By Robert Louis DalColletto,

We’re losing our World War II veterans at an alarming rate of roughly a thousand a day, so it won’t be long before many of their stories will go untold. One story is about a unique pair of heroes, Howard and Clinton Burdick, father and son aces.

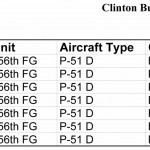

In Dodo, his P-51D Mustang, Clinton DeWitt Burdick flew over 50 combat missions, logged 300 hours and scored five and a half victories.

In a rare interview, Clinton Burdick recently described how he and his father became aces, from flight training to dogfights, and the resulting journey from teenage Brooklyn boys to decorated war heroes. Howard Burdick served in World War I, while his son served in World War II. Although these were two very different wars and two very different men, the traits they shared were remarkably similar. Those traits, including aggressiveness and tenacity, were integral to their success in the air. Although friendly and outgoing men while on land, they were transformed when they took flight.

Ace in training

Now 81, Burdick recalled how his father influenced him during World War II.

“My father told me, ‘Sign up and tell them what you want to do, and they’ll do their best to accommodate you. Otherwise (if you wait to be drafted), you’re just a body, and they have empty spaces. Tell them what you want. Don’t let them decide for you,'” he recalled.

Burdick, raised in Brooklyn, N.Y., followed his father’s advice and enlisted on July 26, 1942, his eighteenth birthday.

“We had pride in what we were doing,” he said with conviction. “We had to stop all that anti-Semitism and ‘land grabbing’ from the French. The Germans invaded France and we were taking it back. My mother didn’t want me to go. But my parents were both very proud of me.”

So, instead of studying aeronautical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he was already accepted, young Clinton Burdick followed in the footsteps of his ace father, and chose to serve his country as a pilot. But he had many hurdles to cross before ever getting to combat. First, he enrolled at Syracuse University.

“It was a preliminary filtering system, because everybody wanted to be a pilot,” he said. “They’d test your academic ability, then take you up in a Piper Cub and do some maneuvers, to see if it bothered you. That eliminated 20 percent of the guys right there.”

Although Burdick tells his story with a no-nonsense attitude and focuses on technical accuracy, he occasionally shows a flare for humor. He wants you to learn, but he wants you to laugh.

“Basic training was near Fort Worth, Texas, where we flew BT-13s,” he said. “Now, on the BT-13, in order to lower the flaps for landing, you had to manually lower it by cranking a handle. One time, I forgot to lower the flaps. It was no big deal; I just came in a lot faster. But the instructor told me, ‘I want you to sit in there and lower and raise those flaps 50 times.’ It took me over two hours; I was exhausted. I never forgot to lower the flaps again.”

Burdick then moved to advanced training, where he trained on the AT-6.

“In advanced training, you did two things, ground strafing (attacking from a low flying aircraft) and aerial combat,” he recollected. “After graduating, I went to gunnery school (as an officer) on Matagorda Island, off the coast of Texas, in the Gulf of Mexico. There, you flew the P-40, with twice the horsepower as the AT-6.”

It was important that the pilots could hit a target.

“They had us fire on a round target, towed on a cable by an airplane,” he said. “They gave you a hundred rounds, dipped in paint. Everyone had a different color. You had to hit the target five or more times, which wasn’t easy. Thirty to 40 percent of the guys didn’t get five hits. They went on to bomber school.”

At that time, the Air Force was transitioning from the P-40s to P-47s and P-38s, and eventually to P-51s. Burdick was transferred to Dover, Del., and flew P-47s in transition flying, combat and formation flying, wingman-flight leader protection systems and low level navigation. He said the difference between a P-40 and a P-47 was like night and day.

“The P-40 was a cantankerous airplane that had a lot of problems,” he said. “The prop had a pitch selection system of its own, sometimes different on different blades, which had a tendency to make it vibrate a lot. In Dover, we did low level navigation in a P-47. One day, I was flying low, 20 feet, when my engine quit. I tried the ignition—click, click; that wasn’t it. So I started cranking the wobble pump (to get fuel to the engine) and it started up. In the meantime, I’d taken eight feet off the top of the trees. When I got back, the crew chief looked under the plane and said, ‘I see you’ve been flying a little bit low.'”

Fuel management was something he never again failed to appreciate. In October 1944, Second Lieutenant Burdick joined the 361st Fighter Squadron, 356th Fighter Group, 8th Air Force, at Martlesham Heath, England. Then came his unforgettable, and somewhat amusing, first combat mission.

“Tail End Charlie”

On Nov. 6, 1944, Burdick was positioned as the last plane in formation.

“We were still flying P-47s then,” he said. “It was my first mission, so I was ‘Tail End Charlie,’ flying on the outside. I was just supposed to shut up and pay attention. We crossed the Channel toward the target, somewhere in the middle of Germany. As we crossed into France, my engine quit. I was losing altitude. I tried the ignition, but that wasn’t it. I tried the turbo supercharger. At about 11,000 feet, the engine roared up and ran like a clock. I figured I’d catch up with the squadron, but at 14,000 feet, it quit again.”

Knowing he had a plane that would fly below 14,000 feet, but not above, Burdick figured he’d “cut the course,” meet the bombers on the way out and follow them back to England.

“After an hour, I was idling over Amsterdam, when I realized the squadron had changed plans and wasn’t coming back to England on the same course,” he said. “I decided to head back. Later, the German gunners on the Parisian Island started shooting at me. But I kept going, over the North Sea. It was getting dark. Do you know what a ‘black out’ is? It really is a ‘black out.’ There were no lights on the whole damn English island, and no way to distinguish a landmark. I knew if I didn’t find a place to land, the only alternative would be to bail out. I flew south until, luckily, I saw the moon reflecting on a long straight thing.”

Fortunately, for Burdick, it was a wet runway.

“After I landed, I slid the canopy back. This British sergeant in a jeep pointed a machine gun at me and said, ‘Keep going, sir,’ and led me off the runway,” he recalled. “Still pointing his machine gun at me, he said, ‘Get out of the cockpit, sir. Who are you?’ I said, ‘I’m an American!’ He lowered his gun and said, ‘Oh, God.’ The next morning, they radioed my squadron leader. He said, ‘Oh, we wondered where he was.’ That’s when we converted to P-51s. They scrapped my P-47 and said, ‘The hell with it.'”

That squadron leader was Donald J. Strait. A captain at the time, he would eventually be an ace with a total of 13 and a half victories. He claimed three victories in P-47s, and later scored another 10 and a half in P-51s. His total made him the leader in victories in the 356th FG. One of the original 361st FS pilots, Strait flew 122 combat missions, which included D-Day operations, in two combat tours. He later commanded the 108th Tactical Wing in Korea, flying F-86, F-84 and F-105 jets. He also served on active duty in the Cuban missile crisis and Vietnam. Strait retired from the Air Force in 1978 with the rank of major general.

Don Strait’s wingman

Burdick described Strait as very aggressive. He insisted his pilots know everything about their planes.

“He wanted you to observe the crew chief and the mechanics working on your plane,” he said. “He was very interested in maximizing your chance of survival. A lot of guys resented spending time in the shop. But you really got to know the plane that was assigned to you.”

Burdick said Strait was “an outstanding commanding officer and an exceptional, technically oriented first class pilot.”

“It was a pleasure to fly with him,” he said. “We still talk to each other. He’s a hell of a guy.”

Recently, the likeable and vastly experienced Strait, in a confident and earnest voice, reiterated the importance of spending time with your plane and crew chief.

“Get to know your crew chief, see how’s he’s doing,” said Strait. “Be maintenance conscious. It’s important to understand and know your planes, because that’s what’s going to get you home someday.”

Strait remembered his impression of the 19-year-old Burdick.

“I always liked his personality,” he said. “He seemed to have a very aggressive, professional spirit about flying airplanes. He flew my wing a number of times. Whenever he had a chance to shoot at airplanes, he was usually successful. I was always impressed with him, because he really paid attention to what he was doing. He gave flight operations a hell of a lot of thought. He’s always been dynamic in his interests and activities.”

While Strait was scoring victories in his P-51D, the Jersey Jerk, Burdick scored his first victory, on Nov. 25, 1944, in his Mustang, Dodo.

“He destroyed a Focke-Wulf 190,” Strait said of Burdick’s first victory, while looking over the actual mission report from that day. “The location was Zwickau, southeast of Namur. It was a bomber support mission, strafing the Zwickau airfield. Clint’s victory was a ground claim (enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground).”

Burdick scored another two victories on Dec. 5, 1944.

“He shot down two Focke-Wulf 190s in the Berlin area,” Strait said. “We were escorting bombers, and as we came off the target, the bombers made a turn to the left, to exit. We spotted more than 40 enemy aircraft, and we immediately attacked. Clint had one victory and one damaged that day. That was the day I became an ace, with my fifth and sixth victories.”

Searching through mission reports, Strait discovered Burdick’s most productive day. He said that on Jan. 14, 1945, they ran into 15 to 20 enemy aircraft, southwest of Dumar Lake.

“That was a prominent navigation mark, west of Berlin,” he said. “That day, Clint got two Focke-Wulfs and damaged two others.”

Proving himself in combat, exhibiting superb piloting skills, and gaining valuable experience, Burdick moved from wingman, to element leader, to Strait’s wingman. Looking at the back of his left hand, Burdick described the concept of the “finger four element”: the middle finger is the flight leader, the index finger is his wingman, the ring finger is the second element leader, and his wingman is the pinky.

“It’s a protection and attack system that works very well,” Burdick emphasized.

Dogfights, strafing and escorting bombers

Clinton DeWitt Burdick, in Martlesham Heath, England, in 1944, was one of only five aerial aces in the 356th FG.

Burdick proudly reflected that escorting bombers was the primary mission.

“After arriving at the target area, we’d peel off,” he explained. “We weren’t going to go with them to the target; no enemy aircraft were there. The fighting began between antiaircraft and our bombers. The German fighters usually attacked our bombers on the way out, especially the ones that were in trouble or got separated. Our job was to protect the bombers from fighters. So, if we didn’t find any fighters, we’d go strafing.”

According to Burdick, Captain Strait was a “firm believer” in strafing, despite the risk.

“He liked to save two to three gallons in his auxiliary wing tanks, find a German air field, and then go down low and drop them on a hangar,” he recalled. “I’d follow him, fire some tracers and set the fuel on fire. It was high risk and high reward, because they could hear you coming. Usually their armament was too strong, and we’d have to pull out. But when it worked, there’d be horrendous explosions. It was thrilling, nerve-racking and scary. But if it worked, you’d put a hangar, and the whole air field, out of business.”

Strait commented on the damage that could be done.

“Airplanes on the ground, marshalling yards, you could kill trains, locomotives,” he said. “But eventually the Air Force put out a rule that the P-51s couldn’t strafe anymore, because they were losing too many of them. The P-51’s a fragile airplane. The engine is cooled by liquid. If you got a chip in the coolant line and lost your coolant, you’d lose your engine. So the airplane becomes quite vulnerable. It’s not as tough as the P-47. The Thunderbolt was the strafing airplane. The R2800 engine could take a tremendous beating.”

Burdick expressed both an appreciation of the P-51’s abilities and awareness of its limitations.

“It was an excellent airplane in its time,” he said. “Every plane, like a car, has its peculiarities, and you have to know them. The P-51 had six guns instead of eight, and had substantial range. It had a 90-gallon fuel tank behind the cockpit. You had to run it down to half full and then use the wing tank, or the center of gravity was too far to the back, and a high G maneuver would stall the aircraft, with no recovery.”

He explained that better maneuverability was obtained by moving your center of gravity forward.

Burdick went on to fly a total of 53 combat missions during his tour with the 356th FG. His last was on Feb. 20, 1945. With five and a half victories, he was one of only five aces in the 356th. When asked about his thoughts during combat, Burdick pauses.

“I don’t mean this as criticism, but many stories you hear about combat are fiction. They’re fabricated and romanticized,” he said. “When you’re on a mission, you’re so concentrated that nothing else enters your mind. You’re all into details, with no overall concepts. A lead pilot in an element of two has tunnel vision. When he attacks, the wingman moves away from him and above him, looking for someone attacking the lead pilot. You defend him, and that’s all you’re thinking about. I flew a lot of missions; it’s like rice in soup. You can’t tell this mission from that. Combat is absolute chaos. You never know where an attack is coming from. You’re either attacking or defending, and you keep doing that job. There’s temptation for the wingman to get victories, but your job is defending the lead pilot.”

Ace father

Burdick’s grandfather, Clinton DeWitt Burdick, was chairman of the board of the Title Guarantee and Trust Company in N.Y. His son, Howard Burdick was born and raised in Brooklyn.

“They had a few bucks, so life was good,” says Burdick. “My dad was a good-looking guy and liked to have a good time. He didn’t do too well in school and flunked out of college, so he joined the Army in World War I.”

Howard Burdick excelled in numerous flight training schools, including Camp Everman in Fort Worth, Texas; the School of Military Aeronautics, at Ithaca, N.Y.; and the School of Aerial Gunnery in Canada. After a two-week journey on a ship, he joined the 147th Aero Squadron, the 182nd, and finally the 39th Training Squadron of the Royal Air Force in Lincolnshire, England. He encountered several forced landings, as well as problems with the engine and jammed guns. During poor weather conditions, he spent a lot of time practicing stunting and firing hundreds of practice rounds.

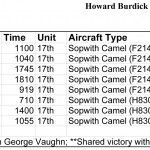

After extensive training, Burdick was assigned to the 17th Pursuit Squadron. He entered combat as part of the British 65th Wing. He joined the squadron on Aug. 17, 1918, and took his first trip “over the lines” on Aug. 21, near Bapame, France.

He flew the Sopwith Camel, an airplane that was difficult to master, but was a maneuverable and agile biplane. It accounted for more aerial victories (1,294) than any other allied aircraft during World War I. However, it was blamed for the deaths of many inexperienced pilots, and many feared its notorious spin characteristics.

Clint Burdick described the Camel as “a big, heavy gyroscope, with a rotating engine and propeller, which could flip into a spin very easily at low speeds.”

“For example, if you pulled up or forward on the stick, it would go left or right, or do a side roll,” he said. “Push the rudder and it doesn’t go left and right; it goes up and down. You have to learn its characteristics.”

While flying the Camel during World War I, 413 pilots died in combat and 385 died from non-combat related causes. Most fatal accidents occurred during takeoff and landing.

According to entries in Burdick’s logbook, the Camel experienced various engine problems: “guns jammed,” “magazine duds,” “engine’s missing” and “dud trigger motors.” Nevertheless, he overcame mechanical challenges and mastered his flying machine. He had eight victories, the highest total for any pilot in the 17th PS.

George Vaughn, one of Burdick’s school friends from Brooklyn, was also in the 17th PS. Vaughn would ultimately become a 13-victory ace, including six victories with the 17th PS. The two men remained good friends after the war. Vaughn was once quoted as saying, “Howard Burdick was by far the most aggressive and perhaps impetuous—a great man to be with in a dogfight.”

His actions on Oct. 14, 1918, best exemplified Burdick’s aggressiveness and intense personality. On that day, his friend, Howard Knotts, a fellow 17th PS pilot, was attempting to strafe a machine gun nest, when ground fire hit his plane. Knotts was able to safely land, but had caught the attention of an enemy pilot as well. After chasing him, Burdick managed to shoot him down, but his rage wouldn’t let him stop there.

“After I killed him, I spent the next ten minutes trying to set his machine on fire, with no results, except using up all my ammunition,” he later recalled.

Although Knotts survived the ordeal, he was captured and spent the remainder of the war in prison camps. He escaped from Mons Prison, but was recaptured and transferred to a prison camp at Soignies. Burdick and Knotts remained friends after the war and would occasionally play golf together.

Burdick flew nearly 200 hours during WWI. Of those, 128 hours were in the notorious Camels, and 102 hours were in combat, in direct pursuit of what he called “the fight.”

Lt. Howard Burdick was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, “for skill and gallantry.” The DFC citation states: “On 25 Oct. (1918), while on an offensive patrol, this officer attacked a formation of five Fokker biplanes over the forest of Mormal and succeeded in shooting down one in flames. On another occasion, he dived on an enemy two-seater, but was in turn attacked by two Fokkers, one of which he succeeded in shooting down in flames. Later, he attacked three enemy aircraft that were attacking one of our machines and shot down one that dived straight into the ground and crashed. This officer has now destroyed five EA (three in flames) and has at all times displayed the greatest gallantry, skill and disregard of danger.”

Clint Burdick said his father’s demeanor was different in the air and on the ground.

“On the ground, he was calm, cool, collected,” he said. “In the air, he was very aggressive.”

The Burdicks never really shared many war stories.

“My father and I might have said a few anecdotes here and there, but that was it,” Clint Burdick said. “We didn’t do a lot of chatting about the war. World War One was a messy war. People really suffered. In trench warfare, the lines didn’t move much. And the living conditions were terrible. Neither side made any progress.”

After WWII

Clint Burdick graduated from MIT, with a bachelor’s in aeronautical engineering, in 1950. When he was 25, his parents divorced. That was a difficult change for him.

“My mother, Katherine Page, was very capable and self sufficient,” he said with pride and certainty. “She knew what she was doing. She was a wonderful woman.”

After moving to California, Howard Burdick remarried, and then settled in Bel Air. He and his son didn’t speak for several years. Then, in 1963, Clint Burdick moved his family to sunny Los Angeles, near his father.

“It wasn’t long before I reconciled with my father,” he said, “We didn’t let our conflicts interfere.”

Howard Burdick died in Los Angeles on Jan. 20, 1975, at the age of 84.

Ace advice

Clint Burdick articulated his sense of duty.

“We have an obligation, as citizens, to defend our society,” he said. “We have an obligation to our children, our family and our country, before we do what we want to do, before we take pleasure in ourselves.”

He also related his view of life’s work.

“Whatever you do, if you do it only to put bread on the table, you’re not going to be very good at it. You have to enjoy it,” he said. “Otherwise, you should be doing something else.”

Today, Burdick and his wife, Connie, are both active, enjoying sunset walks along the ocean cliffs of Santa Monica, Calif. Burdick enjoys woodworking, gardening and especially playing with his grandchildren, ages 4 and 6.

As a grandparent, devoted husband, loving father and brother, Clint Burdick wears many hats in many honorable roles. But he’s also a living hero, a man who not so long ago, like his father, put his country’s needs before himself and his family. Both Howard and Clint Burdick shared a focused intensity, a skilled aggressiveness in the cockpit that led them to being the only known pair of father and son aces in history. They excelled beyond what was required of them, beyond their fears and limitations, to unconditionally defend the country and the freedoms we cherish every day. They teach us that we discover how strong and capable we really are, by applying focus and composure in the face of extreme adversity.

- **Shared victory with George Vaughn and L. Meyers

- Clint Burdick, in the home of his son, Christopher, in Santa Monica, Calif. (2006).