalans Jose Herrarte and Jaroslav Juhan had purchased Spyder coupes 01 and 02—the cars that had placed 1-2 in class at Le Mans. They had been raced extensively in Europe before being exported to the Western Hemisphere (no factory ever gave its customers better equipment than it kept for itself). Manfredo Lippman would also be on the team, driving a 356S.

The balance of the Porsche field was made up of 356s, probably 1500 Supers. Two were lightweight aluminum-bodied coupes, the others steel. Jacqueline Evans de Lopez, an English-born film actress who had married a Mexican, would make her fourth attempt to finish Carrera in her personal coupe.

When the Porsche group arrived in New York from Germany, on its way to Mexico, immigration officials detained Kling, reasoning he looked like a Nazi general who had somehow escaped Allied prosecution after the war. It had been only a few years since Germany was considered the enemy, and Kling had the looks and manner of the Hollywood image of a Prussian officer. After two days he was given the go-ahead.

Jacques Peron entered an OSCA MT-4. The Maserati brothers built the 1,280-lb sports racer, which had a dual overhead cam four of 1490cc that developed 110 hp at 6200 rpm and featured the highest final-drive ratio of any car in the world.

Ernie McAfee, California Siata distributor, entered a Siata 208S, a 1,750-lb sports racer powered by a 1996cc overhead valve Fiat V-8 sleeved back to 1600cc and running in a lightened, 1,600-lb chassis through a five-speed transmission. Fifteen drivers would be vying for a 30,000-peso ($3,866) first prize from the class purse of 68,000 pesos (a fairly menor amount for the menor category).

Survival of the fittest

On the opening leg, Hans Herrmann squeaked out a 25-second win over veteran Karl Kling. Hans Hartmann’s Borgward trailed Kling by nearly 10 minutes in third. Failing to reach Oaxaca in the allowable six-hour time limit for the 329 miles were Jacques Peron’s OSCA, Adolph Brudes’ Borgward and perennial “did not finish” Jacqueline Evans de Lopez. Only the strong could survive leg one of the Pan-Am.

On leg two, however, the best-laid plans of Herrmann and Kling crumbled. Herrmann experienced steering failure and slid his Porsche into a mountain face to avoid plunging off the road. Kling suffered a failure of the right half-axle. That left only Manfredo Lippman in a 356S to carry the colors against the privateers.

Porsche racing director Fritz Huschke von Hanstein put the house mechanics at the disposal of Lippman’s team. McAfee retired the Siata after an accident. The entire class was down to seven cars: six Porsches and a Borgward.

Jaraslov Juhan won leg two, four minutes up on Hartmann in his Borgward, but the overall pace had fallen. Then the two Spyders’ hard-charging drivers went out. Hartmann was keeping Juhan—his only competition at this point—in sight, but the German driver was smart enough to know that a lot could happen before this race was over.

The tortuous run to Mexico City should have been easy for the Porsches, but Juhan finished first, in just under an hour, further off the pace than before. Hartmann once again shadowed him in second, with Guillermo Suhr, Fernando Segura, Jose Herrarte and Salvador Lopez Chavez trailing. Juhan now led the small sports race by slightly more than one and a half minutes, with the third-place car already nearly an hour behind.

Juhan and Hartmann led leg four into Leon. On leg five, the highway was flatter and the Borgward driver became bolder, beating Juhan to Durango by a minute and 10 seconds, closing to within a few ticks of the clock from taking over the lead. Herrarte, Segura, Lippman and Chavez followed.

On leg six, Hartmann began to push, averaging 90 mph and finishing nearly five minutes ahead of Juhan’s Porsche, which had fuel system problems. Hartmann finally took the lead, Chavez’ Porsche expired, and that left just five.

From Parral to Chihuahua, the Borgward picked up an amazing 19 minutes over Juhan’s Porsche, averaging 106 mph. Hartmann was totally in command and had the momentum to run a record-breaking last leg, to smash the Porsche opposition once and for all.

He was roaring along in great style, bent on being the first of the small sports racers to Juarez, when the Borgward faltered, and its engine began running poorly. Hartmann stopped and changed the spark plugs, but the trouble persisted. Running on three cylinders, he proceeded at reduced speed, knowing he had built up more than enough time to win. When he arrived at the finish line, third behind two Porsches, he knew his accumulated time would place him nearly one and three-quarters hours ahead. But the maximum allowable time for the 222-mile leg had been set at three hours; he had finished seven seconds over the limit and was disqualified.

A broken distributor drive put Juhan’s Porsche out; he’d been carrying a spare gear in his pocket for several days but decided to throw it away the morning of the last leg. Lippmann also had a breakdown, so that left just two cars running at the finish: Herrarte’s 550 and Segura’s 356S, class winner and runner-up. The winner’s overall time was 23 hours, 43 minutes.

Herrarte, a Guatemalan coffee grower and amateur road racer who almost gave up the race in Mexico City because of exhaustion, took top money of 30,000 pesos. Segura, an Argentinean architect living in Houston, netted 20,000 pesos for second.

It was ironic that the premier race for small sports cars ended in this manner.

Intensely prepared factory entries, with world-class drivers, turned out to be not as reliable as cars in private hands (although the privateers probably put less stress on

their machinery). Clearly, the Carrera Panamericana course was unusually grueling.

The winning Porsche—a Spyder, fitted with a roof (serial number 550-02)—later ran in a sports car race at Puebla and a 1,000-km race in Argentina, then was retired to a place of honor at the Herrarte family home, where it still remains.

Fernando Segura’s second-place 356 was the stuff by which Porsche made its legends. Segura bought it in New York, drove it to Mexico and raced it with no more than a tune-up.

In 1952, only one of two Porsche entries had finished; 1953 saw only two of 10 at the checkered flag. While they had won their class, it wasn’t necessarily cause for celebration in Stuttgart.

Porsche comes of age—1954 Carerra Panamericana V

After the less-than-perfect victory in 1953, Porsche made careful preparations for Carrera V that would ensure its cars’ lasting reliability. Leading the way was the new four-cam engine that produced 110 DIN hp (132 SAE), and already had class wins at Le Mans, Mille Miglia and Silverstone to its credit. But even those credentials wouldn’t guarantee a win in Mexico.

The Borgward RS55 posed a threat to Porsche in the 1954 race until an accident south of Mexico City sidelined it.

Under the sponsorship banner of Fletcher Aviation, Hans Herrmann would drive the Spyder (550-04) that Karl Kling had retired in Carrera IV. Based in Pasadena, Calif., the company manufactured Porsche industrial engines under license from the Stuttgart automaker. Fletcher would also supply a 190-mph, single-engine Navion aircraft; pilot-journalist-photographer Don Downie would fly the plane to provide support for the race team.

Jaroslav Juhan and Segura entered two new Spyders, 550-05 and 06. During the preceding 12 months, Juhan had sold the 550-01 to Salvador Lopez-Chavez with its original pushrod engine, and Lopez-Chavez entered it under the sponsorship of his company, the largest shoe manufacturer in Mexico. In addition, three 356 coupes backed up the team, including one driven by Jacqueline Evans de Lopez, who had purchased the one driven the previous year by Joaquin del Castillo.

Rounding out small sports were the OSCAs of Louis Chiron, Roberto Mieres and Manfredo Lippmann. The MT4-1500s were proven giant killers. An OSCA owned by Briggs Cunningham and driven by Stirling Moss had won the Sebring 12-Hour race earlier that year, three laps over a Lancia, and had topped the Index of Performance. In addition, three more OSCAs came in fourth, fifth and eighth in that race, so the make had to be considered a serious contender. Its 1.5-liter twin-cam four-cylinder engine produced 120 hp at 6,300 rpm, and with their 1,280-lb weight, the Spyder could exceed 120 mph.

The Borgward RS 55s of Karl Bechem and Franz Hammenick posed a threat as well. The Hansa-derived 1500cc pushrod engine had been replaced by a new power plant with Bosch direct fuel injection. It was rated at 115 hp and equipped with a five-speed transmission.

The victorious Porsche team, after the finish at Juarez in 1954, with the 550s of Hans Herrman and Jaroslav Juhan.

Another barely break-even pot of 175,000 pesos ($14,000) was set aside for the purse in the small sports car class. After the 1953 race, organizers realized just how fast these little racers were; the group had been moved from its former starting position behind the big stocks to a more judicious spot following the big sports cars. Lopez-Chavez led the starting field from Tuxtla.

Porsche—which was more worried about the OSCAs than the Borgwards—had underestimated the competition. Bechem’s RS 55 beat Juhan’s Porsche to Oaxaca, both hot on the heels of the leading Ferraris of Hill and Maglioli. Bechem had bested Kling’s 1953 class time by seven minutes. Segura, who finished sixth, hit a dog as he crossed the finish line and damaged his 550. Herrmann lost time changing two Dunlop tires by himself, and drove the last 45 miles with one treadless tire. Unlike stock category cars, both sports categories had unlimited time between legs to make repairs, and most took advantage of the time after the grueling opening leg.

The second day, Bechem kept Borgward’s hopes alive by winning leg two from Oaxaca to Puebla and increased his race lead over Juhan to more than seven minutes. Herrmann began working to close the 26-minute gap between him and the leader, as he advanced from fifth to third in class.

By the time the race got to Puebla, Bechem’s teammate, Hammernick, had flipped his Borgward and suffered a broken shoulder, and Lippmann’s OSCA was out. The field had already shrunk to nine.

The comparatively short downhill run of 81 miles into Mexico City was duck soup for the Ferraris, but the class act was Chiron; his OSCA finished just three minutes behind the overall leg winner, Ferrari driver Phil Hill. Chiron had eclipsed the light sports record by nearly nine minutes and stood fourth in class, sixth in overall time.

As a bonus to Porsche’s 1954 victory, seven Volkswagens with sealed engines finished the race without a single breakdown, averaging over 60 mph.

Bechem still led small sports, despite an accident that demolished his left front fender, but Juhan chopped the space between them to 90 seconds. Herrmann, still third in class, now trailed Juhan by 19 minutes, which meant he had gained seven minutes on the short leg. Mieres’ OSCA dropped out with engine problems.

On leg four between Mexico City and Leon, the three-way rivalry suddenly became an intra-race contest between the Porsches of Juhan and Herrmann, when Bechem spun out and crashed the surviving Borgward. To add insult to injury, two following cars duplicated the accident, hampering aid for the injured driver and fatally injuring a Mexican soldier guarding the course.

Chiron in the OSCA was now Porsche’s only threat. The class had deteriorated to seven cars, and six of them were Porsches. Herrmann won the leg and moved to second for the race behind Juhan, whose lead had dwindled to 12 minutes. Chiron was third overall and Segura fourth.

The race tightened up on leg five as Herrmann took leg honors for the second time in one day, narrowing Juhan’s overall lead to slightly more than eight minutes. Juhan’s Porsche had slowed down with a seized valve, and Herrmann chopped four more minutes off the lead in winning the leg. Otto Becker Estrada was last in the class, with an accumulated time four hours back of the leader.

An exhausted Segura passed the wheel of his 550 to mechanic Herbert Linge as Herrmann won the lap from Durango to Parral and had the lead Porsche in his sights. Juhan and Hermann were still third and fourth overall, behind the Ferraris by 90 minutes, but ahead of the rest of the big sports and all of the stock cars.

On leg seven, Hermann moved to within 23 seconds of the leader. In consistent form, he won the leg in record-breaking time, averaging 121 mph. If he continued to drive the last leg at the rate he’d been charging for the last 1,000 miles, a victory for him would be ensured, but Porsche’s racing director, Huschke von Hanstein, called on the drivers to avoid a useless duel that could send the 1-2 victory up in smoke and give Chiron’s OSCA a chance to score. It was sound advice, especially since the lead cars’ engines were beginning to fade.

“19 Hours,” by Dave Kurz, portrays the Spyder that won the small sports car class in 1955, driven by Hans Herrmann.

As the largest crowd in Carrera history watched the finish at Juarez, in person and on television, the Ferraris of Maglioli and Hill flashed across the finish at 140 mph, followed by the Ferraris of Luigi Chinetti and Franco Cornacchia and the homemade racer of hot rodder Ak Miller. Then came the silver cars of Herrmann, Segura and Juhan.

Herrmann had picked up nearly a minute on Juhan on the last leg and won the class by 36 seconds—a narrow margin after 19 and a half hours of racing the length of the country! His last lap average speed was 116 mph. Chiron finished third, followed by Segura and Linge.

Porsche had lived up to management’s expectations that year in Mexico. Its reputation for reliability was beginning to be heard. It had come of age in endurance racing.

The German marque knew it had finally earned its reputation. A little more than a year later, they announced the 356A—the Carrera.

Daryl Murphy writes for several national and international aviation magazines and has published six aircraft and automobile books. His “Carrera Panamericana: History of the Mexican Road Race 1950-54” is considered the definitive work on the race. The author can be contacted at darylmurphy@sbcglobal.net.

Carrera Panamericana Mexico – Part 1