“Mustangs on the Prowl” depicts P-51s from the 55th Fighter Group doing what they liked to do best after being relieved from escort duty, which was heading down to a lower level to look for targets of opportunity.

By Larry W. Bledsoe

Mention Robert Taylor to non-aviation art buffs and you’ll probably get a response such as, “Robert who?” Or, if they were born before 1950, “Do you mean the actor?” But mention Robert Taylor to any aviation art collector and they’ll know exactly who you’re talking about–the Englishman who’s probably the best known aviation artist in the world.

On Nov. 2, 2005, Taylor was the guest of honor at the Military Gallery’s United States office in Ojai, Calif. He was there to kick off sales of his latest two prints and the book, “Robert Taylor Air Combat Paintings, Volume V.” The print, “Little Friends,” plus a signed copy of the book are sold together as a limited USAAF collector’s edition. Likewise, the print, “Top Cover,” and a signed copy of the book, with a different dust jacket, are being sold as the limited RAF and Commonwealth edition.

There’s a remarkable story to go with “Top Cover.” Taylor wanted to depict a Spitfire Mark XIV in this painting. During his research, he contacted an Australian Spitfire pilot who had flown that particular Mark Spitfire. After discussing with the pilot eight different incidents that Taylor might depict, he chose an event that occurred on Oct. 6, 1944. The flight of Spitfires from 610 Squadron led by Tony Gaze was returning from a mission when they picked up a damaged Halifax over Holland that was limping home.

Needing to know more about the Halifax, its squadron and its markings, Taylor did additional research and found that the plane was from the 462 Squadron and that its pilot was Ted McGindle, who now lives in Australia. McGindle had written a book about his wartime experiences in which he told about this particular mission.

“Little Friends,” from Robert Taylor’s USAAF collector edition, shows 20th Fighter Group Mustangs escorting the flak-damaged B-17 “Bit-O-Lace” home after a raid on Kiel, Germany.

The Halifax was returning from an attack on the synthetic oil plants in Germany. Two of the crewmembers had been ordered to bail out while the skipper struggled to keep the plane in the air. Other crewmembers on board were too seriously wounded to escape. In fact, one of the wounded men had been bandaged with his own parachute. Knowing they didn’t have a chance if he bailed out, McGindle decided to try to get the crippled bomber home.

As they approached the coast of Holland, he saw ahead of him a wall of flak. Unable to avoid the lethal flak barrage, he felt his plane and the surviving crewmembers were doomed. Just then two Spitfires dove past his plane and went down and suppressed the flak batteries, allowing him to get safely through. In his book about his wartime experiences, he wrote that he never knew who the specific Spitfire pilot was that saved his life and that of his crew that day.

As it turned out, Taylor’s research made it possible for the bomber pilot to finally meet the Spitfire pilot who had saved him. What’s even stranger is that they both lived in Australia, and only about 50 miles apart.

Since camouflage paint schemes and aircraft markings changed throughout the war, over the years Taylor has built up an extensive resource library, including photos of World War II aircraft. He researches to get the right markings for the time period being depicted in a painting. This includes not only how the aircraft was painted, but also what model of aircraft flew the mission. Hence, the Mark XIV Spitfires and the Halifax depicted in “Top Cover” accurately depicted the aircraft used on that mission.

The Spitfire became a symbol of the heart of a nation. “Top Cover,” from the RAF & Commonwealth edition, shows Mark XIV Spitfires escorting a damaged Halifax from 462 Squadron home in 1944.

He does use creative talents as needed to tell the story. For example, the flak-damaged B-17 in “The Mighty Eighth–Coming Home” was based on a wartime photo that shows that plane with a new rudder. Based on that, he used artistic license to depict it the way it was shown in the painting.

Taylor tries to focus on one painting at a time, and spends about two months on each one. First, he determines the subject, and then does a lot of reading and research, while envisioning “mind pictures” of what it will look like. He actually “sees” the whole scene with the airplane in motion before he paints it.

There are exceptions to his rule of focusing on one picture at a time. Taylor recalled that one time while on a commercial flight he saw a particularly striking cloud formation, with the sunlight at just the right angle. He took a photograph of it, and when he got home, blocked it in on canvas. He doesn’t know yet what aircraft or event he’s going to depict on it, but every once in a while he pulls it out and adds something to it.

In the Pacific, the U.S. Navy was turning the tide of war against Japan with the introduction of the Grumman F6F Hellcat. “Hellcat Fury” shows fighters from VF-6 making a low-level attack against the Japanese airfields and their fleet anchored in Truk Har

He uses a lot of models because they give him the proper perspective, both in aircraft detail from a certain viewpoint and for the correct proportions of the aircraft as seen from a distance. This is essential for depicting aircraft in formation and in different positions during aerial combat. He has used models for probably two-thirds of his paintings.

He does many pencil sketches first, to visualize the composition and tone factor. Some of these amazingly detailed sketches appear in each of the five volumes of his works. According to him, if the composition looks good in shades of gray, then it’s going to look good in color.

After he’s satisfied with the composition he’s sketched, he then does a concept drawing on the canvas to visualize the sky, the horizon, etc. Then he starts painting the background and from there layers it up with detail.

Taylor uses only oil paints. He does use acrylic only for the primer on the canvas, because it prevents future cracking. If an oil paint is used for the primer, the painting will crack as the painting ages. Acrylic doesn’t. This is why the “old masters” in museums are cracked. Taylor always paints on canvas, not cotton or any other material. He paints in the traditional way and buys only the best oil paints.

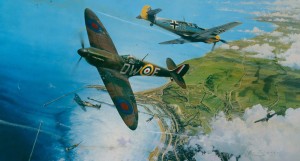

The Battle for Britain” depicts a Spitfire from 610 Squadron making a head-on attack against an Me 109 over the port of Dover during the summer of 1940.

Using white primer backlights the picture. As the painting ages, the oil disappears and the painting becomes more translucent. The paintings of the old masters in museums are better than when they were painted because of this change. Consequently, he said, “I will never live to see my paintings at their best.”

He mixes colors on the canvas rather than on the palette. For example, painting red on blue while the blue is still wet has a startling effect. He likes pure natural colors and only quality paints. He likes cobalt and ultramarine.

Taylor doesn’t use black paint. He uses either ultramarine or burnt sienna to get the feel he wants. In his paintings, he’s always striving for perfection. He said he never achieves it, but always tries to make the next one the perfect painting. It’s this driving force that makes him grow as an artist and keeps him painting.

He has a secret signature he adds to each painting, but he wouldn’t reveal it.

“If I told you what it is, then it wouldn’t be a secret, would it?” he said mischievously, but firmly.

Taylor is constantly learning about painting. Several techniques he now uses, he’s learned in the last 10 years. Always striving for perfection and looking for something new keep him on his toes.

How does he know when a painting is finished? He builds up a painting, adding details as he goes, until he reaches a point when he knows instinctively that it’s finished.

The scars of war

In 1992, the Military Gallery published two Taylor prints that showed the 8th Air Force, “The Mighty Eighth-–Outward Bound” and “The Mighty Eighth–Coming Home.” The latter print, shown here, shows a battle-damaged B-17 returning home after a raid.

A question people often ask Taylor is, “How do you know all this information about World War II?” He was born after the war in Bath, England. Bath had been heavily bombed during the war, and the scars remained long after. Taylor’s childhood home was within a hundred yards of some of the bombed-out buildings.

He remembers, as a youngster of about 5, being baffled when he saw a building with a fireplace visible from the outside. What he didn’t realize then was that the house had been bombed. The room was destroyed and all that remained was the wall where the fireplace was. It was those memories and that of the people he grew up with, who had lived through the war, which burned in his heart and mind an overwhelming interest in World War II.

When asked about his favorite plane, Taylor pauses over a difficult question. On the one hand, it would be the Spitfire, and on the other, the Mustang. He said the Spitfire looked like a thoroughbred, and not a fighter. The Mustang, however, looked like what it was–a fighter.

No matter what he’s painting, he carefully crafts each of his works. He said there’s a difference between a crafted and a prepared painting. You have to know how light reflects off a plane and how it affects clouds and landscape. It’s the background that makes the plane live. He makes the planes living and breathing; they must meet that standard.

On D-Day, General Doolittle, 8th Air Force, flew a P-38 over the beaches of Normandy to witness firsthand the progress of the invasion developing below, and then reported back to General Eisenhower. “Doolittle’s D-Day” depicts this unprecedented flight by

“If you want to understand good aviation art, you should look at the works of classical painters and educate yourself as to what is good art and what isn’t,” he said. He, himself, loves the French Impressionists and the Dutch Masters.

Taylor has been painting aviation works professionally since about 1978. He believes he’s completed about 500 paintings and that more than 300 have been published as limited editions.

Taylor says he’s an artist who’s an aviation enthusiast, not an aviation enthusiast who’s an artist. As evidence of his worldwide popularity, more than half his limited edition prints that have been published by Military Gallery are sold out at the publisher. Of those available on the secondary market only, all have increased in value, many have doubled in value, and some have appreciated far more.

Taylor is recognized as one of the foremost aviation artists in the world, but he has a humility that makes him a joy to talk with and to interview. For him, painting aviation art is a labor of love. This soon becomes apparent as you listen to him talk about painting and aviation. His enthusiasm is contagious.

For information on obtaining Robert Taylor’s artwork, contact Larry Bledsoe at (909) 986-1103 or lwbcpf@aol.com, or visit [http://www.bledsoeavart.com].