|

By Di Freeze and Deb Smith

It’s late in the afternoon. Legendary triple ace Robin Olds leans back in a well-worn, brown leather chair, surrounded by mementos of his history. He adjusts his suspenders, raises a glass of scotch and looks out the window of his home in Steamboat Springs, Colo. The reclining sun illuminates his large frame and strong jaw. With a sense of purpose, he takes a drink—almost as if in homage to those with whom he served during his 30-year military career. He sits back, smiles and then takes his two guests on a journey they’ll never forget. At this reflective time in his life, the man credited with 17 official aerial victories as well as the success of “Operation Bolo,” gives a colorful verbal account of not only his Air Force career, but also the making of Air Force history. The early years Maj. Gen. Robert C. Olds, a World War I fighter pilot, met his future wife Eloise in Honolulu, Hawaii. Their son Robin Olds was born there on July 14, 1922. Eloise Olds would die when their son was 4. Maj. Gen. Olds and his military career would dominate the child’s life. By the time Olds had celebrated his first birthday, his father was sent back to the mainland. Robin Olds spent his boyhood in Hampton, Va., and grew up on Air Corps bases. Olds’ father served as an aide-de-camp to controversial air power zealot Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell. “I suspect that’s where my dad gained his attitude and aggressiveness about the need to recognize the potential of air power,” recalled Olds. “In those days, Dad was part of the Army Air Corps. The old guys in the Army and the fleet admirals considered the airplane something of a toy. They didn’t see any potential for it in naval and military power. In their minds, they were way back in the Civil War. My entire youth was spent on military bases, in the shadow of men in the old Army Air Corps who were fighting, at risk of their careers, for recognition of air power.” Mitchell’s controversial tactics included talking the Navy into letting him bomb captured German battleships. In 1921, he successfully sank various ships, including the Ostfriesland, a stationary German WWI battleship off Virginia’s coast. Robert Olds, a colonel at the time, was in command of the pioneering B-17 Flying Fortress 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field, Va. The group’s four squadrons were detached to Gen. Mitchell’s 1st Provisional Air Brigade when the experiments were conducted. “My father referred to LeMay as ‘that fat little lieutenant,'” chuckled Olds. “I’ve always enjoyed his company.” |

|

Growing up in Virginia, Olds quickly fell in love with aviation. He recalled sneaking out to watch the pilots at the base at Langley, and being able to tell the sound of one engine from another before he turned 5. At the age of 8, he took his first airplane ride, in his father’s open-cockpit biplane.

Trying to get to war

Olds’ height of 6 feet, 2 inches, and 205-pound frame made him an exceptional athlete; his wavy hair and piercing blue eyes made him a local dreamboat. He never missed an opportunity to prove his physical prowess, including on the gridiron at Hampton High School.

After graduating in 1939, Olds enrolled at Millard Preparatory School in Washington, D.C. He was boarding there when Hitler invaded Poland, in September 1939.

“Britain and France declared war,” he said. “My father had just moved to Washington D.C. from Virginia, and he came and got me. I hustled myself over to the embassy to join up for the Royal Canadian Air Force. When this man asked how old I was, I lied. He said, ‘Well, we only take them a year older than that. You have to get permission from your parents.’ He gave me a piece of paper and I went home. Late that afternoon, I was sitting there when my dad came home from work. I said, ‘Dad, I’d like you to sign this piece of paper.’ He went right through the ceiling. Back to school I went.”

Olds paused, and then summed up his biggest military struggle in one sentence.

“It was never easy to get to war,” he said. “It was a bigger fight than the fighting!”

Olds considered enlisting and trying to “fight his way” into the Air Corps. However, rules didn’t make that easy either. He continued on the path that had been planned for him and entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on June 1, 1940. The way he looked at it, he’d get a regular commission, fly airplanes and “not work for a living.”

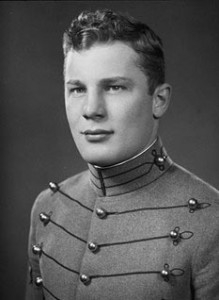

West Point

As a “plebe,” Olds did what came naturally—play football. Again his height, weight and strength made him a tremendous asset to the academy’s lackluster team.

He began his college football career on a squad that had already seen three losses. By the time he graduated, Olds helped lead West Point to victories over The Citadel, Virginia Military Institute, Yale, Columbia and West Virginia.

West Point now had a secret weapon—jersey number 75—which made them a serious contender. In 1942, Collier’s Weekly named Olds “Lineman of the Year” and sportswriter Grantland Rice pegged him “Player of the Year.” He was also selected as an All-American.

Olds played during Earl “Red” Blaik’s first season as head coach and lettered during both seasons he was there. The agile, aggressive young tackle had such an impact on the program he was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1985.

Olds gained from an accelerated program West Point began, which shortened the length of study for those in the upper half of the class to three years instead of four. Those cadets applying to the U.S. Army Air Corps would also receive flight training. Olds was eligible for both programs and applied for early matriculation.

“They wanted a show of hands of those who would like to join the Air Force,” he recalled. “We didn’t know what they had in mind, but up went over half of the hands in my class, to the consternation of the infantry guys. Not all of them qualified, though, because of eyes, mostly.”

In the summer of 1942, those who had shown interest were sent to primary flight training.

“Little groups of us were called in from all over America,” he said. “We finished that in August and went back to West Point.”

They would continue their flight training at Stewart Field, just north of West Point.

“Then it was announced that my class, the class of ’44, would graduate in June of ’43. The class of ’43, which had undergone the same training, would graduate in January of ’44. We had completed flight training, so we graduated with wings—and then went right off to training and to the war.”

Sadly, Olds’ father died in May 1943, at the age of 47, shortly before his son’s graduation from West Point. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold pinned Olds’ wings on him.

World War II

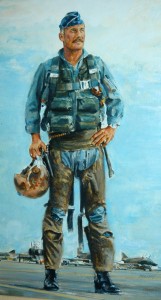

Robin Olds, commander of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing in Southeast Asia, pre-flights his F-4C Phantom. Olds was credited for shooting down four enemy MiG aircraft in aerial combat over North Vietnam.

Now a commissioned second lieutenant, Olds was off to fighter pilot training with the 329th Fighter Group, located at Grand Central Air Terminal in Glendale, Calif. In early 1944, Olds was named part of the cadre that would become the newly activated 434th Fighter Squadron, 479th Fighter Group, at Lomita, Calif.

There, Olds would log more than 650 hours, including 250 hours in the P-38 Lightning. He became frustrated because he was still no nearer to where he wanted to be—in the middle of the action.

“We weren’t getting anywhere!” he exclaimed. “We’d been through the curriculum. They were sending guys over. We didn’t know what the hell was wrong. I found out, somehow, that the Pentagon had put out the word that the ‘precious little West Pointers’ would be sent over only as flight commanders. Well, we were just kids! We were lieutenants. And the numbered Air Force we were in, which ran that part of California, the West Coast, had a rule that the new outfits formed to go overseas would only accept flight commanders who already had a combat tour and volunteered to go back. We were between a rock and a hard place. I got furious! I went in to see my squadron commander, Sid Woods.”

Olds reminisced that in later years, he and Woods became good friends.

“But at the time, Woods was a major and I was a lieutenant,” he said. “He was a great guy. He flew a tour in the Pacific and another couple in Europe. We wound up in the same outfit later on. But he was my boss in that training squadron. So I went in to see him, even though you didn’t socialize with majors. I said, ‘Sir, I want to go on leave.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Lieutenant, don’t you know there’s a war on?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir, that’s why I want to go on leave.’ He didn’t quite understand. I said, ‘Sir, my dad was a friend of General Arnold.’ Arnold was then the head of the Army Air Forces. I said, ‘I want to go to Washington to see General Arnold. I want to go to war. And we’re stuck.” He said, ‘Get out of here!'”

Olds, crushed, went back down the hall and told a classmate, Lt. Al Tucker, what had happened.

“He was a good buddy,” he remembered. “He said, ‘Let’s get in your car.’ We got in the rickety thing and drove into downtown Los Angeles from Ontario, to L.A. fighter wing headquarters. We wandered around the halls and finally came upon the personnel section.”

A gray-haired sergeant was sitting behind a desk.

“A plaque on his desk said ‘Assignments,'” Olds recalled. “We sat down and told him our sad story. He said, ‘You young men really want to go to war?’ We said, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘Where do you want to go?’ We chorused, ‘To England.’ In less than 20 minutes, we had orders for all of us! We didn’t ask our other five classmates—who were all married, except one—if they wanted to go. We just assumed it. We got the orders, and away we went.”

RAF Wattisham

Olds was assigned to the 434th Fighter Squadron, 479th Fighter Group. He arrived at RAF Wattisham, England, in May 1944. Had Olds remained at West Point the full four years, he’d be preparing to graduate and walk the “long gray line” on June 5, 1944. Instead, his unit entered combat in Europe. Within days, he and his squadron were flying a mission over occupied France.

“Our first missions were more like tours,” Olds said. “We were led by somebody from another group who had been over there for quite a while. We flew around, sightseeing. After about two of these, we lieutenants were furious. We wanted to kill somebody! You look down; you see trucks, trains, all sorts of targets—while flying around over France, Belgium, Holland.”

Olds flew an older P-38J Lightning he nicknamed Scat. Each plane he later flew he also named Scat, followed by the sequential order of assignment.

“Scat was the nickname of my West Point roommate,” he said. “Wonderful friend. He wanted to fly so badly, but his eyes… I told him I’d always name my airplanes after him.”

Olds was on Scat IV when his roommate was killed in the Battle of the Bulge.

“I kept naming my planes Scat,” he said. “In between VII, which was my last P-51, and XXVII, there were numerous other aircraft—F-86s, British Meteors, P-80s, 101s, you name it. Everything I ever flew when I was commanding.”

On July 24, 1944, Olds was promoted to captain. Only weeks after his arrival in England, he would achieve his first aerial kill.

Col. Robin Olds (right) stands with his ground crew next to his F-4C Phantom, Scat XXVII. Olds commanded the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing at Ubon Air Base, Thailand, and was credited with shooting down four enemy MiG aircraft in aerial combat over N Vietnam.

“We were rousted out of our sacks very early one morning to go to briefing,” he remembered. “We looked at each other, because it was so early. They pulled aside the curtain. They love to do that—very dramatic. This time, we were going to bomb a bridge in Chalon-sur-Saône, in eastern France. It was behind the retreating Germans. We were trying to make it tough for them to move. I guess that was the plan. But we looked at the takeoff time, looked at each other and realized that takeoff would be before dawn. Why?”

Olds paused dramatically.

“Visualize an airfield in England,” he said. “You had the runways, and around the runways was the perimeter track. The aircraft were parked in hard sand around the perimeter, so taking off a great number of aircraft was a rather intricate process. You had to fall properly into line, in order not to screw things up for the takeoff and assembly. Well, here it was, pitch back, and some idiot ran off the side of the taxiway! That gummed things up for those following. One squadron managed to get airborne. It was somebody in the second squadron.”

Olds was “tail-end Charlie.”

“The very last flight of the last squadron,” he recalled. “All heck broke loose on the radio. I got my guys turned around through the hard sand, and we taxied back and re-sortied ourselves, because I was going to go to the other runway. We arrived, lined up on the runway, and my wingman poured the coal to it. Black as the inside of a cow. We had our landing lights on, so we could see. I was just about to pull back on the stick, and here was another P-38 right in front of me, stuck off the side of the runway.”

Olds said he hauled back on the stick, screamed at his wingman, and felt a big thump.

“I raised the gear,” he said. “I never saw the wingman again. Never saw anybody else. It was pandemonium on the radios.”

So, he switched them off.

“I thought, ‘What the hell? I don’t have anything better to do,'” he recalled. “I flew the mission that the whole group had been planning to fly. I went down, crossed over to Calais, headed through France. I was having a good time. I could hear the first squadron that got airborne. Occasional transmission told me, quite clearly, that they were lost. But that wasn’t unusual for that squadron; they were totally lost.”

Olds had his checkpoints, so he continued to fly.

“Soon, at just the first crack of dawn—just the first light in the east—I saw the river,” he said. “Looked like a ribbon of gold from the glow in the sky. There was this black line going across it, which was the bridge. The whole group was supposed to bomb it. I went and bombed the thing, turned around and left.”

Olds throttled back and prepared to enjoy his flight over the vineyards of France. As he was admiring the view, he looked up and saw two specks.

“I thought, ‘There’s no reason on God’s earth why there should be two specks there that are friends,'” he recalled. “I literally cut them off at the pass. It was a couple of Germans in Focke-Wulf 190s. We had a brief little tussle. I knocked them both down and headed home.”

He explained that in order to get a confirmed kill, somebody else has to see it, or the gun camera film has to prove it, beyond a doubt.

“But we were behind the eight ball there on the P-38,” he said. “The gun camera had been put right underneath the 20mm cannon; every time the cannon went off, the camera jumped, and you couldn’t see anything.”

When Olds filled out his report, he didn’t mention the incident, because he had no way to confirm it.

“Our original group commander had been shot down,” he recalled. “Hub Zemke, a wonderful man, was then set up to lead us—break us in more. He called me over: ‘Captain Olds, come here.’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Did you have an encounter?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Why didn’t you talk?’ ‘Well, sir, the gun cameras don’t…’ ‘You’re the luckiest damn fighter pilot that I ever saw. Tell me, what did you do?’ I said, ‘Well, sir, there were these two Focke-Wulfs, and we fought, and I got them.’ He said, ‘There was an American fighter group overhead that saw the whole thing and they confirmed your victories.'”

Olds said that during the summer of 1944, there was a tremendous amount of interdiction.

“We’d go from marshaling yards, bombing, dive-bombing, marshaling yards, trains, truck convoys,” he said. “Trying to help the Army. It was almost exclusively long, long range. Deep, deep into Germany. Awful lot of airfield strafing. We’d often leave just two guys with the bombers. We’d go down to range all over Germany, looking for ground targets.”

In August, while following a low-level bridge-bombing mission to Montmirail, France, Olds shot down two Fw-190s. On a subsequent mission just a few days later, Olds and his wingman became separated from their group during an escort mission to Berlin.

“I was leading good old D flight, blue flight,” he recalled. “I moved as far out to the left of everybody else as I thought I could get away with; there were enough eyes looking here and there. I wanted to get out where maybe I’d see something first, which we did.”

His eyes noted specks up to their left.

“We knew they were Germans,” he said. “I sneaked over—didn’t bother to say anything to the rest of the outfit. We slowly closed, and all of a sudden, I said to my number two, ‘Drop tanks.’ We dropped the tanks and closed quickly.”

He estimated that the two of them were up against 55 or 60 Messerschmitt Bf-109s. He laughs and says that, under the proper circumstances, two against 60 is “a good deal.”

“Especially if you’re greedy!” he said. “They don’t know exactly where you are, and yet you know where all of them are. You have a tremendous advantage, initially. If they turn to fight, you just run like heck.”

In this case, he closed on tail-end Charlie.

“I had him in my sights and was about to pull the trigger, when both of my engines quit,” he recalled. “In my excitement, I had forgotten to switch gas tanks. I went ahead and fired anyway. I love telling this story to fighter pilots. I’m the only known fighter pilot in the history of aerial warfare that ever shot down an enemy aircraft while in glide mode.”

They got the engine restarted and joined back up with the outfit. He got two more kills that day. He said that shortly after that, they converted from the P-38 to the P-51 Mustang.

“Things sped up then,” he said. “We had much greater range, and it was a better fighting machine at altitude. Better visibility.”

By September 1944, Olds scored another kill. This would be his first in Scat V. Olds would attain his seventh aerial victory just south of Magdeburg, Germany. On the same day, he downed another Bf-109. By February 1945, he claimed three more victories, with two being credited and one downgraded to a “probable kill.”

On April 7, 1945, Olds achieved his final kill of the war while escorting B-24s on a bombing run over a German ammunition dump in Lüneburg. South of Bremen, he saw a pair of Me 262s turn and dive on the Liberators. Olds observed an Me 109 attack the bombers and shoot down a B-24. He pursued the fighter through the formation and shot it down. The engagement had been with the Sonderkommando Elbe, a mysterious German “suicide- ramming” unit.

He achieved the bulk of his strafing credits the following week, in attacks on Lübeck Blankensee and Tarnewitz airdromes on April 13, and Reichersburg airfield in Austria on April 16, when he destroyed six Luftwaffe planes on the ground.

By the end of WWII, Olds had attained the rank of major and was credited officially with 107 combat missions and 13 aerial kills. He was one of the most famous pilots in the world.

Postwar troubles

When Olds came home from the war, he was assigned back to West Point as the assistant football coach under Blaik, his former coach.

“I wanted to be a football coach like I wanted to be a ditch digger,” he said. “I arrived late one afternoon. I was assigned a room in the bachelor quarters. The next day, I was walking to the officers’ mess for breakfast, 50 yards away. Coming toward me was this tall, skinny stick of an officer, with his colonel sleeves, a hat with a grommet in it. I thought, ‘Uh, oh.’ I saluted very smartly.

“I went about two steps when this voice said, ‘You, man.’ I hadn’t been called that since I was a plebe at West Point. That did not please me at all. I turned around and saluted again, and said, ‘Yes, sir?’ He said, ‘Are you assigned here?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘Look at you. How long have you been here?’ I said, ‘Seven hours, sir.’ He said, ‘Well, you’ll find out we do things differently here. That hat of yours is a disgrace.'”

Olds explained that the Army Air Corps members used to take the grommets out and crush their hats. But that wasn’t the end of the colonel’s complaints.

“‘That blouse you’re wearing looks like it’s never been pressed,'” Olds recalled him saying. “There weren’t dry cleaners over in England. Then, he said, ‘Those pants are a disgrace.’ I was thinking. ‘Yours would be, too, if you had to wash them in a can of gasoline.’ He said, ‘Your shirt collar is frayed and that necktie is non-regulation.'”

“I was proud of that knitted necktie,” Olds grinned and recalled the next complaint.

“He said, ‘Those shoes! What are those things you have on your feet?'” Olds recalled. “They were Wellingtons—half boots—which I bought in London.”

Olds was told to report to the officer’s office that afternoon, properly attired.

While he was commander of the 81st Tactical Fighter Wing, Robin Olds’ deputy commander of operations was Col. Daniel “Chappie” James Jr. (right). In Dec. 1966, Olds was reunited with James. The two would lead the unit into the pages of Air Force history.

“As I went into breakfast, I thought, ‘What a welcome,'” he said. “But he was absolutely right. I needed a haircut, too. So I spent that day re-equipping myself. I reported to his office, and he took one look at me and said, ‘Out.'”

Olds reported as assistant coach the next day.

“I didn’t like it,” he said. “Colonel Blaik and his staff were wonderful individuals. But me, as a football coach, uh-uh.”

With a great deal of combat experience, a chest full of medals and little more attitude than when he left, Olds didn’t find the West Point staff very warm or welcoming. It seemed many resented his rapid rise in rank as well as his spectacular accomplishments.

Even as a cadet, Olds wasn’t a huge fan of alumni networking, often called “ring knocking.” He would often hide the fact he was a West Point graduate. In an effort to find a more suitable environment, he sought a transfer.

“When the season ended, I went in to this old colonel’s office,” Olds remembered. “He was a station adjutant. I said, ‘Sir, the football season’s over; I’m ready for my next assignment.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Captain, you’re gong to be here for four years. Get out of here!'”

Olds immediately jumped in his car and drove to the Pentagon.

“I wandered the halls the next day and found a very good friend of mine who was in the personnel section,” he said. “I told him what was going on. He said, ‘Where do you want to go?’ I said, ‘Send me back to Europe. That was fun.’ He said, ‘No, things are a mess over there. We don’t know exactly what’s going to happen or what we’re going to do. Where else?’ I said, “I heard about this outfit out in California that has jets. How about that?’ He said, ‘OK.'”

Thirty minutes later, Olds had his orders. He was reassigned in February 1946 to the 412th Fighter Group at March Field.

“I drove back up to West Point and cleared the base,” he said. “All of this on tiptoes, because I didn’t want anybody to know I was leaving. At 5 o’clock, I knew the headquarters building would be empty. I went in and put one copy of my orders in the middle of that colonel’s desk. I got in my car, drove out the north gate of West Point, turned left and sang all the way to California.”

He recalled his affection and respect for the group commander at March Field: Tex Hill.

“Such a fabulous, wonderful man,” he said. “To this day, he remains one of my closest friends. I knocked on his door, went in and saluted smartly in the best West Point style. I said, ‘Sir, Major Olds reporting for duty.’ Old Tex looked up at me from his desk and said, ‘How in the hell did you get in this outfit?’ I said, ‘Sir, I used pull.’ He said, ‘We have so damned many majors, I stumble over them going to work every morning! Go find yourself something to do until I figure out what to do with you.'”

Olds was assigned to fly the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, the first operational jet fighter used by the Army Air Forces. In August, he joined the first jet aerobatic demonstration team (a precursor of the Thunderbirds). He participated in the first one-day, dawn-to-dusk, transcontinental roundtrip jet flight in June 1946, from March Field to Washington, D.C. That same year he took second place in the Thompson Trophy Race (jet division) of the Cleveland National Air Races at Brook Park, Ohio. In this first “closed course” jet race, six P-80s competed against each other on a 30-mile, three-pylon course.

In 1947, while Olds was based at March Air Force Base, Congress voted to make the Air Force a separate military branch. That same year, Olds met and married Hollywood actress Ella Wallace Raines, with whom he would have two children. After the 412th Group was renamed the 1st Fighter Group, Olds was put into the 12th Air Force headquarters as the personnel officer.

“That wasn’t a bad deal, because, in those days, every request for an individual assignment came across my desk,” he said.

Olds said the first thing he did was assign himself to the Air Command and Staff College, which was located in Florida at that time.

“It’s now situated in Alabama at Maxwell,” he said. “That was wonderful. It was a squadron of officers. Except for the administrative bullshit—teaching you all about stuff you already knew more about than they did—it wasn’t a waste of time.”

However, Olds did miss the flying.

“I came back, and within a month, a request came through for somebody to exchange with the RAF,” he remembered. “Guess whose name was on the desk? I left and spent a wonderful year with the RAF.”

After his 100th combat mission over North Vietnam, his men carry Col. Robin Olds from his F-4 Phantom II.

In October 1948, he went to England under the U.S. Air Force/Royal Air Force Exchange Program. He eventually served as commander of No. 1 Squadron at Royal Air Force Station Tangmere.

“I was the first foreigner that ever commanded a regular British squadron—not territorial, not a reserve, but a regular squadron,” he said. “And No. 1 Squadron at that!”

After that, he went back to March Field.

“They had switched to F-86s by then,” he said.

Olds moved from March to George Air Force Base.

“From the desert, we moved to Griffiths Air Force Base in upstate New York,” he said. “I was selected to take the squadron I was commanding to Greater Pittsburgh Airport, just outside of Pittsburgh, Penn.”

That squadron was the 71st Fighter Squadron, then an Air Defense Command unit.

“The 71st was really the end of the line,” he said. “There was nothing there. A runway, a scraggly building, one little tiny hangar, no supplies. It was a hell of an education, by the scruff of your neck. I wanted to go to Korea!”

He repeatedly applied for a combat assignment.

“My name was taken off every submission I turned in,” he said. “So I turned in my resignation. I was called to headquarters, where a helluva nice general talked me out of it. But I was angry, because I wanted to go to Korea. I was getting a runaround, and I didn’t know why.”

He said he discovered the reason many years later.

“My wife was doing a television show in New York,” he said. “The major backer of the show was a very wealthy man there in New York. The brand new Secretary of the Air Force was a friend of his. We had just become a separate service. This backer did not want me to go to Korea, because he was afraid that Ella would worry herself to death over it, and there would go his money in the television show. I never knew that for 20 years or more. I just thought that somebody had it in for me.”

Olds next worked at Eastern Air Defense Command headquarters at Stewart. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in early 1951. In 1953, he attained the rank of colonel. He served in several staff assignments until returning to flying in 1955, in F-86 Sabres. After serving on the command staff of the 86th Fighter-Interceptor Wing at Landstuhl Air Base, Germany, he commanded its 86th Fighter-Interceptor Group from early October 1955 to early August 1956.

After administrative and staff duty assignments at the Pentagon between 1958 and 1962, Olds attended the National War College. He graduated in 1963. He became commander of the 81st Tactical Fighter Wing at RAF Bentwaters, England, in September 1963. The 81st TFW was an F-101 fighter-bomber wing. Olds commanded the wing until late July 1965.

Olds’ deputy commander of operations was Col. Daniel “Chappie” James Jr., whom Olds had met during his Pentagon assignment. James would go on to become the first African-American four-star Air Force general.

In 1966, Olds received a phone call from the Pentagon that didn’t make him very happy.

“A voice said, ‘You’re on the list.” I knew what he meant,” he recalled. “I wasn’t supposed to know. All secret, secret. But I was on the list to be promoted to brigadier general. I thought. ‘Now, what am I going to do? I don’t want to be a damned general.'”

Olds had a good reason to not want to hear that news.

“The war had just started in Southeast Asia,” he recalled. “I missed Korea, but I wasn’t about to miss that one! I couldn’t tell the Air Force that I didn’t want to be a general because they would say, ‘Fine. Retire. Who cares?’ My boss down in London was not a fighter pilot. Didn’t understand fighter pilots, or the business. He was an old bomber guy with a Missile Badge. I thought, ‘I’m going to make him so angry that he’ll want to punish me. He’ll take me off that list, amongst other things.'”

With pilots from his wing, Olds formed a demonstration team for the F-101. The jet formation acrobatic team performed at various locations in Europe. His boss heard about one aerobatic demonstration—impromptu and low-altitude.

“We put on quite a show,” Olds said. “My boss called me down to London, chewed me out and said I’d never be a general, blah, blah, blah, and shook his finger at me. I counted on a four-star general in Germany, an old buddy of mine, not to let this general court-martial me. My buddy and I had been fighter pilots together. I’m sure that’s what happened. He wouldn’t let my boss court-martial me, but he had to let him punish me. I was taken off the list—bad effectiveness report, stuff like that. He shook his finger at me, wattled his wattles and said, in utmost anger, ‘You are the kind of Air Force officer that ought to be in Southeast Asia!’ I jumped up and said, ‘Yes, sir. Thank you very much!’ I left his office, and he was still shouting at me. That’s how I got to Southeast Asia. Like I said before, getting to war wasn’t always easy!”

Thailand and North Vietnam

L to R: National Aviation Hall of Fame enshrinees Joe Kittinger, Dick Rutan and Robin Olds shared the experience of being combat fighters in Vietnam.

Olds was removed from command and transferred back stateside to Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina, in the summer of 1965. He was still waiting for an opening to be sent to Southeast Asia.

“I didn’t get there right away,” he said. “I had to learn the F-4.”

In 1966, he was assigned to the 4453rd Combat Crew Training Wing, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona (where James was deputy commander of operations), for replacement training in the F-4C Phantom fighter.

Finally, in late September 1966, Olds, 44, took command of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, based at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand.

“I had a wonderful bunch of men, all far more mature than any of us had been back in WWII,” he said. “Three squadrons of F-4s and one squadron of 104s. That squadron was converted to F-4s, so I had four squadrons of F-4s. We never flew missions in South Vietnam. All our missions were north, up around Hanoi. North Vietnam and Laos. Commanding that wing of those men, getting the job done without losing a whole lot of people—that was one of the best years of my 30-year career. They had lost slews before I got there, but I managed to change that.”

The wing had experienced a lack of aggressiveness and sense of purpose. Some have speculated that this is what spurred a rather hasty change of command, placing Olds at the helm. His predecessor flew very few missions in the 10 months he’d been there.

Just two days after Olds arrival in Ubon, the unit lost an F-4 to a MiG-21. It was the first such loss of the war. Compounded by two additional losses, Olds was enraged and became convinced he had to find a better way to get things done.

In a rather unorthodox move, he signed himself up on the flight roster as a rookie pilot and then challenged his junior officers to train him.

“When I arrived, the fleet commanders scarcely flew,” he said. “There was no cohesiveness to the operation. Nobody knew each other. When I arrived at my base, everybody was saying, ‘Who the hell is this? Here comes another damn colonel.’ I got all the pilots together that I could corral. I said, ‘OK. You guys have been fighting this war, and I don’t know a damn thing about it. I expect you to teach me. I’m going to fly tail-end Charlie as you teach me. When I think I’m qualified, I’m going to move up. Soon, I’m going to be out in front of you. Now, teach me, and teach me well, because you don’t want some dumb-shit out in front of you!'”

Olds said he put the burden on them.

“All of a sudden, I had their respect,” he said. “You never demand loyalty. You work like hell to earn it. Your responsibility is to your people. And yeah, the buck stops right here. Soon, they were a happy outfit. They had a boss who gave a damn. A boss who was changing things, leading them, listening to them.”

Olds seemed to like to push the envelope on the ground as much as he did in the air.

“When I got over there to Thailand, it was an absolute no-no to do anything to personalize your aircraft,” he said. “I just shook my head at it. Every pilot is going to have his own airplane. Not that you’d get to fly it all the time, because of the maintenance flow. But you did get to fly your airplane quite a bit. So the crew chief’s name and the pilot’s names went on the airplane. They named the airplanes, too. The inspectors would come over from Materiel Command, Dayton, whining. I’d say, ‘Look, if you don’t like it, just write it up. Report me! Go ahead, it’s your job, I guess. And if I have to answer, I’ll just say, ‘Up yours!'”

Olds was also known for his trademark, well-waxed, non-regulation mustache.

“I grew it over there on a whim,” he said. “Gen. J.P. McConnell visited the base on the 10th of February, 1967. The day he left, I started growing that damn mustache. And the next thing you knew, many of the kids were doing it. It was fun. For the pilots, it was ghastly, because that thing’s crammed under an oxygen mask. But it became sort of a symbol of a rigid middle finger to the Air Force. I said, ‘What are you going to do about it?'”

In December 1966, Olds was reunited with longtime comrade Col. Chappie James. Together—nicknamed “Blackman and Robin”— the two would lead the unit straight into the pages of Air Force history.

Operation Bolo

In early 1967, losses over North Vietnam were increasing. Olds took to the skies—this time in an F-4C Phantom nicknamed Scat XXVII.

Because the Air Force had started to equip its F-105s with radar-jamming pods, the North Vietnamese began aggressively attacking the newer F-4s. The F-4, which first entered service with the U.S. Navy in 1960, had powerful engines and handled well, but it lacked an internal cannon. Its main weapon was its missiles. But often, because of shortage of jamming pods used primarily by the F-105s, the F-4s were left vulnerable and particularly enticing targets.

The Vietnamese People’s Air Force was flying the lighter more maneuverable Mikoyan MiG-21 Fishbed. With aircraft that were heavier, slower and constrained by official U.S. “rules of engagement,” the Americans faced a formidable opponent in the VPAF.

“For us, the laws were very stringent over North Vietnam,” Olds said. “We couldn’t fly over Hanoi, for instance. Couldn’t go near their air bases, even though you could go past and watch the MiGs taking off, and you knew they were going to hit you within 15 minutes.”

Olds came up with an idea. He suggested an “air ambush” to Maj. Gen. William Momyer, Seventh Air Force commander and former commander of the 8th TFW. Momyer agreed and Olds put together a plan designed to draw the North Vietnamese into an aerial trap.

“Operation Bolo,” named after the Filipino martial arts weapon, reasoned that the MiGs could be tricked. By equipping F-4s with jamming pods like those on the F-105s, using F-105 call signs and profiles, the F-4s could most likely dig the MiGs out of hiding.

Olds and his men felt the best way to execute the mission was to plan for a “west force” of seven flights of F-4Cs from the 8th TFW at Ubon and an “east force” of seven flights of F-4Cs from the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing based at Da Nang Air Base, South Vietnam. The mission was scheduled for Jan. 1, 1967, but poor weather conditions pushed it later several hours. At 1500 on January 2, Operation Bolo was underway, with Olds leading the first flight. Asked about heroism in Vietnam, Olds recalled that flight.

“A young airman with a broken leg was working on the ramp at Ubon, at 2 o’clock in the morning, before Bolo,” he said. “He was getting his airplane ready to go. He had broken a leg in a motorbike accident and was on crutches. I said to his flight chief, ‘Sarge, he shouldn’t be out here.” He said, “Colonel, I can’t get him to leave. He’s been here for 18, 20 hours. He’s determined that airplane is going to go.’

“By coincidence, I was assigned the airplane right next to his. When we left that day, there he was, on the concrete with his head on a wooden block, sound asleep with those screaming engines all around. But his airplane went and it got a MiG that day. Now that, to me, is a hero—a hero in the sense of dedication. What a privilege it was to work with people like that!”

Olds arrived over the primary MiG-21 base at Phuc Yen. That day, Olds and his F-4s claimed seven MiG-21s destroyed, almost half of the 16 then in service with the VPAF. It was the highest total kill of any mission during the Vietnam War.

On May 4, Olds destroyed another MiG-21 over Phuc Yen. Two weeks later, he destroyed two MiG-17s, making him officially a triple ace. Over the years, rumors circulated that Olds actually downed five MiGs.

“I asked him once rather he really had the rumored fifth MiG,” said Mike Jackson, former National Aviation Hall of Fame director. “His quote was, ‘I choose not to answer that question.’ He had been told that when he got the fifth MiG, they were going to bring him home. He was a fighter pilot. He wanted to stay with his wing, in the war. Nobody really knows but him if he got four or five.”

In Vietnam, Olds flew 152 combat missions.

Red River Valley Fighter Pilots Association

Early in 1967, Olds hosted a tactics symposium at Ubon. Originally planned as a base “dining-in,: the event was meant to be an opportunity for fighter pilots to discuss what was going on in the air.

“I got permission from General Momyer—he was a great man—to hold a tactics conference,” Olds said. “That was in the fall of ’66. When I first started flying, I realized that none of the guys flying those missions ever talked to each other. We were together in the same piece of sky, but we didn’t know who we were flying with—it was ridiculous.”

Olds thought they should get together face to face and talk over tactics development.

“We held the first meeting at my base, and it was very successful,” he said. “About every two or three weeks, the operations guys would get together. Then we started passing messages to one another every day, about what their intentions were, what ours were, how we worked. Soon, the whole thing came together.”

If it had been a “dining-in,” the entire base would have to be invited. They got around that by hanging a huge banner, which said, “Welcome Red River Pilot’s Association.” Olds’ memory was fuzzy about where the initial meetings were held.

“The first one was at my base, but I’m not sure about the next one. It might have been Quran, but I think it was Takhli,” he said. “The reconnaissance guys, the three fighter wings and the guys from Da Nang all got together. We had a big party. But we did business. We talked about tactics.”

For one meeting, they gathered in Bangkok.

“That was a helluva party,” he said. “They had elephants all the way down from Chiang Mai.”

Olds believed that having elephants there was Col. Howard C. “Scrappy” Johnson’s idea. He recalled sitting on an elephant and parading around the base.

“That was fun,” he said.

But he gruffly defended the rumors that tactics weren’t discussed much at these gatherings.

“We got a lot done,” he said. “I can’t give you a number of the losses weekly or monthly there in the summer of ’66. They were horrendous. From February or March of ’67 until I left, I only lost four people in Vietnam. They had been losing two or three a week until I got there. So, those meetings were very valuable.”

Olds explained that the name ‘Red River Valley” came from a geographic boundary. He recalls that the name was decided upon at a gathering held at his base.

“Scrappy Johnson was a deputy for operations for the wing at Takhli,” he said. “I told him, ‘We should organize these pilots. We’re all getting to know and like each other.’ Some youngster—to this day, I don’t know who—came up with the name ‘The Red River Valley Fighter Pilots Association.’ We became known as ‘River Rats.’ It stuck.”

Olds remembers that boundary well.

“Laos is long and skinny, and then the Vietnams,” he said. “We flew out of Thailand, to the east of Laos. We’d go northwest to pick up the tankers. They returned north and we refueled over Laos. And then we hit North Vietnam. The Vietnams went down on the outside of Laos.”

He follows an imaginary map to point to the first river.

“Coming in this way, the first river was the Black River,” he said. “It ran across here this way. You cross the mountains from the Black River to the Red River Valley. That river ran the same direction down to the China Sea. Hanoi sat on that river and Haiphong. Northeast of that river was a chain of mountains about 120 miles long. The highest were about 5,000 feet above sea level. That doesn’t sound like much, but consider that the bottoms were just about sea level. It was very rugged terrain. You crossed those two rivers. The qualification for being a River Rat was to have flown north of the Red River on missions.”

Olds said that the organization later was “administratively defined.”

“We didn’t give a damn,” he said. “We invited anybody who flew across there and later on, in Linebacker missions when they finally turned the B-52s loose, to join. They came to a couple of meetings. Bomber pilots are bomber pilots. They don’t show up anymore.”

Olds always looked forward to the yearly meetings.

“We’ve been lots of places—Dallas, Las Vegas, anywhere anybody foolishly volunteers to host one,” he said.

Post-Southeast Asia

After relinquishing command of the 8th TFW on Sept. 23, 1967, Olds reported for duty to the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., in December 1967. He served as commandant of cadets.

“My original ‘go home’ orders were Systems Command, which would have to do with production of new fighters or something,” he said. “But J.P. McConnell, the chief of staff of the Air Force, who had visited me several times, said, ‘I want him to be the commandant of cadets at the Air Force Academy.’ That job calls for a brigadier general; that was to the consternation of some other generals who had said that I would never be a general. So I got to be a general. I didn’t really care.”

Olds was promoted to brigadier general on June 1, 1968. He served as the academy’s commandant of cadets through January 1971.

“At the time, I was disappointed in my assignment to the academy,” he said. “I had knowledge of the war and of the lack of proper training here in the States. I thought I could share that knowledge to pilots being sent over. Nowadays, I realize that I did have a great influence on the cadets of that era. They still talk about Robin Olds. Of course, “his tales are wild,” but they still remember me. Not that I ever tried to impress them; I just got along with them. Oh, I had a lot of fun with those kids. Whew.”

Brig. Gen Olds’ last assignment would be director of aerospace safety in the Air Force Inspection and Safety Center at Norton Air Force Base, Calif. He stepped into that position in February 1971.

Olds oversaw the creation of policies, standards and procedures for Air Force accident prevention programs and dealt with work safety education, workplace accident investigation and analysis and safety inspections. He went on an inspection tour of U.S. air bases in Thailand in 1972. Operation Linebacker had commenced, and this was the first time American fighter jets had returned to Vietnam in four years. Olds retuned with a disturbing observation, stating Air Force pilots “couldn’t fight their way out of a wet paper bag.”

He wanted desperately to help, even offering to take a demotion to colonel to go back in the operational command and make things right. His request fell on deaf ears.

He retired from the Air Force on June 1, 1973. His military decorations and awards included the Air Force Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star with three oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with five oak leaf clusters, Air Medal with 39 oak leaf clusters, Air Force Commendation Medal, British Distinguished Flying Cross, French Croix de Guerre, Vietnam Air Force Distinguished Service Order, Vietnam Air Gallantry Medal with Gold Wings, Vietnam Air Service Medal and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal.

Post-retirement

Olds led an active life after retirement, traveling and speaking to groups.

“I had already bought a house in Steamboat Springs, Colo.,” he said. “I retired in California, drove directly here and have been here ever since. I used to ski almost every day, in the wintertime, golf in the summer, travel, trout fish, backpack. ‘Course, I’m reaching an age now where those things aren’t all that easy to do or can’t be done. But that’s all right.”

On July 21, 2001, Olds’ military contributions were acknowledged when he was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame, along with test pilot Col. Joseph H. Engle, Marine Corps ace Maj. Gen. Marion E. Carl and Albert Lee Ueltschi. He became the only person enshrined in both the National Aviation Hall of Fame and the College Football Hall of Fame.

Recently, Airport Journals asked Olds how he would sum up his journey through the military.

“My book was much too short,” he said. “I had so much to give and so little opportunity to do so. I’m still giving now, to those who care to listen.”

On June 14, 2007, Brig. Gen. Robin Olds passed away in his Steamboat Springs home, from congestive heart failure. Family and friends surrounded him. With the passing of this great man, it’s comforting to know the thoughts he recently expressed about his life.

“Just let it be said, ‘I lived happily ever after,'” concluded Olds.