By Di Freeze

“Joe Clark took his jacket off yesterday and some feathers fell out,” laughed Dick Friel, when speaking about the founder and CEO of Aviation Partners, Inc. and chairman of Aviation Partners Boeing, who has been chosen as the recipient of the 2004 Michael A. Chowdry Aviation Entrepreneur of the Year award, presented by Airport Journals.

Joe Clark, founder and CEO of Aviation Partners, Inc. and chairman of Aviation Partners Boeing, is the recipient of the 2004 Michael A. Chowdry Aviation Entrepreneur of the Year award, presented by Airport Journals.

“Joe has been a friend of mine for over 30 years, but his very best friend is aviation,” he said. “He loves everything about it-flying around the world or in the local area.”

Friel, senior VP of marketing and sales for Aviation Partners, Inc., and senior VP of marketing and communications for Aviation Partners Boeing, said that Clark’s “happiest times are in flight.”

“Seriously, winglet technology is just an extension of his vision about the design, development and creation of innovative plans for planes,” Friel said.

Friel said that Clark’s entrepreneurial spirit, energy and innovative skills are “the hallmark of his leadership and success in the aerospace business.”

“He thrives on challenges to his ideas for performance enhancement and environmental benefits for business and commercial aviation,” he said. “He loves aviation and is dedicated to making it better. It’s exciting to be around Joe because you never know what his flight plans are for the future of Aviation Partners.”

This year’s selection of Joe Clark was not only because of his success in making a dramatic, positive and lasting impact on the industry, but also because of the extraordinary fuel savings and environmental impact created by the efficiencies of Blended Winglet Technology. Clark led the development effort in that technology over 12 years ago. At that time, very few people had any idea of what a huge impact this technology would have on boosting the efficiency, performance and environmental friendliness of business and commercial aviation.

Since developing the patented Blended Winglet in 1991, Aviation Partners, Inc. and Aviation Partners Boeing, a joint venture with The Boeing Company, have changed the economics of flight by dramatically improving wing efficiency and aircraft productivity. The original Blended Winglet, designed for the Gulfstream II business jet, defied all industry predictions by reducing overall aircraft drag, and boosting range, by more than 7 percent. In the past, aircraft have been entirely redesigned or re-engined to achieve such measurable performance increases.

Today, over 500 Boeing 737s are outfitted with Aviation Partners Boeing Blended Winglets, with orders for over 1,200 additional shipsets. Southwest Airlines, Continental Airlines and Alaska Airlines are just a few of the 33 major carriers in the process of upgrading to Blended Winglet Technology. Over 90 Boeing Business Jets are Blended Winglet equipped as standard delivery configuration. Aviation Partners Inc. has successfully performance enhanced over 70 percent of the Gulfstream II fleet and has recently certified a Blended Winglet program for Raytheon Hawker 800 and 800XP business jets.

The average Blended Winglet equipped Boeing 737 saves over 110,000 gallons of jet fuel each year. If all Boeing aircraft were retrofitted with Blended Winglet systems worldwide, fuel savings would be close to two billion gallons each year.

Blended Winglets are markedly larger, and of wider sweep, than the traditionally smaller and angular winglets that can be seen on earlier generation aircraft. Once a business or commercial aircraft is upgraded with this “visible technology,” the benefits are there over the entire economic life of the aircraft. An added bonus of this technology is a significant global environmental impact.

Clark says he loves being involved in a “fun” business. Part of that fun is what people say about his product.

“It’s very unusual to have a product where people come up to you and say, ‘You know you build the coolest stuff,'” he said.

He particularly likes how Alan Mulally, executive vice president of The Boeing Company and president and CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, refers to his product.

“He calls it ‘Way Cool Technology,'” Clark says with a grin.

Headquartered in Seattle, Wash, Aviation Partners, Inc. initially designed a performance enhancement system for the GII wing to explore the possibility of extending the range and improving performance.

“Winglets are a device that can be put on any airplane that will make them more fuel efficient, quieter and put less pollutants in the air,” Clark said. “We can literally put ours on just about any airplane, and usually can substantially improve the performance.”

Clark carried out his vision through a highly experienced “Dream Team” of aerospace professionals consisting primarily of retired Boeing/Lockheed engineers and flight test department heads.

Clark is understandably proud of a speed record he recently set with Clay Lacy in a Hawker 800SP-an airplane that he says now looks like a “baby GV,” because of the Blended Winglets. The two men arrived at the NBAA annual convention en route from Maui.

“What was interesting about that record wasn’t so much the speed,” Clark said. “What we were trying to show is this is not a typical mission that you would do in a Hawker. We’ve so substantially increased the range of the airplane with our latest certified winglets that flying from Maui to Las Vegas is a very comfortable trip.”

Clark recalled that while they were flying over Los Angeles, Lacy turned to him and grinned, saying, “You know, Joe, when we flew the DC-8s from Hawaii to the West Coast, we used to land with an hour and 20 minutes of fuel. We have two hours and 20 minutes of fuel over Los Angeles in the Hawker.”

Two other pilots took the airplane from Van Nuys to Maui.

“That trip was made in six hours and nine minutes,” he said. “They landed with 2,050 pounds of fuel, which is a substantial amount of fuel for the Hawker-an hour, 40 minutes plus. Going over, we had 55 knots of headwind average. Coming back, we had no help from the wind-maybe 10 knots at times. We came back in five hours and 34 minutes; the speed was just under 500 miles an hour. We landed in Las Vegas at about 6:30 at night. It was a great trip. It really showed the ability that the airplane has with this technology.”

Back to the beginning

Joe Clark’s mother was Canadian and his father was American. He was born in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, but wouldn’t be there long.

“I moved to Seattle at the ripe old age of three weeks,” he said.

He grew up in Seattle, attending Lakeside until his tenth year, before heading to eastern Canada to attend a boys’ prep school. Later, he came back to the University of Washington, which he attended for a couple of years, before attending Central Washington State College, in Ellensburg, Wash. While there, he began taking flying lessons.

“A friend of mine, Chuck Lyford, was flying at Mount San Antonio College,” Clark said. “At 19, he bought a P-51, and he took me for a ride in it. That was a big thrill.”

Clark soloed and got his private pilot’s license in 1961.

“I didn’t have a lot of money then; I couldn’t really afford to fly very much,” he said. “I flew Super Cubs and all kinds of airplanes, and loved that stuff, but I was really smitten by the P-51.”

He would also soon fall in love with Lear Jet Industries’ revolutionary new jet, due to a pilot he met at the Reno Air Races in 1964. Clark attended the races with Lyford, who mentioned that he had to meet one of the pilots.

“He’s a great guy,” Lyford told Clark. “He’s a fellow air race pilot, a National Guard pilot, an airline captain-and he has a fabulous airplane.”

Soon after they met, Clay Lacy took Clark and Lyford for a ride in the Lear.

“There were about four or five other people,” Clark recalled. “We roared down the runway at Reno, took off, climbed out and did about five rolls during the climb. We turned around and flew around for about 45 minutes and landed.”

Clark says that single event probably changed his life when it came to aviation more than anything else. After school, he had returned to Seattle, and had worked a few different jobs, including helping his father out in his gas company.

“Within a year, we had a Learjet in Seattle,” he said. “We used it to fly companies back and forth across the country. My dad’s gas company in the east kind of financed the airplane.”

In 1966, Clark and Lyford founded Jet Air, which served as a Lear dealer for Canada and the Pacific Northwest.

“We’d go out and demonstrate and sell the airplane,” Clark said. “We’d land the Learjet in places where jets had never landed before. People would come out to the airplane and they’d think you were in a spaceship. It was amazing to me.”

Clark said they did that without too much success for a couple years. “We were about 20 years ahead of our time,” he said.

Clark eventually moved back to Canada to run Canadian Learjet Limited, based in Toronto. “For two or three years, we ran that,” he said. “We sold a few airplanes. But in the early part of the seventies, jets were pretty new things. At that time, there were a lot of accidents with the Learjet. It’s kind of tough to sell an airplane when one just went straight in from 41,000 feet.”

Lear Jet Industries would become Gates Learjet Corporation in 1969, following Charles Gates’ acquisition of the available 65 percent of the company in 1967. One of Clark’s employees at Jet Air had been Dick Friel. After Friel went to work for Gates Learjet as VP of marketing and sales, Clark came to work for him as sales director of the Midwest region.

“I left Canada and came down to work with Dick in Chicago,” Clark said. “We were there for a couple of years. But it was still very tough times selling jets in the early seventies.”

Then, said Clark, he left the aviation business for a couple years. He returned to Seattle, where he worked in the mortgage business and did other things. But aviation was still “his love,” so he went to work for James Raisbeck and Kim Frinell at the Raisbeck Group. The company modified Sabreliners and the Learjet Model 24 and 25. Frinell recalls Clark coming to work for them as a salesman in the late seventies.

The two had met in the mid 1960s, through sail boat racing and bunked together in the Transpacific Yacht Race (Transpac) in 1973.

Frinell, who served as vice president of operations for the Raisbeck Group, said Clark is “arguably the best salesman” he’s ever met, and tells a story to demonstrate that.

“Rockwell International decided not to accept 26 shipsets of hardware we had built,” Frinell recalled. “They were about 180,000 dollars a piece. We were going broke, and we had about eight or nine airplanes in our hangar in a variety of pieces. At that time, these machines were about four to four and a half million dollar airplanes, belonging to the likes of United Technologies, Proctor & Gamble, General Dynamics and so on.

“Joe Clark went out over the Christmas holidays to meet all of the heavies of the major companies that owned these machines to plead with them, ‘Give me money, or Raisbeck and Frinell are going to have to let go of all these people.’ At that time, we had almost 300 people working for us. Joe came back with a million dollars in his jeans. Now that’s a salesman!”

Clark worked his way up to vice president of sales, and stayed with the company for about five years, before leaving to found Horizon Airlines, a Seattle-based regional airline, with Milt Kuolt, Scott Kidwell and Bruce McCaw.

“We started working at it about 1978,” he said. “It took a couple of years to put it together. We started with three (Fokker) F27s and 35 people. When we sold the airline in 1988 to Alaska Airlines, we had 54 airplanes, 1,500 employees.”

Clark said that when they sold the airline, he had “a little bit of money,” and not a lot to do. Both came in handy for another business venture. In 1986, he had founded Avstar, Inc., through which he established a worldwide sales system to market ex-military jet training aircraft to companies and private individuals. Clark had different partners in the venture.

“I brought the first CASA jets and the first L-39s into the United States, also the first Canadair CL-41s,” he said. “I bought the Canadairs from Malaysia. We’d buy the aircraft and refurbish them and sell them. It was a pretty good business.”

He did that for about five years, and said that “chapter of his life” was full of adventure.

“I went to Chad and we flew airplanes out of Africa into France and the Czech Republic,” he said. “It was very adventurous flying these airplanes across the Sahara Desert out of Chad. They were captured ex Libyan airplanes.”

Aviation Partners, Inc.

Around that time, Clark met Dennis Washington, a Montana industrialist, and the two men became good friends. Washington, aware that Clark was an “aviation nut” who knew a lot of people in the industry, thought he was the right man to talk to when he decided he’d like to have winglets put on his Gulfstream II.

When Clark asked Washington why he wanted to put winglets on the aircraft, Washington said, “Because I want it to look like a Gulfstream III, but I think it might improve the performance, too.”

Clark admits that he didn’t really think much of the idea at that time, but that he was fascinated and decided to put together a group he thought could do the job.

“It was an aviation thing,” he said. “I got together a group of guys with whom I’d sailed; most of these sailing buddies were ex Boeing guys, like Kim Frinell and Bill Lieberman.”

Frinell, the youngest in what would be an initial group of engineers, is presently director of engineering and senior flight test engineer for API, is an FAA Designated Engineering Representative.

When Clark later contacted Frinell about Washington’s request, he discussed the possibility of a one-time supplemental type certificate.

“I called up engineering friends of mine and asked them what they thought,” he said. “At that time, that was Bill Lieberman, Peter Jennings and Larry Timmons.”

William S. Lieberman remains with Aviation Partners, Inc., today, as technical program manager. Lieberman, an FAA DER (flight test and P.E.), retired from The Boeing Company after 30 years of service, including serving as chief experimental flight test engineer responsible for the program and flight test certification for the Boeing 707, 727, 737 and 747-100 aircraft.

Frinell and Clark agreed they shouldn’t do a one-time STC, because they believed a whole company could be built “around a Gulfstream.”

“I told Joe to raise some money and we’d go and make a real analysis,” Frinell said.

Clark persuaded Washington to give them $10,000 for a feasibility study. Frinell said the next big meeting took place around his dining room table in Seattle. The group included Lieberman and a couple of new faces, Dr. Louis B. “Bernie” Gratzer and Bob Stoeklin.

The study convinced those involved that they could succeed. Although the idea initially was to take a GIII winglet and put it on a GII, that changed during the feasibility study, after Gratzer shared an idea with Clark.

Gratzer was with The Boeing Company from 1953 to 1986, serving in numerous management and project leadership positions. As chief of aerodynamics, he was responsible for the aerodynamics of all Boeing commercial airplanes. During his early career at Boeing, he contributed significantly to the design development of the KC-135, 707 and 727 airplanes.

Gratzer recalls meeting Clark when the winglet program “was just a gleam in his eye.” “The first time I met him was when we all went on a fact-finding trip to Gulfstream,” Gratzer said. “That was sort of the first step in implementing the program.”

Gratzer shared with him his idea on how to design winglets that would result in the Blended Winglet.

Gratzer recalled initially thinking that their task would be “really easy,” since Washington mainly cared about the looks, but that he soon convinced Clark that greater performance could be accomplished as well.

“I said, ‘The winglets will make the GII a much better aircraft and extend its range,'” he said. “Before we knew it, the emphasis shifted away from getting something that looks good to getting something that really works. Both worked, and did look good, and the performance was impressive.”

Gratzer, who worked in the wind tunnels for a few years at Boeing, explained to Clark that wind tunnels didn’t give accurate data on how winglets perform.

“Wind tunnels have a small Reynolds number; you have sidewall effects and compressibility and cross flow,” Clark said. “Bernie said, ‘That’s why they’ve never been shaped properly or sized properly, so I think we need to prototype it.'”

Convinced they had a winner, Clark and Washington formed Aviation Partners, Inc., in 1991, with Washington putting up most of the money for the new company.

“I put up some money,” Clark said. “We formed a 50-50 joint venture. The deal was I’d run the company and he’d be the financial partner.”

Gratzer would become the company’s senior VP of technology, and the team of engineers continued their work.

“Bernie’s contribution was that type of design,” he said. “We took it a step further and proved that it worked and patented the technology. We proved how it worked through prototyping.”

Initially, Aviation Partners, Inc. set up shop at the Flight Center, an FBO at Boeing Field.

Frinell said that their major task at that time was trying to get Original Equipment Manufacturers data from Gulfstream.

“Our trips down there failed to convince Gulfstream,” Frinell recalled. “Finally, Joe called upon Allen Paulson, CEO of Gulfstream, and he agreed, over the objections of many, but not all, at Gulfstream. The model that we created for this company was, ‘This company is not going to do anything except the fundamental design. It will do much of the analysis that needs to be done and do the flight testing and FAA certification, sales and maybe do the installations. It will leave the detail design and all the manufacturing to the expert companies that do it the best. So far, it’s been a successful model.”

Clark said they instrumented Washington’s Gulfstream II and base line flew it. “We needed a base line, because every airplane flies a little bit differently,” he explained.

The exact performance of the airplane was determined. Then, when it was time to design and fabricate the winglets, Dick Sears, Brien Wygle and Bob Lamson were some of the new faces added to the team.

Sears, who is presently chief of flight test at API and program manager on the new Hawker 800 Blended Winglet program, started out as a flight test engineer at Boeing on the B-52. His career in aviation spans 37 years, starting as a military pilot in 1945 to being a flight test department manager at Lockheed for the L-1011. Then he took on the position of lead engineering specialist and manager of product design and operational safety at the Boeing Company for the 707, 727, 737, 747 and the 757.

The oldest member of the team, Bob Lamson, just turned 90. Lamson, presently project liaison for API, is a veteran aviation consultant and former Boeing test pilot with over 30 years of experience in commercial aviation, providing technical skills in the area of aviation economics and safety. His work was valuable in providing technical assistance in the conduct of the product improvement program to obtain an STC for the GII. Lamson also provided liaison and assistance in manufacturing prototype winglets for the program.

A trip was made to Pocock Racing Shells in Everett, Wash., which would fabricate the prototype proof-of-concept winglets.

“They build their racing shells out of wood and glass,” Clark said. “We’d looked at building the winglet out of wood first, and then we decided it would be better out of glass. We built a fiberglass Blended Winglet out of fiberglass and foam. We fitted it on the airplane and we flew the same points in the sky; we got a 7.3 percent reduction in drag.”

Clark said that to determine the performance, he flew the aircraft to Palm Springs the following day.

“My partner was there with Allen Paulson,” he said. “I knew Allen from Clay Lacy and the Learjet days, because I bought my first Learjet from him. When that airplane taxied in, they were just shocked, because it looked so different. About a week later, we took it back to the Gulfstream conference and Allen announced it to everybody.”

A big hurdle they had at the time was that nobody believed them when they announced the 7.3 percent reduction.

“I remember my first meeting with Allen,” Clark said. “I told him I wanted to put winglets on a Gulfstream II and he said, ‘Joe, that’s like putting hubcaps on a Cadillac.’ I said, ‘We think we can get substantial performance increase with this new technology.’ He said, ‘If you get two to three percent, you’ll have done a great job, because that’s what my engineers tell me, and we’ve got the best.'”

Clark’s response to Paulson was that he thought they’d do substantially better.

“We were hoping for closer to 10, but we got 7.3,” he said. He said nobody thought it would work, since no one had ever done it.

“The reason they had never done it is because they hadn’t taken the time to prototype it,” he said. “They were all using the new computerized programs.”

Frinell recalled that to hire Gulfstream to do the loads analysis and to buy needed data (drawings and reports) came to a minimum of a half million dollars.

“We made a very robust winglet that we’ve had zero problems with since,” he said.

Clark believes that one of the main contributions they’ve made is prototyping new technology and then matching it with the latest computational fluid dynamics.

“We develop our own algorithms,” he said. “That’s given us the ability to do things that haven’t been done before. If we hadn’t prototyped it, we never would’ve known. If you examine most airplanes with winglets, you’ll see that winglets don’t work very well. They’re squared corners. They’re not sized properly and they’re not shaped properly, because they’re all designed in wind tunnels. That development phase was the key to our success.”

Clay Lacy was one of the first Gulfstream II owners to adopt Blended Winglet technology. In June 1995, the winglets helped Lacy and Clark set a new Gulfstream climb record and a world speed record from Los Angeles to Le Bourget, Paris, on the way to the Paris Air Show. With an elapsed time of 10 hours and 36 minutes, and an average speed of 531.8 miles per hour over the 5,638 mile great circle route, the Gulfstream IISP achieved an 83-mph gain over the previous record of 448 mph. On the return home, Lacy and Clark established a new world speed record from Moscow to Los Angeles. The following year, Lacy established seven new time-to-climb records, including a dramatic climb from sea level to 40,000 feet in just 6 minutes and 20 seconds.

“To date, we’ve converted 70 percent of the Gulfstream IIs with winglets,” Clark said. “The customers just love them. The airplanes are all owned by heads of state, wealthy private individuals or CEOs of big companies, who are wonderful people to deal with.”

Boeing enters the picture

In 1997, at the Paris Air Show, Borge Boeskov, at the time vice president of product strategy, approached Clark. Boeskov had met before with Clark, Frinell and Gratzer. Now he told him that he wanted to put winglets on the BBJ (a jet based on the fuselage of the Boeing 737), due to requests from customers that said they wanted their BBJs to look modern and sexy. Boeskov asked Clark to make them a proposal.

“He said, ‘By the way, our engineers have looked at them. We know they don’t work very well, but they look cool,'” Clark recalled. “I said, ‘Borge, we’ll make you a proposal, but if we put them on the airplane, we will get the performance, and it will be between five and seven percent, because that’s what we get.”

Boeskov, who retired as president of Boeing Business Jet in March 2002, and passed away earlier this year, explained to Clark that they had the latest wing design, which might affect performance.

“I said, ‘Well, it really doesn’t matter if they’re the latest or old wing design. We might be able to get a little more out of an old wing design, but we think we’ll get about the same,'” Clark remembered. “Borge and I made an agreement where API would spend the money to design the winglets. We would build a prototype and he would supply the airplane; if it worked like we said it would work, and we could get over the technical hurdles, they would put them on all the Boeing Business Jets.”

Clark said that when he made that agreement, not everyone thought it was a good idea.

“Everybody thought I was nuts,” he said. “In fact, my partner said to me, ‘You’re crazy. You have no chance of getting your winglets on a Boeing airplane. I said, ‘I think we do.'”

Clark said they went ahead and designed the prototypes and got them built, and then he called Boeskov and said they were ready to go. At that time, Boeskov told him he hadn’t been able to get a test aircraft.

“I had the winglets put on special stands at a hangar here in Seattle, and I told Borge I wanted to invite all the senior executives over to see them, because they looked stunning, like a work of art,” Clark recalled.

On the planned day, about 20 of Boeing’s senior executives waited in a darkened hangar until Clark walked to the center of the hangar and said, “Bring up the lights.”

“Here were these two winglets, 120 feet apart,” he said. “They all walked around them, and everybody agreed that they were beautiful.”

About a week later, Wolfgang Kurth, the CEO of German-based Hapag-Lloyd, visited Seattle. The company was buying the first 737-800.

“Borge called me and said, ‘We have to show Wolfgang the winglets,'” Clark recalled. “We took him down and showed them to him. Wolfgang said, ‘I want these on every single airplane in my fleet.’ I said, ‘We can do that, but we need to flight test and approve how they work, and we’re having trouble getting a flight test airplane.’ He said, ‘I’ll give you the flight test airplane.'”

Aviation Partners was now able to prototype the winglets. “The guys at Boeing were a little skeptical when we started,” Clark said. “In fact, they were more than skeptical. But in the end, the winglets worked exactly like we said they would.”

Clark recalls the day they did a nine-hour flight. “I was standing on the tarmac about the fourth day we had them on the airplane,” he said. “I got in the car with Jim Raisbeck and we drove across to the Boeing side, when they were coming in. Jim said, ‘Don’t be disappointed if they don’t work. I know you’ve worked hard, but Boeing has a very sophisticated wing.’ I looked at him and I said, ‘Jim, they’ll work just like I said they would.'”

As Clark watched the aircraft taxi up, the Boeing BBJ test pilot, Mike Hewitt, stuck five fingers out the window. “I knew that if that was the case, on just a cursory look, it would be fabulous,” Clark said. “We actually got a 6.7 percent drag reduction on the prototype flight.”

The result was a joint venture between Aviation Partners and The Boeing Company, formed in 1999 for applications of Blended Winglets to Boeing business and commercial jets. The company, headed by Mike Marino, will install its 500th shipset of winglets on a Continental airplane in early December.

“In the next year, we’ll save the global fleet over 50 million gallons of fuel,” Clark said. “It’s interesting; a commercial airliner flies in a month what a private jet flies in a year. They fly three, four or five thousand hours a year. Our first customers ended up being all the Germans who are technically very astute. They bought them for three reasons: they save fuel, they put less pollution in the air, and they make the airplanes quieter. That’s our biggest selling feature in Europe. The Germans were the kickoff customers for us. They really looked at our technology.”

Bruce McCaw, Joe Clark and Clay Lacy organized the Friendship Foundation. The 1988 record-breaking flight raised $530,000 for children’s charities. The flight was completed in under 37 hours. Passengers included Neil Armstrong, Bob Hoover and Moya Lear.

Clark said the acceptance of the technology came slower in the United States. “When they originally sold the BBJs, Boeing told everybody they were just for the looks anyway, and that they didn’t perform very well,” Clark recalled. “Finally, we went to Southwest and talked to them. You have to hand it to those guys; they are so thorough. They really tested our winglets, and they bought 542 shipsets from us. This year we’ll have 191 installed on them.”

Clark describes that as their “major breakthrough period.” “Now airlines all over the world have our winglets,” he said.

When interviewed in late October, Clark said they’d soon be making major announcements regarding some U.S. carriers. He was also happy to be getting kudos from Continental Airlines Chairman and CEO Gordon Bethune, through an article that appeared in “Continental’s View,” the airline’s in-flight magazine, in October 2004. In the article, Bethune calls their passengers’ attention to the fact that they’ve started equipping aircraft with the Blended Winglets.

“These winglets are about eight feet high and attach to the wingtips of the plane,” he writes. “Although they may look unusual, the winglets are helping us mitigate the extremely high cost of fuel, which is our second largest expense.”

Bethune writes that Continental, boasting one of the youngest fleets in the industry, is expecting the winglets to improve fuel efficiency by up to 5 percent.

“That may not sound like a great savings, but when you consider that we spent more than $1.2 billion in fuel last year, that small percent really adds up,” Bethune said. He also mentioned that the winglets would improve the performance of the aircraft.

“With them we are, in many cases, able to carry thousands of pounds of additional weight because of better takeoff performance,” he said.

Continental began installation of the winglets this past summer, and plans to install them on 22 Boeing 737-800 aircraft by the end of the year and on 11 757-200s in 2005. Their Orlando modification facility is handling the installation of the winglets on their 737 aircraft. Aviation Partners Boeing plans to equip Continental’s entire fleet of about 140 aircraft.

“We build 30 a month,” he says. “We’re at capacity on our Aviation Partners Boeing side.”

Reasons for success

Clark believes there are various reasons why Aviation Partners, Inc., and Aviation Partners Boeing have been successful.

“We’ve been very successful because we’ve been lucky, and well financed,” he modestly says, adding that another reason is his “great partner.”

“He leaves me alone and lets me do my thing,” he said. He laughs when he recalls that it took Washington a while to be fully convinced about their product’s full potential. “I think once we did the feasibility study, and I showed him the team, he said, ‘Those guys can probably do it.’ I don’t think Dennis believed it was as sophisticated as it was for the first five years; I think he thought it was just for the looks. A lot of people we sold to for the private airplanes bought them for the looks and were amazed at the performance.”

These days, Washington’s two sons are also on the Aviation Partners’ team.

“Kevin and Kyle now work closely with me,” Clark said. Both are board members of API and APB, and Kevin is the leader of the Hawker 800 series Blended Winglet sales team. But Clark continues to give most of the credit to his Dream Team.

“I’m blessed because I’ve had some great, great people,” Clark said. “They’re the old school engineers. The engineers today learn very specific disciplines. They’ll go out and design something and then they’ll have a meeting and say, ‘Well, that won’t fit.’ Their discipline is only in one area. The old time engineers know a little bit about load, structure, stress, aerodynamics, flutter and all the different areas, so they can look at designing something and know a little bit more about it than the new guys. We have had some very smart guys, dedicated workers. Most of my guys we started with are in their seventies.”

Not everyone in his Dream Team is an engineer. Friel, who has been with Clark in this venture for 12 years, is in charge of marketing, image and brand identity. Clark beams when he talks about Friel’s genius.

“He designs these incredible advertising programs,” he said.

Friel’s marketing tactics as VP of marketing and sales for the Learjet Company were responsible in large part for the business turnaround of the Learjet during the takeover by Gates Rubber Company. That achievement won him numerous recognitions, such as the Man of the Year award from the American Marketing Association and selection as one of the Top 10 Men in Business Aviation by Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine.

An actor who has made more than 100 commercials and acted in several movies, including “McQ,” starring John Wayne, he came back to aviation when Clark started API and needed a marketing genius. His advertising campaign for Aviation Partners Boeing has won several awards.

“We recently won best ad of the year through Air Transport World Magazine, and best ad campaign of the year,” Friel said. “That’s the second time we’ve won through them.” Although they’ve won a number of awards, Friel, the creator of such lines as “The Future is on the Wing” and “The Shape of the Future” is particularly proud of that award, since people within the industry do the judging.

“Our campaign has been recognized for its creativity and brand identity,” he said, adding that it’s quite an achievement, since they’ve been up against global companies like Goodyear, Boeing and Rolls Royce.

Besides those already mentioned, the core of his Dream Team includes Maggie Clark and Judy Galfano.

“My younger sister Maggie has been really helpful to me,” Clark says. “She’s been with me since the very beginning. She’s helped Dick Friel with the marketing and really done a superb job.”

Judy Galfano, Clark’s executive assistant, has been with him 17 years, longer than any other employee.

“She’s just the greatest,” he said. “She has a little sign on her desk that I gave her that says, ‘Would you like to talk to the man in charge or the woman who gets things done?’ She does get things done. When I introduce her as being there for 17 years, she looks at the person and says, ‘Yes, and I have every stress-related disease known to man!’ Maggie and Judy kind of typify how dedicated the people are around here. People really love what they do.” Gratzer confirms that.

“I spent my first career working for Boeing,” Gratzer said. “After that, I taught at the University of Washington in the aeronautics and astronautical department for about five years before I became associated with Joe. I’ve never looked back after that. This is an interesting place to work. I love it.”

Gratzer describes Clark as an entrepreneur par excellence who is also a very good salesman, as well as a fast learner. “This was a little bit new for Joe. I don’t believe he had been involved in this kind of technical development before. When we got to talking about winglets, he was always asking questions. Sometimes he’d ask the same question twice, but not too often,” Gratzer laughed. “He picked up on the important technical issues pretty fast.”

In describing his role in the company, Clark modestly says he’s the “catalyst” behind this technology.

“I have a great team. I carry the water buckets for the smart guys,” he says.

When pressed to ask if it was perhaps his persistence or maybe his vision that played a big part in their success, Clark finally settles on one word: passion.

“I’m very passionate about our product,” he said. “I wake up in the middle of the night thinking about things, because I really enjoy the business, and I jump out of bed in the morning. I love what we do. It’s a beautiful product. Right now, we’re kind of like the good-looking girl on the block. I don’t know how long that’s going to last, because somebody always comes up with new things, but I think that some of the new things we’re looking at in the future are going to surprise a lot of people in the industry.”

Clark says he’s also an optimist, which has helped at different times. When analyzing the issue of success, he also determines the “most successful thing” Aviation Partners has done.

“It’s probably not designing the winglets,” he said. “It’s getting them on a Boeing airplane. The wing is the Holy Grail on a Boeing airplane. I have a lot of respect for the Boeing guys, having accepted this technology and getting it more mainstream today, but it was very, very difficult.

“With most of these big companies, if a maverick little group like us comes in, the first thing that happens is the not-invented-here badge comes out. The second thing is that the engineers get a hold of it and say, ‘Now wait a minute; we can do this way better, and way cheaper.’ My question is, ‘If they can, why didn’t they do it?’

Clark is thankful to people like Paulson who gave them help early on.

“I think people wanted us to succeed,” he said. “I think one of the reasons they did is the technology was so beautiful. If you look at Bernie’s design of the winglets, they could just as easily be in the Museum of Modern Art in New York as they are on an airplane.”

Lacy, Clark’s good friend, helped in different ways.

“Clay was very skeptical at the beginning, but he’s become one of our greatest boosters,” Clark said. “He gave me a lot of advice on how to navigate through the minefields. After we put winglets on his airplane, we started setting these speed records, which gave us tremendous credibility. Then, on top of that, his fabulous photography that we’ve used to film all these airplanes from our chase planes to our original flight test airplanes has just been incredible. Every single first flight we’ve done, Clay has flown the chase on it. All the ads, all the beautiful photography and filming, that’s a big part of this, where people can actually see what you’re doing.”

Lacy is one of many people who feel Clark deserves the praise he’s received since forming Aviation Partners. “Joe Clark is an idea man,” Lacy said. “He’s always had very good ideas. When he was younger, a lot of people picked up those ideas and made them into successes. He’s finally found something he really believes in that’s big enough for him to handle.”

What’s coming up?

Clark says they’ve made so much headway that they’re prioritizing what comes next where Blended Winglets are concerned.

“On our joint venture with Boeing, we’ll be certified on the 757 in July of next year,” he said. “We’ll probably launch the 767 shortly thereafter.”

He said the 767 won’t be launched until they have customer orders.

“When we get the orders, we’ll build to that,” he said. “Between those two, there are 2,000 airplanes.” Clark said Boeing will build an estimated 3,500 next generation 737 aircraft, and out of the -700s and -800s, he estimates APB will equip 80 percent.

“Aviation Partners Boeing is always continuing to look at other airplanes,” he said. “And there are other airplanes in the private sector that API is looking at. We’re looking at a couple more business jets. The ones we like to look at are those with the longest range, because that’s the biggest bang for your buck. For example, on a Falcon, you can probably add 30 or 40 minutes range to it.”

API is also looking at a couple of military programs. “We looked at the possibility of putting winglets on the Global Hawk,” Clark said. “We figure we could give the Global Hawk another hour and a half range.”

Something coming up in Aviation Partners’ future will be more testing of the Spiroid, a close-looped winglet designed by Gratzer in the early days.

“I had some ideas about the Blended Winglet, but I also had an idea about the Spiroid, before I became associated with Aviation Partners,” Gratzer said. “I told Joe and he said, ‘I’ll make a deal with you. If you get it built, I’ll guarantee to fly it on a GII and we’ll check it out and see how good it is.’ After we did the winglet development, we went ahead and built it and prototyped the Spiroid.” Clark said they first flew the Spiroid Winglets in 1995, briefly, for 30 to 40 hours.

Although initial testing proved tremendous performance, Clark said they need more perfecting technically. “We just haven’t had the physical time to go do it,” he said. “We’ll do some more testing. I think you may see Spiroids on some of the future generation airplanes.” Gratzer said when the Spiroid was tested it was apparent that it was “an advance over the winglet.” However, the look didn’t appeal to everyone. He said that when it was on the ramp in front of the Flight Center, people would come up and look at it, all with different reactions.

Gratzer said that they’ve definitely found that trying to introduce a new idea into the aviation community is not the easiest thing to do.

“If it looks different, it raises a lot of doubt and questions in people’s minds,” he said. “The Spiroid is in that category, but people are getting used to it. The design has also evolved a little bit since the model we tested on the GII. We’ve consciously tried to make it look more futuristic, more appealing and more like it really belonged on the airplane. That makes a big difference to the aviation community as a whole. One of these days we’re going to put one on a production airplane.”

Clark says the most “fun” part of his job is the new projects.

“I’m not particularly good at the day-to-day things, but I’m great at going out and getting a new airplane and putting winglets on it,” he said. “We’re going to announce another new one in another month and a half to two months. I can’t say what it is, but it’s going to be great. People are just going to love it.”

For more information on Joe Clark and his “Way Cool Technology,” visit [http://www.aviationpartners.com/] and [http://www.aviationpartnersboeing.com/].

- Joe Clark credits many for the success of Aviation Partners, including partner Dennis Washington (left), who wanted winglets on his Gulfstream II, and Allen Paulson (center), whose first response was it’s like “putting hubcaps on a Cadillac.”

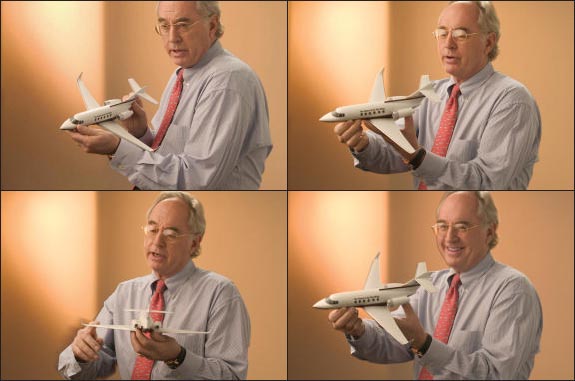

- According to Dick Friel, winglet technology is just an extension of Joe Clark’s vision “about the design, development and creation of innovative plans for planes.”

- Southwest Airlines is one of 33 major carriers in the process of upgrading to Blended Winglet Technology.