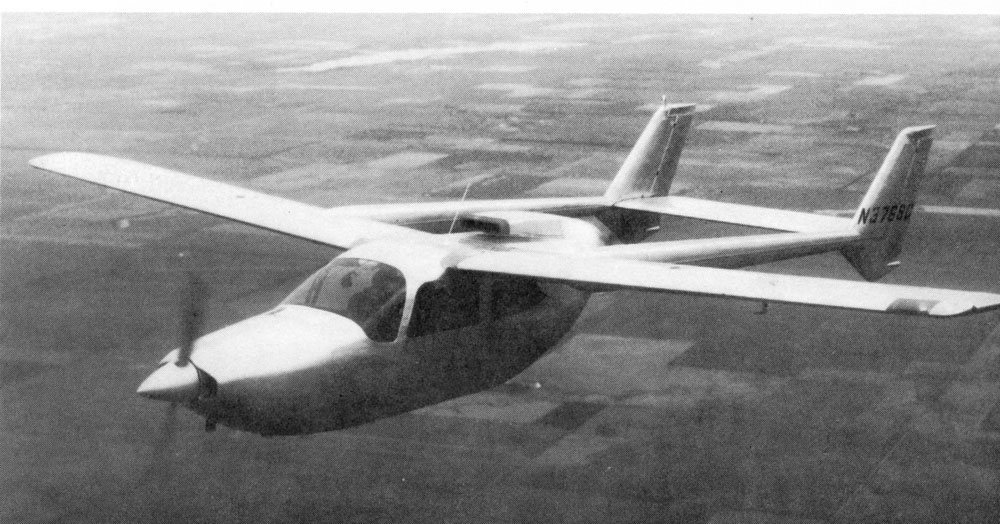

One person compared the looks of Cessna’s 1964 336 Skymaster to “Miss America posing in a swimsuit, but wearing G.I. boots.”

By Daryl Murphy

If an airplane design could evoke both unswerving devotion and total rejection, it would have to be the Cessna Skymaster. People on one side of the camp smile warmly as they describe the Skymaster as “the greatest thing since sliced bread,” while those on the other side sneer and call it an “imitation Twin.” No matter your opinion, from 1964 to 1980, more than 2,200 civil and nearly 500 military versions were delivered.

By 1959, Cessna’s sleek 310 had been on the market for four years and was successful, but its $60,000 base price put it out of the reach of many pilots who wanted multi-engine equipment. Willing to build airplanes to fit every market niche, Cessna management challenged its design group to come up with a light twin that could operate from small or rough fields and cruise at about 180 mph. Nothing economical could be adapted from the 310, so designers had to be objective in their approach. They looked at high wing, low wing, pushers, tandems and conventional twins and sketched out their ideas. In late January 1960, they got the green light for a high-wing tandem-twin concept.

Skymaster

Assigned the model number 336, the twin was to be built along the lines of the high-wing Cessna single, but with engines fore and aft, one pushing and one pulling. The unconventional fuselage would be set between twin booms that trailed off the wings and were connected to an empennage that included twin vertical stabilizers and a single horizontal stabilizer. And, although it had not been a prerequisite, the 336 could share many components and assemblies with Cessna singles.

Preliminary studies indicated the target speed could be achieved with fixed landing gear—which would keep costs down and make it appealing to lower-time step-up buyers. Continental 210 hp IO-360 engines would provide the power.

Powered by 160-hp Lycoming O-320 engines, the experimental Model 327 had a four-place cabin and cantilever laminar flow wing adapted from the 210.

It was a brilliant design, but taxing to solve the design’s unique problems. First, everyone involved had to become experts on pushers. They found that pushing an airplane through the air was a bit better than pulling it, but rear engines have inherent cooling problems because of fuselage airflow anomalies. Initially, air was gathered in forward-facing scoops (located in the trailing edge of the inboard wing) and exited aft of the engine through a complex arrangement of augmenter tubes. Flight tests showed that the exiting air really only needed a large opening in the rear of the cowl, but that created noise in the cabin, so a movable scoop was installed on top of the cowl, along with a fan located in the cowling’s rear opening.

A problem with control cables also had to be overcome. Engineers had routed empennage controls through the wing struts. It was a complicated route, filled with many pulleys working at unusual attitudes, and when flight testing began, it proved to be a high-friction operation. After seven pulleys were eliminated, the problem was solved.

Designers mounted auxiliary fuel pumps in the wing leading edges and three-quart sump tanks in the tail boom area below the wing. Large Fowler flaps, mounted outboard of the booms, were 30 percent of the wing chord and eight feet long; ailerons, five feet long, were 29 percent.

The airplane’s appearance was striking—until they installed the fixed landing gear with wheel pants. One person said it was like “seeing Miss America posing in a swimsuit, but wearing G.I. boots.”

The 336’s maiden flight was on Feb. 28, 1961. Test pilot Bill Thompson lauded its takeoff and climb performance and creature comforts, but complained about longitudinal stability and a lack of elevator power due to the high-friction controls. After some reworking, a second prototype flew in March 1962. Slightly more than a year later, the first Skymaster was delivered.

The aviation industry considered the 336 to be a landmark airplane from a safety standpoint. The loss of one engine would be barely noticeable—particularly if it was the rear engine. Torque or P-effect was cancelled, because the propellers were turning in opposite directions. And the Skymaster’s power-off, flaps-down stall speed was 52 kts (60 mph).

The 335-mph pressurized Skymaster’s average equipped price was $98,000. Only 98 were sold during its eight-year production run.

The press lauded the new airplane, but the flying public ignored it. In its first year of production, Cessna sold only 239 of the aircraft. Many pilots ridiculed the safety features, saying that they were capable of handling engine-outs in the conventional manner. In addition, the model attracted pilots with less flight time, which skewed incident and accident statistics.

The biggest problem pilots had with the plane was the ability to identify a dead rear engine. Engine controls weren’t foolproof. The pilot operating book suggested checking the gauges and then increasing the throttle to the rear engine, listening for an accompanying rise in sound.

The look of the airplane didn’t help. It certainly wasn’t as sleek as the 310—and it wasn’t even as fast as a 210. But it did have a chance. By the time the 336 hit the sales floor, Cessna had already decided to take the G.I. boots off Miss America.

Super Skymaster

The factory hadn’t done its homework and had misjudged the market. They had presumed a cadre of faithful customers would wait in line to buy the inexpensive, safe but goofy-looking fixed-gear twin that cruised at only 173 mph. In fact, it seemed the market cared only about the words “inexpensive” and “twin.”

To redesign the fixed landing gear into retractable gear, a huge number of compromises had to be made. Cessna thought it had learned that lesson in the 1950s, when it created the 210 from a 180.

Tucking and folding everything neatly into the fuselage of a Skymaster required even more complex maneuvering, and the resulting “lame duck” look of the airplane in mid-retraction or extension was to become legendary. The gear Cessna finally used put the airplane four inches closer to the ground.

The elimination of the gear drag dramatically changed the airplane’s aerodynamics. The wing angle of incidence changed 2.5 degrees, and the cowl sloped more downward. Engineers replaced the rear engine’s air scoop and eliminated the fan, the elevator had a four-inch chord increase and ventral fins were shortened six inches.

Engineers decided to add wing flaps inboard the tail boom attach, but testing showed that they had to limit travel to 25 degrees when the outboard flaps went to 40 degrees.

With a 300-pound increase in gross weight and the expectation of higher performance figures, customers pressed for five- or six-place seating. Engineers designed an exterior belly-mounted cargo pod.

The problem identifying an idle or dead rear engine was partially fixed by raising the rear engine’s idling speed 50 rpm, providing a different sound level than that of the front engine In addition, the handbook suggested that pilots lead with the rear engine throttle during taxi and takeoff.

With the new retractable gear and a few other minor changes, the former ugly duckling had become a sleek, 200-mph airplane.

The Super Skymaster flew on March 30, 1964, and 1966 model deliveries began in fall 1965. A cantilever-wing 337 was built in December 1965, but a negligible increase in performance was offset by the complex structural components and weight penalties, and the project was canceled in 1966.

When the turbo system was integrated into the 337 in 1967, the cruise speed jumped to 225 mph and the service ceiling rose to more than 30,000 feet. The pressurized Skymaster debuted with a 235-mph cruise speed. Its $76,500 base price in 1973 (average equipped: $98,000) escalated nearly $100,000 by 1980. Cessna sold only 98 during its eight-year production run.

While its nicknames included “Mixmaster,” “Push-Pull” and “Push-Me-Pull-Me,” the official moniker “Super Skymaster” was used for all 337 models from 1965 to 1971. From 1971 until production ceased in 1980, it was known simply as the “Skymaster.” Cessna built 144 military O-2As and 30 O-2Bs between 1967 and 1970, but had no turbocharged versions between 1972 and 1977.

The 327

Soon after the Super Skymaster debuted, designers conceived a lower-powered version of the 337, named the 327. Identical in form to the bigger 337, the 327 had a four-place cabin and a cantilever laminar flow wing adapted from the 210, and 160-hp Lycoming O-320s powered it.

Its top speed was projected to be 190 mph and construction techniques and structures were anticipated to be simpler. Its performance didn’t live up to expectations. Thirty-nine hours were logged on the prototype, before two 180-hp IO-360 engines were installed in May 1968. Its top speed at 3,500 pounds was 198 mph, but its performance wasn’t good enough to compete with the Piper Twin Comanche. After 44 hours of further flight testing, the program was cancelled in August 1968. The prototype was given to the NASA-Langley Research Center. Researchers there used it to test ducted propellers in full-scale wind tunnel testing.