By Richard Hansen

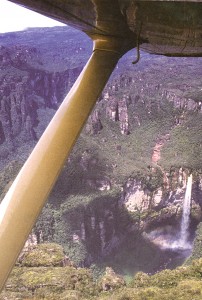

Venezuela’s Angel Falls, rising 3,212 feet, is named after Jimmy Angel, an adventurous American pilot who first saw the falls in 1933, while searching for a “river of gold.”

One of my favorite books is “Natural Wonders of The World,” which shows pictures and descriptions of hundreds of the world’s most outstanding natural wonders, including the highest mountains, glaciers, major lakes and waterfalls. One of those waterfalls is Angel Falls; rising 3,212 feet, it’s the world’s highest waterfall, and one of Venezuela’s most touted tourist attractions.

Angel Falls isn’t named for a heavenly being, as one might think. It was actually named after an adventurous American pilot who first saw the falls in 1933, while searching for a “river of gold.”

Information on the Missouri native wasn’t easy to find, but success was finally achieved through the Missouri Historical Society, who graciously checked their archives and found a Kansas City Times article written Feb. 28, 1967, entitled, “In Death, as in Life, Jimmy Angel Is Legendary.” The society also uncovered a lengthy article entitled “Angel’s Secret,” written by Paul R. Eversole, one of the pilot’s friends. Those historical articles, Internet information, and children’s books about Angel Falls eventually provided enough information for this recap of the fascinating pilot’s adventure-filled life.

Jimmy Angel was born Aug. 1, 1899, in Springfield, Miss. At age 15, he ran away from home, with his father in hot but unsuccessful pursuit. He soon found his way to Canada, where he joined the Canadian Royal Flying Corps, and convinced them to teach him to fly. Seeking to be a part of the Great War, he went to England, and with his considerable flying skill, flew in France, downing several German aircraft and two observation balloons.

The ending of the war saw him in Capetown, South Africa, where he joined a fellow aviator, Joel Ince, and spent time in Sidon, Cambodia and French Indochina, before heading back to London. He then signed a contract with the North China government to fly for a warlord in Kansu Province.

At age 19, Angel was in command of his own “air force” in Northern China at an airfield called Wei-Wei. His “fleet” consisted of five World War I aeroplanes, but only two ever flew. He later said that his airfield in China “bordered the ends of the earth in three directions and faced hell (The Gobi Desert) on the fourth.”

During those months in China, Angel went to Tibet for a change, and excitement. While there, he met a Russian Jew, and the two of them prospected for gold. Soon after, bandits stole all their possessions, but thankfully spared their lives. A couple of months later, back at the China airfield, another group of bandits (of Mongolian descent) totally destroyed the airfield and killed Angel’s partner and others.

His airfield destroyed, Angel blamed himself, and made plans to return to the states, but then was stricken with malaria. The warlord’s crew kindly carried him in a litter to Shanghai’s Rockefeller Clinic. He emerged a skeleton of a man, bitter, but now more determined than ever to live his own kind of life.

When asked about the China experience, he didn’t say much, just, “I flew for a warlord,” or “I dropped homemade bombs on desert bandits.” The more gruesome details of the Wei-Wei come from other sources. But the spark of his Tibetan adventure ignited his lifelong passion to relentlessly search for gold.

Within a few months after leaving China, Angel found his way to Panama. There, he met and old prospector named McCracken, who told him of a “river of gold” in the outback of Venezuela. McCracken said that although he and a former partner had discovered gold in the area, due to the political problems in Venezuela, he had fled to Panama.

Although few believed him, Angel would later tell anyone who would listen how McCracken had led him to a stream in the beautiful high unmapped Gran Sabana Mesa. He said that a waterfall “over a mile high” flowed from the mesa.

In 1921, Angel and McCracken left Venezuela and returned to Panama. Looking for more work, and action, Angel went to Mexico and flew payrolls for two mining companies. Action he got: on one trip, a notorious bandit robbed him, but spared his life. On another occasion, Angel was forced to give a robber lift, but rolled his plane and dumped the unwanted passenger out!

Another time, he and a companion crashed in the Sierra Madre; they were alive, but stranded in this dangerous area. Then, at age 22, he returned to the states. For the next five or six years, Angel and his brothers became rather famous in the Mena, Ark., area, as daredevil barnstorming aviators.

A story that appeared in the Kansas City Times said that in one of her columns, Mary Alice Swaty, of Big Park, Ark., wrote that when she was 10, Angel’s plane was the big attraction at a Mena picnic.

“Forging my way through the crowd, I stood staring in fascination at that flying wonder,” she wrote. “It looked safe enough. The seat was enclosed, sides and top, with poultry net. Then a voice was saying, ‘Wanna sail over Mena?’ ‘Sure,’ I replied, ‘but I have only 50 cents.'”

She recalled that Angel smiled and said, “That’s the exact price of one fare,” before opening the door for an exciting ride.

“Jimmy strapped me in saying, ‘So you won’t fall head first into the wire,'” she recalled. “I saw what he meant when he did barrel rolls, tumbling earthward like a mortally-injured bird. Nothing can compare with Jimmy Angel’s idea of a short spin in his patched-up flying machine.”

On a scorching August day, a beautiful, red-haired wing-walker named Virginia Martin caught his eye. She was adventurous and, like Angel, a vagabond of sorts. In just two weeks, they were married in Coffeyville, Kansas.

Their barnstorming stunts thrilled many. Jimmy Angel also worked as a movie stunt pilot, appearing in Howard Hughes epic “Hell’s Angels,” and also in “Wings.”

In his later twenties, Angel moved to California, and began flying in South America. In April 1928, he and Presho Stevenson took off from Fresno, Calif., on a 25,000-mile journey around Cape Horn and back, financed by Stevenson. Their biplane could go 1,000 miles without refueling, at an average speed of 100 miles per hour with a 100-gallon tank.

In the late 1920s, the Angels established the first feeder airline in Mexico. After years of frustration and hardship, they were well on their way with their first solid financial success.

But Angel never forgot his Venezuelan experience, and his wife knew that sooner or later he would have to return. Then Angel met up with D.H. Curry, a mining engineer prospecting in Mexico for the Santa Ana Mining Company of Tulsa, Okla. Leaving his fledging airline, Angel convinced Curry to hit up his employer for money so that the two of them could go look for gold in Venezuela. The mining company eventually invested $25,000 in the Angel-Curry venture, which Angel promised would yield “nuggets of gold—as big of my fists.”

In 1933, Angel and Curry left on their first of three ventures. On the first trip, they sighted the waterfall that was “at least a mile high,” as Angel noted in his flight log. Towards the end of that year, Angel met up with his wife in Mexico City. He casually mentioned the waterfall, but otherwise considered the trip a total failure. Unable to convince him to leave the area, Virginia left him.

A year or so later, Angel met and married Marie, another flaming redhead. Soon after, in 1935, she accompanied him on his second trip to Venezuela in his search for “El Dorado.” Again, he focused attention on the huge mesa in the Gran Sabana—”the one that didn’t appear on maps”—and therefore, according to many people, couldn’t exist.

In Caracas, by now, Jimmy was well-known as a character of sorts. As for his mile-high waterfall, that was just another tall tale by the crazy North American pilot.

The Angels returned again in 1937, along with explorers Gustavo Heny and Felix Cardona. Heny’s manservant, Miguel Delgado, conceived the elaborate, bold plan to land Angel’s plane, the “El Rio Caroni,” on top of the mesa, next to the “river of gold.” Putting a plane down on top of a mesa with huge crevasses, cliffs, swamps and tangled undergrowth was risky, but critics are wrong when they claim it was a slipshod and ill-conceived undertaking. In fact, it was anything but.

Angel’s obsession was blind to dangers. Certain that gold was up on the top of that “damn mesa,” he said he’d find it if it killed him. Initially somewhat wary of the adventure, Marie gave in when she saw how determined her impetuous husband was to go.

Still, she resolved that nothing would be left to chance. That was good, since details bored Angel, and he lacked the patient art of planning and logistics. It was her meticulous foresight that saved the party from disaster when his plane mired in mud atop the mesa, permanently.

The party of four tried to make radio contact with Captain Cardona at their base camp at the foot of the mesa. When this failed, they set out on the long, arduous trek down the mesa, led by Heny, an expert woodsman. Just such a contingency had been provided for, and they had everything needed for survival. Marie even thought to include her husband’s “Lucky Strike” cigarettes.

After five days spent trying to contact the party by radio, Cardona sent out urgent distress signals for assistance. In Caracas, the lost party became a hot topic. Foreign newspapers picked up the story. If it was true that there was a mesa back there after all, was Angel’s “mile-high waterfall” also real?

When Angel landed his plane on the high plateau near the falls, the international attention was clearly on him ad his crew. Would they make it down the mountain safely? Without radio contact, the anticipation of the world grew each day. After 11 days, the battered and bruised crew emerged. It was the perfect time for Venezuela to name the falls after the man who had first seen it.

Thirty-three years later, Angel’s plane was finally taken down from the plateau, by helicopter. The plane, which has been on prominent display outside the airport at Ciudad Bolivar, is one of Venezuela’s most visited spots.

The last 19 years of Angel’s life saw him searching for the “river of gold” and trying to find the lost cities he had heard about. Jimmy Angel died in Gorgas Hospital in Panama on Dec. 8, 1956, following a landing accident in David, Panama. According to his last wishes, he was cremated and his ashes scattered over Angel Falls.