By Di Freeze

As a youth, Murray Q. Smith found a unique way to honor his father, an insurance agent. He wrote a poem for him.

“His old horse died, and his mule went lame, and he lost his cow in a poker game,” the poem read. “A cyclone came one summer day, and blew his house and barn away, then an earthquake followed to make it good, and swallowed the ground where his house had stood. The shock was so great, that he up and died, and his widow and children wept and cried, but something was left for the kids and wife, ’cause he had insurance with Bankers Life.”

Although Smith’s poem was never published, he would one day see his name in print. In fact, it’s been constantly in print for over three and a half decades. Besides his love for writing, painting and drawing, by the time he was five, Smith had also developed an interest in flight. Through Alexandria, Va.-based Professional Pilot magazine, he would eventually “squeeze together” his love of writing and aviation, as his creation’s editor and publisher.

Smith, who was born in Chicago and grew up in Waukegan, Ill., attended Lake Forest College and later, the University of Illinois School of Journalism, where he received a BS in journalism. After graduating, he worked for the Leo Burnett Advertising Agency, where he mainly did technical writing. He worked there for about a year, before applying for the Navy. He entered the military in 1958.

At that time, he had already had his private pilot’s license for about a decade. He passed his flight physical and thought his dream of flying military aircraft was about to come true, but he was told that the Navy really needed people who could write. That opened his eyes to something he hadn’t yet realized.

“I found out that very few people can really write,” he said. “People can write long, but they can’t write short. They ramble, and they don’t understand topic sentences, or where they’re going with an article.”

Although that knowledge would come in handy years later when he would take pilots under his wing and train them to write, he was disappointed when he was told the Navy needed a technical journalist to write up antisubmarine warfare reports.

“It was a bitter disappointment,” he said. “They said, ‘Well, you’ll finish this tour and then you can go. The tour was 18 months. They sent me down to Key West, Florida, to a squadron called VX-1. It was part of the Navy’s RDT&A—Research Development Test and Evaluation. Our squadron was part of Test and Evaluation.”

Part of his job was evaluating things like autopilots, flight directors, deicing boots and weather radar. In order to write up his reports, Smith participated in antisubmarine warfare development exercises for up to six hours at a time. He realized that three groups of people would benefit from the reports—the military, which had to fly in all types of weather, airlines, and a growing group of “corporates.” He also came up with an idea for a magazine.

“While I was flying over the water inside a Navy patrol airplane, I dummied up a magazine called Corporate Pilot,” he recalled. “I came up with various sections.”

When that 18-month tour was up, Smith again thought he was on his way to Navy flight training at Pensacola, after passing the flight physical, but a commander under Admiral Nimitz invited him to join the Navy Chief of Information Office at the Pentagon. Smith told him that he really wanted to fly military aircraft.

“He says, ‘You’re going to have to pay back the school; remember that. The school is 18 months. You have to pay it back with twice the length of school; that’s 36 months. I’m offering you a chance to get 18 months in the Pentagon, and then you get out and do whatever you want. You can buy your own airplane,'” Smith recalled the commander saying. “I could get out that way with another 18-month tour, so that’s what I did.”

At CHINFO, Smith worked on Navy, Air Force and Army projects.

“I worked under Admiral Hyman Rickover (“Father of the Nuclear Navy”) on something called Special Projects,” Smith said. “I had a great time. But way down deep, I’m still sad that I didn’t take the Pensacola trip.”

But Smith did fly privately throughout his time in the Navy, and was instrumental in the setting up of a Civil Air Patrol base in Key West.

Professional Pilot

After leaving the Pentagon, Smith flew a Piper Tri-Pacer before earning enough money to buy a brand new Beech Musketeer. He recalls an important trip in 1966 made in that aircraft. On a rainy day, he arrived at Nationwide Insurance Company, where he visited with the head of the flight department, showing him his magazine dummy.

The response was that the format was great, but that the name itself, Corporate Pilot, was demeaning.

“He said, ‘When my wife and I go out to a country club or something, they ask what I do. I don’t tell them I’m a corporate pilot; they put that in a place below an airline pilot. I say I’m a professional pilot. Try that title and see if that doesn’t get you more response from the pilots,'” he recalls the flight department head saying.

After that, Smith tried an experiment.

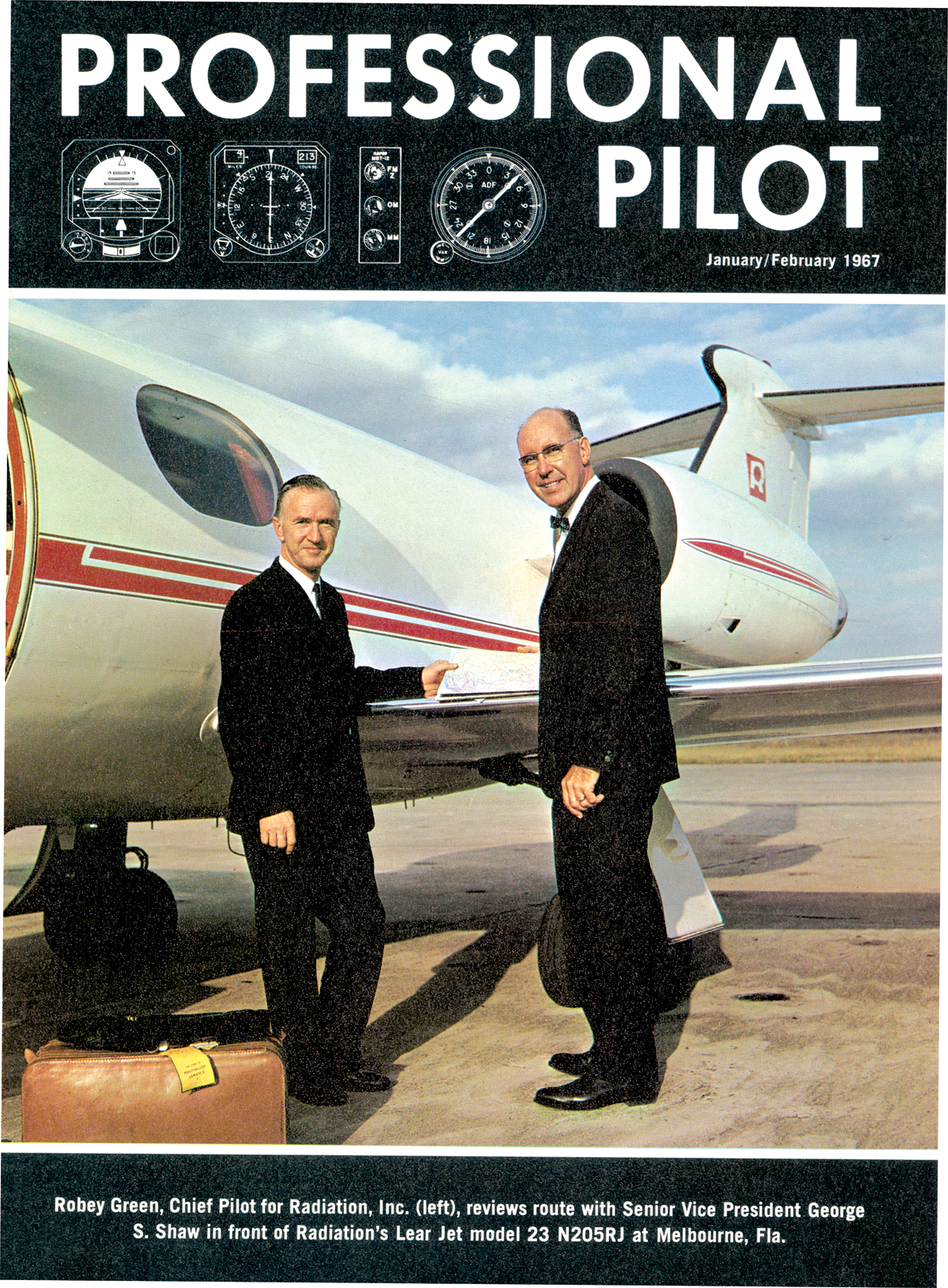

“On my little dummy, I had this little flop-over thing: Professional Pilot, Corporate Pilot, Professional Pilot, Corporate Pilot,” he recalled. “At least nine out of 10 preferred Professional Pilot. So when the first issue was published in January 1967, it was Professional Pilot. By the way, all the departments of the magazine that are there now were there then. Everything mainly stayed the same—except the name.”

Smith, who presently owns a Baron, a Saratoga and a Sundowner, is a certified flight instructor and the only publisher he knows of in this field with a valid ATP. He believes he spends more time with chief pilots and flight departments then any of his competition. That’s been true since the early days of his magazine, when he began mentioning that he was available to fly in the right seat.

Smith says his formula for Pro Pilot was unique and very simple.

“First of all, I never saw a corporate aviation magazine where they showed on the front cover why the guys had airplanes,” he said.

He refers to the front page of Pro Pilot as his “ham-it-up 4-P cover.”

“Pilot, President, Plane and Products,” he explained. “It’s unique with Pro Pilot. You’ll see that on every cover. For example, we recently featured Kohler Plumbing. We had the president sitting in the bathtub; behind him is the chief pilot, and behind him are the airplanes. When we did Purina Dog Chow, we had the dogs and the dog food; the key executives were pushing a shopping cart with the dog food and the airplanes behind them.”

When Smith called to set up an interview with Jeff Bluestein, the president of Harley-Davidson, he asked him to wear a Harley-Davidson cap and shades, and to be sitting on a Fatboy. Bluestein wholeheartedly agreed.

Smith says it’s very important for Pro Pilot to focus “more on people than it does on airplanes.”

“When I started flying, you had to let the airplane spin, and then you had to roll it out on a point,” he said. “They don’t do that anymore. When you did the spins, you had to wear a parachute. The rest of the time, you didn’t. I remember my instructor saying, ‘Murray, I know you just love these airplanes, but don’t get so attached that you ride it all the way down, ’cause this airplane’s a machine; it has no brain. It’s people that make it fly. Without the person, it doesn’t fly.'”

That’s when Smith began looking at “who” the people in the cockpit are. He said a key part of Pro Pilot is recognition.

“When these people appear on the cover, they each get a plaque,” he said. “And when they win in a survey or something, they get a very nice plaque.”

Part of that recognition is in the form of pictures.

“You’ll notice there are a lot of mug shots, a lot of people pictures,” he said. “At one time, I went to visit ‘Dunny’ Dunsworth, the chief pilot for El Paso Natural Gas in El Paso, Texas. On the wall in his flight department, he had matted—with a big mat and a fairly big frame—this little mention that he had when he got promoted to chief pilot. I said, ‘Dunny, look at what you’ve done! You’ve got this big thing for these few little lines of type.’ He says, ‘Well, it was the first and only time I was ever written up in a magazine!'”

Editorial canons

Smith has three editorial canons. The first is “Accuracy ahead of speed.”

“If a magazine is going to be late, let it be late, but make it accurate,” he said. “I’ve never been sued. I’ve never had a problem with anybody in 38 years of publishing this magazine because I check everything out. Like these front covers; Paul Richfield from BCA came and worked with us for a while. He said, ‘At BCA we wondered how you could do these covers. We tried; they turned us all down.'”

Smith responded with one of his father’s favorite sayings: “The best surprise is no surprise.”

“He says, ‘What do you mean by that?'” Smith recalled. “I said, ‘I send it all back.’ He said, ‘Oh, we wouldn’t do that—freedom of speech, freedom of journalism…’ I said, ‘If anybody’s going to write an article about me, I’d like to see it before it’s published, and I imagine that Kroehler Furniture and Kohler Plumbing and Ralston Purina and Harley-Davidson want to see it, too.'”

Smith says that many of the companies profiled for the front cover of Pro Pilot are members of the Conquistadores del Cielo, one of the world’s most exclusive clubs.

“That’s the richest of the rich, and the most successful of the successful,” he said. “If I screw up with one of them, I’ve screwed up with all of them. If they want a comma where I don’t have a comma, or want me to take out a comma where I do have a comma, I do it. Does it hurt the story? I don’t think so.”

Smith says he calls it “responsible journalism.”

“I don’t do yellow journalism; it doesn’t pay off,” he said. “My competition, AIN, is a hot news publication; they want to get stuff out and beat me to the punch. I don’t care; they can beat me to the punch. But mine will be well researched and signed off. So, my law is, ‘You don’t work for me unless you send it back.'”

Smith’s second editorial canon is “Advertising follows readership.”

“I want to get the editorial content first,” he said. “If it’s good editorial content, the advertising will follow. Editorial ahead of advertising, readership ahead of advertising. If you have the readership, you’ll get the ads.”

Smith says his most important editorial canon is “People are more important than machines.”

“People are more interesting than machines,” he said. “All the way through Professional Pilot magazine, it’s really a People magazine in aviation. There’s a lot of people stuff, a lot of people pictures, a lot of people editorials. Having people on the front cover was inherent in the earliest design. And we have the largest letter section of probably any trade magazine, or probably any magazine.”

Smith explains that the sections in Pro Pilot reflect transmissions in the aircraft.

“Our letters section is called Squawk Ident,” he said. “The lead editorial is Position and Hold. My last editorial that closes the book is Outer Marker Inbound.”

He points out that another big difference between Pro Pilot and their competitors is that pilots in the field write the editorials.

“For Position and Hold, probably a guy like Duane Futch, chief pilot of Wal-Mart,” he explains. “Outer Marker Inbound, someone like David Newell of Vanity Fair. The guys in the field write about everything—salaries, new equipment, FBO services.”

He explains how his system works.

“A lot of people who don’t know me think, ‘Oh, Murray just sits back and twiddles his thumbs, and the whole book gets written.’ I review all these articles, but I also have some very good editorial people on staff, and their main job is to cook the pie. My brother and I used to go out in the woods around Waukegan, and we’d bring back wild berries—with the stems, leaves and everything. My mother would clean it up, take off the leaves and the twigs and all that stuff, and she’d make a very civilized, nice, delicious pie. We do exactly the same thing here. We get people and we teach them to write.”

For example, Clay Lacy does flight checks for Pro Pilot.

“He writes editorials from time to time,” Smith said. “That’s real ‘horse’s mouth’ stuff.”

The December 2004 cover of Professional Pilot, featuring VF Corporation, follows Murray Smith’s “4-P” design: Pilot, President, Plane and Products.

Lacy began writing for Smith when the last person covering that area made some demands Smith wasn’t willing to meet, including twice as much money per article and the guarantee of a flight check every month.

“I said, ‘I can’t do that; there aren’t that many new airplanes,'” Smith recalled. “He says, ‘Or else I’ll go to BCA or AIN.’ That’s what they all say, because those are my two competitors.”

In the next Monday morning meeting, Smith asked who they should get to replace that writer. He heard several names, but announced that his idea was Clay Lacy. Those in the meeting asked how he would get Lacy to agree.

“They said, ‘Well, are you going to write him a letter or call him?'” Smith recalled. “I said, ‘No, the only way to sell’—which is what corporate aviation is all about—’is belly to belly, face to face.’ That’s why I have a corporate airplane—to go and say something, to give someone a slap on the back, to share a meal with them. That wink of the eye, a handshake, you don’t do that over the phone. I said, ‘I’m going to go out and see Clay Lacy.'”

Smith made the trip to Clay Lacy Aviation at Van Nuys Airport.

“Clay was very magnanimous,” he said. “I went out with my wife, and he says, ‘How would you like to see my place up near Fresno? We’ll fly up there in my Lear, and we’ll have dinner.’ So, we fly up to this place, he parks the airplane. He has this old rebuilt car there—real nice. We go to a Mexican restaurant and I say, ‘Clay, I want you to do my flight checks.’ He says, ‘I’ve never written anything in my life.’ I said, ‘Would you like to do it? You’ll get better.’ He says, ‘I’d like to do it, but how are you going to pull this off?’

“I said, ‘You’re going to have a tape recorder next to you and you’re going to dictate. I’m going to have a photographer and a writer who’s going to do a verbatim transcript. He’s going to get someone to edit it, so it doesn’t ramble, and it’s going to go back to you. You’re going to make your changes, and that’s going to be the article.’ That’s what we do to this day.”

That worked out so well that Smith uses the system with other pilots as well.

“How do you think Bill Clinton writes a book, or George Bush, or Heidi Fleiss?” he asks. “They do the same thing.”

Smith says Pro Pilot has earned the nickname “Pro Pilot University” because he’s taught so many other journalists who are now at competing magazines, such as Tom Haynes, editor of AOPA Pilot, and William Garvey, editor of Business & Commercial Aviation (BCA).

“There are scores of others,” he said.

PRASE and other surveys

Professional Pilot has conducted various surveys since the beginning.

“We do headsets, avionics, turbine engines, engine overhaul,” he said. “We do a survey on everything imaginable that touches the life of the corporate pilot—probably except his relationship with his wife. We might do that…”

He traces his interest in surveys back to his Navy background, when he did test and evaluation out in the field.

“I ask, ‘What do you think about the performance of these aircraft? What do you think about the follow-up service? How good is the product support?’ We’ve helped bring product support to the forefront. People would say, ‘Product support? What’s that?’ I’d said, ‘You might call it customer support; we call it product support.’ I’ve always done research; I’ve always asked the pilots what they think.”

The very first survey they did was regarding corporate pilot salaries, by aircraft type.

“No one else did a corporate pilot salary survey,” he said.

After that survey, he came up with one for fixed base operations, which became the Preferences Regarding Aviation Services and Equipment, or PRASE survey.

“That one started in 1974,” he said. “We did other things with the FBOs, but we evolved the FBO survey. In fact, that’s still evolving.”

The annual survey recognizes a variety of services and products, including best employee, catering, fuel brand and weather service. Each year, five new judges, who are active professional pilots with a wide range of experience using FBO services worldwide, are chosen to verify ballot authenticity and resolve any discrepancies.

“At first, we brought the ballots into the office, and the people in the office counted them,” Smith said. “Then, my competition, looking to degrade me, said, ‘Murray could cheat; he could count those ballots.’ Mike Waterman, the director of an FBO in White Plains, said, ‘You know, Murray, you ‘could’ count those ballots.’ I said, ‘Mike, next year, I’m going to make you a judge; you’re going to see the ballots.’ Then I thought about it, and I said, ‘Why only Mike Waterman? I’ll have a group of judges.’ Every year, we do now.”

In 2004, judges, various FBO managers and some pilots weren’t happy with recent changes to categories, which were made by popular vote.

“We brought in pilots to review these, and then the pilots came up with better ideas,” Smith said. “They said, ‘Signature Flight Support always wins because it has the most bases, and everybody usually votes for their home field, so they’re going to get the most votes, and that’s unfair. What you need to do, Murray, is have categories. The fairest thing, regardless of the size of the facility, is to grade them on the line service and the customer representatives and the facility and the amenities, and the value they get for what they spend.’ So, with the help of these corporate pilots and service judges, we came up with these different categories. The survey evolved to that.”

Because of the recent complaints, Smith has been working with his control group to revise the categories for the new 2005 PRASE ballot.

“I do that all the time,” he said. “I’m not a know-it-all.

He said Pro Pilot is always looking for new input.

FlightSafety International Founder Al Ueltschi poses with Murray Smith during the 2003 NBAA convention in Orlando, Fla.

“It evolves slightly because of the reader input, the reader involvement,” he said. “I don’t know of any other publication out there that has that kind of reader involvement. I’m always asking my readers what they think of articles and what they want in the book.”

As an example, Smith recalls a comment he received when they were doing a product support survey on avionics about 10 years ago. A chief pilot had written the comment in longhand on the bottom of a survey form.

“He says, ‘Why do you survey us on product support for avionics? These days, avionics are solid state; you can pour coffee and Coca Cola on the equipment and it will still work. We would like a survey on the user-friendliness of the equipment. Why don’t you do something like that?'” Smith recalled. “So, I took my big black lab, ‘Peter,’ for a walk, and I thought about that. I came up with OPTICS: Operation, Presentation, Technical Advancement, Information, Construction, Satisfaction.

“I was leaving the next day for my own recurrent training down in Orlando, at Pan Am SimCom. They have these different coffee breaks. I took the OPTICS survey along, and I used this control group, these other pilots that were there from different companies. Within about two weeks after that, we launched this OPTICS survey. It’s been one of our most popular surveys.”

Who gets Pro Pilot?

You don’t have to be a professional pilot to receive Pro Pilot, but if you aren’t one, you have to meet certain criteria.

“You could be a non-pilot who owns and operates a flight department,” Smith said. “You could be a CEO, president or general manager of a flight department. Some aviation department managers are no longer flying. Duane Futch has 28 airplanes now, and he doesn’t have time to fly anymore. You have a few like that. In other words, they’re in control of that flight department, so they still get it.”

The first step to getting on the mailing list is to fill out a card that says, “Tell us a little bit about yourself.”

“If it looks like you’re qualified, we’ll send you a demographic profile form, which is a very complete form,” Smith said. “If you’re flying a Cessna 172, you never get anything else. You need to be flying some serious turbine-powered equipment. If you come back with, ‘I’m the aviation department manager of XYZ Corporation, and we have two King Airs, a Beechjet and a Cessna Citation X, and we fly 450 hours a year,’ you’re qualified. You get the magazines; you fit the category in the BPA circulation form.”

In fact, Smith helped start the matrixes in Business Publications Audit of Circulation, which others now use.

“I studied BPA and ABC (Audit Bureau Circulation) and all that in college, where a lot of these other guys didn’t,” Smith said. “At the Leo Burnett Advertising Agency, I worked with circulation, so I’m very much up on circulation and circulation houses. I have a very clean circulation statement.”

Although the magazine’s circulation was recently at 39,000, Smith says it’s presently about 35,000, after some recent “housecleaning.”

“We’re not after commuter regional anymore,” he said. “It’s not a viable area. You won’t see advertisements for them in general aviation magazines. I hate to say it, but we’re getting rid of some airline pilots and commuter pilots. It’s sad to say, but they don’t buy anything.”

Smith explained that civil aviation in its entirety is based on three areas of Federal Air Regulations.

“General aviation is if you own an airplane and you fly it under Federal Air Regulation Part 91,” he said. “My Baron is governed by Part 91; so are the Citation X and the Gulfstream. If you have your airplane for hire, if you’re air taxi or charter, you’re under Federal Air Regulation Part 135. That’s still of interest to us.

“There are very few airlines that are under 135. Most airlines now are under Part 121. Talking about evolving, it used to be that we were very interested in this group because there were these very adventurous, pioneering guys who started these airlines. They sold the tickets, they carried the bags, and they flew the airplanes. They bought airplanes. But they’re gone now. All these people have sold out to the major airlines. Major airline buying is done by committee—by green-eye-shade people. We’ve gotten disinterested in it. So, I’m not renewing the subscriptions for these people. That’s made a dent in our circulation.”

Up close and honest

At Pro Pilot, Smith works closely with his wife of 14 years, Marcia Eleni Smith, whose title is assistant to the publisher. They met at a Latin American party in the Washington area. At that time, the Spanish he had learned earlier in Key West came in handy.

The man who seems to be an open book honestly reveals that this is his third marriage.

“I married a girl early, and that didn’t work out,” he said. “Then, I ended up with another one who was working for the attorney that arranged the divorce of the first one. She had come from France and was burping his babies and stirring things in a pot. I said, ‘Ahhh, that’s for me,’ because the first one didn’t want to have any kids. But after we had two kids, she ran off with one of my photographers in my Mercedes.”

Smith raised their two boys, Alex and David, who are now 26 and 23. Although he started them both off flying at an early age, they haven’t displayed his interest in that area.

“I flew Alex when he was six weeks old,” Smith said. “I took him all the way to the West Coast. I didn’t wait that long with David. I flew him when he was three weeks old. I flew them everywhere. Maybe they got bored; neither one has become a pilot.”

David is now in Osaka, Japan, studying robotics and computers and nanotechnology at the University of Osaka as an exchange student. Alex is at the University of New Orleans, studying computer science.

“Who knows, they might be interested later on, but at this point in time, they’re not,” he said. “I’m not pushing them to come into this.”

Although Smith’s love for aviation hasn’t rubbed off on his sons, he did pass it on to some of the students he had when he taught aviation at a local high school. He’s pleased when those past students come to visit him, and update him on their progress.

“It’s very nice,” he said. “I enjoy that a great deal. Just before the NBAA convention, I had lunch with two absolutely great students. One became a Navy pilot. I helped the other guy get a job with Mesa; he came from Ghana. He worked his tail off, became a U.S. citizen, and was a straight A student in my class. Now he’s flying right seat on an Embraer 145.”

When asked if he regrets not remaining a teacher, he shakes his head no. He also has no regrets about not following up on other interests. For instance, back in college, his talent in the area of dramatic arts temporarily caused him to ponder how he’d do in Hollywood. Now, he talks about admiring talented people like Director Sydney Pollack and composers like Burt Bacharach, but says he’s perfectly content just where he is.

“I look at Las Vegas sometimes, at some of these things done by fantastically talented people,” he said. “I never did that. I live well, and I fly around in my airplanes. I made this little book here. I do this little teeny corner, this little niche industry. I like the competition. I like going to NBAA, or going to see the advertisers or the editorial people. It’s a lot of fun. I love what I do here.”