By Deb Smith

L to R: Former Women Airforce Service Pilots Lorraine Zillner Rodgers and Elaine D. Harmon salute during the playing of Taps at an Arlington National Cemetery ceremony honoring women service members.

It was the summer of 1941. Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House for a third term, a new car cost $850, you could pick up a loaf of bread for under a dime, and the Dow Jones industrial average had just hit a whopping 121.

But while 1941 should have been a happy time for most Americans, many were growing increasingly concerned with what was going on in Europe. By then, both France and Poland had fallen to German control, Britain was still under siege—and Japan had sworn allegiance to the Axis powers.

On April 6, 1941, Adolph Hitler’s forces, in alliance with Hungary and Bulgaria, overran Yugoslavia and Greece as a means of strategically positioning themselves for a future invasion of the Soviet Union. In the months that followed, it would become painfully apparent America would have to make a decision regarding its neutral position on the matter.

With the menacing cloud of yet another world war looming on the horizon, the U.S. Army Air Corps now acknowledged it had a problem. As troop strength began to build overseas, the number of qualified pilots, both military and civilian, began to dwindle. However, Gen. Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold, commanding general of the Army Air Forces, was convinced there had to be a viable solution somewhere.

The shortage was indeed a crisis in the truest sense. If the United States were to enter the war, virtually every able-bodied male pilot would be needed for overseas duty, leaving a large chunk of the Army’s domestic flying program literally grounded.

Then, famed aviatrix Jacqueline Cochran (who eventually went on to become the first woman to break the sound barrier in 1953) suggested to Arnold that the Army pull the name of every woman listed in the files of the Civil Aeronautic Administration (the forerunner of today’s Federal Aviation Administration). With a solid pool of potential candidates, Cochran would recruit them to fly the Army’s domestic mission for the duration of the war.

At the same time, accomplished pilot Nancy Harkness Love presented a similar idea. She proposed hiring female pilots who held a commercial pilots license to fly military aircraft at home, thus freeing more men for combat missions. Arnold was opposed to both ideas, believing that women were “too high strung” to fly, but with heavy losses in North Africa, he knew he needed to render a solution quickly.

On Aug. 5, 1943, after much consternation, Arnold finally gave in and agreed to the “experiment.” Both Cochran’s and Love’s proposals were implemented and eventually merged to form the Women Airforce Service Pilots program, headed by Cochran.

About the same time Arnold conceded women might be the answer to the Army’s problem, brown-haired, blue-eyed Lorraine Zillner went to work for Douglas in the personnel department. A recent graduate of the University of Illinois, Zillner enjoyed the buzz of her new Park Ridge, Ill. office and the excitement of getting to meet and interview potential new employees. But what she enjoyed even more was gazing across the manufacturing floor at a never-ending sea of Douglas C-54 Skymasters.

“Oh, it was wonderful,” recalled Zillner. “Every time I had lunch or break or anything, I’d go out to the assembly line and look at those great big four-engine planes; I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing.”

However, on one particular occasion, Zillner got to do more than just look.

“One day I’m standing there looking at the production line, dreaming as usual,” she said. “This man walks up to me and says, ‘I see you out here almost every day looking at the planes. Do you fly?'”

Zillner hung her head and admitted that she didn’t.

“But I want to sooooooo bad,” she cried.

“Well, you’re in luck today, lady,” said the mysterious man. “You’re in luck because I’m the test pilot around here. Wanna go up?”

Zillner couldn’t believe her ears. She gleefully accepted the man’s offer.

“Those four big engines,” said Zillner. “It was a dream come true.”

Although this was Zillner’s first plane ride, it most certainly wouldn’t be her last.

“That cinched it,” she said. “After that, I took my paycheck and every Saturday, I went out to the local airport and took flying lessons in a little Piper Cub.”

Although she never really considered flying as a career choice while attending college, she admits to having a fascination with planes that she traces back to her childhood in Park Ridge.

“I’d be out in the backyard planting flowers and weeding,” she said. “I’d always see the planes from Chicago Municipal Airport fly over, and I’d always wonder where they were going and how that big thing could stay up in the air so long.”

Zillner would go on to nurture her girlish curiosity with books on Amelia Earhart, the famed aviator of the time.

Meeting Jacqueline Cochran

As World War II came into full swing, and America eventually became involved, Zillner said Americans began to pull together to support the effort.

“In those days, everybody was very, very patriotic,” explained Zillner. “Everybody was doing what he or she could.”

Zillner was looking to do something, too. So when the Chicago Tribune announced that Jackie Cochran would be interviewing women with pilot licenses for a new experimental training program, 22-year old Zillner knew this would be her chance.

“Oh my gosh! I called immediately,” chuckled Zillner. “I went straight down there and met her in person. She was a very dissenting type of woman; she would just sit there and look at you and fire questions. You could never quite tell what she was thinking.”

She recalled Cochran asking her if she had her license.

“No,” said a nervous Zillner.

“You don’t?” shrieked Cochran. “And you came down here to be interviewed to fly planes for the United States Army?”

“Yes,” replied Zillner.

“How could you?” screeched Cochran again, becoming even more irritated.

“Because there’s a war on, and all I want to do is fly,” explained Zillner.

“So, do you even have a logbook?” snapped Cochran.

Zillner drew a breath and slowly reached for her logbook. Reluctantly, she placed it on the table in front of Cochran.

At a minimum, potential WASP student pilots had to be 21 through 25 years of age, have a high school diploma, hold a commercial pilot’s license, and have no less than 200 hours of logged flight time. In addition, they had to be American citizens and have cross-country flying experience. As the pool of available women pilots drained, the Army dropped the 200 flying hour requirement to 100 hours. By the time Zillner applied, the minimum had again dropped.

“I only had eight, in a Piper Cub,” giggled Zillner.

A frustrated Cochran told her she had to have 35 hours to even apply for a license.

“Yes, I know,” said Zillner. “But if you accept me, I’ll get the license. I’ll fly every day and every night if I have to; I’ll do anything if you’ll just accept me into your program.”

Cochran paused, drew a breath, and then closed Zillner’s logbook, pushing it back across the table.

“Well, thank you for bothering to come down,” she said.

After that, Zillner was convinced she had blown the interview and would never hear from Cochran again. But much to her surprise, and delight, just 14 days later, a telegram from the Department of the Army arrived asking her to report to Fort Sheridan for a full physical and mental evaluation.

“I was on cloud nine,” she said. “I wish I had the vocabulary to express what I felt that day. It was simply fabulous.”

Zillner reported to Ft. Sheridan as instructed. She sailed through the testing procedures with flying colors, but there was one test she worried about. It was the one that could keep her out of the WASP program. It was the height test.

The minimum height requirement for WASP trainees was five feet, two and one half inches.

Zillner was barely five-foot-two.

“So I streeetched,” she chuckled. “And I made it—barely.”

Once her testing was complete and reviewed by the selection committee, Zillner returned home to once again receive a telegram.

“This time, the telegram was from Gen. “Hap” Arnold himself,” she said. “It was telling me to report to Sweetwater, Texas, for training.”

It was September 1943, and the war was now raging in Europe. Zillner was finally in training to be a WASP.

You’re in the Army Now (well, sort of)

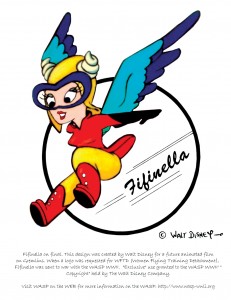

Created by Walt Disney for a feature animated film about gremlins, Fifinella became the mascot of the Women Airforce Service Pilots program. Walt Disney granted exclusive use of Fifinella by the WASP. The Walt Disney Co. holds the copyright.

Training of women pilots covered three phases—military, ground school and flying—in less than 23 weeks. This timeframe allowed for 115 hours of flying and 180 hours of ground school. As more pilots were needed and women with less flying time were accepted, the program was eventually extended to 30 weeks, with 210 hours of flying time and 393 hours of ground school.

Living conditions for the WASP trainees at Avenger Field were set up much like those of aviation cadets. They lived in military style barracks, wore military style uniforms, and ate in military mess halls.

Zillner (Class 44-W-2) summed it up as a delightful combination of “blood, sweat and tears.with plenty of blowing sand.”

“But it was exciting because everything was so new,” she said. “We would have a half a day of ground school, and then half a day of flying. In ground school we studied meteorology, maps, radios—all the different radios and their operation—Morse code, physics and recognition of planes. We took apart and put together aircraft engines, and learned how to chart on a map the different course. Oh, there was just something going on all the time. Then at the end of each segment, we were tested.”

When the trainees weren’t in ground school, they were in the air. The intense curriculum required the WASP trainees fly for a half a day, every day, and complete a rugged series of programs that included primary flight instruction, basic instrument flying, night flying, advanced flying, and even some twin engine flying.

‘We had PT-19s,” recalled Zillner. “Some of the girls had Stearmans. We also had the Fairchild, a low–wing monoplane. Now that was a honey of a plane.”

Zillner said the WASP program also included training in the BT-13 and AT-6, and some had the Cessna UC-78B, fondly referred to as the “Bamboo Bomber.”

“I think we called it that because it was pretty much made out of bamboo and canvas,” she chuckled. “Oh it was awful (to fly).”

According to Zillner, Avenger Field had character.

“It was a whole series of one-story buildings that were used as barracks,” she said. “There would be two rooms with a bathroom in the middle. There were six girls to a room. We each had a cot and a locker. We were told specifically how many clothes we could bring, and what type of clothes (including one dress) and what kind of shoes.”

Each trainee could have only one photo, which had to be placed on the inside of the locker.

“In the bathroom, between the two rooms, we had two johns, two sinks and two showers,” recalled Zillner.

And that was for 12 busy girls.

“If you could only imagine what it was like when they woke us up at six o’clock in the morning,” said Zillner. “To have everyone showered and out and ready to march to the mess hall for breakfast at a quarter of seven. It was really something.”

Train. Fly. Train. Fly. That was Zillner’s life for nearly six months. When asked what the toughest part of it was, Zillner laughed and said, “All of it!”

“We went though the identical training program the men went through,” she pointed out. “We had the same itinerary, and the ground school, and the same flights and such. And after every part of the flight training, we were tested.”

Zillner said it seemed like every week they had another test.

“It was a strain, but it was a happy strain,” she admitted. “We all worked together and we cried together—especially when one of our bay mates would be washed out.”

But they got by, because they were a team. And at times, a very creative team—especially when it came to washing clothes.

“Down in Sweetwater, we didn’t have a laundry,” said Zillner. “So our flight suits—we called ’em our zoot suits—were what we flew in all day in the Texas heat. When you came back to your room at the end of the day, they were covered in oil, sweat, and dust. So at night, we’d stand in the shower in our clothes and put soap all over them. That’s how we washed our outfits. We only got two flight suits, so we’d take the wet one off and hang it on a hangar to dry and wear the other one the next day.”

Zillner noted that no one ever complained, probably because most were just too tired. As each segment of her training ended, she grew more and more anxious to graduate. But as one particular segment came to a close, she worried more about surviving than graduating.

“I was in a BT-13 and had just ended my testing when all of a sudden the plane flipped and went into an inverted spin,” she recalled.

With all her might, she tried to open the canopy, but it wouldn’t budge. With a small dose of prayer and one humongous push, the canopy ripped open. Zillner opened her safety belt and fell out.

“I bailed out and I counted—one, two, TEN! And then pulled the rip cord,” said Zillner.

Other pilots saw Zillner’s plane go down and radioed the base, but oddly enough, no one saw a parachute. They assumed she was still in the plane. Zillner hit the brown Texas soil with a thud.

“When I finally opened my eyes, all I could see was blue sky and a cornfield,” she recalled. “All I could think was, ‘Where am I?'”

As she lay there, collecting her thoughts, she heard the rhythmic sound of approaching hooves. Two ranch hands on horseback had seen her hit and raced to see if they could be of assistance. Miles from Avenger Field, Zillner’s only hope for rescue at the time lay in the calloused and well worn hands of these two men.

“They climbed off and one cowboy sat me up and helped me remove my helmet,” she said. “When it finally came off, my hair fell out on my shoulders.”

“Oh my gosh,” gasped the cowboy. “It’s a little girl! It’s a little girl!”

Still dazed, Zillner looked around, and saw her badly damaged aircraft.

“Oh, it was a mess,” she said. “I started to cry because I realized I had totally destroyed an Army airplane. I just knew I’d never be able to fly and I’d be sent home.”

“Please don’t cry,” said the cowboy.

“But I kept crying,” she said. “And finally this one cowboy went and picked a great big bouquet of wildflowers and handed them to me.”

“Please, don’t cry, little girl,” he said.

Zillner was taken to the hospital to treat her injuries. Along with the obligatory cuts and scrapes, the pint-sized pilot had injured her leg when she hit the rudder on her way out of the plane.

“I just knew it was over for me,” she said. “And then one day after I’d been released from the hospital, I was called back to the flight line. I though this was it.”

Zillner climbed into the crew truck and was deposited back at the end of the flight line. As her instructor approached, she motioned her to take the next plane. Shocked, she asked why she was being allowed to fly again.

“I had just destroyed a government airplane; this wasn’t normal procedure,” she said.

An investigation had shown that Zillner’s plane had gone down due to a “suspicious cut in the rudder cable.”

“No one had any idea how it got there or why it happened,” she said. “No one ever said a word.”

Graduation day

February 1944 finally came and the little brown-haired girl from Park Ridge was ready to graduate.

“It was just a fabulous day because Gen. Arnold and Jackie Cochran were both there in person,” said Zillner. “Gen. Arnold arrived in his big plane from Washington, D.C. with all of his aides. It was so exciting.”

General Arnold made it a habit of personally pinning the wings on each WASP graduate. As he and Cochran made their way down the lengthy line of graduates in Zillner’s class, she noticed Cochran whisper something to Arnold.

“Jackie leaned over to him and said, ‘General, you don’t have to do all that. You can just hand the girls their wings,'” recalled Zillner. “Gen. Arnold looked up at her and just grinned, ‘Yeah, I could, but I’m loving it!'”

With a shiny set of new wings attached to her chest, a diploma in her hand and a great sense of accomplishment in her heart, Zillner was now on her way to the 5th Ferrying Group, which made its home at Love Field, just outside Dallas, Texas.

Gen. H. H. “Hap” Arnold, commanding general of the Army Air Force, was reluctant to let women fly, even though the number of qualified male pilots continued to dwindle. However, after seeing what the WASP could do, he became a staunch supporter.

The unit’s primary mission was the ferrying of military planes from their respective manufacturers to domestic stations and sometimes to points of embarkation. WASPs weren’t permitted to leave the Continental United States. In addition, Love Field also had a training mission, transport service, and maintenance facilities.

“We worked seven days a week from sunrise to sunset, “said Zillner.

She said a typical mission for her was to pick up a plane on the East Coast and deliver it to California.

“Most of the time they were training planes; those aren’t very fast,” she said. “You’d fly and you’d fly and you’d fly, and you’d look down and you felt like even the cars were passing you on the highway. It would take days to get out there.”

When Zillner landed and crawled out of the plane, the maintenance crew that had come to service the aircraft would often ask her, “Where’s the pilot?” Once the paperwork was done, and Zillner was on her own, her primary mission was to find a place to sleep and clean up.

“That was something,” she said. “Because during the war, everybody was traveling. Wives were traveling with children to see their husbands out on the coast; everybody had to be going somewhere. Many a night, some of the ferrying pilots would wind up sleeping in hotel lobbies, with their parachute bags as pillows. But we didn’t mind; we were young.”

Zillner said it made for great adventure, and she enjoyed seeing the country many times over “from coast to coast and from top to bottom.” Sometimes she got to fly new planes, and sometimes she got to fly old ones.

“Sometimes we got to fly planes that were in such bad shape, we had to fly them directly to the Boneyard out in Tucson,” she said.

According to Zillner, sometimes the planes were in such bad shape, the men refused to fly them.

“So they gave them to us,” she said. “And we’d fly them out, nuts and bolts just falling off and flying everywhere. That’s what we called flying on a wing and a prayer.”

The war winds down

It was now October 1944, and the situation in Europe was changing. The 8th Air Force had launched the first American bombing raid against Berlin, the Brits had captured the mysterious Enigma coding machine and the need for women to fly airplanes was deteriorating.

General Arnold once again penned a letter, which was read at the final graduation ceremony at Sweetwater. He said:

“The WASP became part of the Air Forces because we had to explore the nation’s total manpower resources and in order to release male pilots for other duties. Their very successful record of accomplishment has proved that in any future total effort the nation can count on thousands of its young women to fly any of its aircraft. You have freed male pilots for other work, but now the war situation has changed and the time has come when your volunteered services are no longer needed. The situation is that if you continue in service, you will be replacing instead of releasing our young men. I know that the WASP wouldn’t want that.

So, I have directed that the WASP program be inactivated and all WASP be released on 20 December 1944. I want you to know that I appreciate your war service and that the AAF will miss you. I also know that you join us in being thankful that our combat losses have proved to be much lower that anticipated, even though it means inactivation of the WASPS.

I am sorry that it is impossible to send a personal letter to each of you. My sincerest thanks and Happy Landings always.”

It was over. After more than 66 million miles and 12,650 ferrying missions, not to mention countless hours of testing and towing targets and other duties, the Women Airforce Service Pilots program was over.

More than 25,000 applied, 1,830 were accepted, 1,074 graduated, and 38 gave their life in the line of duty.

“Some of the girls went into the WACs (Women’s Army Corps),” said Zillner. “But we (WASPs) weren’t allowed to fly. The military wouldn’t accept us; it was still a man’s world.”

The problem stemmed from their “experimental” status.

“When we got our wings, the Army Air Corps didn’t know where to put us and under whose jurisdiction,” explained Zillner. “So they put us under civil service. That’s why we didn’t get any benefits. We were considered volunteers, nothing more, although we went though the same military training, wore the same officer’s insignia and uniform, and were subject to the same rules and regulations.”

With the WASP program now officially disbanded, Zillner, who had flown countless hours in the T-6, PT-17 and the BT-13, returned to her home in Illinois with nothing more than a diploma and memories. There, she began work at Glenview Naval Air Station, where she met George Franklin Rodgers, a handsome six-foot three-inch naval aviator.

They married and remained together for 33 years, until he passed away shortly after retiring from serving 32 years in the Navy as a fighter pilot. She now resides in her historic home located on the original grounds of Mount Vernon (George and Martha Washington’s home) in Alexandria, Va.

“It’s very historic,” she said. “I swear I see George (Washington) himself ride by every night.”

She’s very active in telling the story of the WASP program and is the national WASP liaison in Washington D.C. In her spare time, she enjoys oil painting and says she will take a stab at just about anything.

Although she won’t readily admit it, she knows that her service in the WASP has left an indelible mark on not only the face of the United States Army, but on the military as a whole.

“What we did has carried over in the fact that there are women military pilots today,” she said. “Also because there are women airline pilots and women astronauts. We had to prove we could do the job not only for ourselves, but for every other woman that would eventually follow in our footsteps.”

Finally, in 1977, Congress granted WWII veteran’s status to former WASPs. The Air Force’s official recommendation came two years later. In 1984, the Victory Medal was awarded to each WASP, and those who served for more than one year received the American Theater medal.