By Jeff Mattoon

Millions of people find their identity in what they “do.” Musicians, actors, football players, artists—the list is endless. For the thousands of those people who suddenly find themselves paralyzed, in their view, life is over, because they can no longer do what made them happy. That isn’t the case with Rick Carpenter.

When 24-year-old Rick Carpenter woke up on a summer day in 1989, he had no idea that his world would completely change forever. In a freak accident in his bedroom, he crashed to the floor breaking his neck.

“The pain was unbelievable and that’s all I could think about for about 30 seconds before I blacked out. I remember yelling at my roommate to pull my neck and then I was out. I had a blip (of memory) in the ambulance and a blip in the hospital, but that’s all I remembered for about a month,” says Carpenter.

Doctors told Carpenter he’d never walk again. As he lay in the bed, inside he knew that the doctors were wrong. He had doctors and lawyers in his family and heard plenty of times how often their initial assessment wasn’t correct. Carpenter was sure that he just hadn’t talked to the right physician who would accurately diagnose him.

Within a matter of weeks, Carpenter and his parents decided to relocate him to Craig Hospital in Denver, arguably the nation’s best facility for the treatment and rehabilitation of spinal cord injuries. It was at Craig that Carpenter came to a full realization of his injury.

“Of course, I was angry at the situation, but it wasn’t until I got to Craig that I really decided how to feel about the whole thing, because there I had a number of people who were experts in the field to talk to,” he remembers. “It wasn’t until I got there that things began to hit home.”

Rick Carpenter’s reality would now include the word quadriplegic. He spent four months at Craig before returning home to Connecticut to live with his parents, but that didn’t last long.

Anger: the motivator

He arrived in Connecticut in February and by the fall of the year was back in school. Within a short time he moved west, this time to Los Angeles to attend the USC film school. After graduating, he went on to Loyola Marymount University to get his MBA.

It would be easy to assume his strong character is what caused Carpenter to get back on track, but as he puts it, “It’s amazing what a strong motivator anger is.” For a couple of years, anger is what moved him along. Carpenter’s anger never really showed on the outside; it was mostly something he dealt with internally, but he eventually “mellowed,” realizing that he didn’t want to lead an angry life.

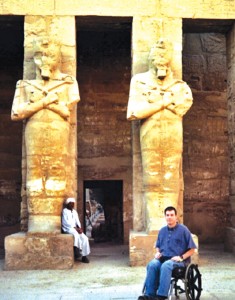

Rick Carpenter, now 40, works as a freelance writer in Hollywood, hoping to eventually write and produce his own sitcoms. Over the past 16 years, he’s traveled the world, visiting five continents enjoying an adventurous lifestyle. Arguably, Carpenter’s identity is related to his sense of adventure, and fortunately he gets many opportunities to scratch that itch.

Traveling has brought much joy to Carpenter, and as with all things in life you have to take the bad with the good. Through his travels, he’s been dropped, cut, argued with and had important things lost. However, in return, he’s received free travel and free upgrades to presidential suites because none of the other rooms had wheelchair accessible bathrooms.

He’s skied (didn’t like the experience too well—it wasn’t enough like it was before the accident), sky dived (in contrast, it was very much the same experience), scuba dived (it, too was very much the same experience) and, off and on, flirts with aviation.

Carpenter eventually would like to earn his private pilot’s license, but for now the budget doesn’t allow for it.

Rick Carpenter on the road in Egypt. Carpenter has been to five continents where there is plenty of satiation for his love of travel and adventure.

If you have the same questions as this writer, you might wonder how a quadriplegic could possibly earn his pilot’s ticket. Carpenter had the same thought process until he read an article in New Mobility magazine, a publication devoted to those who must utilize wheelchairs.

The article mentioned International Wheelchair Aviators, an organization devoted to assisting the wheelchair-bound and the disabled in obtaining their pilot’s license and subsequent ratings. This piqued Carpenter’s interest in flying—something he enjoyed briefly as a child.

A night out with dad

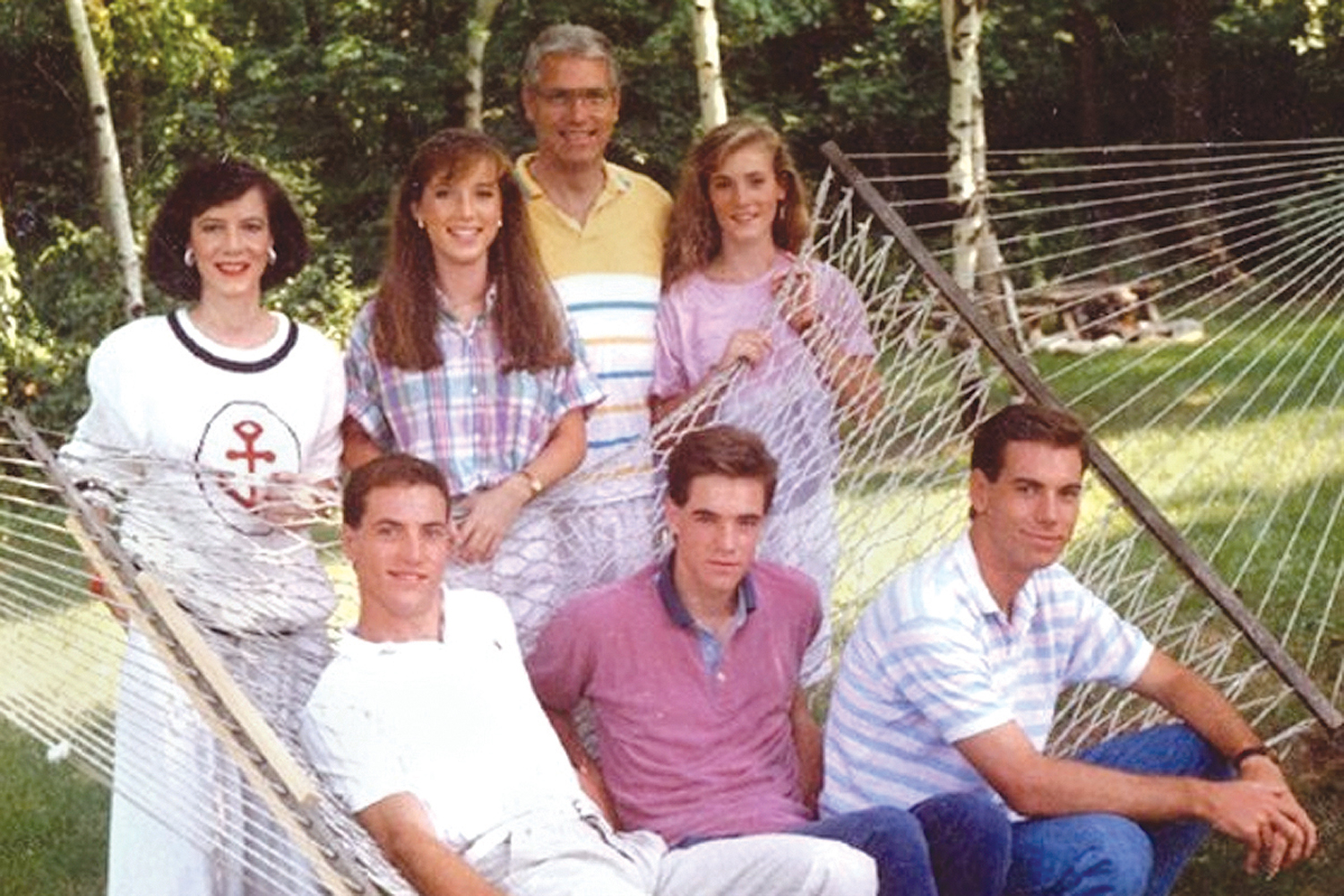

With four brothers and sisters, one-on-one time was at a premium with his parents. His father offered the children a regular night out with dad and while Carpenter’s siblings chose predictable activities like ice cream, ball games and the like, he chose for his dad to take him to a nearby general aviation airport to watch the planes take off and land.

One day, when he was about 14, Carpenter’s dad encouraged him to talk to a pilot who had just landed to see if he could sit in the airplane. His request was granted and that led to many flights with the newfound pilot friend.

Carpenter’s flying activities lasted about a year before the family moved out of state, away from an airport and with not enough money to take lessons anyway. Carpenter knew this because he asked numerous times and the answer was always “no.”

As he grew older, the urge to fly dwindled until he read about the IWA.

Mike Smith, president of the organization, is himself a wheelchair-bound aviator who was among the first disabled pilots to receive a second class medical certificate and actually makes his living flying.

Smith, a Vietnam helicopter pilot, broke his back in a crop-dusting helicopter accident in Palm Sprigs, Calif., in 1981. Without the use of his legs, his flying days were over—only for a short time as Carpenter would discover.

“I went back to school, got another degree and became the director of a brain injury department for a hospital. That lasted a couple of years when I found out through the California Wheelchair Aviators that hand controls existed. When I found that out, I quit all my jobs and went back into flying for a living,” remembers Smith.

At the time there were very few, if any, wheelchair aviators who flew for a living, but he was determined to get back to the job he loved. When the dust settled, he was not only allowed to fly, but he also received all his ratings back (IFR, multi-engine & CFI) and ultimately received a Part 135 approval.

Now Mike Smith owns and operates Pacific Crest Aviation in Big Bear, Calif., an aviation charter and flight school operation with three turbo-charged, twin-inline Cessna Sky Masters and a Piper Cherokee 180.

All of his pilots are able-bodied and Smith is the one to give them all their check rides. Eight months out of the year, things operate as a regular Part 135 on-demand air carrier, offering air-taxi service, scenic flights and flight training, but four months out of the year, in the summer, his company is virtually owned by the government.

Pacific Crest Aviation has contracts with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forestry Service during fire season to provide air support for forest fires, which gives Smith the opportunity to fly for pay all year long.

While Smith’s disability is no fun, he has fun with it.

“All of the pilots that work for me are ‘walkies’ and most of them are retired airline or freighter pilots. I’m the one in the wheelchair and I give them all their check rides!” he laughs.

Bill Blackwood, trail blazer

Son of a twenties-era barnstormer, Bill Blackwood became a naval aviator in the mid-forties, amassing some 5,000 hours. In the early sixties, Blackwood found himself and a student pilot in an uncontrollable inverted spin in a jet trainer. Sitting in improper form, his spine couldn’t endure the multiple G forces from the ensuing ejection, leaving his legs lifeless in an instant.

In the mid-sixties, Blackwood, inspired by another paraplegic, created the first portable aircraft hand controls and in a few short years had started the CWA, which decades later he renamed International Wheelchair Aviators.

It was information from the IWA that lead Mike Smith to the same realization that he didn’t have to give up his life’s passion. Smith eventually took the reigns from Bill Blackwood at the IWA, and continues the tradition of inspiring disabled aviators, and those who are disabled, aspiring to be aviators. The organization now boasts over 200 members worldwide with a whole host of disabilities represented.

Like everyone, the disabled must pass a standard FAA medical, where each case is forwarded to Oklahoma City for review. When the medical certificate is approved, it’s issued with stated restrictions. The most common restriction is the required use of hand controls. Once hand controls and any other device specified in the medical certificate are in place, an FAA examiner completes a statement of demonstrated ability, and the person is off to become a pilot.

These are the things Rick Carpenter has to look forward to when he decides to add “pilot” to the list of self-descriptors. Fortunately for him and thousands like him, others have blazed the rugged trail and found a good way to go.

For now, however, Carpenter has to deal with all the realities of life and learning to fly. His 12-year-old special-needs van has needs of its own—like replacement, and although he’s working on it, Carpenter hasn’t sold that high-concept script to Hollywood yet.

Someday, however, hopefully soon, you’ll pass a guy in a wheelchair on the tarmac with a huge smile on his face because he’s just earned his private. You’ll have no idea why, because your first thought most likely won’t be “wheelchair aviator,” but then again, you just might remember the IWA and think “Way to go, guy!, Welcome to the club.”

For more information on the IWA, visit [http://www.wheelchairaviators.org]. For more information on Pacific Crest Aviation, visit [http://www.pacificcrestaviation.com].