By Larry W. Bledsoe

The Korean War is often referred to as the “forgotten war” because so little is mentioned about it in

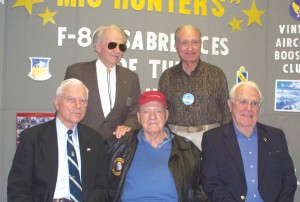

Back row: Cmdr. W. E. “Bill” Hardy, AFAA pres, & Col. Steve Pisanos, a WWII ace who was among the first to fly the P-80 Shooting Star; front row: Lt. Gen. Charles “Chick” Cleveland, Lt. Gen. Winton “Bones” Marshall & Lt. Col. Henry “Hank” Buttelmann.

history, unlike World War II or Vietnam. Yet it played a pivotal role in the history of aerial warfare. It was the first war fought jets vs. jets—a stepping stone to modern high-tech aerial warfare. Unfortunately, it was also the end of the “era of the ace”—only two aces came out of the Vietnam War and none since.

The Southern California Friends (SCF) of the America Fighter Aces Association hosted three F-86 Sabre aces of the Korean War on Sunday, March 8, 2009. According to the moderator, SCF President Dennis “Scott” Thomas, the SCF have hosted over 200 aces during these symposiums.

The first speaker was Lt. Gen. Charles “Chick” Cleveland with five MiG victories. He was with the 334th FIS, 4th FIW and was the 40th and final jet ace of the Korean War.

Cleveland said that the first mission of the U.S. Air Force is always to establish air superiority. When the North Koreans attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, all we had available were P-51s and F-82s, both recips, as well as F-80 and F-84 jets. With these aircraft, the U.S. Air Force destroyed the North Korean air force in the first three weeks of the conflict.

However, the North Koreans quickly introduced the MiG 15 into the battle, which was clearly superior to the aircraft we had in the conflict. Consequently, the Air Force focused on getting F-86 Sabrejets into Korea as quickly as possible. The MiG 15s were all based north of the Yalu River.

Cleveland was sent to Korea as an F-84 replacement pilot, but there weren’t enough Thunderjets to fly, so he and five other pilots were transferred to F-86 Sabre squadrons. He flew his first 15 to 20 missions without seeing a MiG. One night he was on his way to chow when a jeep stopped. He was asked to get in, which he did. All he could see were two “Bird” colonels sitting in front. One was Col. Bud Mahurin, 4th Fighter Group Co., and the other was Col. Harry Thyng, Wing Co.

Needless to say, he just listened to them talk. Officially they were not allowed to cross the Yalu River

Former ASAA President Lt. Gen. Winton “Bones” Marshall was the 6th jet ace of the Korean War. He had 6.5 victories, and all but two of them were MiGs.

unless in hot pursuit of an enemy aircraft. That’s when he learned that those shooting down MiGs were finding them north of the Yalu River, which changed his attitude. By the time he finished his combat tour, he was officially credited with four victories, two “probables” and four “damaged.” He was just one victory shy of becoming an ace.

Author’s note: The Yalu River runs along the border of North Korea and China. Consequently, the MiGs were based in China and were supplied by the Chinese, but supposedly were part of the North Korean air force. Just as the Taliban has a safe haven in Pakistan today, China provided a sanctuary from which the North Korean MiGs could operate. As a result, most of the aerial combat in the Korean War took place around the Yalu River.

Cleveland got his two probables north of the Yalu River. He saw one of them burning and losing altitude—a sure victory. He also saw four MiGs coming in on his tail, so he had to break off and head for home and was only able to claim it as a probable.

More than 35 years later, the Ace’s Victory Board gave him credit for that victory, but the Air Force would not. Thanks to the tireless effort of a friend, a review of Air Force and North Korean records in Washington, D.C. for Sept. 21, 1952, showed that North Korea admitted to losing two MiGs that day. One of those MiGs matched the time and location of Cleveland’s probable, and it did not match any other Air Force claims for that day. Because of this, Cleveland was officially recognized as an ace by the U.S. Air Force in 2008.

Lt. Gen. Winton “Bones” Marshall, a Silver Star recipient, was the 6th jet ace of the Korean War. He served as a flight instructor for most of WWII and then was sent to the Panama Canal Zone in February 1945. It wasn’t until the Korean War that he had the opportunity to engage in air-to-air combat. Later he served in Vietnam as vice commander of the 7th Air Force and was actively involved in Operation Linebacker. He retired from the Air Force after 32 years of service and duty in three wars.

He was sent to Korea as part of an F-84 outfit and had over 1,200 hours in the Thunderjet. Fate transferred him to Eagleston’s 4th FIG in June 1951, which flew F-86s. Marshall took over the 335th FIS when the squadron commander was sent home.

He knew from his encounters with different MiG pilots that not all of them were North Korean. He

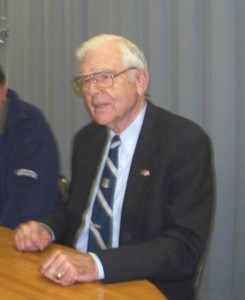

Lt. Gen. Charles “Chick” Cleveland waited 55 years before he was officially recognized as an ace by the U.S. Air Force in 2008.

reported to intelligence that the MiGs were being flown by Eastern European pilots, but they wouldn’t believe him. On his next mission, he flew close enough to the MiG to see the pilot’s red hair. Obviously he wasn’t a North Korean.

Marshall said they got word that the Russians were going to send 12 bombers to destroy an island off the coast of North Korea that was being used by the Americans as a listening post to intercept North Korean radio traffic.

The Sabres were sent to stop them. One of the bombers bailed out and one hit Marshall’s canopy, knocking it off (he lost his helmet, too). Marshall headed back to base and was preparing to land when another Sabre cut him off.

Fortunately, he had enough fuel to go around and try again. The pilot of the Sabre later told Marshall that his plane had a flame-out and he was making a dead-stick landing. Marshall got six and a half victories in Korea.

“You’re probably wondering how I could get credit for half a MiG,” he said.

Seems there was a pilot in his squadron who was scheduled to fly his last mission and hadn’t even seen a MiG. Marshall had him fly as his wingman. They found some MiGs, Marshall scoring a mortal hit on one MiG. He told his wingman to finish the MiG off, which he did. They both got credit for half a MiG.

Lt. Col. Henry “Hank” Buttelmann, a Silver Star recipient, was the 36th jet ace of the Korean War. He said all his air combat training at Nellis AFB was for air-to-ground work. So when he transferred to the 51st FIW in November 1952, he had had no air-to-air combat training.

By the end of January 1953, he only had 95 hours of “first pilot” time and flew his first combat mission in February. After several missions without seeing a MiG, he decided that he would do anything to get a MiG, which meant going north of the Yalu River. Even then he flew 50 missions before finding one.

On Buttelmann’s 50th mission, his flight encountered a bunch of MiGs and he got one but had to break off because they were low on fuel. “They reached bingo fuel,” he said, meaning they had only

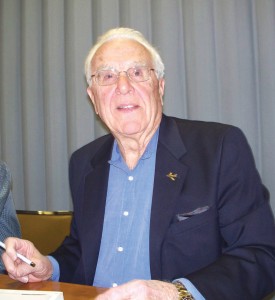

Lt. Col. Henry “Hank” Buttelmann, a Silver Star recipient with seven MiG victories, was the 36th jet ace, as well as the youngest ace of the Korean War.

enough fuel left to safely return to base with some reserve. He was down to 900 pounds, which was 300 pounds below minimum.

When they got back to their base it was cloud covered, which made it more difficult to find. They went down through the clouds and broke out at 1,000 ft. above ground level just opposite his touch-down point on the runway. So it was just a matter of turning base, then final and then land. Buttelmann said he was fortunate because they didn’t have enough fuel to go around—if they had come out of the clouds anywhere else, they probably would not have made it to the runway.

On another mission, he was down low and was hit by ground fire with a MiG on his tail. The ground fire damaged his engine, and he had to cut his power to 90 percent. But the MiG didn’t slow down and quickly passed him because it was coming in so fast. Fortunately, the MiG didn’t pursue him as he headed for home. When he got back to the Yalu River, he ran into a line of thunderstorms. He said he was lucky to make it back.

Buttelmann finally got his first victory on June 19 and was classified as an ace by the end of the month, making him the youngest ace of the Korean War. He got his 7th and last victory on July 22, 1953.

Because he would do anything to get a MiG, he had several close calls. He said he was very lucky to have survived the Korean War. Fortunately, the war ended before he finished his tour of duty and before his luck ran out.

The number of living aces is rapidly dwindling due to their ages. Like brave knights of olde, too soon we will only be able to read about them. The SCF feel especially honored and privileged to have the opportunity to meet such men as this—they are a rare breed of men indeed. We thank them for honoring us with their presence. To find out about our future SCF symposiums, visit our Web site at [http://www.Geocities.com/SCFaces@verizon.net].

Larry W. Bledsoe is an avid aviation historian and writer. He can be contacted at 909-986-1103 or at lwbcpf@aol.com or [http://www.BledsoesBooksAndArt.com].