By Terry Stephens

Ralph Bufano, retiring this month as president and CEO of The Museum of Flight in Seattle, has successfully increased the museum’s collection of aircraft by 70 percent since he took the post 14 years ago.

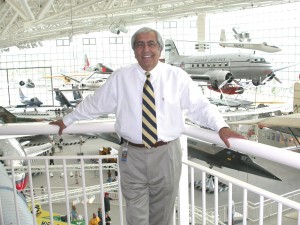

The Museum of Flight in Seattle has become the best-known private air and space museum in the world, with annual attendance closing in on a half-million visitors each year. A lot of the credit for that goes to the museum’s retiring president and CEO Ralph Bufano, an exuberant Italian with a big grin, warm, welcoming handshake and limitless vision that has set a furious pace for the museum’s development over the past 14 years.

The Museum of Flight has created one of the world’s finest aviation education programs, including its Challenger Learning Center, with an interactive mock-up of a NASA-style mission control room, and a new $1.7 million Aviation Learning Center with hands-on experiences for students in a Cirrus CR20 and flying instruction with computer software programs in aircraft simulators. For that, thank Ralph Bufano.

Globally significant historic aircraft, documents and archival treasures have been assembled at The Museum of Flight—from a replica of the Wright Flyer to World War II military aircraft, airliners of the world and space exploration displays—and more exhibits are coming. Thank Ralph Bufano.

Membership growth is setting records, and multimillion-dollar fundraising for the museum’s needs continues unabated, the envy of nonprofit air and space museums everywhere. Again, thank Ralph Bufano.

Bufano, in turn, thanks the museum’s board of trustees and its executive committee for consistently supporting him in his visionary ventures, as well as the staff of the museum, thousands of volunteers, Seattle’s aviation community and the hundreds of thousands of visitors who endorse the museum’s efforts each year by flocking to its displays and events.

While Bufano modestly credits others for creating and sustaining the museum’s sterling reputation, it’s clear that those successes would not have been achieved without Bufano’s leadership, personality and tireless efforts. Bruce McCaw, former chairman of the board of trustees until this year, expressed his thanks in the museum’s 2004 annual report, noting that Bufano’s “grand vision has guided the museum over the past 14 years.”

As Bufano leaves, the museum is at a high point in a 40-year history that began in 1965 with the formation of the Pacific Northwest Aviation Historical Foundation, created to recover and restore a 1929 Boeing 80A-1 found in a landfill in Anchorage. Today, that plane, the only one of its type in existence, is the centerpiece of the museum’s Great Gallery of historic aircraft.

Last year, the museum’s record 469,000 visitors exceeded 2003’s volume by 30 percent, admission revenue grew by 36 percent, and total operating income reached $7.6 million. That was up 12 percent over 2003, ending 2004 with $750,000 in the black, much of which will be reinvested in the museum’s exhibits and programs.

Also, net assets rose $8.2 million to $81.8 million at year’s end and gifts and pledges to the capital campaign for the J. Elroy McCaw Personal Courage Wing—the museum’s most popular new exhibit, built around the Doug Champlin collection of fighter planes—reached $48.3 million, within $5.2 million of the project’s goal.

Last year’s successes included exceeding 22,000 paid memberships for the first time, reflecting retention as well as active recruiting of thousands of new members. More than 450 paid events were hosted at the facility, and more than 1,000 volunteers devoted 77,000 hours in support of the museum. Also, a partnering relationship was created with Seattle’s new Aviation High School and the museum staff provided guidance for Snohomish County and the Boeing Co., in their development of a new $23 million Future of Flight and Boeing Tour facility, due to open this fall at Paine Field.

As 2004 closed, visitors also were enjoying an expansive new entrance to the museum, a new and larger gift store and, across the street from the museum, the museum’s new Airpark display of commercial airliners. Those included Boeing’s first 747, a 737 and 727, a Boeing VC-137—the first Air Force One—and a British Concorde SST, the only one on the West Coast.

Much of the growth, success and increased global stature of The Museum of Flight can be traced directly to Bufano, a veteran of museum and arts management with a lifelong love of aviation, a passion for his work and a vision for creatively preserving and presenting some of the world’s most historic aviation and space treasures.

Born and raised in Rochester, N.Y., the son of Italian immigrants, he learned to fly as a youth and later joined the Air Force’s aviation cadets program, following flying paths set by his grandfather and father, both military pilots.

“I was the third Ralph in the family in three generations. Two were pilots; I just thought I should be flying for the Air Force, too,” he said in a recent interview at his second-floor office in The Museum of Flight.

But that dream came to an end when the cadets program ended with the decreased demand for pilots in 1959, between wars. Bufano finished his military service in air-to-air missile installations, and then attended the University of Minnesota, ending up at the Harvard graduate school for business courses in arts administration for museum staffers.

The T.A. Wilson Great Gallery is a major attraction for more than 400,000 visitors each year, along with the new Personal Courage Wing housing the museum’s new fighter plane collection.

“Museum leadership was a small field at the time,” he said. “Most of the museum directors from around the country came there with expertise in different fields. Today, you can take undergraduate and master’s degrees in museum management, but not then.”

Those years were a turning point for Bufano, who recognized his life’s work was destined for museums. After school, and marrying his wife, Paulette, Bufano became the program director for the Corning Glass Museum in New York, and then moved on to direct a privately funded arts museum in Oshkosh, Wis., for 13 years.

During those years, he found himself part of a group working to convince the Experimental Aircraft Association to move its air museum to Oshkosh from its site at Hales Corner, near Milwaukee.

“They had a great collection but it wasn’t really a museum,” he recalled. “A couple years later they were at my door, wanting to build this museum but not having the faintest idea how to go about it.”

That’s when Bufano became the director of the EAA foundation and museum for seven years, building it, developing it and managing EAA’s annual air shows. From there he moved to Kansas City, Mo., to start the city’s new museum, but found too little funding. The same financing problems arose during a year he spent in Philadelphia, Pa., as a museum consultant and director for a struggling new Navy museum.

Afterward, he was hired to build the new $5 million, 38,000-square-foot Ward Foundation Museum in Salisbury, Md., where he spent three years developing its waterfowl collections.

“We had collections of duck decoys, that sort of thing. That wasn’t too much of a diversion from my aviation interests, though. Ducks fly, you know,” Bufano said, laughing. “It was a lot of fun building that, but my wife, who has been in museum and hospital funding and development her whole life, didn’t like the humid climate and suggested moving. I noticed in a museum publication’s jobs listing that Seattle needed a director for The Museum of Flight.”

Bufano knew the museum well. He was on the American Association of Museums’ committee that accredited the Seattle museum in 1986, so he knew the prior director and many of the board members well. One of them urged him to apply, saying the museum had 50 applicants, “…but none of them know anything about aviation.”

“I told him I might, and he said, ‘You don’t understand; we’re closing resumes tomorrow. Fax it to me.’ I did, and a couple of months later I was the new director,” Bufano recalled.

When he arrived, the museum was still $2 million in debt from completing the Great Gallery, the museum’s glass-walled “hangar” for historic planes from gliders to jets that fill the floor and hang from the ceiling. Plus, the board had committed to building a Challenger Learning Center in the gallery for interactive space age education programs for young people in a NASA-styled mockup of a mission control center, but had raised only one-third of the $750,000 needed to complete it.

“I was impressed with the board’s commitment to education,” he said. “The board backed me a hundred percent in moving ahead with that plan and the fundraising, which we got from the state, corporations and individuals. It turned out to be one of the first Challenger centers in the country.”

From there, the museum continued to add new education attractions, including an aircraft control tower exhibit overlooking Boeing Field, complete with radios broadcasting on various frequencies from FAA installations, such as Boeing Field. The support Bufano found from the Federal Aviation Administration turned out to be typical of the help Bufano found in so many projects he took on as director over those 14 years.

“We called the FAA to see if they would help us create it and they said they’d love to do it,” he said. “It was a two-year project. I told Bill Boeing Jr., a trustee of the museum, we needed probably $1.2 million to finance it. He said he could help, and then did the whole thing. It continued to go that way. The support has always been there.”

The increasing emphasis on education exhibits began with a 1993 board retreat. Bufano recalls the discussion of “what the museum should be when it grows up” and “what makes it different from any others.”

“They drew a line in the sand, deciding the museum should be the foremost educational air and space museum in the world by 2003, giving me a decade to do it,” he said.

And he did—but always with the board’s help, and often with the board’s money. That board today includes James Johnson, his successor as chairman, who is retired as CEO of Gulfstream Aerospace Corp. It also includes Bruce McCaw, John M. Fluke Jr., James Curtis, Tom O’Keefe, William Ayer, William E. Boeing Jr., Clay Lacy, Alan Mullaly, John Nordstrom, Frank Shrontz and Joseph Sutter.

“With the board’s strong support, we’ve been able to build our education department from four people then to 42 fulltime staff now,” he said. “That’s the largest education staff of any air and space museum in the world. All of that grew from that impetus from the board.”

Yet the board never lost sight of developing the museum’s air and space exhibits either, he said.

“We’ve increased our collection by 70 percent since I’ve been here, but that meant finding space for them, too,” he said. “In an art museum, you just put the paintings in a vault. But with aircraft, they’re not small; you have to plan for the space, too.”

To help set their priorities, Bufano and the board mapped out the remaining historic aircraft they wanted to get for the museum, and then went after them. Landing the Champlin fighter plane collection, then on display in Arizona, was a quantum leap forward for the museum.

“The board didn’t waver when we decided to build our fighter collection; we were very weak in that area,” he said. “When Chaplin’s collection became available, the board supported me through nearly a year of negotiations. No money was committed for it but we knew we would get it. It was a major undertaking.”

Housing the aircraft properly was part of that major undertaking, since there was no place to put any of them when the collection was first acquired. In 2002, construction began on the $54 million Personal Courage Wing of the museum, which opened in 2004 with two floors for displaying World War I and World War II fighter planes in an unusual museum presentation. Each plane is in an historic diorama setting, with reenactors talking to visitors about the plane’s wartime roles in world history.

“We decided the best way to exhibit the planes would be to tell the story of the people, not just the aircraft,” Bufano said. “That set us apart. Now, we’re working on the next step, developing the world’s finest air transportation collection for our airpark. First we found a 747, 737, 727 and the first Boeing 707 presidential jet, Air Force One. Then, when the Concordes were retired, we got the last commercially flying model, Alpha Golf. Now, we’re working on a Constellation, a nostalgic plane that is an important part of the evolution of passenger service.”

Personally, one of Bufano’s favorite acquisitions for the museum—now displayed in the Personal Courage Wing—is an original of the world’s first fighter plane, the Caproni Ca 20.

“I visited the Caproni family to discuss it,” he said. “I knew others had tried to buy it. It was hidden for 85 years in a monastery in Italy, on the second floor, to protect it from destruction during World War II. Since I speak Italian, I was able to negotiate with the family in Italian. It’s so rare that the board decided we should not even restore it—just display it as we found it, with its original fabric.”

One of Bufano’s most recent and rewarding experiences involves a London phone call from a former British Broadcasting Co. reporter who said he had heard that The Museum of Flight was the place that should have his “rare recordings.” What he had was a collection of interviews recorded during World War II with Gen. Paul Tibbets, then pilot of the “Enola Gay” on its nuclear bombing mission over Japan. But there was more; he offered 82 hours of oral history interviews with each member of the bomber crews of both the “Enola Gay” and “Box Car,” the B-29 that later bombed Nagasaki.

“The man had kept the recordings to himself all these years, but he and his wife needed the money and wanted to sell them,” Bufano said. “They had many offers, including $175,000 from the Japanese, but turned them down. I told him, ‘I don’t have $175,000,’ but he said there were a lot of people in the world, many of them history revisionists, and he didn’t want them to have the tapes; he wanted us to have them. He said he would take whatever we could offer him.”

Bufano told the board that the tapes belonged in America. The board agreed, but said those on the board had already committed to various fundraising activities. Bufano asked if he could call the trustees to see who they knew who might be interested. One by one, his calls for references generated donations instead.

“One of those who responded told me he was ready to get on a ship to Japan when that bomb dropped and he would gladly give me money for the tapes,” Bufano said. “Altogether, we not only raised the money to buy the tapes, but also to hire someone for two years to transcribe the tapes for the museum’s library. That really moved me.”

Along with the museum’s awards, Bufano has enjoyed his own personal recognition, too, such as his 2002 election as a fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society and becoming a member of the prestigious Federation Aeronautique Internationale, which presented him with the Paul Tissadier award for services to aeronautics and airsports.

Reflecting well on Bufano’s national stature, he was named in 2003 to a group of museum experts charged with assessing whether the operating standards of the U.S. Air Force Museum, the nation’s largest and oldest military aviation museum, meet today’s professional criteria for comparable museums.

Today, he’s a Museum Assessment Programs accreditation surveyor for the American Association of Museums, as well as western representative to the International Association of Transport and Communications Museums.

In retirement, he plans to continue as a museum consultant whenever opportunities arise and to spend more time with his wife, Paulette, whom he credits with contributing her own expertise to The Museum of Flight’s fundraising campaigns for many years. Their children, Michael in San Diego and Michelle in Seattle, are both married and each have two children.

Thanks in great part to the fertile mind and tireless energy of Ralph Bufano, Seattle’s nonprofit Museum of Flight is one of the world’s best managed private aviation museums, with a world-class collection of historic aircraft and artifacts professionally preserved and imaginatively displayed to inform and inspire present and future generations.

The Museum of Flight’s newest major attraction, the building partially seen in the distance to the left of the museum’s Great Galley, is the $54 million Personal Courage Wing, filled with World War I and II fighter planes.