By Karen Di Piazza

“This is cool. You’ll want it; you’ll need it,” said Joe Clark to the aerospace industry, when pitching Aviation Partners Inc.’s Blended Winglet Performance Enhancement System.

“We believe anything you can do to enhance the value of an aircraft by improving its performance is a wise investment,”says Joe Clark, CEO Aviation Partners, Inc.

An innovative thinker who has surrounded himself with others in that category, Clark is the cofounder and CEO of Aviation Partners, a Seattle-based company that has raised the “wing” of aviation a few notches higher, with new attitudes, altitudes and latitudes.

Because of Clark’s innovative ideas, an all-star aviation dream team, and the right connections with the Boeing Company, API will bring home somewhere around $100 million this year.

“We have the crème d la crème—some of the best minds in aviation—right here,” says Clark.

For starters, Dick Friel, senior vice president of sales and marketing, is a crucial part of the team. His expertise goes back to Lear Jet Industries as former vice president of marketing. His achievements have won him many honors and awards, including the Man of the Year award from the American Marketing Association and selection as one of the Top 10 Men in Business Aviation, by Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine.

In addition, he’s been president of Arctic Development Company, and senior vice president of marketing for a major home improvement chain. Friel, who has known Clark for 30 years, says Clark is known throughout the aviation industry for being a true visionary.

“He’s been instrumental in enhancing the look, performance and bottom line benefits of aircraft,” he said. “He’s totally dedicated to creating something new in the air. And I’m not saying that because I work for him!”

Also on Clark’s team is Louis Gratzer, Ph.D., who is chief of technology and research, and has “a brilliant mind.”

“He was Boeing’s chief of aerodynamics for more than 30 years and was responsible for the aerodynamics of all Boeing commercial airplanes,” Clark said. “Dr. Gratzer participated as a project leader in the design of the America’s Cup winner, Stars and Stripes, and was selected as one of the five finalists for the prestigious Discover Award in Aviation and Aerospace in 1994.”

Gratzer developed and patented the “Blended Winglet.” Winglets have been around since NASA first came up with the concept in the 1960s. However, they protruded straight up with a sharp angle from the wing—unlike Aviation Partner’s blended winglets.

Joe Clark co-founded API in 1991 with Dennis Washington, after Washington, a business tycoon from Montana, asked Clark if he could do something about extending the range of his Gulfstream II business jet. Introducing the GII to blended winglet technology, installed for $520,000 with only about 10 days downtime, reduced the drag by more than seven percent.

After that first Gulfstream, others were equipped with the technology. And, Clark would discuss the technology with Borge Boeskov, at the time vice president of product strategy at Boeing Business Jet, and now former president, as of his retirement in March 2002.

“Our initial conversations were aimed at the 747s,” said Boeskov. “I believed in the blended winglet concept; however, engineers at Boeing didn’t. They knew of Clark’s success with Gulfstream, but they were engineers. With that mentality, they thought, somehow, those wings were ‘different.'”

Then, during the Paris Air Show in 1997, Boeskov approached Clark about putting the blended winglets on the modified version of the next generation 737-700.

“The Paris Air Show is significant because we had just launched the BBJs in 1996,” Boeskov said. “I knew it was time to get Joe’s blended winglets on our 737s.”

However, Boeing engineers, unable to believe that the winglets would improve performance by at least five percent, dug in their heels and refused the concept. Taking matters into their own hands, Clark and Boeskov sealed a deal with a handshake, deciding to form a joint venture, Aviation Partners Boeing. Later they signed a one-page contract.

Boeskov agreed to fund the cost of building a prototype and the testing using BBJ’s budget; Clark would foot the bill of the blended winglet design and would build it.

“The thing I admire most about Joe is that he’s a ‘do-it’ kind of guy,” says Boeskov. “Joe is ‘Lord of the Wings,’ and he calls a spade a spade. He’s not into all the red tape and pony shows that are often required when dealing with engineers who are caught up in company red tape. Joe is the kind of entrepreneur who gets things done. ‘Going for it’ is an understatement. He was ready to get the blended winglet on the BBJ as quickly as possible. So was I.”

However, they needed a 737 on which to test the technology.

“Timing was everything. In order for the blended winglet to become a success, we had to find an aircraft that was instrumented correctly to fit the concept,” explains Boeskov. “We needed an aircraft that had all the data-collecting instruments.”

Hapag-Lloyd was to take delivery of the first 737-800. Boeskov flew to Germany to visit the company, which agreed to the use of the aircraft for the first blended winglet installation/certification, although it meant a delay in delivery.

Instead of five percent, nearly seven-percent reduction in drag was realized, through the winglets, with a height of eight feet, three inches.

Now, as the world’s leading designer and producer of advanced technology winglet systems, API is geared up to transform the productivity and performance of business and commercial aircraft throughout the world.

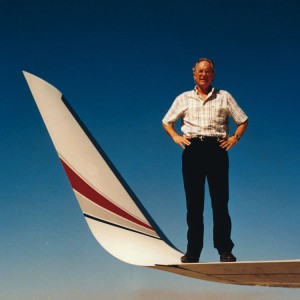

Joe Clark, standing on a GII wing with blended winglets, is chairman of Aviation Partners Boeing Company. He looks forward to putting the technology on the entire Boeing fleet.

To date, more than 100 Gulfstream GIIs have been transformed to IISPs with blended winglets. The company has performance enhanced more than 60 percent of the GII fleet, and GIISP operators are realizing up to 7.3 percent additional range with faster time to climb. In addition, this has improved higher initial cruise altitudes and has boosted handling characteristics throughout all phases of flight.

More than 60 Boeing BBJs and 80 Next Generation 737s are now equipped with blended winglet systems. In addition, Boeing is installing blended winglets on all of their aircraft as standard equipment.

In the universe of Boeing aircraft, Clark has his eye on retrofitting more than 10,500 existing aircraft including the Boeing 737-800, 737-700, and classic 737,757,767 and 747, which he believes will benefit from quiet and environmentally-friendly blended winglets.

But Clark hasn’t caught the attention of everyone. Airbus still uses traditional winglets.

“Airbus’ traditional winglet doesn’t do a thing for you,” said Boeskov.

It’s not a question of “if,” but of “when” companies not yet utilizing blended winglet systems will take the option, says Boeskov.

“The runways in Europe are shorter and more difficult, and the noise problem with jets is an issue,” he said. “So, it’s just a matter of time until they can afford to install the blended winglet.”

Clark agrees and said it’s likely his company will capture 99 percent of Europe’s business.

The icing is that the technology gives aircraft a brand new look. Clay Lacy, founder and CEO of Clay Lacy Aviation, was one of the first Gulfstream II operators to adopt blended winglet technology. With more than 50,000 hours of flight time, he’s operated a blended winglet equipped GIISP for years.

Besides saying that the technology gives a significant benefit in terms of range and fuel margins, Lacy says it also gives an aircraft a much more modern look.

Others on the blended winglet technology bandwagon are Wayne Huizenga, Miami Dolphin team owner who is also a BBJ owner; Charlie Horky, CEO and founder of CLS Transportation, the largest limousine operator in the U.S.; and Men’s Wearhouse CEO George Zimmer, who knows that API really knows how to dress up a plane.

“It gives their corporate jets a sexy look, which is appealing to CEOs,” says Clark. “The blended winglets look so perfect—like they’ve been there all along.”

A “designer plane” look may be important, but the performance speaks for itself.

For example, blended winglets used on a Hawker 800 removes the vortex completely away from the transition area, which reduces overall aerodynamic drag. In addition, using curved blended winglets on the 800 transforms the Hawker into a reliable nonstop coast-to-coast aircraft in most conditions.

The Federal Aviation Administration has certified Boeing 737-700/800 next generation aircraft using the blended winglet technology. The blended winglet will be available as a retrofit for 737 classis series the first quarter of 2003, and will be certified for the Boeing 747-400 in early 2004.

Blended winglets offer a way for airlines to reduce operating expenses, thus raising profits. By using blended winglets, aircraft can fly up to six percent farther, depending upon the missions flown. Engine maintenance costs are reduced because of four percent lower power setting on takeoff. Moreover, it offers improved range/payload when operating out of high and hot airports as well as a 6.5 percent reduction in noise footprint.

It doesn’t make financial sense anymore for airline manufactures to completely redesign aircraft. Nor does it make any sense for engine manufactures to spend hundreds of millions of dollars re-fanning engines to achieve the four to six percent drag reduction. It makes sense using blended winglets for fuel efficiency and range benefits.

Joe Clark’s love of aviation includes this L39 fighter jet, which he has flown and marketed throughout the world.

“It’s a no-brainer,” says Clark. “Blended winglet technology is the most exciting technology in the marketplace; it can enhance the overall performance of any type of transport aircraft. When an airline or cargo operator realizes that a product will save them four to six percent in fuel burn, increase the range of their aircraft and give them a host of other valuable performance benefits, it gets their attention quickly!”

There’s more to a winglet than meets the eye. Something that looks like a “Star-Trek” aircraft may be on the horizon for commercial carriers; the “Spiroid” winglet was tested by Gulfstream and API years ago.

“It’s a tip that loops right round back on itself in a 360-degree spiroid, which can boost range by 10 percent,” says Clark.

Some say these are less attractive and that the corporate client might shy away because of that. Clark doesn’t agree; he thinks they’re very appealing.

Joe Clark

Joe Clark loves the challenges of designing new products for aviation and regularly captures the attention of the world aviation press. Recently named a trustee of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, he was also named Innovator of the Year by Professional Pilot Magazine.

Born in Canada, Clark moved with his American father and Canadian mother to the U.S. three weeks after his birth, and is a naturalized American citizen.

A lifelong resident of Seattle, he attended Lakeside High School, where his father was the first to graduate.

Clark says that while growing up, he was rebellious. He remembers a time when he and friends were egging cars, and he threw one that spattered all over the inside of a car. When the owners of the car came after him, Clark, using crutches due to a skiing accident, was unable to run fast enough to get away.

“They took me back to their house, sat me down, and every minute threw an egg at me–five dozen of them,” he said. “That taught me a lesson.” Besides playing youthful pranks, Clark’s rebellion included stealing a “little bit of booze.”

But Clark’s family served as a stabilizer.

“My mother was very different,” he said. “She went to art school. She was deaf and wore a hearing aide growing up. Luckily, she didn’t hear most of the stuff I said.”

Later, as one of the first to receive an operation where plastic tuning forks were placed in her ears, she went from being totally deaf to perfect hearing overnight.

Clark learned about the “softer” side of the world from his mother.

“She was an affectionate, warm person who sang songs to me as a child,” he said. “Most of all, she was kind to people. She never said a bad word about anyone. She had a motto: ‘Aim for the stars, even if you only hit the chimney pots.’ She made me feel that if I aimed, I’d have a chance of getting there.”

Clark considers his childhood an asset and credits it with giving him worldly insight, which has rubbed off in the way he runs his business today. While growing up, they didn’t have a TV.

“Not until much later anyway,” he said. “I remember the ‘Ricky Nelson’ show was a family event. I was lucky to have had a normal loving family. All of us—my two sisters and brother—ate dinner together each night and we talked.”

Clark described himself as a “goof off” in school who was bored with it. He attended Ridley College, an all-male boarding school in St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada, and says that when he got out of boarding school, he felt like he had gotten out of prison.

“Those Canadians didn’t mess around; you got out of line and they strapped you and all that kind of stuff,” he said.

Later, he attended the University of Washington. He says that when he attended college, he just “wanted to have fun.”

While he may have a “mad passion” now for aviation, while growing up, it didn’t even cross his mind. It did during college.

“I dropped out and started flying,” he said. “A buddy of mine had purchased a P-51 Mustang—surplus of the government. Can you imagine two 19 year-olds flying around? It was cool; we flew everywhere in that Mustang. From that moment, I was hooked.”

It wasn’t long afterward when Clark got his private pilot’s license.

“I had the desire to fly, but no direction or motivation for business,” he said.

When he speaks of business, he tells of his father’s influence in that area. As for his father, Clark says he was his mentor and “a real genius.”

“I don’t think I inherited that,” he said. “Growing up in a wealthy family, his brilliancy was noticed early on. His parents would send him on a private railroad car down to Mazatlan, Mexico. He could read by age four and later he ended up reading a book each day of his life. He stuttered, because his mind worked faster than he could get the words out.”

Besides having a great sense of humor, his father was also “extremely ambitious.”

“At one time, he was CEO of two companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange,” explains Clark. “One of those companies was Cascade Natural Gas, based in Seattle. My father also formed Northern & Central Gas Company, a Canadian based company. Both were natural gas distributors.”

Clark says it’s interesting to reflect back about his father and the influence he had.

Created in response to business jet operators who need to extend range and improve performance,Aviation Partners designed a Blended Winglet Performance Enhancement System for business and commercial aircraft.

“Looking back, I see now that watching my father take a risk in business is the reason I haven’t been afraid of doing it,” he said.

Clark’s father hired him at one of his companies and sent him to the West Indies to live for a year.

“I lived on Montserrat, now gone because of the volcano,” he said.

Clark worked at a real estate development company that was putting in a golf course.

“Then, I started getting the idea of what business was,” he said. “I also dealt with the local natives and sold them cattle herds, which was another part of a subsidiary of my dad’s company.”

Later, Clark was transferred to work at his father’s gas company in Canada, where he sold gas water heaters to businesses. He didn’t like it and returned to Seattle.

“I was really interested in aviation,” he said. “A friend of mine took me to the Reno Air Races in 1964. That’s when I met Clay Lacy. Clay took me for a ride in a Learjet and my life changed at that moment. I knew at that moment I had to find a way to get a Learjet.”

Clark’s father traveled all of the time, as did many people that worked for him, so naturally he thought his father’s company should purchase a Learjet.

“Clay ended up giving my father a demo ride in a Learjet,” Clark said. “We flew from Seattle to Canada, which only took about 50 minutes, compared to a day (by other modes of transportation) back then. Dad was impressed with that and we met with Elroy McCaw (father of Bruce McCaw), who was on the board with Learjet. Bill Lear told me that if I could find a way to buy a Learjet, he’d offer me a dealership in the Pacific Northwest and all of Canada.”

Lacy and Allen Paulson (who later became CEO of Gulfstream) joined Clark in this endeavor, and Jet Air was born, in 1965.

Jet Air was the first Learjet distributorship in the Northwest. His sales territory was Washington, Oregon, Alaska and all of Canada.

In the seventies, Clark worked with Gates Learjet and held the position of vice president of sales for Raisbeck Engineering. In 1981, he teamed with Milt Koult to form Horizon Air. After it became highly successful, the Seattle-based regional airline was sold to Alaska Airlines. During his stint with Horizon, he served as vice president of sales and marketing, oversaw special projects, and later became director.

In 1987, Clark founded Avstar, Inc., a worldwide sales system to market ex-military jet training aircraft to American companies and private individuals alike.

In 1988, with Clay Lacy and Bruce McCaw, he established the Friendship Foundation, which set an around-the-world speed record of 36 hours, 54 minutes and 15 seconds in a Boeing 747SP, on Jan. 28, 1988. The event, publicized via television and print media, raised $530,00 for children’s charities around the world.

At age 61, this wealthy bachelor is doing what he loves to do in life–being around aviation, talking aviation and inventing new ways in which he can help improve the industry that’s been good to him.

“Of course I try to get some golf and skiing in to from time to time,” he laughs.