|

By Di Freeze

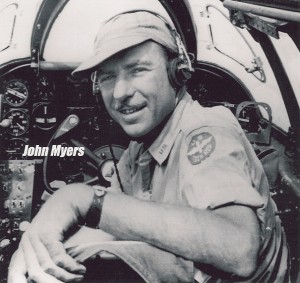

On Jan. 24, 96-year-old John W. Myers proudly walked down the red carpet at the Beverly Hilton, during the 2007 Living Legends of Aviation award ceremony. With the renowned test pilot were his longtime assistant, Janice Merriweather, and Gen. Jack Dailey, director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Later that evening, Myers was one of the many legends in attendance who were acknowledged for the roles they’ve played in aviation. A week later, the aviation industry mourned the death of Myers, who died on Jan. 31, at his home in Beverly Hills. Merriweather, who worked for him for 27 years, said he passed away peacefully in his sleep. “He will be truly missed,” she said. “He was the real deal and a fine gentleman!” During the award ceremony, Myers, Dailey and Merriweather shared a table with Barron Hilton, who introduced Myers to Airport Journals four years ago. In 2003, during a weekend at Hilton’s Flying M Ranch in northern Nevada, Myers shared his life story. At that time, Myers confirmed he’d been flying for 74 years but denied the rumor that he’d flown “every” aircraft built during World War II. “Being a top test pilot for both Lockheed and Northrop, I made it my business to fly every airplane I could,” he said. “Certainly, that wasn’t every airplane, but it was most of them.” A few decades had passed since Myers tested an aircraft, but he talked enthusiastically about his Cessna Citation II and seven-place Aerospatiale AS350 helicopter. “We were just arguing helicopters,” he said. “Mine is a hell of a lot better machine than Barron’s (MC 500-E). Mine is nice because four people can sit across the back and look out, and there’s nothing in between. It’s a great sightseeing helicopter.” Although the Citation II is a single-pilot aircraft, Myers said that when he flew it, a copilot accompanied him. “I made a vow on my 90th birthday that I would do that,” he said. “I’ve stuck by that.” |

|

Myers and Hilton might have good-naturedly argued who had the best helicopter, but Myers agreed that Hilton beat him easily when it came to the size of their ranches—both named Flying M. Hilton’s million-acre ranch, near the Sierra Nevada mountain range, includes 980,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management property.

“My ranch operation is puny compared to this,” Myers said. “It’s 18,000 acres, which is 28 square miles.”

Myers’ ranch, one of the largest cattle operations in Merced County, is in the middle of California’s San Joaquin Valley.

The logical thing to do

John Myers was working for Lockheed when Jack Northrop (right) asked if he’d be chief engineering test pilot for the Northrop Corp. Lockheed didn’t want to lose his talents and experience, so Myers ended up working for both companies throughout WWII.

John Wescott Myers was born on June 13, 1911, in Los Angeles. His passion for aviation began while he was an undergraduate at Stanford University.

“I met a guy who was going to revolutionize teaching people how to fly,” he recalled. “So, he built a little single-seater airplane.”

Myers soon began taking lessons.

“The first day, I was just to taxi it around this dirt field that was next to the stadium at Stanford,” he said. “The next day, I was supposed to take it off the ground, cut the power and land again.”

Before the first flight, Myers stayed awake the entire night, eagerly looking forward to the experience. It didn’t go quite as planned.

“I was going down this gravel runway, and I was so excited about getting enough speed to fly that I kept the tail too high,” he recalled. “I was just driving it into the ground. I hit a bump and pulled back on the stick. There were power lines in front of me. I just kept going—the logical thing to do.

“This thing had a fuel gauge that was simply a wire on a cork, and it was in front of me. When the wire got down to the bottom, I’d be out of fuel. I stayed up for about two hours learning how to fly that damn thing. I came in and landed—no problem. My fraternity brothers were all there. The fire department and an ambulance were there. I mean they were ready.”

Later, Myers bought a Viking Kitty Hawk and rebuilt it with some fraternity brothers.

“It had been in storage for a number of years; I think I paid $400 for it,” he recalled. “It took us about a year to rebuild it. I was flying from then on.”

After he had the plane flying, Myers thought it would be exciting to fly from Los Angeles to Boston, which was a five-day trip.

“I made that trip once and said I wasn’t going to do it again,” he said. “I had a friend fly my airplane back.”

Harvard Law School and O’Melveny & Myers

After graduating from Stanford in 1933, with a bachelor’s degree in political science, Myers attended Harvard Law School.

“The first day, Dean Roscoe Pound, a well-known law professor who was the head of the school, called all 800 freshmen to the auditorium and made a long and boring speech,” Myers remembered. “At the end of it, he said, ‘I want each of you to introduce yourself to the gentleman on your right and on your left. Get to know each other, because next year, only one of you will be here.’ That scared the hell out of most of these guys, but I didn’t have enough sense to be scared. It didn’t bother me at all, because I didn’t understand it. So, I played polo and did all sorts of things.”

Myers had played polo at Stanford as well. Because of the sport, he became a first lieutenant in the field artillery.

“I had to be an officer in the field artillery in order to get horses,” he explained. Later on, his participation in polo would also save his life.

Myers graduated from Harvard in 1936. He worked for a while in New York, before returning to California after his father became ill. He recalled that his father, Louis W. Myers, had earlier served as chief justice of the California Supreme Court.

John Myers test flew the P-61 Black Widow. The first squadrons of night fighters were later disassembled and sent by ship to the South Pacific. There, Myers tested them again and checked out pilots.

“He resigned at the insistence of my mother, because he was working himself to death,” Myers said.

Louis Myers then became a junior partner of Henry O’Melveny, resulting in O’Melveny & Myers.

“That’s one the great law firms in the world,” Myers said.

Myers would always be glad that his mother had persuaded him to return to California. He would eventually decide that joining O’Melveny & Myers was the luckiest thing he ever did.

“Jack O’Melveny, Henry’s son, was my boss,” he said. “He was a generation older than me. We realized that many people in the entertainment business weren’t embedded socially—they couldn’t go to country clubs and that sort of thing. We thought that practicing law in the entertainment world would be great, so we opened an office in Hollywood, in Columbia Square.”

Within a brief period, Columbia Broadcasting Systems, Paramount Pictures, Bing Crosby, Andy Devine and Edgar Bergen became clients.

“I became close to some of them, like Andy and Ed,” he said. “Ed and I were about the same age and both bachelors. We spent a lot of time together. Henry and I helped to get them recognized. After you take a guy like Bing Crosby to a country club a couple of times, and he gets to know some people, they say, ‘Hey, why isn’t this guy a member?'”

Getting close to airplanes

When the U.S. entered WWII, Myers feared he’d be called to service as a field artillery officer and have to “ride a caisson behind six or eight mules.” He decided to follow his true passion until that happened.

“I wanted to get close to my airplanes,” he said. “I left my wonderful job and took a lowly job in Lockheed’s legal department.”

Lockheed managers soon realized that Myers, with the title of junior assistant, general counsel, had talent that wasn’t being utilized.

“They discovered that I knew a hell of a lot more about airplanes and flying than most of their test pilots,” he said. “Soon, I’m asking to be excused for a day so I can ferry a Lockheed Hudson to New York or someplace.”

Then, Myers became involved in test work on the early YP-38s.

“The first eight airplanes were YPs,” he said. “That was the first time we got into what we called compressibility problems—that amounts to the speed of sound. In other words, at over 760 mph on a normal day, air compresses; below that speed, it doesn’t. That’s the so-called sonic barrier. The P-38 had two turbo-supercharged engines, so it was one of the first airplanes that could go high enough and fast enough to get into that problem. It was a real problem, because you lost control of the airplane.”

Myers’s extraordinary flying skills would eventually earn him the nickname of “Maestro.” When Jack Northrop, founder of Northrop Corp., heard about the test pilot, he sent him a message, requesting a meeting.

“I went to see Robert Gross, the chairman of Lockheed,” Myers remembered. “I didn’t think I should do that without his knowledge or permission. He said, ‘John, by all means, go see Jack. He’s a wonderful man. He probably wants to make you his chief pilot. If he does, I’m going to keep you on the Lockheed staff, because we don’t want to lose your talents and experience.'”

Myers became Northrop’s chief engineering test pilot in 1941.

“I was on the Lockheed and Northrop staff all during World War II,” he said.

The Flying Wing

A Harvard Law School graduate, John Myers went to work at his father’s firm, O’Melveny & Myers. He left the firm later to take a job in Lockheed’s legal dept., leading to test flight work on most of the aircraft built during WWII by Lockheed and Northrop.

At Northrop, where he eventually became executive vice president and director, Myers performed developmental testing on the N-1M (Northrop Model 1 Mockup) Jeep or Flying Wing. Northrop’s challenge was to come up with an aerodynamically clean design that would eliminate unnecessary drag caused by protruding engine nacelles, fuselage and vertical and horizontal tail surfaces. That desire led to the unique, boomerang-shaped aircraft.

The N-1M made its first test flight in July 1940, at Baker Dry Lake in California, with Vance Breese at the controls. When Breese left the program to test fly the North American B-25, Moye Stephens took over testing of the aircraft. Myers replaced Stephens in May 1942, and served as test pilot on the project for approximately six months.

After its initial test flight, the aircraft flew at Muroc, Rosamond Dry Lake and at Hawthorne, Calif. Poor performance plagued the aircraft, because it was overweight and underpowered. Despite these problems, Northrop convinced Gen. H. H. “Hap” Arnold that the N-1M was successful enough to serve as the forerunner of more advanced flying wing concepts. It would form the basis for Northrop’s subsequent development of the N-M9, the larger and longer-ranged XB-35, the YB-49 and most recently, the B-2.

“The B-2 is to the inch the same wingspan as the B-49, which we flew 50 years ago,” Myers said. “Jack Northrop was way ahead of his time.”

Myers said his most harrowing adventure was in the MX324 Rocket Wing, America’s first military rocket airplane. The aircraft had a wingspan of less than 30 feet and was powered by an Aerojet XCAL-200 rocket motor. The plane employed the new principles of rocket propulsion and a prone cockpit, enabling the pilot to lie flat to withstand higher accelerations and making a thinner airfoil possible.

“We didn’t have G-suits in those days,” Myers said. “Jack Northrop found out that the reason pilots blacked out was because the blood was driven down from their heads. He said the thing to do was lie down; that way a pilot can take on a lot more Gs.”

At that time, he said, they didn’t know about rockets.

“On the first flight, the idea was to leave the landing gear down on the ground,” he said. “My nose was barely above the desert, at 100 mph. I said, ‘Jack, I’ll never land this SOB again.'”

Myers also did test flights on Northrop’s XP-56 Black Bullet, an all-magnesium airplane, at Muroc Dry Lake.

“That was a tailless airplane with pusher propellers,” he said.

After WWII was over, John Myers decided not to return to his father’s firm, because he was “having too much fun with airplanes.” Instead, he took over Union Oil Company’s interest in Pacific Airmotive, the world’s biggest airplane engine support company.

Initial test flights showed the heavy nose was a persistent problem and lateral control was difficult to maintain. Before Northrop could address the aerodynamic problems, the port main-wheel tire blew out during a high-speed taxi and the aircraft somersaulted onto its back.

The Black Bullet was totally wrecked. Myers was thrown from the aircraft, but before the flight, he had strapped on his polo helmet.

“That helmet saved my life,” he said. “It always pays to play polo!”

The P-61 Black Widow and Lindbergh

When it came time to send the first squadrons of P-61 Black Widow night fighters to the South Pacific, the aircraft were disassembled and sent by ship. Myers, who had done test-flight work on the aircraft, was asked to be present when the parts arrived. Once the aircraft were reassembled, his job was to test them and check out pilots.

“That was the first airplane that was designed around radar—that is, radar that would intercept other airplanes in the air,” Myers explained. “It was very heavily armed; it had four 20-mm cannons and four 50-caliber machine guns.”

Although he was a civilian, a title seemed to be in order, because of Myers’ responsibility.

“Since I had gotten that commission when I was at Stanford, they made me a ‘simulated colonel,'” he said.

Another person in the South Pacific at that time would receive that title.

“Prior to World War II, Charles Lindbergh was outspoken in his desire to wake up our country to the fact that there was going to be a war, and that we should be arming ourselves,” Myers said. “We weren’t doing anything about it. Lindbergh was terribly concerned, but he got no cooperation from President Roosevelt. He’d been commissioned a colonel in the Air Corps after his flight, but resigned his commission in frustration and anger.”

After Pearl Harbor was bombed, Lindbergh asked for his commission back.

“Roosevelt wouldn’t do it,” Myers said. “Then, Lindbergh made a deal with United Aircraft Corporation, which was making Pratt & Whitney engines, to be a field representative for them in the Pacific area of combat. The military didn’t know what to do with him. Since he had been a colonel, they made him a simulated colonel.”

While in the South Pacific, Lindbergh began instructing pilots.

“He did a tremendous amount of good in instructing young kids how to get the best mileage out of their airplanes,” Myers explained. “He almost doubled the range of the P-38, by just telling them how to do it. It was high BMEP (break mean effective pressure), which means low rpm and high manifold pressure. Doing it that way, you could get almost twice the mileage out of airplanes like the P-38.”

At that time, Myers and Lindbergh spent quite a bit of time housed together.

“Lindbergh was an absolutely fabulous man,” he said. “He was very intelligent and loyal.”

Law or aviation

John Myers returns from a flight in Barron Hilton’s Bull Stearman, during a beautiful summer weekend in 2003. On that particular weekend, Myers arrived at the Flying M Ranch in Clay Lacy’s Lear 24.

Like other businesses, O’Melveny & Myers lost personnel during the war. When it was apparent the war was over, it was time to tally who would be coming back.

“The firm was trying to get organized, because it was starting all over again,” Myers explained. “They had a meeting; they wanted to see who was coming back and how they would fit them in. Everybody was asked what they planned to do. When they asked me, I said, ‘I’m not going back to practicing law. I’m having too much fun with airplanes.'”

Myers said that although his father must’ve been deeply disappointed, he supported his son.

Eventually, Myers would work for the Union Oil Company, which had decided to take the opportunity to help maintain and sell fuel for private airplanes and airliners.

“It had controlling interest in a company called Pacific Airmotive, which was headquartered in Burbank,” Myers said. “It had offices and facilities, including overhaul facilities, all over the U.S. and in other places in the world. At the time, it was by far the world’s biggest airplane engine support company. It looked like a hell of a good project, so Union Oil financed or backed a major stock sale of this whole thing.”

When the company was unsuccessful, Union Oil ended up owning Pacific Airmotive.

“They really didn’t want it,” Myers said. “They were kind of competing with themselves. Finally, they made a proposal to me that I just couldn’t turn down. It involved taking over Pacific Airmotive and working it up to where I could sell it. The profit was to be mine; it was a very successful operation. Several facilities helped us sell aviation fuel, spare parts and services.”

Myers became chairman and principal stockholder of Pacific Airmotive in 1954. He ran the company for more than a decade, before selling it to Purex. During that period, he had acquired the Cessna distributorship for the western U.S.—California, Arizona and Nevada.

“At one point, my partner wanted out of the Long Beach scene,” he said. “We had a lease on 45 or 50 acres, so I bought him out.”

In 1970, Myers formed Airflite, a fixed base operation at Long Beach Airport (LGB). He said deals with friends at Cessna and Northrop resulted in a sizable hangar business.

“I built a big hangar for Citation modifications and then built one for Northrop to house their corporate fleet,” he said. “I built about a dozen individual hangars before running out of steam, because I was doing it with one hand behind my back. My real business was law and ranching.”

It was then that he read that Toyota was interested in general aviation.

“I borrowed a friend’s Dun and Bradstreet and looked up Toyota,” he said. “I found they had no corporate debt and had something like $31 billion. I said to myself, ‘Skinhead, you have to know these guys.'”

In 1989, Myers became acquainted with Yukiyasu “Yuki” Togo, the president and honorary chairman of Toyota.

“I made a deal with him; Yuki took over my acreage at Long Beach,” Myers said. “We became very good friends; he took me over to Japan a couple of times. He said they’d house me in the manner to which I’d become accustomed for the rest of my life. They had no idea ol’ skinhead was going to live so damned long. But they’ve been very gracious about it. My suite is right in the middle of the airport, on the second floor, with floor-to-ceiling windows. I have about 2,800 square feet there, including my bedroom, my galley and my bar.”

Although Myers’ helicopter was most often at his ranch, he hangared his Citation at LGB.

Lucia R. Myers

Although those bachelor days shared with Bergen were fun, someone eventually stole Myers’ heart. In 1942, he married Lucia Raymond.

“I married way over my pay grade,” he smiled. “My Lucia was a Phi Beta Kappa in her junior year at Pomona. I didn’t know her then, but people said she was the most beautiful girl in school.”

Lucia R. Myers was more than a pretty face. She was the first woman to serve as a director of Pacific Lighting, the second woman to serve on the board of Bank of America and the first woman to serve as the state president of the Children’s Home Society of California. She also served as chair of the National Defense Advisory Committee on Women in Services.

“She was chair of the Marlboro School,” Myers said. “They wanted her to chair Pomona, and I begged her not to.”

The couple made their home on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills.

“I paid $48,000 for this house; that was a lot of money then!” Myers recalled. “It had a bridal path down the middle of the street. Then they decided that the path had to go; they were going to make an eight-lane highway out of it. George Murphy, an actor who later became a senator, lived across the street. I said, ‘Murph, we can’t let them do this.’ He asked, ‘What will we do?’ I said, ‘I’ll tell you what to say, but you’re the guy that has a soft violin when you talk.’ So, we went to two council meetings, and that’s why Rodeo Drive isn’t a horse path anymore.”

The Myers didn’t just put their mark on Rodeo Drive. They donated 5,000 acres of land in the Merced area to the Nature Conservancy, provided a portion of the Flying M Ranch for the development of UC Merced, and made the campus’ first $1 million contribution. Endowments were also made to Pomona College, Thacher School, St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica and the National Air and Space Museum, for which he was a board member.

John and Lucia Myers were married for 58 years, until Lucia’s death in 2000. The union produced two children, Louis W. Myers II, who died in 1993, and Lucia “Lissa” Myers Wolff.

Rescuing Bob Hoover

Throughout the years, Myers’s closest friends have been fellow aviators. Those pilots regularly get together at Hilton’s ranch, including Clay Lacy and Bob Hoover, fellow aviators from California.

Myers and Hoover had a special bond, forged in the mid-1990s, when Hoover had a legal battle on his hands. After five decades of flying, Hoover entered into a three-year-plus battle with the Federal Aviation Administration to save his medical certificate required to keep his pilot’s license. It began after he performed his usual acrobatic routine in the Shrike Commander during the 1992 Aerospace America Air Show in Oklahoma City. More than two months after the performance, two FAA inspectors filed a report stating that, based on their observations at that show, Hoover’s flying skills “had deteriorated.” They concluded that it was time for the 70-year-old to retire from air show performances.

Hoover took a battery of tests to check his mental and physical competence and the administering doctor pronounced him fit. Still, the FAA informed Hoover and his personal physician that he was unfit to fly and should surrender his medical certificate.

Hoover said the FAA took the arbitrary action without a hearing or due process and disregarded that he had flown 33 incident-free demonstrations since the investigation had begun. Pressured by Hoover’s friends and supporters, the FAA agreed to let him undergo a new, independent series of tests.

For the next 18 months, the battle would involve further physical and mental examinations and legal maneuvers by his attorney, F. Lee Bailey, and his colleague John Yodice. In 1994, Dr. Brent Hisey, a neurosurgeon, agreed to put Hoover through the most thorough exams possible. Hoover passed those tests. Hisey and his colleague, Dr. David Johnson, agreed to testify for Hoover in court, in front of Administrative Law Judge William R. Mullins.

After the hearing, the National Transportation Safety Board reversed the judge’s decision. Unsuccessful appeals followed, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Outside the U.S. was a different story. Hoover planned to start Sky Race ’94, the first pylon air race in Australia, and would perform daily at the race in a Shrike and a T-28. Before doing so, he passed Australia’s Civil Aviation Authority’s first class medical examination and a commercial pilot’s license written exam and flight check. He was given a first-class commercial airline pilot rating, which qualified him to fly anywhere in the world except the U.S.

In the spring of 1995, a friend suggested Hoover meet with Dr. Jon Jordan, the FAA federal air surgeon. Hoover agreed to additional neurological, psychological and physical tests. Jordan said he’d personally review the results and, if favorable, immediately reinstate Hoover’s medical certificate.

The report was in Hoover’s favor, but Jordan decided to have the test results reviewed by independent consultants not on the FAA payroll. Hoover received strong public support during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 1995, where thousands of posters stating “Let Bob Fly” were posted. Still, several months went by without any decision.

Gene Cernan, Barron Hilton and John Myers enjoy time together during the 2006 Living Legends of Aviation award ceremony. Hilton described Myers as a “legend of legends” and “one of the great pilots of all time.”

One evening, Hoover and Myers were guests of honor at a gala event at the Museum of Flying at Santa Monica Airport (SMO). John Travolta would be making the presentations, and David Hinson, the FAA administrator, was to give a short talk.

“They had a private reception for us,” Hoover recalled. “I had known that David was going to be there. I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, but I brought along documents I had from Great Britain and Australia.”

Hoover wasn’t sure how he would get the papers to Hinson, until Myers stepped in.

“Hoover told me, ‘I wish I could get to that guy, because I have documentation about what happened to me,'” Myers recalled. “I said, ‘Hell, Hoover, I know him very well. He used to work for my law firm. Give me the stuff.’ He gave me a fistful of papers, and I went up and grabbed the administrator. I said, ‘Hey, I have some information on Hoover.’ He said, ‘I know all about Hoover.’ I said, ‘Damn it. Promise me you’ll read this.’ He said, ‘For you, I will.'”

Hoover recalled that the event was on a Friday night.

“Hinson read the letters and Monday morning, he called and said I was back on flight status,” Hoover remembered. “The palace guard had prevented him from ever knowing the truth of the matter. Tony Broderick (the FAA’s chief of regulation and certification) had never passed along the realities of my entire case, along with Dr. Jon Jordan. For three years, Hinson never knew this case was a fraud.”

Hoover’s ordeal resulted in the 2000 passage of the “Hoover Bill” proposal from Sen. Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma. The proposal gives an FAA certificate holder the right to immediately appeal an emergency revocation to the NTSB. New final rules pertaining to the appeals of emergency revocations went into effect in June 2003.

A legend of legends

Myers’ skills as a test pilot were honored when he was inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor, in Lancaster, Calif., in 2001. Hilton acknowledged that those skills, and Myers’ passion for aviation, made him a “legend of legends.”

“He was one of the great pilots of all time,” Hilton said. “He was truly a pioneer and inspired many test pilots who looked up to him as their idol.”