By Lance Gurwell

In 1975, James Lawrence (far left) used the stage name of James Coleman to costar in the number one hit show “S.W.A.T.” as sharpshooter T.J. McCabe.

New York photographer James C. Lawrence has a stock library of tens of thousands of pictures of airplanes. Some are flying above the red rock canyons of Utah, others are over the highest peaks of the Rockies, and still others are air-to-air photographs of planes with Manhattan as a backdrop—no mean feat in itself, given security measures since 9-11.

Lawrence is a regular contributor to Plane and Pilot, Pilot Journal and Outdoor Photographer. But even more than airplanes, he loves the sheer romance and beauty of flight itself.

He began experimenting with ways to apply the creative filters included with programs such as Photoshop. Soon enough, he found he could apply painterly qualities to selected areas—or entire photographs. Imagine Renoir or Monet painting a picture of a World War II P-51 fighter landing at sunset, or Van Gogh and his palette knife smearing the image of a private jet flying low over a field of flowers. Pick a photo, click a filter—or a dozen!—and, to steal a phrase from famous television cook Emeril, bam, the photo looks painterly!

“The French Impressionist period of painting remains my favorite, the one that gets my heart pumping,” Lawrence said. “I love in particular the work of Van Gogh, Monet and Gauguin, the Fauvists who came later, and the great illustrator N.C. Wyeth.”

It’s not that Lawrence needs to perform computer surgery to his aviation images to make them stand out. They’re regularly published and sell well just as they are. In fact, Lawrence said he’s especially careful about his efforts because “it’s tricky with airplanes.”

“It quickly looks like you’re messing around just to be messing around,” he said. “I’m not out to be cute. I want to turn people on; not just airplane people, but anyone, with the glory and majesty of flight. I tend to favor a soft Renoir-like, or Monet-like texture, rather than the obviously techy, digital manipulations such as pasting things in that weren’t there, or changing certain areas to black and white or some unreal color like you see in magazine ads and such.”

Lawrence said he’s not as interested in trendy, flashy advertising-like art as he is in “beauty, pure and simple.”

“Of course, using the computer isn’t as simple as it sounds,” Lawrence said. “There’s a great deal of experimenting, visualizing and reworking involved. I want to make a photo beautiful—as evocative of the mystique of flight as I possibly can. Flight is still a miracle, and when I work with these photos, the sense of the miracle courses through me.”

Lawrence’s interest in flying started at an early age; his photographic skills were acquired along the way. His biological father was a bomber pilot in World War II. However, his parents divorced when he was young, and his mother remarried a professional baseball player.

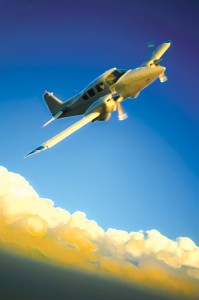

Start with a mediocre scan from a decent but flatly lit slide; open the digital file in Photoshop; stir in a little imagination and a lot of color saturation, filter application to specific areas, and more color, and voila’! The romance of aviation.

By high school, Lawrence was determined to become an astronaut. On his second attempt, he earned an appointment to the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. He headed to the academy in 1963, but found the regimentation wasn’t to his liking.

“I quickly found out it wasn’t the romantic experience I naively assumed it would be,” Lawrence said. “I lasted there two years; the category on my exit papers was ‘lost his motivation,’ and I certainly had!”

While an Air Force career didn’t work out, Lawrence retains respect for the academy experience.

“I’ve never lost the value of learning how much I could accomplish every single day,” he said. “But the training was relentless.”

Lawrence said the rigid position of attention required of cadets—shoulder blades almost touching—caused inflammation in his shoulders and neck to the point where he couldn’t raise his arms above his head.

“I could barely salute,” he said.

And as a cadet, if you’re not standing at attention, you’re probably saluting—or doing pushups. About the same time he was considering quitting the academy, he and some cadet friends saw the movie “Fail-Safe,” in which the U.S. accidentally drops nuclear bombs on Moscow. Hoping to prevent the start of World War III, the American president then orders a U.S. bomber to nuke New York.

It was chilling, all too plausible, and utterly sobering,” Lawrence said. “I thought, ‘I don’t want to do this; this isn’t why I got into the Air Force.’ I’d wanted to go to flight school and be a fighter jock, right? But not everybody gets to fly fighters; some get bombers or transports. When I realized I might be flying a bomber some day, poised to kill millions of people…well, that was the beginning of the end of my academy career.”

Lawrence resigned his appointment and headed back home to Los Angeles. He was soon enrolled at Cal State Long Beach and decided to try acting. He co-starred in a low-budget bicycle racing film called “Slipstream” for fellow college student Steven Spielberg.

He dropped out of school in 1967, after appearing in more than a dozen plays. He acted in repertory theater for seven years, most notably for 19 productions with the Tony award-winning South Coast Repertory Theatre. But by 1973, he’d had enough of L.A.

“I was tired of being broke, tired of being creative and never getting anywhere, and in truth, I just wanted other experiences,” he said.

He and his wife moved to Eugene, Ore. There, Lawrence co-owned an Arabian restaurant named Ali Baba’s, and built geodesic domes. In 1973, he learned to fly his own hang-glider on the dunes of Oregon’s blustery seacoast. At the time, he had no way of knowing how important those first glider flights would be to his career.

“There were no two-seaters, so you pretty much had to teach yourself how to fly,” he said. “You’d trudge it up to the top of a windy dune, and try to keep from blowing over the back side! You’d take these little hops, and pretty quickly you learned the basics of control.

“I remember being parked like a seagull on a pole, hovering a couple hundred feet above a sand dune, just hovering with no forward motion. Those early gliders wouldn’t do much. You could turn them, but they couldn’t penetrate into the wind very well. Top speed was about 25; anything more and you were descending vertically, like an elevator! I fell in love with flying there, and it changed my whole life.”

Lawrence started going to meets and became a decent pilot.

“This was about 1974,” he recalled. “Then I began to miss acting, so I landed a part in a play. And I was hooked again.”

So, it was back to Los Angeles in 1975 for a chance meeting with famed television producer Aaron Spelling. Spelling gave Lawrence his break into mainstream television with a costarring role in the television series “S.W.A.T.,” as the sharpshooter T.J. McCabe (he used the stage name of James Coleman). The show lasted a couple seasons.

In 1980, he costarred with Kirk Douglas and Martin Sheen in the feature film “Final Countdown.” The following year, he appeared in “The High Country” with Timothy Bottoms and Linda Purl, where his hang-gliding skills paid off. He soared for the cameras above the summit of a 12,000-foot peak in the Canadian Rockies. He also acted in other shows, including “Magnum P.I.”, “Barnaby Jones,” “Wonder Woman” and “The Rockford Files.”

Acting roles, however, were too scarce after “S.W.A.T.” to support his new family. Lawrence said he became typecast as a cop or soldier in a period when few police or combat shows were produced.

However, after mastering hang-gliders, he also learned to fly ultralight aircraft. To pay the bills between acting gigs, he was soon competing in flying meets and writing articles about them, as well as shooting pictures, for various aviation publications, including Werner Publishing’s Ultralight Aircraft Magazine.

One of James Lawrence’s regular clients loves to use cultural icons as centerpieces for his monthly magazine editorials. In this one, the client wanted to look like Howdy Doody…but like himself also.

In 1983, Lawrence went through a divorce, and asked Werner Publishing’s CEO Steve Werner if he knew anyone with a steady writing job available. A month later, Werner asked if he’d like to be the editor of Ultralight Aircraft Magazine. Lawrence responded with an immediate, “Hell yes!”

In the wake of ABC’s infamous “20/20” broadcast in 1984 that distorted the extreme danger of ultralights, and nearly sank the ultralight industry overnight, the magazine eventually folded. But the connection with Werner Publishing endured. For eight of the next 15 years, Lawrence was editor or managing editor of several titles, including Outdoor Photographer, Plane & Pilot, Homebuilt Aircraft, Pilot Journal and PC Photo.

Since 1992, he has taken the majority of aviation images for Plane & Pilot and Pilot Journal. Over the years, he’s fine-tuned his photographic and writing skills, while also authoring several tabletop books with some of the world’s greatest photographers, including Frans Lanting, David Muench and Art Wolfe.

Lawrence moved east in 2002 and remarried. He currently makes his living licensing image rights and selling custom archival prints from his extensive stock library of photos and digital illustrations. Additionally, several months a year, he photographs all over North America and Europe for Pilot Journal and Plane & Pilot, from his base in upstate New York. He’s also a regular at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh (22 of the last 24 years) and at Sun ‘n Fun.

As far as his computer techniques, sometimes the work on a single image takes half an hour, sometimes half a day—or more.

“Generally, the time varies a lot depending on the picture and what I want to do with it,” he said. “It’s not so much complexity, as fussing and tweaking to get just the desired effect: not too much, but enough. Then printing, comparing the print with the monitor and often tweaking it more.”

A brilliant blue sky and billowing clouds along with some painterly manipulations in Photoshop gave this already dramatic shot a deeper, more powerful impact.

Asking a photographer to identify his favorite images is almost akin to asking a parent to name a favorite child. But Lawrence was willing to make an observation.

“One of my most popular prints began life as a shot of a beige Cirrus against towering clouds in the Bahamas,” Lawrence said. “The clouds were gray and the airplane was pretty neutral in color. I applied a filter that gives a painterly effect, which I wanted. Then I really pushed the color saturation (with Photoshop on his computer) to bring out the hidden beauty you can’t really even see with the naked eye, but that the film recorded.”

He said that as he worked, he began to discover the gray/blue and white clouds exploding into all kinds of hidden hues.

“It was spectacular,” he said, “Like an N.C. Wyeth effect! But the airplane was way out of whack, much too rich in color. So I ended up working the clouds separately from the airplane.”

Then, he selected small areas of cloud edges and wing and windscreen and control surface edges, to which he applied certain filters repeatedly, and with different settings.

“I was after a particular, ghostly effect that would highlight the edges, but subtly,” he said. “It’s often trial and error throughout, not unlike oil painting, only you start with the image already there and work with the texture and feel of it. In time, you release what’s hidden from the “straight” photograph. Great, great fun. And the more you do, the more you want to do.”

These days, Lawrence mostly shoots with digital cameras, although the computer manipulation processes are similar for film or digital images. Film images must be scanned first before imaging can be done.

To learn more about James Lawrence, and see samples of his work, visit [http://www.skypix7.com].