|

A few years ago, Brig. Gen. Paul W. Tibbets Jr. talked to Airport Journals about one of the most momentous occasions in his life. It was a “bombing run,” but it wasn’t the one most people equate with Tibbets’ name when they hear of the 92-year-old’s death, on Nov. 1, 2007, after months of failing health. As he reminisced, Tibbets recalled that it was a perfect day for his important mission. He hadn’t slept much the night before, thinking about what was ahead. His father, Paul Warfield Tibbets, owned a wholesale confectionary business and was the area distributor for Curtiss Candy. Curtiss had a new candy bar, the “Baby Ruth,” and Doug Davis had a plan to promote it. “He was an entrepreneur who was always trying to figure an angle for an airplane to play a part,” Tibbets recalled. “He sold Curtiss on the idea of dropping those candy bars from an airplane over large gatherings of people.” When young Tibbets hear the plan, the only thing the 12-year-old could think of was being up in that biplane, throwing out those candy bars. In 1978, Tibbets penned “The Tibbets Story” (updated as “Enola Gay” in 1998), recalling his excitement as Davis arrived in his Waco 9, wearing the typical barnstorming apparel of the day: leather jacket and helmet, whipcord breeches and goggles. Young Tibbets fired off question after question, and eagerly listened to the answers: Yes, the aviator had looped the loop, many times. Yes, sometimes, a tailspin does make you dizzy. He pitched in to help warehouse workers attach a small paper parachute to each candy bar. Davis told the boy’s father that he would need somebody to throw the candy bars out of the front cockpit. “I volunteered right quick,” said Tibbets with a grin. “My old man looked at me and said, ‘Not you!’ Doug said, ‘Mr. Tibbets, I’m not going out there and kill myself, because I have a wife and two lovely daughters. I won’t hurt myself, and I’m not going to hurt him.’ My old man reluctantly said ‘OK.'” The next morning, when Tibbets arrived at the pasture, he couldn’t take his eyes off the Baby Ruth biplane. “It looked beautiful to me,” he said. He watched and waited as Davis prepared, wondering if they’d ever get in the air. |

|

“He was checking with me to be sure I had my safety belt on,” Tibbets said. “I kept thinking, ‘Gee whiz! Let’s get going. Let’s fly!’ Finally, he pushed the throttle forward, and we started across the ground. I said, ‘We’re not going very fast.’ About the same time, the airplane was off the ground.”

They arrived over the Hialeah racetrack at about 2 p.m. Davis flew around, letting people get a good look at the biplane, before they began throwing the candy bars.

“We exhausted that supply of candy bars in about 10 minutes,” Tibbets said.

Then it was back to the pasture for another load.

“Doug said, ‘Let’s go to Miami Beach and have some fun,'” Tibbets remembered. “I had the time of my life; he’d go up and down the beach, and I’d try to throw candy bars to the people running below us.”

That was the day he decided he would be a pilot.

“Nothing else would satisfy me, once I was given an exhilarating sample of the life of an airman,” said the man who, 18 years later, would pilot a bomber to Hiroshima “with a cargo of death instead of chocolates.”

Pre-candy bombing days

Paul W. Tibbets Jr. was born in Quincy, Ill., on Feb. 23, 1915, to Paul and Enola Gay Tibbets. Although Tibbets was too young to remember World War I, he remembered his father coming home in uniform, after serving overseas as a captain with the 33rd Infantry Division. The family moved quite a bit because of his father’s wholesale business.

On Aug. 5, 1945, Paul Tibbets piloted the B-29 Enola Gay to Hiroshima and dropped the world’s first atomic bomb. He later served in the Strategic Air Command, served a tour with NATO and established the National Military Command Center in the Pentagon.

When he was 3, the family moved from Quincy to Davenport, Iowa. A couple of years later, they bought a house in Des Moines. A trip to visit his mother in Miami in the winter of 1923 led Tibbets Sr. to relocate his family again.

“He departed Iowa in a snowstorm,” said Tibbets. “Once he saw Miami, he said, ‘There’s no damn reason to live in Iowa.’ We packed up and moved there.”

On visits to Iowa every summer to vacation on an uncle’s farm, Tibbets learned to farm, milk cows, shoot a rifle and shotgun and hunt rabbits and other small game.

In Miami, Tibbets Sr. and Bob Smith launched Tibbets and Smith, Wholesale Confectioners, which soon became the largest business of its kind in the state. In 1930, Tibbets Sr. moved his family back to Chicago, so he could help dispose of the family-owned grocery houses. Tibbets and Smith sold their confectionary business to a large Tampa cigar and tobacco firm. Four years later, the Tibbets family returned to Florida.

Schooling

In 1928, as an eighth grader, Tibbets entered Western Military Academy in North Alton, Ill. He graduated from the academy in June 1933. Before beginning the University of Florida that fall, he reacquainted himself with airplanes.

While traveling around Miami in a 1931 Chevrolet his grandmother had given him, he came across Sunny South Airport. As he looked around, a man asked if he could be of help.

“I said, ‘I’ve always wanted to fly,” Tibbets recalled. “He said, ‘We can put you in an airplane and start teaching you.'”

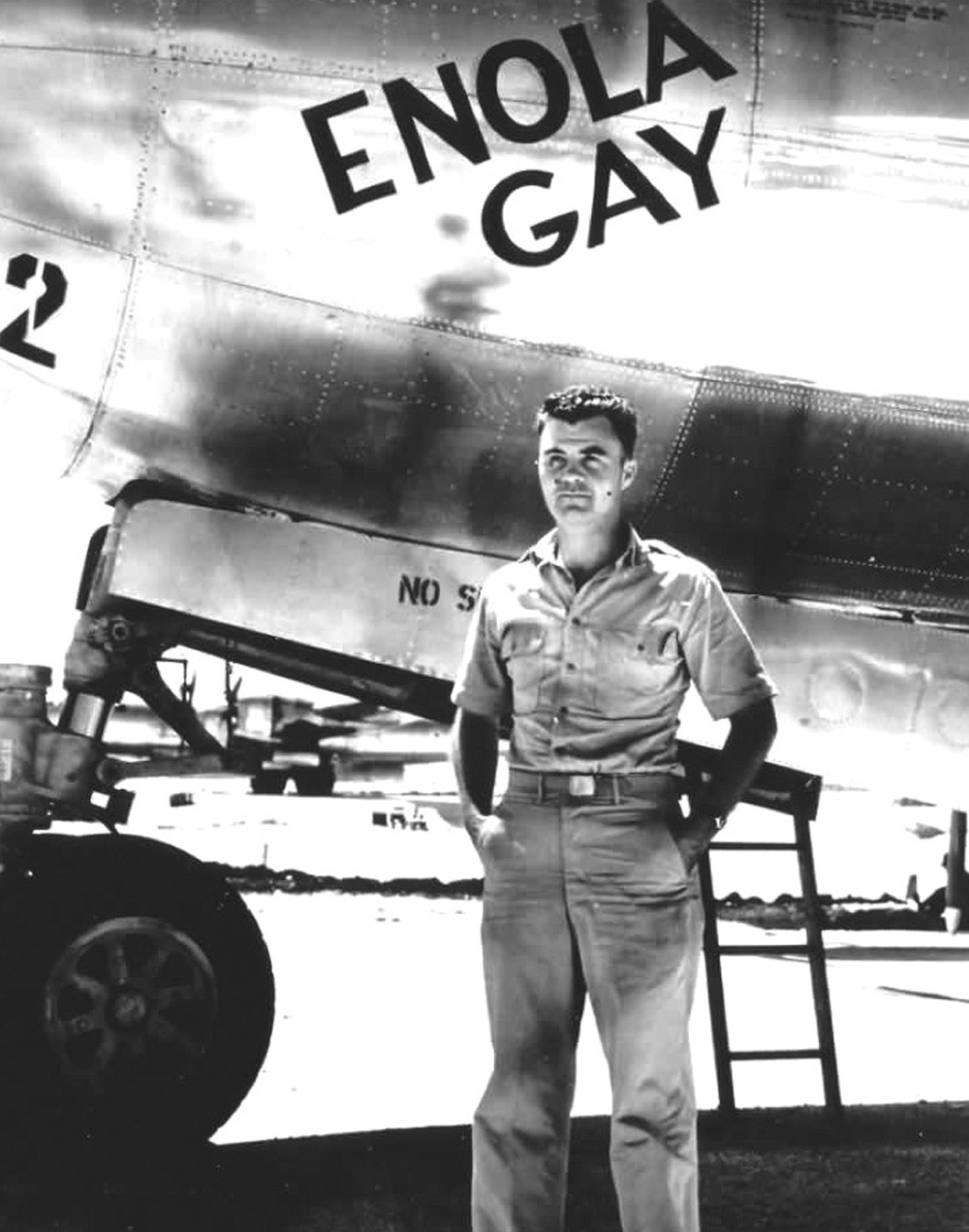

Shown at the age of 8, Paul Tibbets Jr. got his first taste of flying when he was 12. He knew instantly that he wanted to be a pilot.

Tibbets handed over the $7 required for 30 minutes of instruction.

“The man’s name was Rusty Heard; he was a Reserve naval mechanic and pilot,” Tibbets said. “We became real good friends. I flew with Rusty as regularly as I could.”

A busy summer prevented Tibbets from soloing, but he came back the next year, and with Heard’s help, became familiar with a Taylor Cub.

“I loved that thing, because you had to have some kind of a reference to keep the airplane flying level,” he said. “If I kept the second rib around the cylinder on the horizon, the airplane flew level.”

Tibbets’ first solo attempt almost ended in disaster.

“A Navy biplane zoomed straight in front of me,” Tibbets said. “I didn’t know what he was doing. Rusty was waving his arms and doing all kinds of things.”

Tibbets came in for a landing, and the two learned that the Navy pilot, a lieutenant commander in charge of operations at Opa-locka, was trying to get out of the way of a dirigible that was coming in.

“Rusty told me later, ‘He was trying to get word to you; that’s why he pulled in front of you,'” Tibbets remembered.

Decision time

Tibbets’ future had been decided years before he discovered his fascination for airplanes.

“My father told me, ‘There’s always been a doctor in the Tibbets outfit until I came along, but I didn’t even get a college degree. You’re going to be a doctor,'” he recalled.

Tibbets spent his first semester at the University of Florida going to dances and movies, parking along lonely roads around Gainesville with various female companions and playing poker. Over Christmas vacation in 1933, his dad laid down the rules.

“He made it clear that since he was paying the tuition, it was my job to see that he got his money’s worth,” Tibbets said.

Although his father’s confectionary business led to Paul Tibbets’ first flight, it was his mother, Enola Gay, who initially accepted his decision to be a pilot.

When Tibbets brought up his grades, his father awarded him with a new Airflow DeSoto. His sophomore year would be his last on that campus. His father enrolled him at the University of Cincinnati to complete his premed studies.

“The family had a number of doctor friends, several of whom had invited me to watch them at work,” he said.

Tibbets lived with the Crums, old friends of the Tibbets family. Dr. Alfred Harry Crum operated two clinics and was on the staff of a major Cincinnati hospital. Tibbets spent weekends working as an orderly in the hospital and often helped in the emergency room.

After a successful first year at the university, Tibbets realized his enthusiasm about a career in medicine had diminished. He had witnessed doctors not yet 50 die from heart attacks and other problems induced by hypertension and overwork and listened as Crum complained that the country was “drifting toward socialized medicine.” But the biggest reason for his change of heart was his growing infatuation with airplanes.

“When I got to Cincinnati, one of the first things I did was visit Lunken Field,” he said. “I wasn’t looking for any instruction at that time; I could take off and land. That’s all I needed to know.”

Sensing Tibbets’ interest in flying, Crum told him to follow his dreams. He considered a career in commercial aviation, but knew his father wasn’t likely to foot a training bill.

Just before Christmas, while flipping through a Popular Mechanics magazine, some words caught his attention: “Do you want to learn to fly?” The advertisement was for the Army Air Corps. Tibbets sent in an application to become a flying cadet before he headed home for the holidays. When his mother took the news well, he mustered the courage to tell his father.

“He said, ‘I think I’ve done pretty well by you so far, but it’s all finished today. If you want to go fly airplanes, go ahead. Kill yourself. I don’t give a damn,'” remembered Tibbets.

But his mother supported her son.

“Paul, if you want to fly, you go ahead,” Enola Gay Tibbets calmly said. “You’ll be all right.”

Shaping destiny

Although his father’s confectionary business led to Paul Tibbets’ first flight, it was his mother, Enola Gay, who initially accepted his decision to be a pilot.

Tibbets entered the Army Air Corps on Feb. 25, 1937, with his formal induction at Fort Thomas, Ky. When he did well during basic training at Randolph Field, San Antonio, Texas, he was given the choice of advanced training—pursuit or observation—at Kelly Field.

Tibbets leaned toward fast fighters or pursuit planes until a company tactical officer advised him that if he chose pursuit, someone else would be deciding where he went and how he got there. With observation, he’d be doing most of his flying alone and making his own decisions. That appealed to Tibbets’ “independent nature.” His decision would eventually lead to his “unanticipated rendezvous with history.”

Upon graduation from the advanced training program at Kelly Field, Tibbets, with 260 hours in his logbook, became a second lieutenant. Paul Tibbets Sr. attended the graduation ceremony in February 1938.

“He said, ‘After talking to these men that are teaching you to fly, I feel a whole lot better about it. I’m not going to worry anymore,'” Tibbets recalled.

Tibbets’ first assignment was to Flight B, 16th Observation Squadron, Lawson Field, Fort Benning, Columbus, Ga. Shortly after his arrival, a friend invited him on a double date. Tibbets’ date would be Lucy Wingate, from Columbus, whom he married in June 1938. In late 1940, Lucy gave birth to Paul Tibbets III.

Tibbets’ introduction to multi-engine aircraft was flying the B-10 twin-engine bomber. At Fort Benning, he was assigned to fly Lt. Col. George S. Patton’s two-place Stinson Voyageur. Patton had decided that an airplane would be a useful tool in developing tactics for the armored brigade he’d organize at Fort Benning. Patton had requested that the Pentagon authorize flight training and an airplane for his personal use, so he could be an “eye in the sky.” When his request was denied, he personally bought the Voyageur.

After Tibbets had gained 1,500 hours in the B-10, the Army Air Corps tapped him to join the 90th Squadron of the 3rd Attack Group at Hunter Air Force Base, Savannah, Ga. The first lieutenant was assigned as the squadron’s engineering officer.

Flying the new Douglas A-20 attack bomber would be an adjustment; instead of flying at high altitude, flight would be low and in tight formation. Reports out of Europe said that the Germans were building flak towers 100 feet above the ground. The American pilots’ orders were to fly no higher than that, operating below the fire from those installations, and using the natural terrain as a shield.

“I liked that very much,” Tibbets said. “It was really precision flying.”

What’s Orson Welles up to now?

In early December 1941, Capt. Tibbets received orders to join the 29th Bomb Group at MacDill Field, Tampa, Fla. He was to train in the new Boeing B-17, the four-engine “Flying Fortress.” Shortly after those orders came through, he flew to Fort Bragg, N.C., to conduct attack missions over ground troops as part of an Army maneuver. While flying back to Savannah, he heard an excited voice on the radio.

“He said, ‘We have just been notified that the Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor,'” Tibbets recalled. “I thought, ‘What the hell is Orson Welles up to this time?'”

When Tibbets returned, his operations officer said he needn’t worry about going to MacDill, because in a sense, MacDill was coming to him.

“He said, ‘They had orders to move all their airplanes to Savannah, because they’re afraid the Japanese will send a submarine up into Tampa Bay and start shooting MacDill,'” said Tibbets. “I thought, ‘That’s the most stupid thing in the world.’ I’ve been around water enough to know you don’t send a submarine into only 20 feet of water. But I learned that the Army had its way of doing things, and nothing was going to change that.”

Tibbets’ temporary duty was to form an antisubmarine patrol at Fort Bragg, Pope Field. He and other personnel would patrol from Cape May, N.J., to the Yucatan Channel, in 30 Douglas-built B-18 twin-engine bombers they ferried there. He said the B-18 wasn’t “worth a hoot” as a bomber, since it couldn’t carry much of a load and didn’t fly fast.

“But it was a wonderful airplane just to fly around in,” he said.

Once his temporary duty was over, Tibbets took command of the new 340th Bomb Squadron, 97th Bombardment Group, which was transitioning to the B-17 and moving to Sarasota, Fla. Orders eventually came in for Fresno, Calif. Tibbets assumed he and his squadron would be going to the Pacific, but they were told to report to Bangor, Maine, and would soon be on their way to England.

Movement of the 97th BG started in mid-June. The large-scale ferrying operation included 49 B-17s, as well as P-38s and C-47s.

Polebrook

Tibbets arrived at Polebrook, a short distance northeast of London, in early July. After Col. Frank Armstrong took over command of the base, he appointed Maj. Tibbets his executive officer. Tibbets said that operations were lax at Polebrook, but that soon changed under the “no nonsense” officer. Armstrong and his men would be fictionalized in “Twelve O’Clock High,” written by Beirne Lay Jr. and Sy Bartlett.

Tibbets made his first of 25 combat missions in the B-17 on Aug. 17, 1942. Eleven other aircraft

followed his lead, bombing railroad-marshaling yards at Rouen, near the Channel coast in northern France, in the first American Flying Fortress raid and initial daylight raid by an American squadron against German-occupied Europe.

Tibbets’ attack on Lille in October signified the first time Americans put more than 100 bombers in the air for one raid; B-24s of the newly operational 93rd Bomb Group and twin-tailed Liberators joined them.

In October 1942, Armstrong gave Lt. Col. Tibbets a special assignment. He would be flying Maj. Gen. Mark Clark to a rendezvous with the French, in preparation for the invasion of North Africa, known as “Operation Torch.” Upon his return from that trip, he would ferry Gen. Eisenhower to Gibraltar. Eisenhower would command the overall operation, Clark would serve as his deputy and Gen. Patton would lead the invasion troops at Casablanca. Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle was in charge of the air forces taking part in the invasion.

On Nov. 2, Tibbets flew from Polebrook to the aerodrome in Hurn, England, near Bournemouth, where he and the other pilots would meet the military leaders coming from London. When Eisenhower’s party arrived, weather had socked in the B-17s. The next day, conditions were even worse.

On Nov. 5, three days before the first scheduled landings in Africa, Tibbets was out on the flight line, in a steady rain and thick fog. It was beginning to look like they might not make it to Gibraltar by the time the parachutists were making their jumps for the invasion.

“Gen. Eisenhower was on my right and Jimmy Doolittle was on my left,” Tibbets recalled. “The weatherman said the weather wouldn’t break for a week. Eisenhower says, ‘Gen. Doolittle, what should we do?’ He says, ‘Ask Paul Tibbets; he’s flying the airplane, not me.’ I said, ‘General, I realize what I am taking in this airplane and how important it is to the success of this war. But if I didn’t have you, I’d have gone a long time ago!’ He said, ‘Let’s go. I got a war waiting on me.'”

After ferrying Clark to Algiers, Tibbets conducted bombardment missions in North Africa for several weeks, under direct control of the British, pending buildup of American bomber forces. With the arrival of the remainder of the 97th BG, he resumed normal combat operations in the Sahara Desert. In January 1943, he was reassigned to the Twelfth Air Force Headquarters at Algiers, where he would be Doolittle’s bombardment chief, reporting directly to Col. Lauris Norstad, chief of operations.

In February 1943, Doolittle called Tibbets into his office and told him about a request from Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army Air Force.

“He said, ‘Gen. Arnold wants my best field grade officer with the most experience in B-17s to come back to the United States. They’re building an airplane called the B-29, and they’re having a lot of trouble with it,'” Tibbets recalled.

Nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (left) converses with Col. Leslie Groves beside the remains of the tower used to set off the world’s first atomic explosion on the Alamogordo bombing range.

Tibbets was soon doing flight test work with the Boeing factory and Air Materiel Command. In March 1944, he transferred to Grand Island, Neb., as director of operations under Gen. Frank Armstrong, who started a B-29 instructor transition school.

Before he could settle into that job, he was ordered to the Army airfield at Alamogordo, N.M., to work with Dr. E.J. Workman, a University of New Mexico physics professor who had been involved in a theoretical study of the Superfortress’ vulnerability to fighter attack. Tibbets would be testing his theories in simulated combat.

The B-29 assigned to him for these tests was fully equipped, including a full complement of weapons and armor plating. However, when Tibbets arrived to work, he found that the plane was out of commission for at least 10 days. He decided to try flying a “skeleton” B-29, without any guns or armament.

With the aircraft 7,000 pounds lighter, Tibbets was amazed at how easily the plane handled and how high it could climb. He had a wonderful time with the attacking P-47s.

“They’d come in and do victory rolls and all kinds of things,” he said. “Finally I heard, ‘Tell him to slow down! I can’t catch him.’ I looked at my altimeter; instead of being at 25,000, I was at 31,000. I was on autopilot. I put that in the back of my head.”

A plan is unveiled

When Gen. Uzal G. Ent, commander of the 2nd Air Force, requested Tibbets attend a meeting with him in Colorado Springs, Colo., Tibbets was unaware of the tremendous assignment Ent had in store. On Sept. 1, 1944, he winged his way toward Colorado.

Upon Tibbets’ arrival, Lt. Col. Jack Lansdale ushered him into a meeting with Ent. During the conversation, Dr. Norman F. Ramsey, a former Columbia University professor, explained he was a nuclear physicist and that he and other scientists had been building weapons at a secret laboratory in Los Alamos, N.M.

“He said, ‘We’ll call them what they are; they’re atomic explosions,'” Tibbets recalled.

In the 1930s, the U.S. learned that German scientists had discovered how to fission the uranium atom, releasing nuclear energy. Many now feared that Hitler might acquire an atomic bomb. In the fall of 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt received a letter from famed physicist Albert Einstein regarding the possibility of developing an extremely powerful bomb, after Hungarian physicists and refugees Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner sought his help. In early October 1941, Roosevelt approved intensified research into the feasibility, although the decision to devote full energy to the bomb’s production wasn’t made until Dec. 6, 1941, the day before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Paul Tibbets’ knowledge of the B-29’s capabilities and limitations was one factor that led Gen. Uzal G. Ent, commander of the 2nd Air Force, to select him to organize and train a special unit to test-drop and later deliver atomic weapons.

In June 1942, Roosevelt transferred the project to the War Department’s Army Corps of Engineers. To disguise the secret project, the Corps created the Manhattan Engineer District, with headquarters initially in New York City.

Three months later, engineering officer Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves was appointed to head the Manhattan Project, which involved the expenditure of two billion dollars and the employment of more than 100,000 workers and scientists, in factories and laboratories scattered around the country. Most of the factory workers weren’t aware of what their labors would produce.

In late 1942, Groves chose nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who came to the project from the University of California, Berkeley, to head a new laboratory devoted to designing atomic bombs, one using uranium and the other plutonium. The Los Alamos laboratory opened in April 1943.

Now, someone was needed to organize and train a group to test-drop and later deliver those weapons. That person would also recommend and supervise required modifications of the aircraft involved.

Gen. Arnold had told Ent to select a leader to organize the special unit. Several factors determined Ent’s selection of Tibbets, including his knowledge of the B-29’s capabilities and limitations, as well as his demonstrated leadership and independence and his help in devising many of the bombing techniques successfully used in the air war.

During the meeting, Navy Capt. William Parsons, in charge of atomic bomb ballistics at the Los Alamos laboratory, detailed how shock waves would affect the bomb-carrying B-29 and discussed a new phenomenon known as radiation.

“I was listening with my ears wide open,” said Tibbets.

As the conversation neared its end, Ent told Tibbets that he would need to conceal the nature of his work from everyone, including his family and his coworkers. He also gave him some advice.

“He said, “You’re going to have a hell of a lot of responsibility dumped on you, but you have a lot of authority to go with it. Be careful how you use it,” Tibbets remembered.

The work begins

Tibbets began his work immediately, selecting Wendover Army Air Base, on the Utah/Nevada border, as the base for his “atomic air fleet,” which would be told only that they were working on a “special mission” that could end the war. Ent had suggested using the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, 504th Group, from Harvard, Neb., already training in B-29s, as the nucleus of the special air force. Tibbets added men of his own choosing, including former B-17 crewmembers Maj. Thomas W. Ferebee, bombardier; Capt. Theodore J. “Dutch” Van Kirk, navigator; Tech. Sgt. Wyatt E. Duzenbury, flight engineer; and Staff Sgt. George R. Caron, tail gunner.

Enola Gay crew, L to R, Lt. Col. John Porter, Capt. Dutch Van Kirk, Maj. Tom Ferebee, Col. Paul Tibbets, Capt. Bob Lewis, Lt. Jacob Beser. Sgt. Joseph Stiborik, SSgt. George Caron, Pfc. Richard Nelson, Sgt Robert Shumard and SSgt Wyatt Duzenbury kneeling.

Tibbets’ copilot would be Capt. Robert A. Lewis, who had been involved with him in B-29 testing. Of less than 50 people he chose by name, others included bombardier Kermit Beahan, navigator; and James van Pelt, radar specialist.

On Dec. 17, 1944, formal orders were issued activating the 509th Composite Group, later nicknamed “Tibbets’ Individual Air Force.” Tibbets soon became acquainted with the bombs in development: “Fat Man,” containing a sphere of plutonium, earned its name due to its bulbous, pumpkin-like shape; the more slender “Little Boy” utilized slugs of uranium.

As it became more evident that “Little Boy” would be the first used, scientists warned it would be unsafe to drop the 9,000-lb. bomb from an altitude of less than 30,000 feet. Calculations showed that the airplane needed to be at a distance of eight miles to withstand the shock wave caused at detonation. Scientists estimated that the shockwave could travel eight miles in 43 seconds; it would take the plane two minutes to cover the same distance. It would be Tibbets’ task to increase the distance between blast and bomber.

Recalling his work on the “skeleton” B-29 in Alamogordo, he decided the B-29 should be stripped of turrets and armor plating. The planes involved in the mission would also be fitted with fuel-injected engines and new technology reversible-pitch propellers.

Even before receiving requisitioned B-29s, pilots dropped practice bombs onto the desert. In the winter of 1944, Tibbets received permission to send crews over various islands, to practice the transition from over-water to over-land flying.

President Harry S. Truman, sworn in after the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, would come to believe that the atomic bomb would be the means of ending the war quickly, thus avoiding a costly invasion of Japan and preventing casualties on the scale of “an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.” An atomic bomb test was scheduled for July, but scientists quibbled over odds, adding to delays. Tired of waiting for word of his group’s move to the Pacific, Col. Tibbets took matters in his own hands.

“I had this number to call,” he said. “All I had to do is say, ‘Silver Plate’s ready to go.'”

Almost immediately, inspectors showed up and gave his men the OK. Members of the group were soon on their way to Tinian Island in the Marianas chain. The S.S. Cape Victory sailed on May 6, two days before V-E Day. The 1,200 project members reached their destination on May 29. The advance air echelon of transport planes and other support aircraft arrived on May 18.

By the first week of July, 18 bombers had arrived at Tinian for modification. The self-contained 509th lived in relative isolation near North Field, one of two air bases on the island. It included the 393rd Bomber Squadron, the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron, the 390th Air Service Group, the 603rd Air Engineering Squadron, the 1027th Air Materiel Squadron and the First Ordnance Squadron.

The target

Col. Paul W. Tibbets (center) recruited Capt. Theodore J. Van Kirk (left) as navigator and Maj. Thomas W. Ferebee as bombardier from his former B-17 crew.

By the end of May, Groves’ target committee had recommended the bombing of Kyoto; Hiroshima, an important center of military operations; Yokohama; or Niigata, which had replaced the earlier choice of Kokura. Later, Nagasaki would replace Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan as well as a historical city of great religious significance.

On May 31, 1945, members of the interim committee on postwar atomic policy held a meeting to discuss the possibility of warning Japan about the impending attack, to allow time to evacuate. Members rejected the idea, reasoning that if warned, the Japanese might try to shoot down the bomber or move prisoners of war into the target area.

In mid-June, Truman gave preliminary approval for ground invasion plans against Japan. On July 16, Allied leaders assembled for the Potsdam Conference, to discuss the peace settlement in Europe and to issue a surrender ultimatum to Japan. On that same day, the first atomic bomb was tested in the New Mexico desert near Alamogordo.

Shortly after Japanese Prime Minister Suzuki announced that his government would ignore the Potsdam Declaration, Tibbets received his orders for “Special Bombing Mission 13″—the 12 previous missions had been flights to Japan with non-atomic “pumpkins.”

In early August, bad weather over Japan cleared. On Aug. 5, a Teletype machine transferred a grave message.

“They were saying, ‘Go ahead and use the bombs. Truman has approved it,'” Tibbets recalled.

Gen. Curtis LeMay announced that Aug. 6 would be the date of Operation Centerboard, the dropping of the first atomic bomb. The primary target would be Hiroshima.

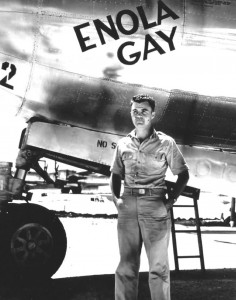

At Tibbets’ request, his B-29 Superfortress now bore the name Enola Gay, on the left side of the nose, beneath the cockpit. The Enola Gay would be rendezvousing with three other aircraft over Iwo Jima, for their formation flight to the target. The Great Artiste, piloted by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, would carry scientists as well as instrument packages that would be dropped to measure the intensity of the blast. George Marquardt’s photo plane, Necessary Evil, also carried scientists. Top Secret, piloted by Chuck McKnight, would travel as far as Iwo Jima, where it would wait in case Tibbets’ plane encountered trouble in route.

Since visual sighting was required to drop the bomb, a weather plane would fly to the primary target, with others flying to alternate target cities. From there, they would radio Tibbets with weather conditions. The aircraft participating in this mission were Straight Flush, piloted by Maj. Claude Eatherly, destined for Hiroshima; Jabbitt III, commanded by Maj. John Wilson, to Kokura; and Full House, Maj. Ralph Taylor’s plane, to Nagasaki.

Gen. Carl Spaatz decorated Col. Paul W. Tibbets Jr. with the Distinguished Service Cross immediately upon his return to Tinian Island on Aug. 6, 1945.

Tibbets and bombardier Tom Ferebee studied maps and aerial photographs of Hiroshima and the surrounding area. They would start their bomb run at a geographical feature east of the city. The aiming point would be the Aioi Bridge, near the heart of the city.

On Aug. 5, many stopped by to scrawl messages on the side of the bomb. That evening, Tibbets shared a platform with Professor Ramsey and Navy Capt. William S. “Deak” Parsons, an ordnance officer who would be the weaponeer on the flight. Those gathered listened in awe as they were told about the mission of the Enola Gay: to drop a bomb with a destructive force equivalent to 20,000 thousand tons of TNT.

Shortly after 1:00 a.m., Aug. 6, Tibbets arrived at the flight line. Those who climbed aboard the Enola Gay early that morning included Lewis, Ferebee, Van Kirk and Parson. Lt. Jacob Beser would be serving as radar countermeasures officer, Sgt. Joe Stiborik as radar operator, Staff Sgt. George R. Caron as tail gunner, Sgt. Robert H. Shumard as assistant flight engineer, Pfc. Richard H. Nelson as radio operator, Tech. Sgt. Wyatt E. as flight engineer and 2nd Lt. Maurice Jeppson as assistant weaponeer.

According to Van Kirk’s historic but unofficial log, the Enola Gay, powered by four 2,200-hp Wright Cyclones and carrying a heavy load of 7,000 gallons of gasoline and a four-and-one-half-ton bomb, lifted off the runway at 0245.

On target

At 0555, the Enola Gay arrived over Iwo Jima, and began circling, waiting for the other aircraft. As planned, Top Secret landed, and the other three planes circled to get into formation. At 0607, they were on their way.

“I never talked to them again until we were on the bomb run, like I’d arranged,” Tibbets said.

Nearing Hiroshima, Tibbets climbed slowly toward what was to be their bombing altitude, 30,700 feet. The awaited weather message came from Straight Flush, high over Hiroshima. The cloud cover was less than three-tenths at all altitudes—not enough to hinder a visual bomb drop.

They were eight minutes away from the scheduled bomb release when Hiroshima came into view. As they approached the city, Ferebee spotted the bridge from a distance of 10 miles. Ninety seconds from bomb release, Tibbets turned the plane—on autopilot—over to Ferebee. From six miles up, he could make out the city below in the early morning sunlight.

As they approached the aiming point, Tibbets saw no signs of antiaircraft fire or approaching fighter planes. Sixty seconds before the scheduled bomb release, he flicked a toggle switch, activating a high-pitched radio tone, which sounded in the headphones of the men aboard their plane, the two nearby and the weather planes, already more than 200 miles away. Exactly one minute after the tone began, the pneumatic bomb bay doors automatically opened. Tibbets announced, “On the run,” and began his countdown.

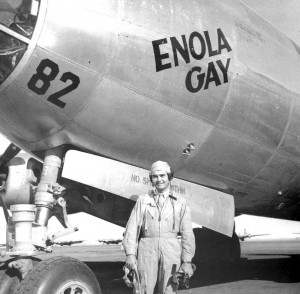

The Enola Gay was turned over to the Smithsonian Institution in 1949. Left to right are Carl Mitman (representing the Smithsonian), Col. Paul Tibbets, Maj. Thomas Ferebee and Maj. Gen. Emmett “Rosie” O’Donnell.

The time on Tibbets’ watch was 0915, plus 17 seconds, when they released “Little Boy.” They had arrived over the target and released their bomb and instrument packages just 17 seconds behind schedule.

Tibbets made a 155-degree diving turn to the right as Sweeney made a similar sharp turn to the left. With movie and still cameras poised, Marquardt lagged behind. “Little Boy” exploded at the preset altitude of 1,890 feet, 43 seconds after release. Suddenly, Caron, the only one aboard that plane to see the incredible fireball, saw the shock wave approaching.

“Just as I brought the Enola Gay up to horizon, the whole place lit up,” Tibbets said. “The next thing you knew, ‘wham!’ The shock wave hit the tail and then the second one came through.”

Accelerometers on the plane would later determine that the Enola Gay was 10 and a half miles away when the bomb exploded. As soon as they were safe from the blast’s effects, Tibbets began circling. They weren’t prepared for the “giant purple mushroom” that had already risen to a height of 45,000 feet. At the base of the cloud, fires sprang up; the city they had seen earlier was now an “ugly smudge.”

In his biography, Tibbets recalls awe and astonishment, as well as feelings of shock and horror sweeping over crewmembers. He also remembers a feeling of relief as they winged their way back toward Tinian, their task accomplished.

The Enola Gay touched down on the runway at Tinian at 1458, to a surprise welcome committee of more than 200 officers and enlisted men. Shortly after they arrived, Gen. Carl Spaatz pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbets’ flight coveralls.

Although it was estimated that 60 percent of Hiroshima was desolate, the Japanese refused to acknowledge the devastation. Plans moved ahead for the dropping of “Fat Man.”

Tibbets had selected Sweeney to pilot Bock’s Car for the mission. Although Kokura was the primary target, poor visibility led his crew to drop “Fat Man” on the secondary target, Nagasaki, on Aug. 9.

On Aug. 15, Japan announced its acceptance of terms of surrender. A peace treaty was signed aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Harbor on Sept. 2.

The two bombs’ casualty estimates widely vary, but one of the most commonly quoted is that approximately 140,000 died in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki, immediately or within months of the bombings, with tens of thousands more suffering or dying in later years from exposure to radiation.

Looking ahead to the psychological effect on the lives of those who participated in the mission, Truman once summoned Tibbets to the White House and said, “Don’t ever lose sleep over the fact that you planned and carried out that mission. It was my decision. You had no choice.”

During those initial days and then months and years after the atomic bombing, Tibbets said few serious questions were raised about the use of the weapon, although he did hear “scattered rumblings of the criticism that lay ahead.”

“We were at war; our job was to win it,” he said.

A revolutionary idea

With the end of the war in 1945, Tibbets’ organization was transferred to what is now Walker Air Force Base, Roswell, N.M., and remained there until August 1946. A few years later, his wartime experiences were the subject of “Above and Beyond,” a film released in 1952. Robert Taylor played Tibbets and Eleanor Parker played his wife, Lucy. The film showed some of the strains of working on the atomic bomb project, including the stress on married life. Three years after the movie was released, the Tibbets’ 17-year marriage ended. He would later marry Andrea Quattrehomme.

Responsible for the Air Force’s purchase of a six-engine jet bomber, Tibbets was in charge of a detachment conducting service tests in the B-47 Project WIBAC (Wichita Boeing Airplane Company). The project continued into 1954, and was absorbed into the Air Training Command, as McConnell AFB was built there.

Tibbets later commanded two Strategic Air Command bomber organizations, conducted a tour with NATO in France and was responsible for establishing the National Military Command Center at the Pentagon. He retired after 29 years and seven months of service in the Air Force, on Aug. 31, 1966.

That year, he received an SOS call from Brig. Gen. Olbert “Dick” Fearing Lassiter, an ace with seven confirmed kills who had been assigned to Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, Omaha, before coming to work with Tibbets on the B-47 project.

Nicknamed “Rapid Richard” because of his lust for excitement and fast living, Lassiter retired from the Air Force in 1964, shortly after incorporating a civilian jet service in Delaware. His revolutionary idea was to sell jet transportation on a contract basis.

“Companies would buy his services, and he would have a jet where they wanted it, when they needed it, and take their people wherever they wanted to go,” said Tibbets.

Initially, Lassiter adopted the SAC idea of having airplanes alert around the clock, ready to respond to an emergency anywhere in the world. He sold the idea to many friends he’d made during his military career. His board of directors included Jimmy Stewart, Arthur Godfrey, LeMay, James Hopkins Smith (former assistant secretary of the Navy) and Monroe J. Rathbone (former chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey).

Lassiter made plans to open offices and base jets in five cities around the country. Lassiter had done some work with Bill Lear when he was developing the Learjet and naturally chose a Lear as his first airplane. After relocating Executive Jet Airways to Columbus, he changed the company name to Executive Jet Aviation, in 1965. A subsidiary, Executive Jet Aviation, SA, opened in Geneva, Switzerland, with plans to fly American businessmen while they were in Europe.

Learjets didn’t have nonstop ocean-flying capability, but Lassiter hoped EJA would pick up businessmen near their homes and take them to airports to board international flights. When they arrived at their European destination, an executive jet would be waiting to speed them to their final destinations abroad.

Lassiter’s request for Tibbett’s help was regarding his Swiss operation. Tibbets, appointed executive vice president and general manager of EJA, SA, went to Switzerland to get the company, which had been disregarding Swiss regulations, back into the good graces of officials. He succeeded in doing that, but a maze of clearance and custom regulations continued to hinder the business, and Europeans didn’t jump at the chance to do business with an American firm. Eventually, EJA, SA was sold, with EJA maintaining a small interest in the company. Tibbets returned to the U.S. after two years in Geneva.

He recalled that he and others resigned from the board in the late 1960s, because of some of Lassiter’s business practices. The company came under scrutiny when it tried to obtain a supplemental air carrier certificate to operate Boeing 707 and 727 airliners it had acquired. The Civil Aeronautics Board blocked that move when it discovered that the American Contract Company of Wilmington, Del., a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, had supplied the company’s financing when it was formed. The railroad was ordered to divest itself of its interest.

Barred from using the larger jets for domestic operations, Lassiter leased them to International Air Bahama, a Lichtenstein corporation organized by foreign investors offering cut-rate service between Nassau and Luxembourg.

With EJA headed for financial ruin, the Detroit Bank and Trust Co., representing the majority of shares in the company, authorized Lassiter’s removal as president. In June 1970, Harry Pratt of Detroit Bank and Trust and Bruce Sundlun, a Washington attorney and member of the Executive Jet board of directors, seized all company records.

After being named president of EJA, Sundlun worked to save the business. Sundlun and two partners borrowed $1.25 million and bought EJA in 1972.

Part of his effort to make the company profitable was to enlist Tibbets, now living in Florida, to come to Columbus. In April 1976, Tibbets became president of the company.

“Sundlun managed to get the big jets off the books and brought the company sufficiently into the black,” Tibbets said.

By the late 1970s, EJA was doing business with approximately 250 contract flying customers. It routinely flew throughout the U.S., parts of Canada, the Caribbean, Central and parts of South America, logging more than three million miles a year.

In the mid-1980s, Richard Santulli, the founder of RTS Capital Services and a former Goldman Sachs principal, purchased the company. Tibbets, with 400 hours of Learjet flight under his belt, decided it was time to “leave the flying to younger men” and retired, but remained on in a consulting arrangement for a year.

Two years later, at the National Business Aviation Association’s annual conference, EJA introduced the “fractional ownership concept,” through NetJets. In 1998, Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. acquired Executive Jet, for $725 million. The company’s name was later changed to NetJets Inc.

A place in history

The Enola Gay arrived at Davis-Monthan Army Air Field, Arizona, in July 1946. In August, she was placed in storage and dropped from the Army Air Forces inventory.

Almost three years later, in July 1949, Tibbets flew her to Park Ridge, Ill. (now O’Hare Airport), for acceptance by the Smithsonian Institution for restoration and display. She was moved twice for temporary storage. During the next seven years, the aircraft suffered the effects of weather as well as damage from vandalism and souvenir hunters.

In August 1960, disassembly began for transfer to the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage Facility at Suitland, Md. Finally, restoration began in early December 1984.

For the 50th anniversary of the end of WWII, the Smithsonian planned a special exhibit, with the Enola Gay as its centerpiece. Tibbets said a script, written under the direction of Dr. Martin Harwit, completely ignored the aircraft’s role in ending the war, instead making it “appear the callused instrument of a vengeful nation’s genocide from above.” The exhibit, Tibbets said, had been “weighted heavily with the emotionally charged freight of 50 years of anti-nuclear sentiment.”

In June 1995, the forward section of the fuselage, as well as the flight deck and bomb bay, were put on display at the Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Four million people visited the exhibit before it closed in May 1998.

The pieces were then returned to the Garber facility. When the museum opened its new Udvar-Hazy Center, the Enola Gay was placed on display there.

Paul W. Tibbets Jr. was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1996. His awards and decorations include the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, European Campaign Medal, Joint Staff Commendation Medal, American Defense Service Medal, WWII Victory Medal, Air Force Outstanding Unit Award and American Campaign Medal.

Over the years, Tibbets often looked back on those two momentous events in his life: dropping Baby Ruth candy bars on unsuspecting race fans at Hialeah and nearby beachgoers in 1927, and his role in the dropping of “Little Boy” on Hiroshima 18 years later. He said the mission to Hialeah was definitely “more exciting.”

“The day I dropped the bomb was the most boring flight I ever made,” he said, and then explained. “Nothing went wrong. It was just like a clock. When LeMay was asked what he thought about it, he said it was a textbook performance.”

Many will agree with why Tibbets thought the earlier flight was so exciting.

“There’s nothing to match the thrill of a 12-year-old boy’s first airplane ride,” he said.