By Terry Stephens

The City of Renton has honored 101-year- old aviation pioneer Clayton L. “Scotty” Scott with a special monument at Renton Municipal Airport. The monument recognizes his 79-year flying career, as well as his association with the airport since 1928.

When famed Pacific Northwest aviation pioneer Clayton L. “Scotty” Scott turned 101 in July, the City of Renton, Wash., honored him with a special monument at Renton Municipal Airport. The monument recognizes his 79-year flying career, as well as his association with the airport since 1928.

Renton Mayor Kathy Keolker declared July 15 as Clayton Scott Day, and then joined the spry, smiling aviator and a crowd of his admirers at the airport to unveil his brass statue, dubbed “Pathfinder,” at a special birthday barbeque in his honor. The statue was the culmination of a year of planning, designing, funding, building and coordinating with Renton and airport officials. The monument was called “Pathfinder” in honor of Scott’s years of flying as a Boeing test pilot, but also for his early, pioneering cross-country flights at a time when navigation aids were primitive at best.

The Museum of Flight joined Scott’s close friend Bill Jepson in spearheading the project and the museum foundation contributed funds.

“When the concept to install a permanent monument at this historic airport to honor Clayton Scott and his fellow Pacific Northwest aviation pioneers was brought to the museum’s board of trustees, they wholeheartedly agreed with it,” said former astronaut Bonnie Dunbar, the museum’s president and CEO. “A campaign to raise the necessary funds began and Scott’s friends and family responded quickly and generously. The result is one of the finest tributes to our state’s early aviation roots that can be found.”

Scott attended the celebration with Jepson, a Mercer Island neighbor, who also designed the sculpture, raised money for the statue and directed the construction. At the birthday party, Keolker and Dunbar offered congratulations to Scott on his flying career and talked about the historic importance of the airport.

The only other appropriate honor they might have given Scott would have been to name the airport after him—but they already did that last year for his 100th birthday. Today, Renton Municipal Airport—the airport where Scott built much of his flying career—is also known as Clayton Scott Field.

Pathfinder Park, a new landscaping project at the entrance to the airport, will be finished later this year. It will feature Scott’s impressive statue showing him in the helmet, goggles and leather-jacketed flying gear he wore in the 1920s and 1930s. Next to him is a 16-foot-tall pole with direction signs in the shape of propellers, pointing to destinations throughout the world. At the top are the words “Clayton Scott Field” and a rocket pointed skyward, engraved with “Space – 50 miles.”

The airport opened in 1922 as Bryn Mawr Field, under the private ownership of John and Allen Bloom. In 1941, the Navy took over the field and built the first of the Boeing factories that were to produce B-29s. The existing runway for the giant bombers was constructed in 1943.

In 1947, the city bought the airport back from the government to provide an airfield for Boeing’s production of C-97s, CK-97s, C-135s, KC-135s and commercial 707, 727, 737 and 757 airliners. Boeing has built more than 11,000 aircraft at the airport, including the 5,000th model of the 737 that was delivered to Southwest Airlines last February. Over several decades, as a test pilot for Boeing, Scott flew most of those planes and many others, including the B-17, B-47 and B-52, which he called “the Cadillac of Boeing planes.”

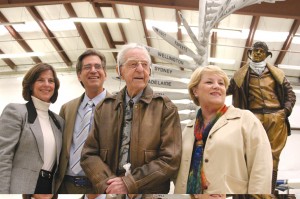

Clayton Scott, in front of the “Pathfinder” statue unveiled in his honor, with L to R, Museum of Flight CEO Bonnie Dunbar, sculpture designer Bill Jepson and Renton Mayor Kathy Keolker.

Scott’s long and varied flying career left his own unique imprint on the airport and on Pacific Northwest aviation. He was one of the first airmail pilots on the West Coast, flew for eight years as William E. Boeing’s personal pilot, was a test pilot for Boeing for 25 years and ran his own business at Renton Field for 52 years.

Flying first captured Scott’s interest on his uncle’s farm in Pennsylvania, the state where Scott was born in 1905. A barnstorming flyer set his Curtiss Jenny down on the farm in 1920, offering rides to all comers. Only 15, Scott didn’t get his flight, but when the plane was settled in for the night, he climbed into the cockpit, moved the control stick around and watched the tail flaps move up and down.

In 1922, after his family had moved to Oregon, Scott found a new opportunity for a flight when a barnstorming pilot flew into Seaside. Then 17, Scott and his girlfriend pooled their money—his $7 and her $3—for their $10 ride aboard a Jenny. The exhilarating experience of that flight from the beach was never forgotten, but it was four years later before Scott had a chance to learn to fly.

After graduating from high school, Scott studied bookkeeping, and then completed training as a mechanic at Adcox Auto and Aviation School in Oregon in 1925. The next year, he tried a new field, starting as a teller at Portland’s U.S. National Bank. One of his regular customers was aviation pioneer Vern Gorst, who had just founded Pacific Air Transport. Using ship searchlights to guide his mail planes over the Siskiyou Mountains, his planes made the first complete airmail run between Los Angeles and Seattle. When Gorst came into the bank, Scott always tried to make contact with him.

“I made it a point to take him to a booth and talk to him,” he said. “One day, I told him I would like to work for him.”

By October 1926, Pacific Air Transport employed him. Not as a pilot yet, but as a mechanic, a station attendant at Pearson Field in Vancouver, Wash., and a driver for Gorst’s black Ford Model T truck—which curiously had a large white “T” painted on its roof, so it was clearly visible from an airplane. West Coast airmail at that time started out on a train from Seattle to Portland, where Scott would pick it up each morning and deliver it to Pearson Field. When weather was too bad for flying, however, Scott would head south with the mail to Medford, Ore.

“When the weather cleared, the pilot would take off and follow the highway until he saw my truck and could find a farmer’s field where he could land,” Scott recalled in an interview in 2005. “I would pull over, give him the mail and then turn around and go back to Pearson Field.”

Within weeks, Scott was taking flying lessons from Gorst’s pilots, soloing in an OX-5 Waco after less than four hours of instruction. By February 1927, he had earned his commercial license. When Pacific Air Transport was bought by William Boeing in 1928, becoming a division of Boeing Air Transport, Scott followed Gorst to Seattle as operations manager for Gorst Air Transport, which included the Seattle Flying Service and the Bremerton Air Ferry. Soon afterward, while flying a 1917 Travel Air biplane for Gorst’s Seattle Flying Service, bad weather made Scott the first pilot to land at the yet unopened Boeing Field, today’s King County International Airport.

Scott also was the first pilot to take a commercial transport across the Gulf of Alaska, from Ketchikan to Cordova. That flight was memorable to Scott for more personal reasons, too. One of the passengers on that trip was a schoolteacher, Myrtle Smith, who not only became the first woman passenger on that route but also became Scott’s wife in 1934. That was the beginning of a 65-year marriage that ended with her death in 1998.

During the years when Scott was flying between Juneau and Cordova, he was once stranded for two days on the beach at Ice Bay, Alaska, when the engine of a Boeing Model 204 pusher-prop, civil flying boat “swallowed a valve” and forced him to land in the surf, where waves soon destroyed the stricken plane. Gorst sent another seaplane to rescue Scott and his mechanic.

It was in British Columbia that Scott first met William Boeing, at a gas pump in Carter Bay in 1931. Scott was fueling his Keystone-Loening Air Yacht while Boeing was refueling his twin-screw diesel yacht, the Taconite, built by Boeing Aircraft of Canada in 1929.

“He (Boeing) walked over to look at the airplane, and we casually got to talking to each other,” Scott recalled. “He was a really good fellow, very congenial. He enjoyed fishing, and when he was out on a trip he was just a normal person—no airs or anything.”

Two years later, when Boeing wanted a personal pilot to fly his B-1E Model 204 to carry supplies and mail to the Taconite, he called Scott. The two men became lifelong friends. In 1933, Boeing arranged for Scott to join Boeing Air Transport as copilot for the Boeing Model 247, the nation’s first airliner, between Portland and Salt Lake City.

This 1929 photo of Clayton Scott helped to inspire the theme of a commemorative statue unveiled in July for the entrance to the newly named Clayton Scott Field.

His first flight, from Portland to Salt Lake City, was more than a bit unsettling for Scott. As he completed the preflight checklist with the pilot, he had more questions than the ship’s captain could answer. Frustrated by the questions, the pilot said, “Hell, I don’t know. I was just hired yesterday.”

Later on that flight, a night trip up the Columbia River Gorge, Scott was startled when the pilot asked him to take over the controls, and then disappeared into the cabin to have coffee with the only passenger on board.

“I thought, ‘This is a great way to run an airline,'” Scott said.

After 1934, when federal legislation forced the breakup of Boeing’s United Aircraft and Transport Corp., Boeing left the aviation business. Scott continued as his personal pilot, flying Boeing’s Douglas-built Dolphin amphibian, Rover, and later, his DC-5, often with celebrities aboard. One flight’s passengers included Howard Hughes, accompanied by Ginger Rogers.

After eight years as Boeing’s personal pilot, Scott was named chief production test pilot for the Boeing Co., spending 25 years there until his retirement in 1966. In 1941, he first flew Boeing’s SeaRanger, a “flying boat” design. But only a single prototype was built before the escalation of World War II, which shifted Scott’s flying time to checking out production B-17s before they were released to the military. By 1943, Scott had accumulated more hours in the Flying Fortress than anybody else, in more than 1,000 different planes. During those years, he also spent hours test-flying Boeing’s secret new high-altitude bomber, the B-29.

Scott’s first jet flight was in the XB-47 bomber, out of Boeing’s Wichita, Kan., plant. He recalled that the plane “had so much performance and speed.”

“It was my first experience with anything like that,” he said.

Later, he tested 707s and 727s, B-52s and KC-135s, in a career that accumulated more than 8,000 hours of flight time.

“Every new airplane was an improvement over the last,” he said. “Each one was a mighty fine ship to fly.”

While still working for Boeing, Scott started his own business in 1954, at the airfield that now bears his name. The Jobmaster Co., first headquartered in a hangar he built himself, was next to the airport’s seaplane ramp into Lake Washington. He parleyed his early flying experiences with seaplanes into a company that adapted floats to a wide variety of aircraft, including the Piper Aztec, Dornier DO-28, de Havilland Beaver, de Havilland Otter and Cessna 195.

After he retired in 1966 from Boeing to work fulltime at Jobmaster, the company hired Scott to build a replica of the aerospace firm’s first airplane, the B&W seaplane, for the company’s 50th anniversary. Today, the plane hangs as a prominent display in The Museum of Flight.

In 2005, for a celebration of his 100th birthday, he flew a twin-engine Aerostar into Boeing Field for the event, conceding to share the flight with a copilot. He had agreed to quit flying solo when he was 98. A highlight of the celebration, with scores of guests and dignitaries from the aviation world, was yet another award.

Pacific Northwest FAA Regional Administrator Douglas Murphy presented Scott with the prestigious Wright Brothers Master Pilot award, reserved for aviators who have “demonstrated exceptional competence and commitment to excellence by logging 50 or more consecutive years of safe flight.” At the event, Murphy noted that Scott’s pilot’s license, No. 2155, made him America’s oldest active pilot in 2005, with the lowest-numbered active license.

Scores of organizations have honored Scott, including the Federal Aviation Administration, Experimental Aircraft Association, National Aeronautic Association, OX-5 Aviation Pioneers, Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, Quiet Birdmen and the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. Now, at the airport named for him, there’s a new monument on display to honor his unusually long and active aviation career.