By Terry Stephens

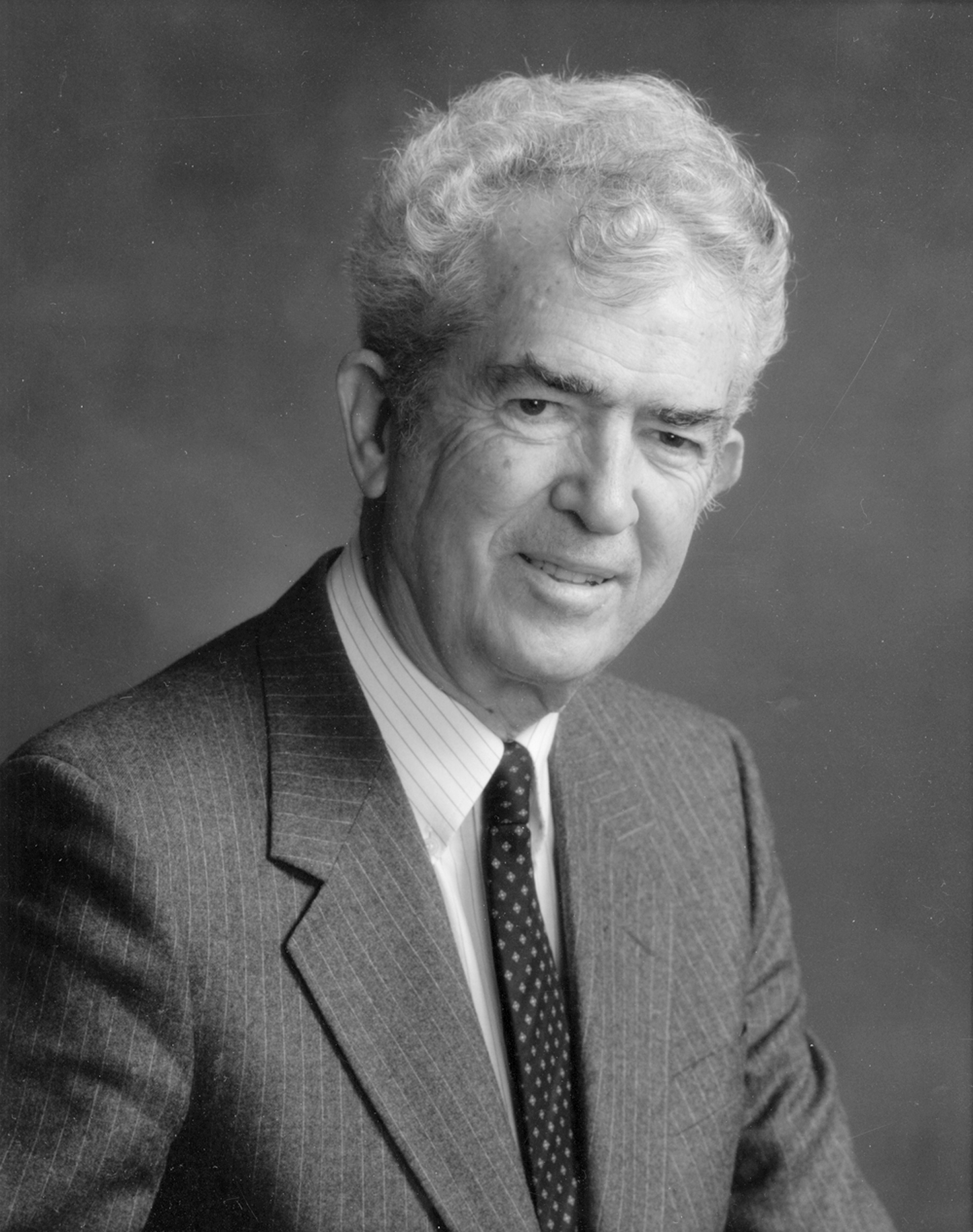

Jack Real’s aviation career included involvement in the development of the SR-71, among many other planes.

Aviation pioneer extraordinaire Jack Real died at 90 in Los Angeles on September 6. He had an impressive career that left a far-reaching impact on America’s military and commercial development, as well as on people’s lives–particularly his longtime friend, filmmaker, aviator and eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes.

Real, who died of heart failure, had suffered from Parkinson’s disease and had been in the Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills for nearly a year, according to Betty O’Connor, his longtime companion.

“He was such a special man and had an influential role in the aviation industry,” said O’Conner, a former executive administrative assistant to Real at Lockheed. “He was a very kind, gentle man, but firm.”

Real had a passion for aviation since his childhood. During his lifetime, his intellect and intuitive engineering skills helped to develop the Apache helicopter, the SR-71 Blackbird and other aircraft during his years working at Lockheed’s famous Skunk Works with famed aircraft developer Kelly Johnson.

He was the retired president and CEO, as well as a director of McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Co., formerly Hughes Helicopters. He served as vice president at Lockheed and as senior vice president of aviation for the Howard Hughes Corp., now owned by General Motors. Among his other prominent aviation roles during his lifetime, Real also was a director emeritus on the board of the Aero Club of Southern California and a member of the SpaceVest Advisory Board, a venture capital firm focused on technology industries.

In 1983, under Real’s leadership, Hughes Helicopters received the Robert J. Collier Trophy, American aviation’s highest aeronautics achievement honor for his role in developing the AH-64 Apache helicopter. He shared the award with Secretary of the Army Jack Marsh.

“It was an honor to work with Jack Real. Not only was he an aviation legend, but he was also a superb businessman, brilliant engineer and friend,” said Tim Wahlberg, chairman of Evergreen International Aviation, Inc.

Wahlberg said Real was essential in assisting Evergreen in creating a home for the “Spruce Goose,” Hughes’ famous eight-engine flying boat. Real served as a director of the Evergreen Aviation Museum, in McMinnville, Ore., for 15 years (until his death). Real is also featured in the Oregon Aviation Hall of Honor at the museum for his outstanding contributions to the field of aviation.

“Jack was an inspiration to youth as well as industry executives and had an amazing impact on aviation,” said Wahlberg.

Jack Garrett Real was born in Baraga, Mich., on May 31, 1915. He graduated from Calumet High School in 1933, earned his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now Michigan Technological University) in 1937. Three decades later, from 1964 to 1965, he attended the University of South California School of Business.

First hired by Lockheed Aircraft Co. as a project engineer, Real moved to California in 1939, in the depths of the Great Depression. Less than a year later he was promoted to senior design engineer on the Model 18 Lodestar program. That move led to designing, developing and testing many of the company’s aircraft projects from the B-14 Hudson bomber and the XH-51, to the Lockheed Constellation, model 286 and 475 helicopters and then the Cheyenne helicopter.

Real was loaned to Pan American Airways for more than a year in 1943 to learn about commercial aircraft development. He served as a flight engineer for Pan Am on the South American and African routes.

Back at Lockheed, he was assigned to work with aviation pioneer Kelly Johnson, and became division engineer for all flight test activities in 1957, and then chief of engineering flight test in 1960. Two years later, his career advanced again with a promotion to chief engineer of research, development and testing. During 1964, he concentrated on the SR-71 Blackbird development with Johnson at the Skunk Works and worked on aircraft testing projects at Southern Nevada’s mysterious Area 51.

By 1965, he was vice president and general manager for the AH-56A Cheyenne helicopter development and by 1968 Lockheed had made him responsible for all of the company’s rotary wing aircraft programs. As fascinating as his involvement in major Lockheed aircraft development and testing program was, it was his close 20-year relationship with Howard Hughes that captures people’s attention. The friendship reportedly grew from their mutual love of airplanes.

Real met Hughes while working at Lockheed. They became so close that from 1957 to 1976, the year Hughes died at 70, Real was his friend, confidant and personal advisor. Hughes appointed Real as senior vice president of aviation for the Howard Hughes Corp., formerly Hughes Tool Co., in 1971. The two men lived together and traveled abroad from 1972 to 1976.

After Hughes’ death, Real became president of the troubled Hughes Helicopters, accomplishing over four years one of business history’s most impressive corporate turn-around efforts. While heading the company, he also guided the development of the AH-64 Apache program for the military. The program was so successful that in 1984 he oversaw the sale of Hughes Helicopters to McDonnell Douglas Helicopters and became president and CEO of that company until his retirement in 1987.

“Jack’s contributions and innovative designs helped pave the way for many modern aerospace developments,” said Nissen Davis, president of the Southern California Aeronautic Association. “He was a giant in our industry and will surely be missed.”

The SCAA launched a campaign to save the Hughes “Flying Boat” from destruction, establishing a public display of the boat alongside the Queen Mary ocean liner in Long Beach, Calif. When that facility closed in 1992, Real and the SCAA worked to arrange moving the giant plane to the new Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville for display.

From 1995 to 2001, Real was the museum’s president, overseeing the construction of the facility and the aircraft’s restoration and reassembly. He became chairman emeritus of the board of trustees for the museum in 2001, as well as for the affiliated Capt. Michael King Smith Educational Institute, named for a deceased local aviator.

After retiring, Real wrote “The Asylum of Howard Hughes,” the story of his long-time relationship with Hughes. It was published in 2003 when he was 88. The book told the truth behind rumors and exaggerations that developed around the reclusive billionaire. In the foreword of the book, Hughes’ first cousin and the administrator of his estate, William Lummis, wrote that “Jack Real was Howard Hughes’ last best friend.”

After his death, one of Hughes’ bodyguards, Gordi Margulis, was quoted as saying that Real and Hughes often spent hours on the telephone talking about aviation. He said, “Jack was a really great guy who cared about Howard and did everything he could to help him.”

During his life, Real was affiliated with the Association of the United States Army, Army Aviation Association of America, and the National Aerospace Council of the Society of Automotive Engineers. He served as a director at large for the American Helicopter Society and American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. He also served on the executive board of the Boy Scouts of America and as a director with the California State University System, Davey Industries, Engineering School Board of Overseers of the University of Pennsylvania, Evergreen International Aviation, Engineering School of Loyola University, Hughes Airwest Airline and Midway Airline.

Aviation may have dominated his life, but he had another lifelong dedication, which was to scouting. Along with President Gerald R. Ford, Bob Hope and General Jimmy Doolittle, in 1983, Real became only the fourth person to receive the prestigious Americanism Award, which is “given to individuals of national stature who have made outstanding contributions to their community and profession.”

In addition to the Collier Trophy and the Boy Scouts of America’s Americanism Award, he received numerous awards and honors over his career. They included the Helicopter Association International’s Lifetime Member Award (2005); Distinguished Alumni Award, Calumet High School, Calumet, Mich. (2004); Oregon Aviation Hall of Honor (2003); The Chuck Yeager Award (1996); The Howard Hughes Memorial Award (1996); Pioneers In Aviation’s Flight Path award, Los Angeles International Airport (1996); Michigan Technological University’s Distinguished Alumnus Award (1995) and Elder Statesman of Aviation and National Aeronautical Association (1989). He received honorary doctorate degrees from Northrop University (1985), the Aeronautical Science Selma College (1983) and Michigan Technological University (1968).

“He had a gift for communicating and relating to everyone regardless of their position,” Tim Wahlberg said. “I respected Jack entirely. He was a true gentleman and a gifted engineer. The aviation industry will miss him; we will all miss him.”