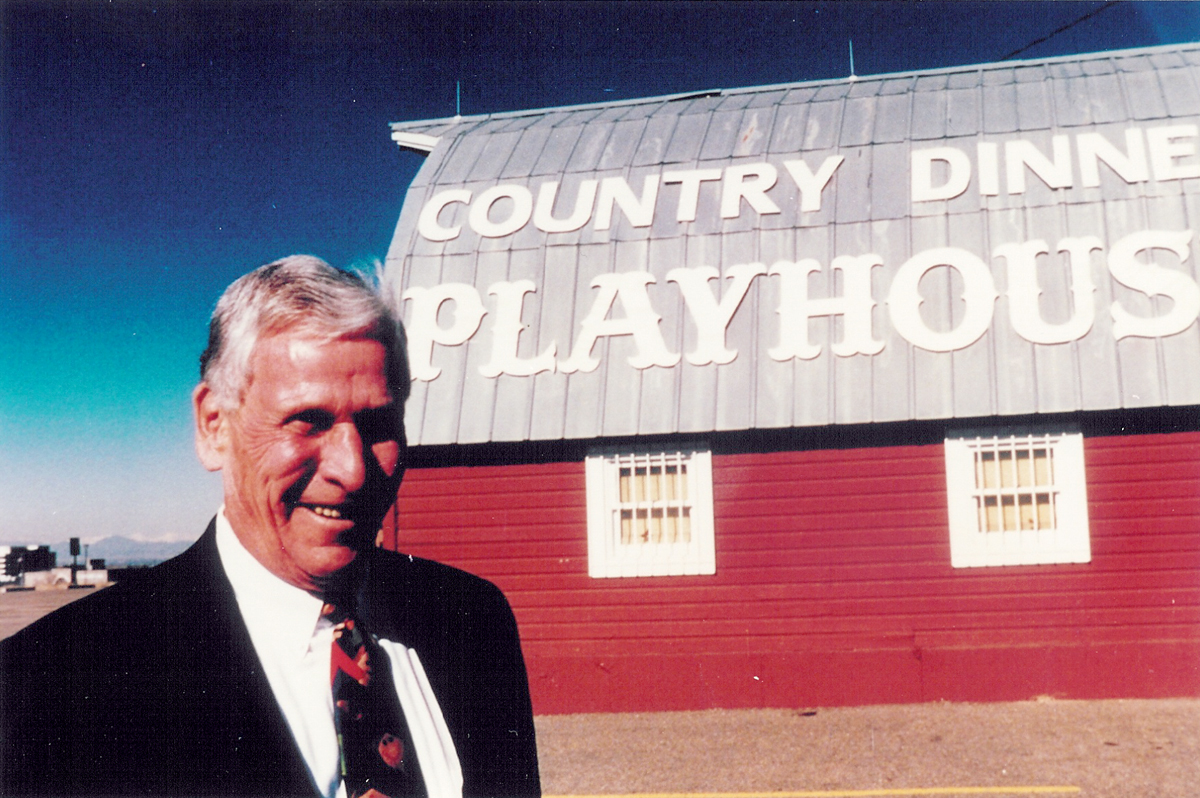

Sam Newton founded the Country Dinner Playhouse, a popular mainstay in Colorado for three and a half decades.

By Di Freeze

Sam Newton, the founder of the Country Dinner Playhouse, a popular mainstay in Colorado for three and a half decades, died July 21 of complications from a fall. He was 87.

In 2000, Airport Journals interviewed Newton at his office on the Country Dinner Playhouse grounds. The walls provided visitors with a glimpse of his life, including pictures of his father standing in front of Haskins Brothers Soap Company, a prize steer, Newton with President George H.W. Bush, and a model of a Flying Fortress (complete with sound), given to him by his daughter.

At that time, he reminisced about his childhood, his military experience and the path he traveled after his service to his country. Born in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1920, his memories included days in Omaha, playing at the soap factory owned by his father, J.P. Newton, and his uncles, which manufactured Blue Barrel laundry soap.

An athletic teenager, Newton was on the all-state football team. After graduating from Central High in 1939, he headed out to a YMCA camp in Granby, Colo., where he discovered a love for Colorado. After accepting an invitation from a friend to ride down to Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Newton found himself enrolled in classes there, where he adding flying to his list of achievements, via the Civil Air Patrol program.

World War II was on the horizon. Preferring not to be drafted, Newton set his mind on joining the branch of the military that singer Tony Martin had joined—the Navy. Newton’s goal was to be a Navy pilot. He had no problem passing the tests in Denver, but there was one requirement he didn’t meet. He weighed 240 pounds, and the Navy set its restrictions at 185.

Newton asked recruiters when they’d be back. Finding out that it would be three months, he went on a strict diet and made daily runs up and down Monument Creek. Three months later, weighing 182 pounds, Newton showed up on a Saturday to take the tests again. The recruiters, however, were snowbound in Greeley, unable to make the trip to Denver. On Monday, Newton drove back to Colorado Springs and signed up with the U.S. Army Air Corps.

After training to fly a B-17 Flying Fortress, he went to Salt Lake City, where he would pick up his crew and head off to Alexander, La. But a chance encounter with a Phi Gamma Delta fraternity brother from college would change his direction. Bert Stiles and Newton would finagle a WAC to assign them to the same B-17 crew.

Inspired by singer Tony Martin, Sam Newton intended to join the Navy. However, complications resulted in his signing up with the U.S. Army Air Corps.

In March 1944, Newton and Stiles, both the same age, arrived in Bassingbourn, England, at the Eighth Army Air Corps Bomber Station. Once in England, Newton was told that their crew could pick a group, but not the 91st Bomb Group, which was, in essence, the “country club” of the European Theater of Operations. However, the 91st had lost many of its crew, as well as aircraft, and Newton and his crew did become part of that group. Newton’s crew would now be the 401 Squadron, 91st Bomb Group.

Since Stiles had only flown single-engine aircraft, Newton was assigned as the pilot, in most cases, and Stiles as his copilot.

Newton, who would first fly Cool Papa, and later, Times A-Wastin’, recalled a busy airfield where there were always five missions forming, one on each corner and one in the middle. For missions, the crew would be woken at 2 a.m. for breakfast and a briefing. Once at the briefing, the pilots were told about the length of their flight and where they’d meet up with the fighters that would accompany them.

“We called the fighters ‘little friends,'” Newton said. “Often, if the little friends were chasing German aircraft, the bombers would become temporarily friendless.”

Newton and his crew would fly over enemy occupied Europe, and make three trips over the German capital of Berlin. Newton said it was always easy to tell when they were over Berlin, because the flak would be particularly rough.

Newton’s second and third trips over Berlin were the worst. On the second trip, their Fortress was hit, damaging the plane’s tail surfaces and causing difficulties for Newton as he piloted the plane back to England. On the third trip, the group in front of Newton’s received the heaviest attack.

“We could see enemy fighters and Forts going down all over,” he said. His crew reported six kills that day (damaged and/or destroyed.)

In June, Newton piloted one of the 11,000 aircraft that bombed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, 11 minutes ahead of the initial assault troops. He recalled the cloud covering over the German defenses and the empathy he and his crew felt for the group troops below. After dropping their bombs, they headed home, watching alertly as a flight of German ME-109s headed the opposite direction. Newton also clearly remembered crossing the English Channel, and hearing Gen. Eisenhower’s speech over the airwaves.

On June 20, Newton’s crew attacked oil refineries at Hamburg. On that mission, Newton watched a friend, flying off his wing, be shot down.

“I told my CO that I didn’t ever want to go back there again,” Newton recalled. But the next day he went back.

“Later, we were sitting down eating, and someone dropped a chair,” he recalled, grinning. “I jumped from being so tense.”

The experiences also caused Newton to experience many nightmarish evenings.

After training to fly a B-17 Flying Fortress, Sam Newton was assigned to the 401st Squadron, 91st Bomb Group, at the Eighth Army Air Corps Bomber Station, in Bassingbourn, England.

That year, Newton and Stiles both received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with oak leaf cluster. In late summer of 1944, Stiles took time off to write a book about their experiences in the European Theater. He dedicated “Serenade to the Big Bird” to 1st Lt. Albert F. “Mac” McCardle, who was killed in action on May 1, 1944, while flying Cool Papa when Newton and his crew were in London on leave.

After 31 missions, Newton headed back to the States. He eventually joined an air transport command, which would take him all over the world. Stiles, with the same number of missions, decided to transfer to a fighter squadron. On Nov. 6, 1944, while Stiles piloted his P-51 in a chase over Hanover, Germany, he was shot down.

Newton received an honorable discharge from the services in 1946. He headed back to Colorado College for a short time before deciding that a college education wouldn’t get him the piloting job he wanted. Thousands of pilots were vying for the same positions.

Newton had taken Christmas vacation in California, and, after leaving school, decided to move there. He unsuccessfully tried to get a job with the Flying Tigers airline, and then received an offer to transport a C-54/DC-3 on a leg from Los Angeles to Omaha. The job would have paid him $240 a month, but he declined, in hopes of working for Monarch Airlines.

After sending out 200 resumes and being told almost as many times that he didn’t have enough experience, he moved back to Colorado Springs and began driving a bread truck. He later married Hilda Brickell, a sister of a friend. The couple moved to Denver, where they lived in a diminutive $50-a-month apartment near Colfax Avenue.

Newton worked for a while for J.J. Monahan, a company that made portable plastic lungs, before becoming co-owner and vice president of Western Merchants Wholesale Company, which put nonfood items in supermarkets. His work with the company allowed him to sit in a cockpit once again, as he would often fly the company’s Aero Commander.

Avionics Engineering

Newton’s love for aviation led to his purchase of a Cessna 182 in the early 1970s. He based it at the newly established Arapahoe Public Airport (now Centennial Airport). He also purchased an avionics company from aviation pioneer Oxy Chanute. He changed the company name to Avionics Engineering of Englewood and moved it from its location at Clinton Aviation, APA’s only fixed based operator, to a new hangar he had built. The only other hangars at the airport then belonged to developer George Wallace and Gov. Roy Romer.

A second avionics company followed—Avionics Engineering of Denver, based at Stapleton International Airport—and he also bought a Cessna 337. Although he would eventually sell the planes as well as both companies, his son Stephen would remain with the company located at Stapleton through different owners, including Combs-Gates, American Airlines and Bombardier, for the next 20 years. He later started his own company, Centennial Instruments, located near Centennial Airport.

“The Musical Drunkard”

Sam Newton met and married Hilda Brickell after moving to Colorado Springs, Colo. The couple later moved to Denver.

It was a game of golf, in a roundabout way, that led Newton to theater. After golfing in New Orleans in the late 1960s, Newton stopped in Dallas to visit friends Bob and Mary Boren. They accepted an invitation to the Windmill Dinner Theater to see “The Musical Drunkard.” Both men were impressed.

“I thought this would be a great thing for Denver,” Newton recalled.

After deciding to found their own dinner theater, the Borens and Newtons acquired land south of Arapahoe Road, near Centennial Airport. Shortly after founding the Country Dinner Playhouse, the men hired Bill McHale as producer/director.

McHale began his career in the theater as an actor/singer, becoming resident leading man in Milwaukee at the Fred Miller Theater, the forerunner of the Milwaukee Repertory Company, playing alongside Harvey Korman in comedies, and actresses such as Betty White. He also starred in musicals, and in the early 1960s, joined Bob Simpson, a choreographer who started putting reviews around the country called “The Hits of Broadway.” A tour in Denver at the Top of the Park, at the Park Lane Hotel near Washington Park, resulted in a move to Denver for McHale in 1963.

With a cast he brought with him, he opened the “Highlights of Broadway” at the Flaming Pit Theater/Restaurant in Cherry Creek. He met Sam Newton and Bob Boren while working with the Barn Dinner Theaters, a conglomeration of dinner theaters located in the south and southeast U.S.

The Country Dinner Playhouse, a theater-in-the-round that provided 470 people with a perfect view, opened on April 14, 1970, with a hearty country style meal spread on a red-and-white-checkered tablecloth. Frontier Airlines employees and guests paid $5 a head for a private showing of “Come Blow Your Horn.”

The theater’s $20,000 “magic stage” was designed to go up after each act and come back down out of the ceiling for the next one, to the awe of the crowd. At the time, there was only one other hydraulic stage in the country, in Chicago, which came up from the basement.

That first show, however, the stage went up at the end of the first act, but wouldn’t descend once the sets and actors were in place for the next act. They soon discovered that the deadman’s switch had stuck, and began the process of carrying the props from the stage down to the floor. The last two acts were performed with the poles up. The incident prompted a journalist reviewing the play to write, “Country Dinner Playhouse opening has its ups and downs.”

For three months, Newton ran the company, working seven days a week, until Boren was able to move out from Dallas to take over. The following year, Newton and Boren approached the management of the Windmill Dinner Theaters (formerly the Barn Dinner Theaters), a conglomeration of theaters selling franchises, about buying the Windmill Theater in Scottsdale, Ariz. They were told that in order to purchase the one in Arizona, they would have to buy the whole chain, which included dinner theaters in Houston, Dallas and Fort Worth. They also founded the Derby Dinner Theater in Clarksville, Ind., across the river from Louisville, Ky.

David Lovinggood started with the company in 1971 as general manager, before becoming executive vice president. Other key team members were Robert E. Buffington, who worked for the company since it opened, becoming vice president and general manager in 1995, and his wife, Joan.

Sam and Hilda Newton founded the Country Dinner Playhouse with friends Bob and Mary Boren in 1970. Shortly after founding the theater, they hired Bill McHale (left) as producer/director.

In later years, Boren moved back to Dallas and ran the Windmill Theaters and the Derby Dinner Playhouse. Newton, serving as CEO and president of the company, looked after the Country Dinner Playhouse, with McHale producing and directing shows for all of the theaters.

After a show opened in Denver, it would go on to Louisville and the other theaters, with the nucleus of the cast traveling. While a part of the Windmill chain, actors came and went, including Pat O’Brien, Van Johnson, Cyd Charisse, Phyllis Diller, Dorothy Lamour, Ann Miller, Mickey Rooney, Gary Berkoff and Bob Crane.

To open each show, the Playhouse created the Barnstormers. The idea for the group came from McHale’s experience with Barn Dinner Theaters, where the warm-up cast was called the Haymakers. The apprenticeship program allowed those involved to learn their craft while making a living.

Directed in later years by associate producer Paul Dwyer, the Barnstormers evolved into singing and dancing hosts. Many of the Barnstormers found jobs across the country as professional touring musicians and in other capacities, including Lee Horsley, who, after being cast in several Playhouse productions, went on to star in “Matt Houston” and “Paradise” on TV; Patsy Ann Calmes, who played in the musical “My Three Angels” at the Playhouse in 1970, and is better known as actress Morgan Fairchild; and Ted Shackelford, well known for his role as Knots Landing’s Gary Ewing.

In the early days, the Country Dinner Playhouse kept apartments for the out-of-state actors and held national auditions from New York and Los Angeles for the various theaters. Later, it ran audition notices in local dailies.

For years, the Country Dinner Playhouse was the region’s only year-round professional Actors’ Equity theater. The theater won several awards, including one for its production of Kopit and Yeston’s “Phantom of the Opera.” In all, McHale produced and directed 188 musicals, before leaving CDP in April 2000. When he retired, David Pritchard came on board, eventually becoming president and COO.

By the mid-1980s, all of the other dinner theaters had been sold, except the Country Dinner Playhouse. In 1995, the Newtons and Mary Boren sold the theater to Lovinggood, the Buffingtons and John Rutter, the majority owner. Rutter ran his own certified public accounting firm for many years, in addition to being the accountant for the Playhouse, and served as chairman and CEO of the Playhouse.

Newton retired in 1996, but kept an office in an outbuilding on CDP property. Complications for the theater started in 2002 when Rutter died, resulting in a lengthy ownership struggle between his wife, Eileen, and Pritchard, CEO at the time, over Rutter’s share, valued at more than $1 million. Two years later, Lovinggood completed his purchase of the theater from Eileen Rutter, gaining 65 percent ownership. The remaining 35 percent belonged to the Buffingtons. The group named Dwyer producer and artistic director.

Newton’s September 2005 sale of the 5.82 acres that the theater occupied, to Uhlmann Offices Inc., of Sherman Oaks, Calif., for $3 million, seemingly led to insurmountable problems. In May 2007, stunned “Evita” cast members arrived at the theater to find the doors padlocked and a note posted by Lovinggood stating the theater had run out of money. In the note, he said that negotiations with the theater’s landlord had been underway for several months to no avail. “Without a lease in place, we cannot sell season tickets,” he said. “This has put us in a position of having no funds to continue operation of this business.”

During 31 missions, Sam Newton flew Cool Papa and Times A-Wastin’. Artist Greg Valace later featured Times A-Wastin’ nose are on a fuselage in his B-17 Freedom collection.

That evening, cast members performed in the parking lot in the rain, for those who had purchased tickets for the evening’s performance.

At the time, CDP was the second largest theater in Colorado and one of the longest running professional union dinner theaters in the country. During its storied history, cast members had entertained more than 5 million theatergoers with more than 220 productions.

In September 2008, more than 170 former actors, artisans and longtime patrons gathered at Denver’s Hilton Garden Inn for an emotional Country Dinner Playhouse reunion. Those gathered included original Barnstormer Tony Greaves, as well as Thaddeus Valdez and Clarissa Hope Stranske, from the final cast of “Evita.” The evening included entertainment, testimonials and a tribute to McHale.

Giving back

Over the years, Newton enjoyed elk hunting, fishing in Alaska, trail riding, sailing, bicycling and morning swims (his love of swimming led Newton to develop the Skyline Acres Swim and Tennis Club with friends). A father of two and grandfather of four, he divided his time between a home in Cherry Hills Village, a yacht in San Diego and a cattle and horse ranch in Empire.

The gentleman rancher bought the grand champion steer at the National Western Stock Show two years in a row in the late 1980s. He then donated them back to the stock show for resale to earn money for college scholarships for children who raise stock.

From his office at the Country Dinner Playhouse, Newton conducted business, much to do with the nonprofit work he did for different organizations, including the Easter Seals Foundation. Newton once served as president of the foundation. A pavilion at the Easter Seals Camp bears the name “Sam & Hilda Newton Pavilion,” honoring a large donation they presented to the organization.