By Di Freeze

Finale

“The day I dropped the bomb was the most boring flight I ever made,” Brig. Gen. Paul W. Tibbets, USAF, ret., recently said. “Nothing went wrong. It was just like a clock. LeMay himself was asked what he thought about it. He said it was a textbook performance.”

During the first week of August 1945, Tibbets watched, and waited.

“Of course, we knew about when President Harry Truman was supposed to be meeting with Stalin and Churchill,” he recalled. “We knew because of the Teletype machine that was brought into our area, at the request of General Lester Groves, so they could talk back and forth to Brigadier General Tom Farrell, the Corps of Engineer man. We knew what was going on, almost by segments. We were watching that. I felt confident we were going to get word to go as fast as Truman could get to us—if we didn’t get word to go and unload. I had everything ready.”

On August 5, that word finally came. Gen. Curtis LeMay was telling them August 6 would be the date of “Operation Centerboard,” the dropping of the first atomic bomb. As for the primary target of the operation, it would be Hiroshima, an important center of military operations. There were also two alternate targets.

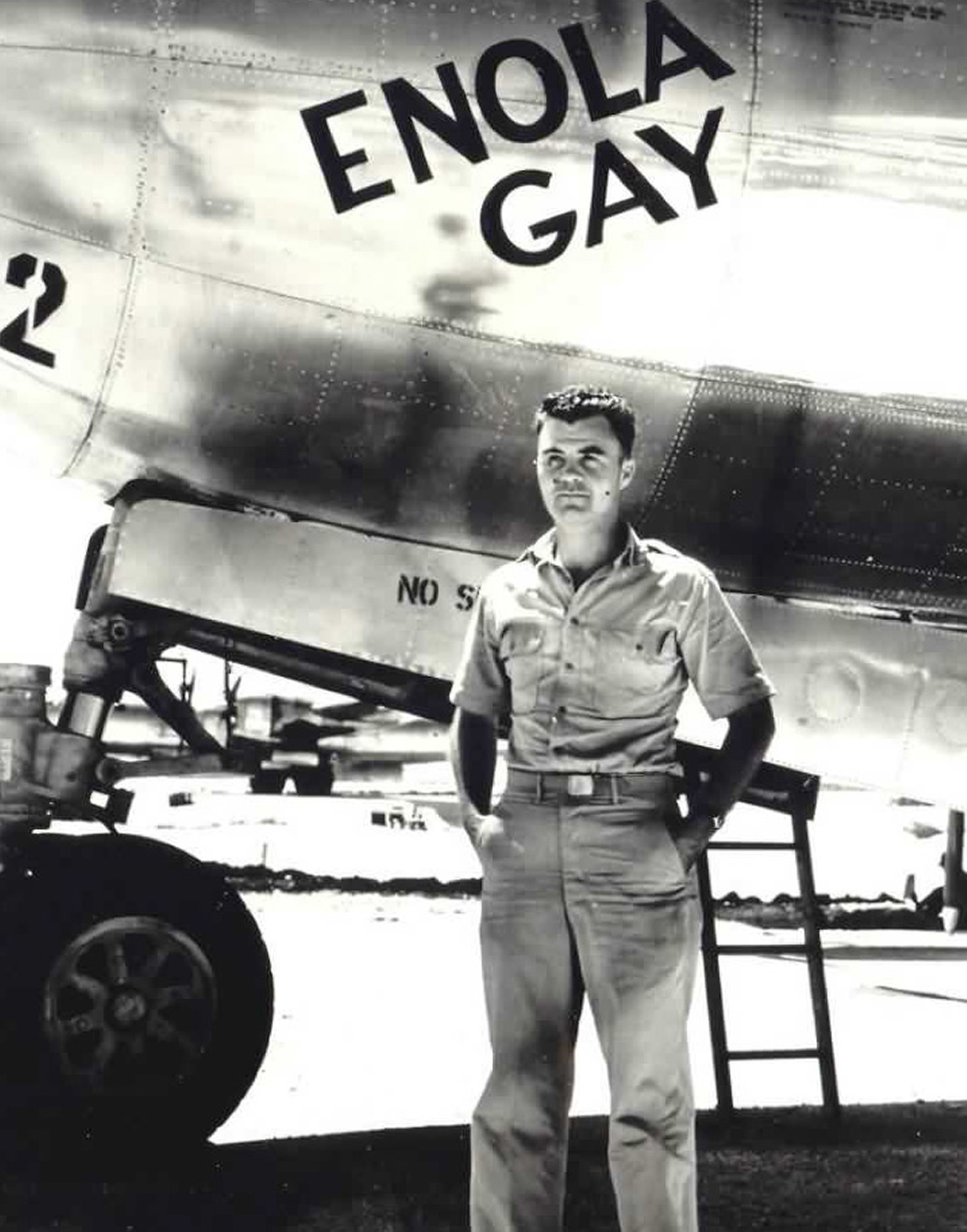

Once that was settled, Tibbets handled the last-minute tasks, which including seeing that the recently chosen name for his B-29 Superfortress, number 82, adorned her. Recently, he had chosen “Enola Gay,” the name of his mother, who had been a source of strength to him since boyhood, particularly during the soul-searching period when he decided to give up a medical career to become a military pilot.

Besides asking the painter to place the name on the left side of the nose, beneath the cockpit, Tibbets had asked that the 509th Composite Group’s insignia, its familiar arrowhead tail motif, be replaced with the standard identifier for the Sixth Bomb Group—a big black letter “R” inside a circle. That change was also made on six other Superfortresses taking part in the mission.

Another detail to be worked out was the rendezvous between the Enola Gay and three other aircraft, over Iwo Jima, and their further flight in formation to the target. The Great Artiste, piloted by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, would be carrying instrument packages—which would be dropped to measure the intensity of the blast, and to record shock effect, radioactivity, etc.—as well as a number of scientists. George Marquardt’s photo plane, “91,” also carrying scientists, would lag far enough behind to be out of the radius of immediate danger. Top Secret, piloted by Chuck McKnight, would travel as far as Iwo Jima, where it would wait as a spare, in case Tibbets’ plane encountered trouble in route. After outlining the procedure, Tibbets had just one thing left to say. When he left that rendezvous point and headed toward the target, he expected those planes to be with him!

Since visual sighting was required to drop the bomb, a weather plane would fly to the primary target, with others flying to alternate target cities, where they would radio Tibbets as to if weather conditions were suitable for a visual bomb drop. Those were Straight Flush, piloted by Maj. Claude Eatherly, destined for Hiroshima; Jabbitt III, commanded by Maj. John Wilson, to Kokura; and Full House, Maj. Ralph Taylor’s plane, to Nagasaki.

At one point Tibbets and Tom Ferebee, the bombardier, studied maps and aerial photographs of Hiroshima and the surrounding area. A geographical feature east of the city was chosen as the initial point, where they would start their bomb run. The aiming point would be the Aioi Bridge, near the heart of the city, whose T-shape, due to a ramp in the center, made it easily recognizable.

Now, all that was left was the final briefing.

“We needed to discuss the latest in weather, the latest in location of enemy opposition and that sort of thing, like the “Dumbo” boats that were out on the water, in case you got shot up and had to abandon the airplane in the water,” Tibbets said. “We got all that done. It was as smooth as can be.”

Attendees at that briefing included Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Farrell, the Manhattan District’s ranking officer on the scene; Admiral William R. Purnell; Navy Captain William S. “Deak” Parsons, an ordnance officer who would be the weaponeer on the flight; Commander Frederick L. Ashworth, another weaponeer; Professors Ramsey and Robert Brode.

Later, as the time quickly passed, many stopped by to scrawl messages on the side of the bomb, and Tibbets was introduced to William L. Laurence, a New York Times science writer who had been given leave of absence to work for the government and write the official history of the atomic development.

That evening, Tibbets shared a platform with Parsons and Ramsey. He told those gathered that their long months of training would finally be put to the test, and shed some light on just what they had been training for, saying that the Enola Gay would drop a bomb different from any they had ever seen, which contained a destructive force equivalent to 20,000 thousand tons of TNT.

Shortly after one o’clock, the men returned to their quarters to pick up flying gear, and in the case of Tibbets, his ever-present smoking gear—cigars, cigarettes, pipe tobacco and pipes. Later, when he arrived at the flight line, the Enola Gay, which now held “Little Boy” in her front bomb bay, was bathed in floodlights. Motion picture cameras were set up and still photographers stood by with their equipment. Finally, Capt. Theodore J. “Dutch” Van Kirk, Tibbets’ navigator, pointed out they needed to be “wheels up at 0230,” in order to make the planned rendezvous and be over the target in time to drop the bomb at the appointed time. That would put them in the air about an hour behind the weather planes, which had taken off at 0137.

Those who climbed aboard the “Enola Gay” that early morning included Col. Tibbets, born in the Midwest but raised in Florida; Capt. Robert A. Lewis, Ridgefield Park, N.J., copilot; Ferebee, from Mocksville, N.C.; and Van Kirk, from Northumberland, Penn.

Lt. Jacob Beser, Baltimore, Md., would be serving as radar countermeasures officer; Sgt. Joe Stiborik, Taylor, Texas, radar operator; Staff Sgt. George R. Caron, Lynbrook, N.Y., tail gunner; Sgt. Robert H. Shumard, Detroit, Mich., assistant flight engineer; Pfc. Richard H. Nelson, Los Angeles, radio operator; and Tech. Sgt. Wyatt E. Duzenbury, Lansing, Mich., flight engineer. The remaining two crewmembers were Parson, from Santa Fe, N.M., and Second Lt. Maurice Jeppson, Carson City, Nev., the assistant weaponeer.

According to Van Kirk’s historic but unofficial log, the “Enola Gay,” powered by four 2,200-hp Wright Cyclones, and carrying a heavy load of 7,000 gallons of gasoline and a four-and-one-half-ton bomb, lifted off the runway at 0245.

For the safety of Tinian Island, Parsons had proposed he make the final assembly of “Little Boy” during the early stages of the flight; that proposal was accepted, since a double-plug system that had been developed for the bomb made the plan feasible. And so, on that pleasant tropical night, eight minutes after they left the ground, Parsons and Jeppson lowered themselves into the bomb bay. There, they inserted a slug of uranium and the conventional explosive charge—which would send one block of uranium into the other to set off an instant chain reaction that would create an atomic explosion—into the core of “Little Boy.”

Rendezvous

At 0555, the Enola Gay arrived over Iwo Jima, and, as had been earlier planned, began circling, waiting for the other aircraft.

“Then, Caron said, ‘Here’s The Great Artiste. Here’s Bock’s Car!” recalled Tibbets.

As planned, Top Secret landed, and the other three planes circled to get into formation. At 0607, they were on their way.

“I never talked to them again until we were on the bomb run, like I’d arranged,” Tibbets said.

Nearing Hiroshima, a thin layer of clouds beneath them caused some misgivings. Still, Tibbets climbed slowly toward what was to be their bombing altitude, 30,700 feet. They were almost at that level when the awaited weather message came in code from Straight Flush, high over Hiroshima. The cloud cover was less than three-tenths at all altitudes—not enough to hinder a visual bomb drop.

It was 0830 when they arrived over the shoreline, and flew across Shikoku toward the Iyo Sea. They were eight minutes away from the scheduled time of bomb release when Hiroshima came into view.

“Do you all agree that’s Hiroshima?” Tibbets asked the other crewmen, who promptly concurred.

Just south and west of the initial point, 15 1/2 miles east of the point in the heart of the city that was to be their target, Tibbets made a leftward turn of 60 degrees, and came over the point at a heading of 264 degrees, flying almost due west. The reason for this approach, and the reason they had chosen an IP to the east of their target, was that the prevailing winds in the area were known to be from the west. It was desirable, from the standpoint of accuracy, to make a bomb run against the wind.

On that morning, however, the wind was from the south, at 10 mph. Tibbets didn’t worry about the unpredictable variance; Ferebee was “an old hand at dropping bombs with the wind, against it or in a crosswind.”

As they zeroed in on the target, Tibbets reminded all crewmembers to put on their goggles, and keep them poised on their foreheads until the bomb was released; at that time, the Polaroids were to be slipped over their eyes to protect them from the blinding glare of the bomb blast, calculated to have the intensity of 10 suns. “The Great Artiste” and No. 91, which had dropped back a little during the approach, were given the same order.

All that was necessary, upon reaching the I.P., was to fly the predetermined heading, with calculated allowance for the direction and velocity of the wind. When the navigator and bombardier compared notes, they agreed their ground speed was 285 knots (330 mph); a drift to the right required an 8-degree correction. Adjustments were made to the bombsight, now engaged to the autopilot for the bomb run. As they approached the city, Ferebee, Van Kirk and Tibbets strained to find the aiming point. Ferebee spotted the bridge from a distance of 10 miles. “No question about it,” Van Kirk said, scanning an air photo for comparison.

On Target

Ninety seconds from bomb release, Tibbets turned the plane, on autopilot, over to Ferebee. From six miles up, he could make out the city below, shimmering in the early morning sunlight.

As they approached the aiming point, Tibbets saw no signs of antiaircraft fire or of approaching fighter planes sent up to intercept them. He would later learn that Eatherly’s weather plane had set off air raid sirens; however, when nothing happened then, theirs were ignored. Now, Ferebee looked intently into the viewfinder of the bombsight, and announced that they were on target.

Sixty seconds before the scheduled bomb release, he flicked a toggle switch, activating a high-pitched radio tone, which sounded in the headphones of the men aboard their plane, the two nearby, and the weather planes, already more than 200 miles away. Exactly one minute after it began, the tone ceased, and in its place could be heard the sound of the pneumatic bomb bay doors automatically opening. Next, over the radio, Tibbets announced, “On the run,” and began his planned count down.

“I got the one out of my mouth, and the damned airplane was jumping, because I lost 9,000 pounds in the front,” Tibbets recalled.

By Tibbets’ watch, “Little Boy” was released at 0915, plus 17 seconds. In Hiroshima, it was 0815, since they had crossed a time zone. They had arrived over the target and released their bomb, after a 2,000-mile flight, just 17 seconds behind the prearranged target time. As had been arranged, the instrument packages had been released at the same time, suspended from parachutes.

Tibbets needed to quickly put as much distance as possible between the plane and the point at which the bomb would explode, beginning with a 155-degree diving turn to the right, as Sweeney made a similar sharp turn, but to the left. Marquardt, however, with movie and still cameras poised, lagged behind.

Lewis and Tibbets had slipped their dark glasses on, but soon pushed them back on their foreheads, after discovering they made it impossible to fly the plane through the difficult getaway maneuver, because the instrument panel was blacked out, and realizing they’d be flying away from the actual flash when it occurred.

Ferebee, in the bombardier’s position, was so fascinated by the bomb’s free-fall that he forgot all about the glasses. Caron, in the tail, was the only one aboard that plane to see the incredible fireball, “a boiling furnace with an inner temperature calculated to be one hundred million degrees Fahrenheit.”

“Little Boy” exploded at the preset altitude of 1,890 feet above the ground, 43 seconds after its release. Suddenly, Caron saw the shock wave approaching, at the speed of sound, or almost 1,100 feet a second. At the same time, Tibbets was bringing the “Enola Gay” up to horizon, after dropping it to gain speed, and turn.

“Just as I brought it up to horizon, the whole place lit up,” he said. “The next thing you knew, wham! The shock wave hit the tail. The second one came through; it was pretty good. “I had accelerometers in the airplane. When all the calculations were done the next day, they figured out that when that bomb exploded, the “Enola Gay” was 10 and a half miles from that particular point of explosion, because my accelerometers showed 2 and 1/2 G forces.”

L to R: Sgt. Ed Buckley, radar operator on The Great Artiste, and Enola Gay crewmembers Sgt. Joseph Stiborik, radar operator, with S-Sgt. George R. Caron, tail gunner.

Tibbets would later say his “teeth” alerted him to the explosion, more than his eyes had; he found out the tingling sensation in his mouth and the taste of lead on his tongue were the results of electrolysis, an interaction between the fillings in his teeth and the radioactive forces loosed by the bomb.

As soon as he knew they were safe from the effects of the blast, Tibbets began circling to view the results. Although Caron had described a mushroom-shaped cloud that seemed to be coming toward them, they weren’t prepared for the sight that met their eyes. The “giant purple mushroom” had already risen to a height of 45,000 feet. At the base of the cloud, fires sprang up “amid a turbulent mass of smoke that had the appearance of bubbling hot tar.” The city they had seen earlier was now an “ugly smudge.”

In his two biographies, Tibbets recalls that besides awe and astonishment, a feeling of shock and horror swept over crewmembers. Although a movie reenactment of the historic flight had Tibbets saying, “My God, what have we done,” he says he really doesn’t remember what he or others said.

He does remember, however, the feeling of relief as they winged their way back toward Tinian, their task accomplished.

The “Enola Gay” touched down on the long runway at Tinian at 1458, to a surprise welcome committee. Up to that point, said Tibbets, there had been “reasonably tight security.” Upon their return, more than 200 officers and enlisted men gathered.

“Everybody and their brother was there,” he said. “General Spaatz was there and the people from Guam; Admiral Kincaid was there for Admiral Nimitz.”

Shortly after they arrived, Spaatz would pin the Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbets’ rumpled flight coveralls.

“Fat Boy”

That evening, a bulletin on Tokyo radio said that a “few” B-29s had hit Hiroshima that morning with incendiaries and bombs. The damage, they said, was under survey. Even the next morning, reference was being made to incendiaries that caused “some damage,” but by mid-afternoon there was a reference of “a new-type bomb.”

Photo planes that had flown over Hiroshima four hours after the bomb blast reported it was impossible to obtain clear pictures of the damage; the city still lay under a dense blanket of smoke, and fires burned everywhere.

On August 7, Truman, on his way home from the Potsdam Conference, announced over the radio that an atomic bomb had been dropped. A dispatch from Washington said the bomb had been developed at a cost of two billion dollars, and would pay for itself if it shortened the war by only nine days, based on a calculation that the war was costing seven billion dollars a month.

By that day, aerial photos made it possible to announce that 60 percent of Hiroshima, or approximately 4.1 square miles, had been laid waste (only a few of the sturdier buildings in the area remained standing); it was estimated that the loss of life was in the neighborhood of 80,000.

At that time, when asked if he thought the mission would end the war, Tibbets responded, “Yes, unless the Japanese have taken leave of their senses.” He would later note that at a press conference at the time, no one questioned the use of the bomb, although controversy developed later.

“The reporters had seen the war first hand, and like every soldier I met, welcomed anything that would shorten the conflict,” he explained.

To indicate that America had an endless supply of this “superweapon,” a second drop was scheduled for Aug. 9. This bomb would be the pumpkin-shaped “Fat Man,” which utilized plutonium. When Japan didn’t capitulate, plans moved ahead.

Tibbets had selected Sweeney, normally the commander of The Great Artiste, for Special Bombing Mission #16. Since that aircraft had been outfitted with special instruments for the Hiroshima flight, Sweeney would be piloting Bock’s Car, normally commanded by Capt. Frederick C. Bock.

Major Sweeney’s crew was 1st Lt. Charles Albury, copilot; Capt. James Van Pelt Jr., navigator/radar operator; Capt. Kermit Beahan, bombardier; Lt. Jacob Beser, electronic countermeasures; Staff Sergeant Ed Buckley, radar operator; Sgt. Abe Spitzer, radar operator; Master Sergeant John Kuharek, flight engineer; Sgt. Raymond Gallagher, gunner/assistant flight engineer; and Staff Sergeant Albert Dehart, tail gunner. 2nd Lt. Fred Olivi served as third pilot. U.S. Army Air Force Lt. Phillip Barnes assisted U.S. Navy Commander Frederick Ashworth, serving as weaponeer, in monitoring the bomb.

In “The Tibbets Story” (1978), Tibbets tells briefly of the problems that plagued that mission, including a fuel pump malfunction that made it impossible to use 600 gallons of fuel in the bomb bay tanks, and a delay at the rendezvous point south of Kyushu, when one of the accompanying planes failed to show up and 45 minutes were lost.

Later, Beahan found it impossible to positively identify his aiming point and primary target, Kokura, due to poor visibility, and a smoky haze that obscured the skyline, the result of recent incendiary bombing of a neighboring city. Sweeney circled for almost an hour, before giving up. Finally, a last minute break in the clouds allowed the bombardier to visually bomb the secondary target. The bomb detonated at 1100, Nagasaki time. With fuel critically low, Sweeney turned toward Okinawa, where he landed, with nearly empty tanks, to refuel before returning to Tinian.

The difficulties, said Tibbets, extended to the press reports of the raid, in which Bill Laurence listed The Great Artiste as the aircraft that dropped the bomb, instead of Bock’s Car.

However, the Nagasaki raid was successful, Tibbets said, in the sense that it helped convinced the Japanese government that further resistance meant atomic disaster. On August 10, Japan offered to surrender, with conditions. However, that offer was refused, and hostilities continued. Then, on August 14, 828 B-29s dropped incendiaries, high explosives and mines on five Japanese cities. The following day, Japan announced its acceptance of the terms of surrender of the U.S. A peace treaty was signed aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Harbor on September 2.

Scientists were anxious to get into Japan to check on the results of the bomb drops. Tibbets also wanted to visit the country, and accompanied occupying forces in the second wave of aircraft that arrived in the Japanese capital; he later visited the bombed cities, as did Ferebee and Van Kirk.

He said the brief visit left him with “respect for the people who had been our enemies such a short time before,” adding he felt no animosity, or feelings of guilt about his role in ending the war.

There is a wide array of estimates on casualties of the bombing, but one of the most widely quoted is that approximately 140,000 died in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki immediately or within months of the bombings, with tens of thousands more suffering or dying in later years from the exposure to radiation.

Looking ahead to the psychological effect on the lives of those who participated in the mission, President Truman once summoned Tibbets to the White House and said, “Don’t ever lose sleep over the fact that you planned and carried out that mission. It was my decision. You had no choice.”

During those initial days, months and years after the atomic bombing, however, Tibbets said few serious questions were raised about the use of the weapon, although they did hear “scattered rumblings of the criticism that lay ahead.”

Over the decades, he has traveled the country telling his story. He’s also received hundreds of letters from people all over the world. Some of the writers have condemned him as “a war criminal,” but the vast majority has expressed thanks for what he feels was simply his job.

“We were at war; our job was to win it,” he says.

Although he didn’t feel guilt over his role, he has said he feels a “sense of shame for the whole human race, which through all history has accepted the shedding of human blood as a means of settling disputes between nations.”

Above and Beyond, Rapid Richard and Executive Jet

With the end of the war in 1945, Tibbets’ organization was transferred to what is now Walker Air Force Base, Roswell, N.M., and remained there until August 1946.

During that period, Tibbets was retained as a technical advisor on the Bikini Bomb Project. However, he said his “technical advice” was seldom solicited and “not heeded when volunteered.”

A few years later, Tibbets’ wartime experiences were the subject of “Above and Beyond,” a film released in 1952. Robert Taylor, who had earned a flying license before the war and went into naval aviation as an instructor, played Paul Tibbets; Eleanor Parker played his wife, Lucy.

The film showed some of the strains of working on the atomic bomb project, including the stress on married life, much of it to do with the secrecy that had to be maintained. Lucy’s questions regarding the project were met with required lies or with the answer that a question was “none of her business.”

In fact, three years after the movie was released, the Tibbets’ 17-year marriage ended. In May 1956, he married Andrea Quattrehomme, a divorcee he met in Paris.

Hollywood delved further into stress in the military in “Strategic Air Command,” in which a former World War II pilot, portrayed by James Stewart, is called out of retirement to assist in the strengthening of the new bomber forces, America’s first line of defense against the Russian nuclear threat. In the meantime, his wife (June Allyson) sits at home and frets over her husband’s devotion to duty.

Serving as technical director on this film was an old acquaintance of Tibbets’, Brig. Gen. Olbert “Dick” Fearing Lassiter. Stewart soon dubbed Lassiter, an ace with seven confirmed kills known for his lust for excitement and fast living, “Rapid Richard.”

Shortly after that movie was released, Lassiter, assigned to SAC headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, Omaha, and another officer brawled over obscenities voiced regarding Lassiter’s dog, which had been tied up at the entrance of a club. When LeMay found out Lassiter had knocked the brigadier general out cold, he turned to Tibbets for help.

Tibbets had been responsible for the Air Force’s purchase of a six-engine jet bomber and was in charge of a detachment conducting service tests in what was known as the B-47 Project WIBAC (Wichita Boeing Airplane Company). Knowing he couldn’t let both officers remain at Offutt without taking disciplinary action against them, LeMay asked Tibbets if he would take Lassiter into his outfit.

The project continued into 1954, and was absorbed into the Air Training Command, as McConnell AFB was built there. Tibbets soon left, but Lassiter stayed for a while, before going back to SAC and having a tour at Thule in northern Greenland and an assignment to Westover AFB in Massachusetts. In 1960, Lassiter was assigned to command the 801st Air Division at Lockbourne (now Rickenbacker) AFB at Columbus, Ohio.

After that tour, he was assigned to the Pentagon, but instead, retired from the Air Force, in 1964, shortly after incorporating a civilian jet service in Delaware, with the idea of selling jet transportation on a contract basis.

“Companies would buy his services, and he would have a jet where they wanted it, when they needed it, and take their people wherever they wanted to go,” said Tibbets.

He later decided to relocate Executive Jet Airways to Columbus, because of the friendships he had made there, the city’s central location, and because there was an available pool of jet pilots and mechanics and a hangar available at Port Columbus International Airport.

Initially, Lassiter adopted the SAC idea of having airplanes alert around the clock, ready to respond to an emergency anywhere in the world. He sold the idea to many friends he’d made during his military career. His board of directors included Jimmy Stewart, Arthur Godfrey, LeMay, James Hopkins Smith (former assistant secretary of the Navy) and Monroe J. Rathbone (former chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey).

Plans were made to open offices and base jets in five cities around the country. An alert facility with sleeping quarters was established at Port Columbus, but soon abandoned, when Executive Jet learned that most trips made by American businessmen are planned; the need for emergency jet transportation in the middle of the night was rare. When there was a need to get an airplane off in a hurry, it was sufficient to have a crew on alert at home.

Since he was a friend of Bill Lear and had worked with him on the development of the Lear jet, it was natural that his first airplane would be a Lear.

In 1965, the company name was changed to Executive Jet Aviation and a subsidiary, Executive Jet Aviation, SA, opened in Geneva, Switzerland, with plans to fly American businessmen while they were in Europe. The Lears didn’t have nonstop ocean-flying capability, but Lassiter hoped EJA would pick up businessmen near their homes and take them to airports to board international flights. When they arrived at their European destination, an executive jet would be waiting to speed them to their final destinations abroad.

The following year, Tibbets received an SOS call from Lassiter regarding the Swiss operation. Since Lassiter and Tibbets had parted company, Tibbets had commanded two of SAC’s bomber organizations, conducted a tour with NATO in France and had been responsible for establishing the National Military Command Center in the Pentagon. The last assignment Tibbets was given was to head the Department of Defense Transportation office at the Pentagon, where he was to be in charge of all ports of embarkation, both aerial and surface, in the military establishment. Instead, he decided to retire, after 29 years and seven months of service in the Air Force, on Aug. 31, 1966.

Then, after a brief period as a civilian, Tibbets became executive vice president and general manager of EJA, SA. Arriving in Switzerland, he found Swiss regulations being disregarded and government officials upset. Shortly thereafter, they were back within the good graces of those officials. But, a maze of clearance and custom regulations, as well as the fact that Europeans didn’t seem to want to do business with an American firm, hindered flying in Europe. Eventually, EJA, SA was sold, with EJA maintaining a small interest in the company. Tibbets returned to the U.S., after two years in Geneva.

When EJA was formed, it was a closely held secret that the American Contract Company of Wilmington, Del., a wholly owned subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, had supplied the financing. By the late sixties, the company was receiving no return on the investment; that concerned Tibbets less, he said, than the sidestepping of regulations that facilitated American Contract’s funding of EJA.

Not long after LeMay resigned from the board, in the summer of 1967, others followed his lead, including Tibbets, who told Lassiter he wanted out because he believed some things that were going on were flagrantly illegal. They parted “on a friendly basis” in 1968.

Lassiter continued buying Boeing 707 and 727 airliners. However, to operate the larger aircraft, he needed a supplemental air carrier certificate. The Civil Aeronautics Board blocked that move when the Penn Central connection was discovered. The railroad, which had invested $22 million in EJA, was ordered to divest itself of its interest.

Since he was barred from using the larger jets for domestic operations, Lassiter leased them to International Air Bahama, a Lichtenstein corporation he had persuaded a number of foreign investors to organize, which offered cut-rate service between Nassau and Luxembourg. However, although money was being made, lease money wasn’t getting back to Executive Jet. The money Lassiter raised, said Tibbets, allowed him to live like a millionaire. However, he added that Lassiter sometimes found it difficult to distinguish between his own resources and those of EJA.

“A weakness for beautiful women contributed to his problems, according to more than one magazine article that appeared while EJA’s difficulties were making headlines,” said Tibbets.

Lassiter maintained furnished apartments in New York and elsewhere, along with hotel suites in foreign cities including Rome (where he would ultimately die as the result of a brain tumor in 1973). In the meantime, EJA was going deeper into financial ruin.

Harry Pratt of the Detroit Bank and Trust Co., which held the Penn Central interest in an irrevocable liquidating trust, discussed the problem with Bruce Sundlun, a Washington attorney and member of the Executive Jet board of directors. The bank, representing the majority of shares in the company, authorized Lassiter’s removal as president.

“Pratt and Sundlun went to Columbus, and, in a surprise midnight raid on June 30, 1970, seized the Executive Jet headquarters at Port Columbus and began examining the company’s records,” said Tibbets.

Another agent of the bank took over the New York office. Sundlun was named president of EJA. It was expected that he would liquidate the assets, but instead, he decided to see if the business could be saved. An audit indicated the company had lost about $4 million each year, on revenues of $13.5 million.

When Tibbets, at the time living in Florida, heard about what had taken place, he called Sundlun, who asked if he had the interest and “gambling instinct” to come to Columbus to help him “make EJA swim.” He says the way EJA was turned around, under Sundlun’s guidance, was one of the nation’s great business success stories of the decade.

“He managed to get the big jets off the books and finally brought the company sufficiently into the black to make it a salable asset,” Tibbets said.

Nevertheless, Detroit Bank and Trust didn’t have success attracting buyers. Finally, Sundlun, Robert L. Scott Jr. and Joseph S. Sinclair borrowed $1.25 million to buy out Penn Central’s interest; the purchase was completed in 1972.

On April 21, 1976, Tibbets became president of Executive Jet Aviation, Inc.

By the late 1970s, EJA was doing business with approximately 250 contract flying customers. It routinely flew throughout the U.S., parts of Canada, the Caribbean, Central and parts of South America, logging more than three million miles a year.

In the mid-eighties, Richard Santulli, the founder of RTS Capital Services and a former Goldman Sachs principal, purchased the company. Tibbets, with 400 hours of Learjet flight under his belt, decided it was time to “leave the flying to younger men” and retired, but remained on in a consulting arrangement for a year.

Two years later, at the National Business Aviation Association’s annual conference, EJA introduced the “fractional ownership concept,” through NetJets. In 1998, Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. acquired Executive Jet, for $725 million. Last year, the company’s name was changed to NetJets Inc.

What Happened To The Enola Gay?

The Enola Gay arrived at Davis-Monthan Army Air Field, Arizona, in July 1946. In August, she was placed in storage, and dropped from the Army Air Forces inventory.

Almost three years later, in July 1949, Tibbets flew her to Park Ridge, Ill. (now O’Hare Airport), for acceptance by the Smithsonian Institution for restoration and display. In January 1952, she was flown to Pyote Air Force Base, Texas, for temporary storage, before again being flown, in December 1953, to Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, for temporary storage. During the next seven years, in a remote section of the base, the Enola Gay reportedly suffered from weather as well as damage from vandalism and souvenir hunters.

In August 1960, disassembly began for transfer to the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage Facility at Suitland, Md., which occurred in July 1961. The restoration of the Enola Gay began in early December 1984. In the mid-nineties, Tibbets found out that the Enola Gay was to be the centerpiece of an exhibit planned by the Smithsonian to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the end of WWII.

For Enola Gay’s coming out party, the Smithsonian, under the direction of Dr. Martin Harwit, wrote a script that, said Tibbets, completely ignored her role in ending the war and instead “made her appear the callused instrument of a vengeful nation’s genocide from above.” The exhibit, he said, had been “weighted heavily with the emotionally-charged freight of 50 years of anti-nuclear sentiment.”

The aircraft became the center of controversy when W. Burr Bennett Jr., a B-29 veteran, wrote to the editor of the Air Force Association’s “Air Force” magazine, telling what he knew about the planned exhibit. An article written in 1994 unmasked the museum’s intention to use the Enola Gay as a “prop in a political horror show.” That and future articles drew the attention of Congress, the media and the public.

In August 1994, more than two-dozen congressmen sent a letter to the secretary of the Smithsonian condemning the exhibit. Five months later, 81 congressmen called for the resignation of Harwit. Eleven days later, the Smithsonian scrapped the exhibit; Harwit resigned on May 2, 1995.

In June 1995, the forward section of the fuselage as well as the flight deck and bomb bay were put on display at the Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C., chronicling the particulars of the mission without editorializing or portraying the bomber’s mission as the launch pad of the nuclear arms race. Four million people visited the exhibit before it closed in May 1998.

The pieces were then returned to the Garber facility. When the museum opens its new Udvar-Hazy Center, scheduled for late this year, the Enola Gay will again be displayed prominently.

As for Paul W. Tibbets Jr., he is enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame. His awards and decorations include the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, European Campaign Medal, Joint Staff Commendation Medal, American Defense Service Medal, WWII Victory Medal, Air Force Outstanding Unit Award and American Campaign Medal.

Tibbets, 88, has often looked back on two very important events in his life, his experience in dropping Baby Ruth candy bars on unsuspecting race fans at Hialeah and nearby beachgoers in 1927, when he was the passenger of barnstormer Doug Davis, and his role in the dropping of “Little Boy” on Hiroshima. He says that the mission to Hialeah was definitely “more exciting” than the one to Hiroshima. Why?

“There is nothing to match the thrill of a 12-year-old boy’s first airplane ride,” he says.

A Rendezvous With History (part 1)

For more information, visit www.theenolagay.com.