Star Trek icon Michael Dorn visits with Brian Terwilliger during the Living Legends of Aviation award ceremony in January 2007. Dorn keeps his Baron at Van Nuys Airport. Terwilliger directed and produced “One Six Right,” which traces the history of VNY.

By Di Freeze

Michael Dorn remembers the first toy that held special significance for him.

“I remember being in the hospital, for some reason, when I was a baby, and pushing this little helicopter along the ground,” he said. “It was kind of obnoxious for a hospital—it made sparks and lots of noise.”

Dorn, best known for his role as the Klingon, Lt. Worf, in multiple “Star Trek” shows and movies, also recalls his early fascination for various aviation-themed movies. One that stands out is “Test Pilot,” a 1938 movie starring Clark Gable.

“It wasn’t so much because it was about flying,” he said. “It was just a really cool movie.”

Born on Dec. 9, 1952, Dorn recalls several aviation movies that came out in the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s that impressed him. What he remembers most are “Flying Tigers,” “Flying Leathernecks” and “Jet Pilot,” which were John Wayne vehicles; “Toward the Unknown,” featuring William Holden; “The Hunters,” with Robert Mitchum; and “Gathering of Eagles,” starring Rock Hudson.

By 1973, he had added “Birds of Prey,” featuring David Janssen as a traffic helicopter cop, to his list of favorites. It would be 1986, however, before Dorn saw the film that made the biggest impact on him.

“I can watch ‘Top Gun’ over and over,” he said.

On the Road to Worf

Born in Luling, Texas, Michael Dorn grew up in Pasadena, Calif. Aviation wasn’t his only interest.

“I was always involved with music,” he said. “I played piano, and then I played flute for a lot of years. I played bass guitar in a rock and roll band in high school and for two years in college.”

While studying radio and television production at Pasadena City College in 1971, Dorn faced the draft. Hoping his military service would involve aviation, he visited with representatives from the various service branches.

“All my deferments had run out,” he said. “But I wanted to go. I thought, ‘Hey, it’s an experiment.'”

Dorn recalled the disappointment of finding out he wasn’t going to be getting close to military aircraft.

“The war was winding down, and they were letting go anybody with any type of physical defect,” he said. “A bunch of us from college got our notices. We were all sitting down there in our underwear, with our paper, getting ready to go. This guy came in, looked at my chart, saw my doctor’s note, and said, ‘Astigmatism.’ I replied, ‘It was a childhood injury.’ He said, ‘Oh, well. You’re out of here.’ You had to have perfect 20/20 vision.”

In 1973, he moved to San Francisco for three years, before returning to Southern California, where he supplemented his income by playing in bands.

Dorn said getting into acting was fortuitous.

“I was working at this department store in Pasadena,” he recalled. “I had a good friend whose dad was assistant director on the ‘Mary Tyler Moore’ show. He said, ‘Michael, you have to get in this business.’ I said, ‘Well, I studied to be a director, and that’s what I want to do.’ He said, ‘Come and work on our show; you can see if you like it.'”

Dorn began doing production assistant work.

“Then they put me in the background of the show for its last two years,” he recalled. “They kept pushing me to get in front of the camera. One of the actors recommended me to his commercial agent. I had another friend who was working on a show called ‘W.E.B.,’ which was a takeoff of the movie ‘Network.’ I got a small part on there, and an agent saw me.”

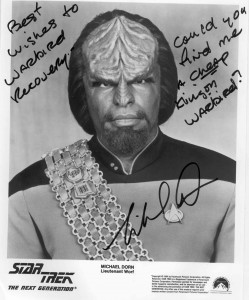

Michael Dorn, who previously owned a CASA jet, T-33 Shooting Star and F-86 Sabre, is now looking for an F-8 Crusader. He autographed this Lt. Worf picture for Gordon Page at Warbird Recovery, asking for help finding a “cheap Klingon warbird.”

Until then, Dorn’s biggest role had been as Apollo Creed’s bodyguard in “Rocky” (1976). Shortly after that, he landed the part of Officer Jebediah Turner in the NBC series “CHiPs.” He appeared in 27 episodes between 1979 and 1982. A variety of commercials came next, as well as appearances on primetime series, including “Knots Landing” and “Falcon Crest.”

“It was a little slow for a while,” he said. “In the meantime, I went back to acting school and kind of kept myself busy.”

Dorn said he learned much from his time on “CHiPs.”

“It gave me a chance to work, which is all-important,” he said. “It also gave me a chance to see how someone can be smart about the business—you save your money for the downtime. I was able to do that, and it gave me freedom to pursue what I wanted.”

What Dorn didn’t want to pursue was more roles portraying “nice guys.” That desire led him to go after a role within the science fiction genre. “Star Trek: The Next Generation” was a leap into time, taking a new crew and a new starship Enterprise into the 24th century to seek life on distant planets. For his audition for the part of Lt. Worf, a Klingon orphan raised by a Starfleet Federation corpsman, Dorn imagined how he would act if he were truly a Klingon warrior.

“You always go into an audition with a lot of people—all your friends, everybody you know,” he said. “I was in the room with a bunch of guys, but I went into another room so I could just be alone and ‘be’ this character. When I walked in for my audition, I was very surly and short, and then I said, ‘Thank you very much’ and left. That’s how it started.”

Dorn’s Worf would become a fixture on “Star Trek,” allowing him to appear in 175 episodes of “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” between 1987 and 1994, and in 102 episodes of “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine,” between 1993 and 1999. He appeared on the big screen in “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country” (1991), “Star Trek: Generations” (1994), “Star Trek: First Contact” (1996), “Star Trek: Insurrection” (1998) and “Star Trek: Nemesis” (2002). As Worf, Dorn appeared onscreen in more “Star Trek” episodes and movies as the same character than anyone else.

Dorn, who continues to appear regularly at “Star Trek” conventions, also lent his voice for several “Star Trek” related video games, as well as other video games. Since he first appeared as Worf, Dorn has appeared in a variety of TV shows as well as movies, including, most recently, “The Santa Clause 3: The Escape Clause” (2006), “Fallen Angels” (2006), “Night Skies” (2007) and “The Deep Below” (2007). He served as associate producer for “The Deep Below” and directed three episodes of “Deep Space Nine.”

He’s lent his voice for several animated projects, including “Dinosaurs,” “Animaniacs,” “Gargoyles,” “I Am Weasel,” “Superman,” “Spider-Man,” “Kim Possible” and “Danny Phantom,” and was the voice of Centurion Robot in the TV series “Duck Dodgers” (2003-2005).

What if I’m terrible?

Michael Dorn acquired his F-86 Sabre from the South African Air Force. He had it for about four years and flew it across the country a few times before selling it in 1998.

As his “Star Trek” character spread his wings, entering the Star Fleet Academy, becoming an officer on the Enterprise and eventually reaching full commander rank, Dorn was venturing into unknown territory as well.

His love for aviation had continued, taking him to air shows and leading him to collect years’ worth of Air Classics Magazines. In 1988, Greg Benson, a friend who worked on the show with him, made a suggestion.

“He flew, so we were always talking about flying,” Dorn recalled. “He said, ‘Michael, you love it so much; you have to go get your license.’ I was reticent, because I thought, ‘What if I stink at it, after all these years? What if I get there and I’m terrible?’ He said, ‘Well, you won’t know unless you try it.'”

The suggestion coincided with a writers’ strike.

“I’d been on the show for a year, and then we were off for five months,” he said. “I’d saved some money, so I went out to Gunnell Aviation at Santa Monica Airport and got my license.”

Dorn, who trained in a Cessna 172, recalls marveling at his instructor’s ability.

“He was flying and talking on the radio and doing all this stuff,” he remembered. “I’m thinking, ‘I can’t do all that!’ I didn’t know what the guy was saying on the radio; they were just going back and forth. Then, you get to a plateau, where all of a sudden, something snaps and you get it.

“I took that into all of my flying since then. You go from a single to a twin, and suddenly, there are twice as many dials and things. You’re thinking, ‘How am I going to look at all these things?’ You get to a certain point, once again, where you just realize, ‘Now I get it.’ It happens with all airplanes.”

Dorn recalls knowing that his solo was coming and being nervous about it.

“You pull over to the side and he gets out, and he says, ‘OK, take it around,'” Dorn said. “I got to the end of the runway and was getting ready to take off, and I thought to myself, ‘OK, Mister Big Talk, you wanted to learn how to fly. Let’s see what you can do.’ So I took off. I was nervous the whole time until I came around and landed. After that first landing, it was just like one of those things where you say, ‘OK, I can do this.’ I just kept going around and around. In fact, they had to tell me to stop.”

Shortly after that, Dorn purchased an Aerospatiale-Socata Trinidad TB-20.

“It has retractable gear, so I went from a 172 to a ‘complex’ airplane,” he said. “After that, I progressed rather quickly.”

From the Trinidad, Dorn upgraded to a Cessna 310 and then to a Cessna 340. An encounter with the Blue Angels forever changed the way he looked at flying.

“The Blue Angels had contacted Woody Harrelson from ‘Cheers’ to go down and do one of their media flights, and he bailed at the last minute,” he said. “Somebody told them I flew, and they called me.”

Dorn flew to El Centro, Calif., in his 340. His ride with the Blue Angels was magnificent, but the knowledge he gained was even better.

“Flying with them ruined me,” he said. “It was over, because I love jets. Then I realized that someone could own an ex-military jet. That started me down a different road.”

The first military jet Dorn bought was a CASA jet.

“It was a tiny, twin-engine jet, but it got me acclimated to jet operations—how jets work and the speed and thinking way ahead,” he said. “With the 340, you start coming down 15 or 20 miles away. With the jet, you have to be thinking 30 and 40 miles out, ‘OK, I’ve got to start coming down.'”

With his knowledge about military aircraft, Dorn decided he wanted to go through the jet process Air Force cadets had undergone.

“In the old days, they went from T-28s to T-33s, and then on into F-86s or something else,” he said. “I wanted to have that experience. All my instructors were ex-Air Force, and that’s what they flew on.”

Dorn moved up to a T-33 Shooting Star.

“It was a good experience, because the T-33 is built like a tank,” he said. “You can bounce it off the runway, and make hard landings. It’s also an old airplane, so the response on the jet engine is very slow. You come in for a landing, and if you’re slow and have to give it full power to go around, it’s going to take probably five or six seconds. That’s time you don’t want to waste. That gave me a real sense of what these old jets were about.”

Dorn had his T-33 for three years. He also tried his hand at a Mitsubishi MU-2, before acquiring an F-86 Sabre.

“It was a dream to fly,” he said. “You really have to work at screwing up.”

Dorn laughs and says his jets were fairly benign, and that the most “excitement he’s had” was with a nose-gear problem with a twin-engine Cessna.

“I had to land on the nose,” he said.

As he did with his past aircraft, Dorn based his F-86 at Van Nuys Airport and flew it across the country a few times in the four years he had it, before selling it in 1998 and acquiring a North American Sabreliner.

“I thought I was done with military flying,” he said. “It’s kind of complicated, and you have to email the FAA to tell them where you’re going to go. It’s a little bit of a hassle, just because of the nature of the beast. I just wanted to be able to jump into my airplane and fly.”

As it turned out, the Sabreliner didn’t make that happen.

“It was a bad choice, because with those corporate jets, you need a copilot,” he said. “Then, you’re at the mercy of your copilots.”

Dorn said the Sabreliner was “a fantastic plane,” but didn’t offer much excitement.

“I was bored out of my skull,” he said. “You take off, and you have your arms crossed for two hours.”

He also said that it’s cheaper to fly a military jet than a corporate jet.

“The corporate jets are current, flying airplanes,” he said. “A screw, even though it’s just a metal screw, is 10 times the price of a regular screw. With military jets, it’s so different. I remember we found two engines in Florida for the F-86. My mechanic went out there, and he was drooling over them, they were in such good shape. They were $25,000 for both of them. A Sabreliner engine is upwards of $300,000. We found brake parts—this guy had enough brake parts for several sets of brakes for us, which we got for $200, because they were just sitting in his garage.”

Dorn eventually sold the Sabreliner and again began searching for a military jet. As time went on, and he didn’t find exactly what he was searching for, he opted to keep “his head in the air” by acquiring a Beech Baron E55 prop from a friend. The plane, however, isn’t satisfying his need for speed.

“It’s a fairly slow airplane, and it doesn’t go very high,” he said. “It will basically go to 10,000 feet, but it’s a 9,000-foot airplane.”

He’s also had the chance to fly other aircraft he didn’t own. In the mid-1990s, he went up with the Thunderbirds for a flight he said was “even better” than his previous one with the Blue Angels.

“We were up in Northern California,” he explained. “We took off out of Travis and went out towards the coast. We were doing all the maneuvers and then we started flying around the San Francisco Bay at 2,500 feet. It was one of those beautiful days, and we’re in a Thunderbird jet, flying low over the Golden Gate Bridge. It was spectacular.”

Kevin LaRosa, owner of Van Nuys Airport-based Jetcopters, does film aerial coordinating and gave Dorn a chance to fly in “Ali,” released in 2002.

Michael Dorn began taking flight lessons in 1988. His first plane was an Aerospatiale-Socata Trinidad TB-20, followed by a Cessna 310 and then a Cessna 340. A flight with the Blue Angels led to his passion for flying ex-military jets.

“He called and told me they needed black pilots for a shot,” Dorn said. “They took me and Brad Lange, a captain for Delta I knew, out to LAX early in the morning. Brad was the engineer and I was the copilot. For the pilot, they hired a black actor from Nigeria that spoke French. Since Brad and I were pilots, we knew how to do this stuff. This guy had no clue; he was talking on the radio without using a microphone. They said, ‘Call the tower now.’ He says, ‘OK. Tower,’ I said, ‘You might want to use the microphone.’ He says, ‘Oh, thank you.'”

Of his 1,600 hours total time, Dorn has almost 10 hours in F-16s and eight hours in F-18s.

“I went on an aircraft carrier in the back of an F-18,” he said. “We did air operations. I think we did four traps and three cat shots. I did dogfighting in F-16s with the ‘Okies’ (465 Fighter Squadron, Tinker AFB, Okla.) and with the Fresno Air National Guard.”

He also has about six hours in the B-17 and has flown left seat in the B-1 Lancer. One airplane Dorn missed actually flying was the P-51, although he came close to flying one for “Red Tail Reborn,” the story of the Tuskegee Airmen.

“About 10 years ago, I was contacted because they were looking for pilots to fly the P-51,” he recalled. “We started to make the contacts and they were arranging for me to get training, but it fell through.”

The involvement of one of Dorn’s friends, Brad Lang, in the project, led to Dorn narrating the 2007 PBS documentary film.

Over the last few years, Dorn has considered acquiring a T-38, F-5 or F-8 Crusader. Although the T-38 is “affordable right now,” and has two engines, which he says is “always a good thing,” at the time he’s most interested in the Crusader. He’d like to “resurrect one” to participate in Heritage Flights.

There are several airplanes out there, but I’m being patient this time and trying to find the correct one,” he said.