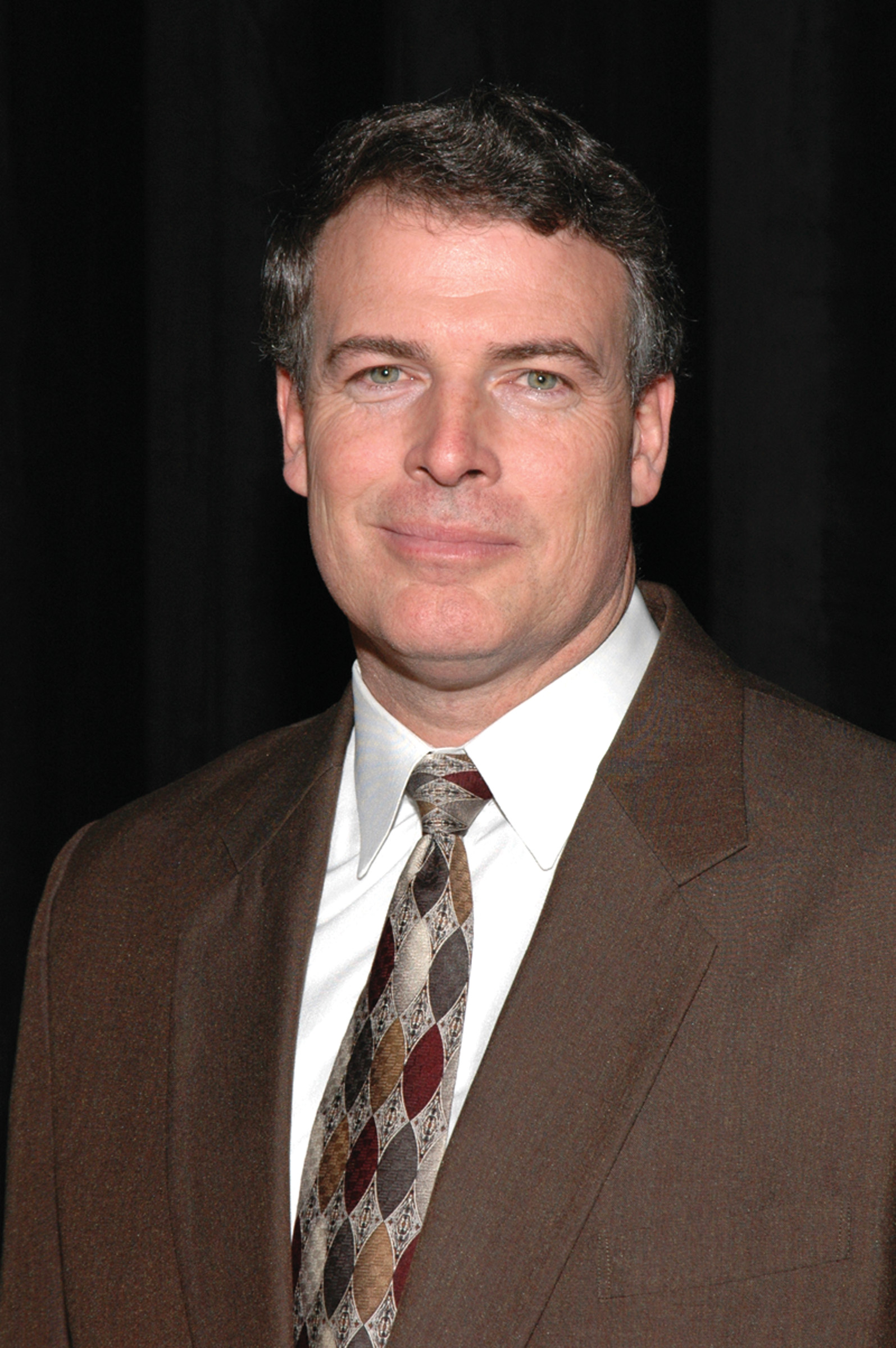

By Karen Di Piazza

Following a lifelong career in the Air Force, Col. Peter J. Bunce is the new president and CEO of the General Aviation Manufacturers Association.

On April 1, Peter J. Bunce, 47, started his new career as president and CEO of the General Aviation Manufacturers Association. GAMA’s board of directors announced its selection of Col. Bunce to lead GAMA in February, but they had to wait out his retirement from the U.S. Air Force.

GAMA, an international trade association headquartered in Washington, D.C., represents over 50 of the world’s leading manufacturers of general aviation aircraft, engines, avionics and related equipment. Members also operate fleets of aircraft, fixed based operations, and pilot training and maintenance training facilities.

Nine months ago, Ed Bolen, GAMA’s CEO and president of nine years, left the organization to become the president and CEO of the National Business Aviation Association. Can Bunce step away from his lifelong military régime and lead GAMA in a civilian fashion?

Twelve days into his new job, Bunce had no doubt that he could execute GAMA’s initiatives on Capitol Hill—where ideas often become stuck in bureaucratic red tape.

“Actually, with respect to my military background and my new position with GAMA, there are more similarities than differences,” he said.

During his last military position at the Pentagon, where he was the director of Air Force Congressional Budget and appropriations liaison, he worked with members and staff of the House and Senate.

“I spent quite a bit of my time on Capitol Hill on Air Force matters associated with the annual defense appropriations bills,” he said. “Life will be a little different; I was part of the executive branch, but now I’m representing industry both to the executive branch and the legislative branch.”

Additionally, Bunce spent five years as the Department of Defense’s representative to the International Council of Air Shows’ board of directors and safety committee. Through daily contact with members of Congress and congressional staff, he advised senior Air Force leaders on committee actions and pending legislation as well, where he expressed, “he was familiar with red tape.”

“Before GAMA, I was an advocate for both the Federal Aviation Administration’s approving processes and supporting the FAA as they supported GA,” he said.

What’s Bunce’s management style like, and can his business philosophy meld into the civilian world?

“I’d like to think of myself as someone who is somewhat of a visionary—someone who has a long-range plan and then takes the steps necessary to achieve the plan,” he said.

He’s also someone who values personal relationships.

“If I have a choice between sending someone email or having a face-to-face meeting, I’m going to take the latter,” he said.

He said that’s how you get things done in Washington D.C.

“It’s important to build friendships, build trust and be a straight shooter,” he said. “I’ve always said I don’t have a hidden agenda. I try to find common ground in areas that I can bring people together on, make decisions and move forward.”

He said part of his management style is to delegate, not micromanage.

“Because of my military career, I’m the farthest thing from a micromanager,” he said. “If someone is that way, they’re inefficient as leaders.”

Bunce joked that probably his biggest challenge now is learning all new acronyms.

“As we all know, the military has millions of them; now I have to learn all of the GA acronyms,” he laughed.

He certainly doesn’t need lessons on how to fly aircraft. While in the Air Force, he flew various types of planes, including F-15s and A-10s, and commanded numerous military flying units. At times, he commanded units that had as many as 22 F-15s, 90-plus A-10s and numerous C-130s. Under his command, all the pilots and maintenance personnel reported to him.

“Commanding flying units was probably the most rewarding element of my entire Air Force career,” he said. “Once you have aviation in your blood, there’s no leaving it.”

Walking down memory lane, Bunce talked about his position as an Air Force pilot commander, and why his “aviation addiction” focuses on people, too, not just the sheer force of jet engines.

“It was all the pilots and all the maintenance guys,” he said. “To be able to see the young enlisted people, some of the older chiefs and the crusty old guys that you always looked up to, and being able to command all of that, and focus on combat readiness and training was a dream come true.”

He said he made his decision to become a fighter pilot at an early age.

“I decided in seventh grade that I was going to join the Air Force Academy,” he said. “I always felt lucky that I could fly some absolutely awesome machines.”

After Bunce graduated from the academy with a BS in international relations and a master’s degree in international affairs, he participated in an international affairs fellowship program at Harvard University.

His love of aviation isn’t exclusive of the military. He has his commercial pilot’s certificate with multi-engine and instrument ratings.

“I owned a Piper Cub; while I attended piloting school for the Air Force in Texas, I would fly my Cub over ranches when I had free time,” he said. “I also flew several World War II vintage aircraft, whenever I got the chance. I’ll still fly anything I can get my hands on.”

Bunce started flying when he was very young.

“Nine months old, to be exact!” he said. “My aunt, who operated a GA airport near Milwaukee where I grew up, also owned and operated 11 airplanes, so I was always in a plane with her. I don’t actually recall the moment or how old I was when I soloed because my aunt and all her friends let me fly.”

He said his aunt flew with him a lot of the time in a Luscombe.

“Luscombes are aluminum, side-by-side tail-wheelers, which are a lot of fun to fly,” he said. “I used to go to the airport so I could hang around planes, and I was getting lessons in them before I was old enough to see over the control panel. I also flew in a T-Craft (Taylorcraft), a Cub and a Champ (Aeronca).”

Bunce said because he loves GA so much, he’s excited to focus his efforts on fostering the growth, safety and security of GA at GAMA.

Bunce’s top priority—FAA certification issues

James. E. Schuster, chair and CEO of the Raytheon Aircraft Company, was elected chair of GAMA for 2005, after serving as vice chair and chair of GAMA’s Security Issues Committee.

Although reduced FAA services have caused serious delays of certification of new aircraft and components, Bunce is confident there will be a turnaround and that the FAA, through Congress, will boost its sagging record of slow certifications.

“This is my top priority, working with the government to speed up the process; new aircraft certification is the linchpin that enables us to move aviation forward,” Bunce said. “I think something that’s achievable and actionable this calendar year is trying to push the ball over the goal line on certifications.”

Original equipment manufacturer members of aircraft and components are hopeful of that. However, the certification process has been at a snail’s pace; added to the FAA’s workload, with its diminishing staff, the agency faces an onslaught of new aircraft type certifications. OEMs of very light jets and start-up air-taxi companies that have invested into this segment of the market had forecast returns on investment to kick in long before this.

Bunce says when the FAA holds up aircraft systems and development, it significantly immobilizes aviation overall, but GAMA has a program set in motion to mitigate further certification delays.

“Within our organization, we have developed ‘PAC,’ which means process, accountability and communications,” he said. “For the last two years through PAC, we’ve gotten together with the FAA to have a series of meetings in which issues of certifications are laid out on the table. We’re trying to identify how the FAA and our corporations in industry would work together to set an actionable certification milestone plan. Through PAC, we’re trying to implement some very specific guidelines for accountability, where it’s a cooperative effort—accountability on the FAA’s part, and accountability on industry’s part.”

Bunce explained PAC was trying to set two different schedules at the same time. One is setting milestones that meet a schedule period, and the other is meeting milestones within the FAA’s certification schedule.

“You have to hold everyone’s feet to the fire to achieve that,” he said. “If you don’t, those milestones will slip. As we know, time is money, which significantly impacts when new products reach the market. With the rapid advance of technology right now, that can be directly equated to making systems faster, cheaper and better. The ‘better’ translates to safety.”

He said that through new technology aircraft safety and training programs have improved, and the better industry’s training is, the more we’ll be able to reduce accidents. Bunce agrees that new technology presently seen in many of today’s aircraft has outsmarted the human; therefore, the entire training process must be notched up. But training criteria alone isn’t enough.

“Training has to be approved by the FAA, too,” he said. “It’s not just the issue of getting the FAA to process new aircraft certifications and systems at a faster pace. It’s getting the whole GA market up to speed at a faster pace.”

Bunce said that aircraft manufacturers have stepped up to the plate and have started to offer better training—something that wasn’t happening before.

“I think that our OEMs have recognized the need for tailor-made training of their aircraft, not just so someone can be competent taking off and landing, but they’re providing tailored training of how that corporation or how that individual is going to use the aircraft,” he said. “The more training that we can provide, in a systematic approach, will further improve aviation safety.”

GAMA isn’t sitting back waiting to see if the FAA is going to cooperate; it’s urging Congress to provide oversight of the FAA, to ensure that appropriated funds are spent properly and for their intended purpose. In recognizing budget pressures, GAMA said it was crucial that the FAA and industry implement strategic initiatives.

Bunce said some of those initiatives include delegation of authority, to leverage limited resources and improve the efficiency of the certification process. The FAA reported that budget pressures have forced reduced services in many areas, including aircraft certification. However, in FY05, Congress fully funded the FAA’s budget request for personnel.

Consequences of slow or no-go certification

Bunce said because of FAA budget woes, it has downsized its Aircraft Certification Office through attrition of its engineering staff, hence reducing its level of services it provides.

In recent talks, GAMA reported that the FAA has committed to support existing certification programs already in process. The bad news is that due to waning FAA staffing, new certification projects are being evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and possibly delayed in order to determine which projects will be supported and which will be put on hold.

According to the FAA, each new project will be held until it’s determined what resources are necessary to support the program and whether the FAA will wait to begin the project. That policy doesn’t bode well for GAMA or OEMs, but the situation could worsen; the FAA will not provide manufacturers with specific criteria for the evaluation, which leaves manufacturers without any guidance on when or how to start new product development.

“A policy like this will cripple the aerospace industry’s ability to bring new products and technologies into a competitive marketplace,” Bunce said.

GAMA reports that the aerospace industry makes the largest trade surplus contribution of all U.S. industrial segments—$32 billion in 2004. To remain competitive in the world market, the federal government must maintain its level of services and support to the U.S. aerospace industry.

Bunce predicts substantial economic hardships on OEMs if the FAA doesn’t provide guidance on the types of certification programs it’s able to support in a timely manner. Such programs require significant financial commitments and planning before the FAA becomes involved. If the FAA doesn’t maintain its level of services and support, manufacturers have threatened to launch certification programs in a foreign country—one that’s able to support its projects, and sees the value of promoting aerospace. Moreover, because of bilateral trade agreements, GAMA’s leadership maintains foreign certificated aircraft and parts validated in the U.S. aren’t likely to be affected by FAA delays.

Bunce, coming from an environment full of “bureaucracy,” warns patience isn’t only a virtue; it’s needed right now. He said there’s one thing he’s found with any bureaucracy.

“It’s the nature of the beast; things don’t happen at lightening speed like they can with private industry,” he said. “With the right amount of direction, the FAA can apply some practices that private industry has found to create better efficiency. That’s our aim.”

But can certification issues be resolved before 2006?

“I think the certification issue is achievable by the end of 2005,” Bunce said. “But there are still big issues to tackle with the FAA. One of which is the revenue stream for the FAA. As we lead up to reauthorization of the FAA next year, one of the biggest things we want to look at is making sure that there’s a common vision. We need a common vision of what we want things to look like. We don’t want people to get their positions so set in stone that people won’t put ‘all’ of their issues out on the table.”

Bunce warns that hasty decisions could thwart inroads that GA industry has made.

“People have to understand that Congress is starting a series of hearings and Marion C. Blakey, the FAA administrator, is talking about the funding challenges that are in front of her,” he said. “That’s why I’m saying it’s important that facts are known, and cards are put out on the table with full visibility before any positions get solidified. The whole purpose of a long-term reauthorization from Congress is that we’ll all be able put our hats on and look into our crystal balls to come to a common working ground. What we don’t want to do is stifle innovation and technology that goes into the cockpit, which translates into safety.”

GAMA’s security overview

Ronald L. Swanda, GAMA’s senior vice president of operations and interim president before Bunce’s arrival, responded to an unclassified, confidential, government aviation security overview published March 1 by saying he didn’t agree with “press reports” that would have the reader believe that nothing has been done regarding GA security.

“Those allegations couldn’t be farther from the truth,” said Swanda, a 22-year veteran employee of GAMA. “And the rest of the aviation industry works closely with all federal security agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigations and the Department of Homeland Security.”

Following enactment of the General Aviation Revitalization Act in 1994, Swanda was the staff-lead and primary author of GAMA’s “Piston-Engine Aircraft Revitalization Plan.”

He serves on NASA’s Aeronautics Research Advisory Committee and the FAA’s Research and Development Advisory Committee, and is the past chair of the Transportation Research Board’s Business Aviation Committee.

“The report referenced in the press is a result of industry working with federal security agencies in sharing threat information,” he said. “In fact, this assessment was completed at the request of, and released to the civil aviation community. The actions the GA industry has taken since 9/11 have been well coordinated with all federal security agencies.”

He said that last year the Transportation Security Administration issued GA airport security guidelines that tailored security around a broad range of even small GA airports.

“The government recognized that one size doesn’t fit all in security; it determined for GA that a set of government-endorsed, industry best practices would be best suited,” Swanda said.

Bunce said Swanda had done an outstanding job at GAMA, and that he’d continue to tap his expertise in GA.

“The statement he made that GAMA will continue working with the federal government to improve GA security, based on risk threat-vulnerability assessments, is correct,” Bunce confirmed.

Bunce said that we shouldn’t just focus, though, on GA security.

“I think we need to look at aviation security as a whole, not just one aspect of ‘general aviation’ security,” he said. “I think only a few people would tell you that our aviation environment in this country is less safe than it was before 9/11. Many things have happened that have made security and flying safer. I’m not just talking about what you’d find at a commercial airport, but rather the awareness that’s on any flight line where people are paying attention to what goes on—and they are paying attention.”

Bunce said that since 9/11, regulatory changes in GA have tightened up. He said “you just can’t wander around” without someone noticing.

“Today, passenger screening is mandated by the TSA, which involves charter aircraft weighing more than 12,500 pounds,” he said. “In addition, ‘all’ non-U.S. citizens seeking flight training in the U.S. on aircraft weighing more than 12,500 pounds must first undergo a TSA background check.”

The TSA is requiring each flight student to register with the agency once official flight training begins. Foreign registered GA aircraft must also be approved by the TSA, and submit a complete passenger manifest before they are allowed into the U.S.

Pilots undergo screening and carry a government-issued photo ID along with their pilot’s license whenever they operate aircraft. The federal government has also searched the FAA’s Airmen and Aircraft registries for persons believed to be security risks.

Moreover, the Airport Watch program that was developed a couple of years ago in a joint effort between the TSA and industry has become extremely successful at GA airports, Bunce confirmed. Every active pilot in the U.S. has received details in the mail about the program.

“I think our government should be credited for having to pass some measures very quickly after 9/11, which made people feel safe on the ground and in the air,” Bunce said. “If someone doesn’t belong at the airport, the federal government is going to know about it; the TSA staffs a toll-free hotline 24 hours a day, seven days a week (1-866-GA-SECURE), so suspicious activity can be reported. We’ve made significant strides in securing GA airports in the U.S. through establishing best practices for GA security, and now we’re going back to reevaluate with the reorganization of the DHS.”

Bunce said because GA media understands the trade, they reported facts about GA security; however, GAMA’s goal is to educate “mainstream” media.

“We want them to call us and get facts before inaccuracies are reported,” he said. “GAMA has the technical expertise that can quickly fill in many details, which can help the media report with a knowledge base.”

Bunce explained that he intends to work in concert with other GA organizations in promoting facts about GA security, such as the NBAA, National Air Transportation Association, Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, etc. He agreed that mainstream media has focused on “possible terrorist” activity, linking it to GA aircraft, without merit.

“The real nightmare scenario, though, is a port, bringing something in on a container ship,” he said. “Someone can do something as low-tech as use a rifle. Those of us who live here in Washington, D.C. saw what happened with the sniper situation; someone using a rifle out of the trunk of their car, basically, changed the lifestyles of an entire metropolitan area.”

He said the federal government is addressing many areas, because terrorists used “aviation,” but not GA aircraft.

“I think the press has latched on to that as the ‘preferred’ mode of terrorism,” he said. “If you look at the security in place today at GA airports, that’s probably one of the more difficult places terrorists could penetrate. But there are no absolutes; you can never say never. What’s important is not overly emphasizing one aspect of transportation security over another.”

He said GAMA’s development of other security guidelines has helped aircraft sellers to identify unusual financial transactions, which could indicate attempts to launder money via the purchase of aircraft.

Gaining access to DCA

GAMA and other trade organizations have been working to ensure that GA has reasonable access to our nation’s airspace and airports—notably the battle regaining access to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

Swanda said GAMA has been working for years now against what has been a handful of private companies and local governments opposed to GA operations for “non-security reasons,” which have begun using security as a pretext for airspace restrictions—namely access to DCA.

Now that Bunce is sitting on the throne, maybe GAMA’s efforts to gain airspace over the Washington area on behalf of GA operations will be more successful. But maybe not as quickly as we’d like.

GAMA had developed a good rapport with David Stone, the TSA chief, who announced in April that he’s stepping down from his post and leaving the agency in June. President Bush nominated Stone’s replacement, Edmund “Kip” Hawley, the fourth boss of the TSA in a four-year period, on May 6. Hawley, a University of Virginia Law School graduate and San Francisco area tech consultant, was one of several people in the private sector who initially helped the Bush administration put the TSA agency together.

Although, Hawley is a member of the FAA’s Air Traffic Services Committee, he has limited experience in aviation, which raises a question: Will Hawley promote restoring GA access to DCA as vigorously as Stone did? Bunce doesn’t seem overly concerned about Stone’s departure from the TSA, and says GAMA will continue lobbying for DCA access.

“We’re pleased with the president’s selection of Hawley as the new assistant secretary for the TSA,” he said. “He has the respect of both the DHS and the Department of Transportation due to his work after the 9/11 event in the creation of the TSA.”

Bunce said the nation needs Hawley’s technical and private-sector background.

“We look forward to working with him and hope to build the same relationship with him as we currently have with Stone,” he said.

He said having access to our nation’s airspace is the only way we can remain a viable link in the nation’s transportation system.

“There are encouraging steps being taken to open the Washington airspace to GA,” he said.” But at the same time, there’s a common sense approach being applied; we have to allow the federal authorities to work through this—to have a common sense approach that balances security and the interest of all aviation.

“As you know, NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) is testing its Washington/Baltimore laser techniques that will warn pilots they’ve violated the Air Defense Identification Zone. As we move on with the ground-based VWS (visual warning system), as it’s being tested, in time, it might remove some of the restriction.”

Such testing is none too soon. On May 11, a Cessna 150 flew into the Washington, D.C. flight restricted zone. By the time the Cessna was three minutes away from the nation’s Capitol, fighter jets escorted the plane down. The White House and its staff went back to work within minutes, after its evacuation.

Bunce, not held back by a few faux pas, agrees critics are using this as an excuse to keep GA away from DCA.

“The incident shows that the system works!” he said. “The pilot, apparently, didn’t have authorization to enter the Washington, D.C. FRZ, and appropriate actions were taken quickly. This system is built upon the actions taken since 9/11, to protect the sensitive locations within the FRZ. We don’t want to see something happen that would put more restrictions on GA because something took place that we could’ve prevented with better vigilance. Failure isn’t an option.”

In mid-February, GAMA urged support for legislation introduced to develop and implement standards for the resumption of GA flights at DCA, and Swanda said congressional pressure would be necessary.

“We believe we’re close to seeing the first phase of GA access to DCA, so congressional support is critical at this stage,” Swanda commented.

Swanda said if access to DCA were a phased approach, continued congressional pressure would be vital to insure all incremental steps move forward.

Bunce confirmed he’s in agreement with Swanda; a phased approach with a common goal to gain access to DCA is long overdue.

GA shipments looking good

Although the FAA and the TSA are hurdles to jump over, GA shipment billings looked good at year-end in 2004.

James E. Schuster, GAMA’s elected chair for 2005, said that perhaps the most significant indicator of the health of the GA industry is airplane billings.

“Total industry billings rose 19.1 percent in 2004, to $11.9 billion,” he said. “These are the third highest billings ever for our industry—just 14 percent below the 2001 peak.”

Last year, GAMA noted industry billings were highly correlated with changes in the U.S. gross domestic product, and that an improving economy would overall give GA a shot in the arm. Schuster said that’s still the case.

“The U.S. GDP rose 4.4 percent in 2004, and our billings rose 19.1 percent,” he said.

Schuster is an executive vice president of the Raytheon Company and chair and CEO of the Raytheon Aircraft Company, and previously served as GAMA’s vice chair and chair of GAMA’s Security Issues Committee.

“You may recall that 2003 was the worst year for GA aircraft billings since 1998,” he said. “To have billings rise so quickly from that is an indication that GA is becoming an even more significant part of the world’s air transportation system.”

During GAMA’s Annual Industry Review and Market Outlook in mid-February, Schuster said that bonus depreciation, coupled with the continuing growth of the U.S. economy, was a turning point for industry in 2004.

“Since 1994, when the General Aviation Revitalization Act was enacted, manufacturers of GA aircraft have produced and shipped over 25,000 fixed-wing aircraft worth more than $101 billion,” Schuster said.

He added that direct revenues derived from GA in the U.S. are over $41 billion annually. He also said that he’s rallying support against GA user fees.

“GAMA’s top legislative priority in 2005 is opposing new aviation user fees and any increases in aviation fuel taxes that represent more than GA’s ‘fair share,'” he said. “Imposing new user fees would curtail the GA industry’s current rebound and could actually decrease the amount of revenue collected.”

For more information, visit [http://www.gama.aero].

L to R: Ronald L. Swanda, senior vice president of operations, and James E. Schuster, chair, welcome Peter J. Bunce, GAMA’s new president and CEO.