Raymond Loewy has been recognized as the greatest pioneer of industrial design consulting and is still remembered for the adage that summed up his approach to design: “Never leave well enough alone.”

At the age of 15, Loewy designed, built and flew a toy model airplane that won the James Gordon Bennett Cup. Around that time, he also designed and patented a model plane powered by rubber bands. Having subsequently sold the rights to the Monoplane Ayrel to a company that marketed it across France, Loewy learned that “design could be fun and profitable.”

With the money he earned, he was able to study at the Universite de Paris and later at the Ecole de Lanneau, where he received an engineering degree in 1918. During World War I, he served in the French army as a second lieutenant. After his demobilization, he traveled to America in 1919. Arriving in New York, he was amazed by what he later described as “the chasm between the excellent quality of American production and its gross appearance, clumsiness, bulk and noise.” He initially found work as a window dresser for Macy’s, Saks Fifth Avenue and Bonwit Teller.

From 1923 until 1929, he enjoyed a “pleasant but superficial career” as a fashion illustrator for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair, among others. In 1923, he also designed the trademark for the Neiman Marcus department store. Loewy eventually left the fashion world to set up his own industrial design office in New York in 1929. Always a self-promoter, he had a card printed that read, “Between two products equal in price, function and quality, the better looking will outsell the other,” and sent it to everyone he knew. Soon afterwards he received his first response; he redesigned the casing of Sigmund Gestetner’s duplicator machine, using modeling clay to create a sleek form. He later employed this technique to great effect for his automotive designs. The resulting machine (which lasted in form for over 40 years) not only looked better but, thanks to its simplified form, was also easier to manufacture and maintain than earlier models.

In 1932, Loewy designed his first car, the Hupmobile, which was less boxy than existing automobiles. His improved, tapered model of 1934 featured innovative integrated headlamps and predicted the streamlined forms for which he later became so famous. That same year, Loewy also designed the Coldspot refrigerator for Sears Roebuck, which was the first domestic appliance to be marketed on the strength of its aesthetic appeal; contemporary advertisements invited consumers to “Study its Beauty.” The Coldspot was also alluring to customers because its improved design had reduced its cost of manufacture; that was reflected in its competitive retail price. The product was a great commercial triumph and won first prize at the Paris International Exposition of 1937.

In 1934, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York displayed a mock-up of Loewy’s glamorous design office (streamlined chrome furniture and sleek black floor surfaces), thus illuminating his rise in status from product designer to celebrity industrial design consultant. From 1935, Loewy was commissioned to re-plan several large department stores, including Saks Fifth Avenue. During this period he was also designing aerodynamic locomotives, such as the K4S (1934), the GG-1 (1934) and the T-1 (1937). In 1937, he published a book entitled “The New Vision Locomotive.” The S-1 steam locomotive became famous for its landmark design standards.

In 1946, he remodeled coaches for Greyhound and in 1947, designed his innovative Champion car for Studebaker, which was a precursor of his later European-styled Avanti car (the only automobile to be exhibited in the Louvre), also for Studebaker. Not only could streamlining make transportation look more appealing, it also often improved performance and efficiency because of the effect of aerodynamics. Loewy regarded the design of a casing or sheath as an opportunity to allow a machine or a product to express itself. Unlike so many modernists who allowed form to be completely dictated by function, Loewy balanced engineering criteria with aesthetic concerns in order to achieve what he believed to be the optimal solution. His designs included rounded corners and simplified outlines; he made important contributions to the design of such products as electric shavers, toothbrushes, ballpoint pens, soft-drink bottles, radios and product packaging. Perhaps his best-known design was that of the Coca-Cola bottle.

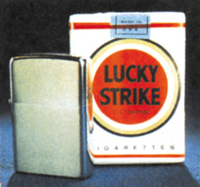

Loewy also became celebrated for his corporate identity work, and in particular for his repackaging of Lucky Strike cigarettes (1942). His prestigious clientele included Pepsodent, the National Biscuit Company, British Petroleum, Exxon and Shell. By 1939 his designing office had branches in Chicago, Sao Paulo, South Bend and London. In 1944 he founded Raymond Loewy Associates with five other designers; it became the largest industrial design firm in the world.

Loewy’s flamboyant lifestyle included at various times country homes outside Paris, in Southern France, Mexico, Long Island, and Palm Springs, as well as luxurious urban apartments in Manhattan and Paris. Image and style was very important because—in combination with a keen business sense, a highly developed imagination, and a rich design talent—it was an important element in generating a sense of excitement about the new profession of industrial design itself. Industrial design was tested by fire during the Great Depression; in a shrinking market, the product “designed” by an industrial designer would win out over an otherwise similar and equal product.

In 1949, Loewy became the first designer to be featured on the cover of Time magazine; his picture was accompanied by the memorable caption, “He streamlines the sales curve.” That same year, Loewy expanded his operations and founded the Raymond Loewy Corporation to undertake architectural projects. During the 1960s and 1970s, he worked as a design consultant to the U.S. government, mostly redesigning—with sleek and simplified lines—Air Force One for John F. Kennedy, and designing interiors for NASA’s Apollo and Skylab orbiters (1969-1972). Always putting the consumer first, Loewy’s MAYA (Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable) design credo was crucial to the success of his products. Undoubtedly the greatest pioneer of streamlining in the 20th century, Loewy clearly demonstrated that the success of a product depends as much on aesthetics as it does on function. Few design consultants have been as influential or prolific as Loewy—nor as misunderstood. Although he was a styling genius, he also skillfully improved the des

ign of many products and pioneered numerous design innovations. Significantly, Loewy glamorized the practice of design and in so doing raised the status of industrial design as a whole as a profession.

Life Magazine selected Loewy as one of the 100 most influential Americans of the twentieth century. It’s interesting to note that his continued vitality and international influence was demonstrated by his being retained as a major industrial design consultant in the 1970s by the government of the Soviet Union—this as he entered his eighties.