By Henry M. Holden

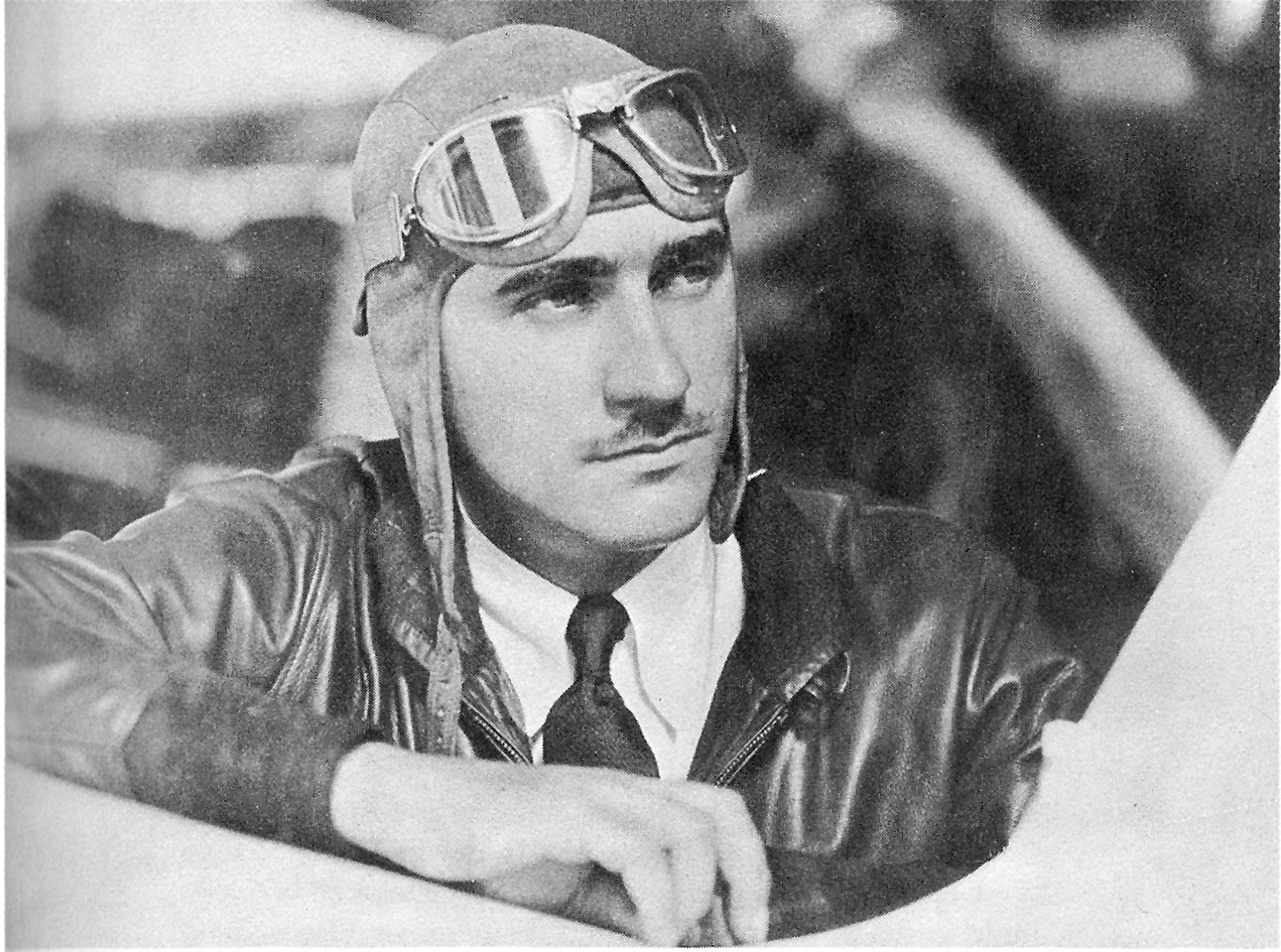

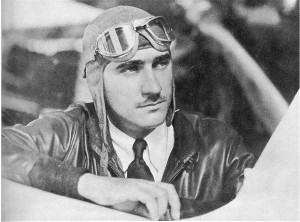

Paul Mantz, undoubtedly the most famous stunt flier in Hollywood history, earned more than $10 million during his career. Tragically, the way he died has often overshadowed his tremendous story.

It wasn’t easy for Paul Mantz to become a Hollywood stunt pilot, but when he did, he quickly mastered the craft.

Born Albert Paul Mantz on Aug. 9, 1903, in Alameda, Calif., but grew up in Redwood City. In 1914, when he was 11, he fashioned a pair of canvas wings that he hoped would help him to fly—from his tree house. However, when his mother spotted him, and shouted for him to come down and deliver his papers, his “solo” had to be postponed.

In 1918, his father died of a heart attack. His mother went back to teaching school for a living, and Mantz began taking odd jobs to help. On a windy March day, he waited to see Lincoln Beachey make his first public flight in a new yellow-and-silver monoplane, a Curtiss pusher called the Lincoln Beachey Special. After Beachey rolled his ship over and was descending from 6,000 feet, to do his trademark “Dive of Death,” with which he closed his shows, a wing snapped, and Beachey plunged in the Bay.

Although his death had shocked the young Mantz, his enthusiasm for the sky returned while watching another pilot perform at night, shooting Roman candles off from the cockpit of a Jenny. On his sixteenth birthday, Mantz took his first flying lesson. He paid for the instruction with money he’d earned driving a hearse for the local undertaker during the great influenza epidemic of 1919. At five dollars a body, he picked up $50 in two days.

Tragically, on the day he was to solo, his instructor put his Jenny through a series of graceful aerobatics above the field, but ended with a controlled spin that suddenly went flat. He crashed and died, as Mantz watched. Mantz drove the body to the undertakers, and for the next five years forgot about flying.

On Sept. 24, 1924, Mantz, 21, once again resumed his affair with the sky. With a friend, he was on his way to join thousands of San Franciscans at Crissy Field, to give a hero’s welcome to the Army’s round-the-world fliers, who were nearing the end of their global journal in three Douglas World Cruisers, the “New York,” the “Chicago” and the “Boston II.”

Suddenly, an aircraft spiraled down from the sky, its propeller motionless. The “Boston II” banked around into a forward slip and dropped down behind a row of tall eucalyptus trees to land. Lieutenant Leigh Wade, who had helped sink the German battleship “Ostfriesland” off the Virginia Capes in 1921, to prove the superiority of airpower over sea power, approached Mantz, and explained that his battery had gone dead and the engine had quit. He had no spare battery, and he wasn’t likely to find one.

Mantz told him that he knew where one was, and 30 minutes later, he was helping Wade install it. As a thank you, Wade scribbled a note (on a leaf of his logbook) that would get him on the flight line at Crissy Field, and gain him entrance to the operations building, for a close up look at the three DWC biplanes and half a dozen Curtiss pursuit aircraft; Mantz was impressed with the PW-8s, America’s first-line fighter planes.

Later, at the request of Wade, Mantz went to operations, where Major Delos C. Emmons, Crissy Field’s commanding officer, listened politely as Wade related how Mantz’ quick thinking had saved the honor of the world flight by getting the “Boston II” on her way before dark. When Emmons told Mantz that the Air Service could use men like him, interested in mechanics and flying, Mantz said he’d give it some thought.

R to L: Clark Gable and his wife, Carole Lombard, were close friends of Paul Mantz. They frequently went on hunting trips with him to Baja California, Utah and Montana.

However, he wasn’t impressed when, in answer to his question on how much a military pilot makes, he was told $250 a month.

“The big thing is we fly the hottest ships in the world!” Emmons said.

The highlight of Mantz’ visit was a ride in a Curtiss pursuit ship. Another unforgettable experience was meeting Captain William C. Ocker, who had made the world’s first long-distance blind flight, from Washington, D.C., to New Philadelphia, Ohio, with only a Sperry gyro horizon to tell him when he was flying straight and level.

In late May 1927, Mantz wrote a letter to Ocker, saying he’d decided to join the Air Corps, and asking whom he should see. A few days later, Ocker wrote him saying they would be happy to process his application for flying cadet training, and told him to send his college information, showing satisfactory completion of at least two years. Although Mantz had never attended college, a few days later, Ocker received a special delivery letter, written on university stationary, showing his “forged” record at Stanford University. Ocker called Mantz immediately to report for his physical.

With eight hours of dual flight time under his belt already, Aviation Cadet Albert Mantz stepped off the bus at Riverside in November 1927. After a month of basic training at March Field, on Dec. 1, 1927, he soloed, in the PT-1. By June 6, 1928, the day before graduation, Aviation Cadet Mantz, high on the list of honor cadets, had logged 58 hours dual and another 68 hours of solo time, and had finished his blind flying course in the hooded Link trainer.

On that day, with one hour of solo time to complete, he took off through San Gorgonio Pass, following the railroad. He had been over the same region on his cross-country checkout, and his instructor had told him what to do if he got lost: buzz a railroad station, and read the name of the town.

At Whitewater Station, he saw a train puffing up the grade. He rolled inverted and pulled down through a screaming Split-S dive, plunging the PT-1 earthward, before easing out of the dive and heading down the tracks, inches above the rails, toward the oncoming train. When the engineer whistled in alarm, Mantz zoomed up and over the locomotive, missing the stack by inches, and then slow-rolled past the station, waggling his wings as waiting passengers dove for the ground.

When he returned to March Field, Mantz found himself under arrest. He appeared before the disciplinary board, and was dismissed. He had picked the wrong train; it had been carrying VIPs headed for March Field, and the graduation.

Once home, Mantz found a letter from Captain Wade, who was now working for Consolidated Aircraft Corporation in Buffalo, N.Y., which manufactured the Fleet, an acrobatic sports plane. The letter said they were looking for a West Coast distributor. Mantz took on the Fleet distributorship, moving it to the Palo Alto School of Aviation, on the Stanford campus. The following year, on Jan. 26, 1930, Norman Arthur Goddard, the school’s founder and a former Navy flight instructor, died while flying a home-built glider.

Left in charge of the flight school, Mantz moved the operation to nearby Palo Alto Municipal Airport. Goddard’s widow, Phyllis May Goddard, later married one of the school’s flight instructors, who took over the bulk of the instruction work, leaving Mantz free to sell Fleets and fly charter trips down the coast to Los Angeles.

On one trip to Burbank, Mantz noted all the movie flying activity at United Airport. Knowing that Hollywood stunt pilots earned big money, by holding a monopoly that forced studios to pay them fat wages, he set his heart on that career. However, to become a Hollywood pilot you had to join the Motion Picture Pilots Association—and you couldn’t join the union unless you were employed in the movie industry.

Mantz came up with a plan. He gained attention by performing a record number of outside loops, after redesigning his Fleet demonstrator’s carburetor. On July 6, 1930, he more than doubled Tex Rankin’s record of 19; he performed an astounding 46.

Mantz also studied the industry, and realized that Hollywood studios were complaining that the MPPA was extorting exorbitant sums for slipshod flying. Also, if they were out of camera range, or if a flight was canceled because of mechanical or weather problems, the pilots were still paid. He also noted that within the union, fierce competition among the pilots was causing dissension and jealousy, weakening its strength. It was a chink in the armor that Mantz would attack.

He came up with a plan to offer the studios a smooth-running organization they could depend on, with a team of sharp pilots, first-class planes, a base of operations, an overhaul shop, and an insurance plan to protect the studios against costly delays. In short, he would offer them a “Hollywood air force.”

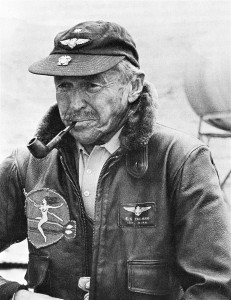

In 1961, Frank Tallman (shown) and Paul Mantz formed Tallmantz Aviation, a new stunt flying operation, to supply their Movieland of the Air Museum with a combined fleet of working aircraft.

Since that would cost a lot of money, and Mantz was broke, he made the rounds of the studios every day, looking for work. Without an MPPA card, he couldn’t get past the casting offices. Then he heard about a job none of the others had bid on—a $100 stunt for a scene in “The Galloping Ghost,” a film based on the life of football hero Red Grange. He couldn’t understand why nobody wanted it; all that was required was to fly low past a ground camera with a stuntman on the top wing.

Mantz confronted Frank Clarke, the president of the MPPA and the undisputed king of the Hollywood stunt pilots, and was told that the fee to join the union had just been raised from $10 to $100. Pancho Barnes, who formed the union, advised him to do it, although he would just break even on the job. He would be finally on the inside; now he could begin making money.

At United Airport, Mantz formed United Air Services, Limited, beginning with his Fleet demonstrator, a three-place Stearman camera ship and his red-and-white Travel Air stunt plane. He also arranged for the use of other ships he charged friends to hangar there. Although he sent out fliers to all the studios advertising rental of his ships and a highly trained crew, and although the other pilots from the MPPA soon began hanging out there, Mantz still did more charter work than stunt flying, until he pulled off a particularly difficult stunt nobody wanted for “Air Mail.”

The calls now began coming in. Some were from young women, wanting to take lessons from the dashing stunt pilot. One student was a girl named Myrtle he would marry on May 2, 1932. But Mantz was dedicated to his career, and it didn’t help that his work meant associations with glamorous women; the marriage ended in divorce four years later.

One name that would come up during divorce proceedings was that of Amelia Earhart. On the stand, Mantz testified that his relationship with Earhart, who had been a house guest of the couple on two occasions and who was married to George Putnam, was that she employed him as a technical adviser for her flights, and had bought some stock in his company.

As technical advisor for Earhart, Mantz contributed his expertise to meticulously planning her pioneering flights. Sadly, to cut weight, she insisted on removing his long-range radio on her last flight. A year after his divorce, Mantz would mourn the loss of his friend and employer, when she disappeared near Howland Island, on July 2, 1937, while attempting a round-the-world flight.

The Honeymoon Express, war and air racing

Motion picture flying, charter flying, forest patrol work and air ambulance flights filled Mantz’ days. His charter service was popular with the Hollywood crowd, and his legendary “Honeymoon Express” was in almost continual use by stars heading for Las Vegas marriage chapels. As for Mantz, he took the plunge again himself one more time, marrying Terry Minor, with whom he would produce Paul Jr., born in 1938.

Through most of 1941, Mantz’ efforts went into making war films. For Warner Brothers, he flew aerial scenes for “International Squadron,” “Dive Bomber” and “Captains of the Clouds.” MGM called him to make “Stand By for Action” and “Flight Command.” Republic needed him for “Flying Tigers,” Paramount for “I Wanted Wings,” Universal for “Flying Cadets” and Fox for “A Yank in the RAF.” Pearl Harbor ended his lucrative commercial work.

Then, as a colonel in the USAAF’ First Motion Picture Unit (“Hollywood’s Army”), during WWII, Mantz produced training films for aviation cadets and morale-boosting films for the public, with his team of soldier-actors that included Clark Gable, Alan Ladd, Ronald Reagan and George Montgomery.

Following the war, Paul Mantz Air Service handled tasks including flying daily film rushes into Hollywood from distant locations. In 1946, he invested $55,000 in 475 surplus bombers and fighters, much to the amusement of his friends. At the time, it was the world’s sixth largest air force. The fleet of surplus had cost the American taxpayers $117,000,000.

Mantz ended up bringing a dozen of the best ships to Burbank. His partners in the deal disposed of the rest of the fleet for scrap. First, however, they drained the fuel tanks; the fuel alone sold for more than he had paid for the entire fleet. Then, Mantz netted $160,000 worth of scrap aluminum, $100,000 worth of Plexiglas, more than 1,000 good engines, and a warehouse full of 6004-A oxygen regulators that an embarrassed U.S. government bought back, at $75 each, for their own postwar airplane fleet.

When 20th Century Fox needed a special aircraft for “The Flight of the Phoenix,” Otto Timm designed the Tallmantz Phoenix P-1 for Tallmantz Aviation Inc.

Mantz had his chief mechanic, Cort Johnson, strip down three of the aircraft, two Mustangs and a B-25 Mitchell bomber, and rebuild them. The B-25 would come to be known as “The Smasher.” Mantz would use it as his personal aerial camera ship.

Mantz came in third in the 1938 and 1939 Bendix races with his Lockheed Orion. When the races resumed after the war, he had three consecutive Bendix wins. In 1946, he flew the Van Nuys, Calif.-to-Cleveland speed run at 435.5 mph in 4 hours and 42 minutes, in one of his surplus Mustangs. The next year, he flew the same bright red P-51C, christened “Blazing Noon,” in 4 hours and 27 minutes, at an average speed of 460.42 mph. In 1948, he flew the other surplus P-51 to Bendix glory in 4 hours and 34 minutes, at an average speed of 447.98 mph. His Bendix preeminence ended only days before the 1949 race, when he dropped out to “give someone else a chance.”

By the late 1950s, although Mantz was still Hollywood’s leading individual stunt pilot, he joined forces with another outstanding stunt flier, Frank Tallman. In 1961, at Orange County Airport, they formed Tallmantz Aviation, a new stunt flying operation, to supply their Movieland of the Air Museum with a combined fleet of working aircraft. But the collaboration didn’t last long.

In a 1965 interview with Don Dwiggins, who would eventually write “Hollywood Pilot: The Biography of Paul Mantz” (1967), Mantz said he knew he was supposed to be “a devil-may-care aviator,” and that he’d done his share of “roaring under bridges, flying through open hangars and deliberately crashing planes,” but that he wasn’t a “stunt pilot.”

“I’m a precision flier, and I’m alive today to prove it,” he said.

He had also often said that if he ever “cracked up,” it would be in a car, not in a plane. However, that wouldn’t be the case.

Twentieth Century-Fox needed a special aircraft for “The Flight of the Phoenix,” a film starring Jimmy Stewart as the pilot of an aircraft that crashes in the Sahara, and then has to supervise the survivors in designing a flyable plane from the wreckage. Otto Timm designed the Tallmantz Phoenix P-1, the plane that would arise from the wreckage of the C-82, for Tallmantz Aviation Inc. The plane was built with wings from a twin-engine Beech C-45 and a 550-hp P&W R-1340 engine from a T-6. The complete rear fuselage and tail were wood with a plywood covering. For the purpose of the film, the main wheels had to be concealed to give the impression of it taking off on make-shift skids. The airplane was purposely made to look flimsy, but it passed an FAA inspection.

Initially, Tallman was supposed to fly the P-1 in a landing sequence in Buttercup Valley, in the Arizona desert, but he shattered his kneecap during a fall at home. On July 8, 1965, Mantz, 62, came out of semi-retirement to take his place.

Mantz flew the P-1 several times, learning what it could do, and would not do. Bobby Rose, a longtime Hollywood stuntman, was in the seat behind Mantz. The plane wasn’t capable of taking off from the sand, so they would concentrate on filming the latter part of a touch and go. The first pass went well, but the director wanted a second pass for “insurance.”

As the plane touched down, the wheels struck a small sandy hump of sun-baked dirt that started to drag heavily at the undercarriage. Mantz gave the engine full throttle, and the plane broke free of the sand. It traveled about a hundred yards with Mantz pulling back on the stick. However, the bump had broken the back of the aircraft, and it split in two, tumbling over at 90 mph on the desert floor, breaking up in the process.

Mantz died instantly when the engine crushed him. Rose, standing behind in the rear of the makeshift cockpit, had strapped himself to a stringer. He was able to release the belt and kick free of the plane. He broke his shoulder blade, but survived and eventually flew again.

When the NTSB accident report was later released, it cited pilot error, stating “pilot-in-command misjudged altitude…airframe overload failure…and alcoholic impairment and judgment.” It’s hard to understand today, but Mantz drank when he flew—and judging by his performances, was still a good stick.

A pilot can always stay out of trouble, he contended, if he uses his head, plans his flight carefully, and avoids letting one emergency compound another. Often, he had made forced landings in small fields when engine trouble occurred. They weren’t a matter of luck; Mantz, like any good pilot, constantly scanned every potential landing field, just in case. However, this was an accident Mantz had not foreseen, brought on because the aircraft couldn’t handle the stress of its takeoffs and landings on asphalt. The landings probably contributed to the fatigue of the airframe. The weather also wasn’t ideal; the temperature was well over 120 degrees and the airplane was sluggish, lacking the lift that arguably may not have helped get the craft out of its trouble.

A few days after Mantz’ death, Tallman faced his own individual tragedy when doctors amputated his leg because of a massive infection that had resulted from his broken kneecap. Despite the loss of his leg, and his close friend, Tallman retrained himself to fly using only one leg, and returned to stunt flying. Later, he worked on such films as “The Blue Max,” “Catch 22” and “The Great Waldo Pepper.” On April 15, 1978, Tallman, age 58, died in a crash after failing to clear a ridge near Palm Springs, Calif., due to poor visibility.