|

By Di Freeze

The Roscoe Turner Flying Circus arrived in Lexington, Ky., in June 1925. As the highlight of a local celebration, an airship was to “fall in flames” for one mile over the University of Kentucky stadium. During festivities on June 4, J.W. “Bugs” Fisher, a daredevil who had recently begun performing with Roscoe Turner, received an “unexpected thrill.” According to the Lexington Herald, Roscoe Turner, piloting the aircraft, and Fisher had just returned to the Halley flying field from a flight. While Turner prepared to take a spin with Robert Radell, another pilot with the circus, Fisher hid in the undercarriage of the plane. “Not knowing that Fisher was hidden in the landing apparatus, Radell started the plane,” the newspaper reported. “When just in the act of leaving the ground, the ship struck a fence at one side of the lot, owing to the weight of the third occupant. The impact projected Fisher through the wing. ‘I am here, Roscoe,’ said the stowaway, in a cool and collected voice.” Although Fisher was uninjured, the plane sustained enough damage to cause the pilots to abandon the flight. Roscoe Turner colorfully represents the Golden Age of Aviation. One reporter summed up the flamboyant flier as having “an unending flow of blushless swank.” In the forward for Carroll V. Glines’ book, “Roscoe Turner, Aviation’s Master Showman,” Jimmy Doolittle described Turner, a friend and rival, as a “little ostentatious,” but also said he had great respect for his flying ability. Turner’s appearance, including his immaculately waxed mustache, was a great contrast to other racers of the time. He believed that if you looked like “a tramp or a grease monkey,” people wouldn’t have confidence in you. He always wore a stunning costume or uniform. “A uniform commands respect,” Turner said. “Aviation needs it.” He was also fond of saying that “aviation needs some glamour.” |

The early years

Roscoe Turner was born on Sept. 29, 1895, near Corinth, Miss. Although the family occupation was working the land, Turner decided that “looking at the rumps of two mules all day” wasn’t for him. He would’ve been content to become a locomotive engineer, but his father discouraged that dream, because the career was “too dangerous.”

Roscoe Turner started Roscoe Turner Flying Service with this Sikorsky S-29-A, a Waco 9, a Standard J-1 and a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny.

Shortly after completing 10th grade, Turner moved to Memphis, where he worked as an automotive mechanic. Later, after meeting some military aviators and hearing their stories, he decided he wanted to learn to fly. He tried to get into the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, but was turned down because he lacked the required education. He served as an ambulance driver until the Balloon Section accepted him as a flying cadet in January 1918. After being designated a free balloon pilot, he was put on flying status and commissioned a second lieutenant in the Aviation Section, Signal Corps Reserve, but the armistice was signed before he saw action.

In September 1919, Turner, by then a first lieutenant, was discharged from the military. Later, when the National Aeronautic Association issued pilot licenses, he was brevetted as a spherical balloon pilot.

Roscoe Turner joins the circus

In late 1919, Turner began flying the “Runser & Turner Cloudland Express” with Lt. Harry J. Runser. The aircraft, painted red and white, was a two-seater JN-4 Canuck, a Canadian modification of the Curtiss JN-3 “Jenny.” Runser handled most of the piloting duties, while Turner kept the plane mechanically sound and did most of the wing-walking and parachute jumping.

The men initially flew wearing their Army officers’ uniforms, but when the uniforms began to wear out, they hired the Brooks Uniform Company to make new ones. In magazine ads, Brooks soon began proclaiming, “You’ll like the new type uniform being universally adopted by pilots throughout the country.”

During 1920 and 1921, the duo barnstormed throughout the southern states. Although many people waited anxiously for the pilots to arrive in their town, not all were happy with the barnstormers. One person wrote to a local newspaper warning others that the “Sabbath desecration of Sunday fliers did more harm than the saloon ever had done.”

The men continued to please crowds until they landed in trouble after purchasing a Jenny from a Marine sergeant. They assumed the aircraft was one of many surplus Jennies on the market after WWI, but, in fact, it was government property. Both men were sentenced to one-year prison terms, but were released on parole after a few months.

Back in Corinth

After returning to Corinth, Turner ran an automotive repair shop and demonstrated for the local Gray automobile dealership. In his spare time, he patched together a “combination” Jenny, which he often flew from a pasture on the Suratt farm near Turner’s Hill, his family home.

In October 1923, the local paper announced that Turner was establishing an “aero corporation” in Sheffield, Ala. The company would offer “general aeroplane services” including making and selling aerial photographs and maps, advertising, exhibition and passenger flying, sightseeing trips, flights for hire and instruction in aerial piloting and navigation. Turner would serve as vice president and general manager.

At the time, the Muscle Shoals area was enjoying a real estate boom because Henry Ford was rumored to be buying a nitrogen-producing plant in Sheffield, the heart of the district, about 70 miles from Corinth. The Muscle Shoals Air Corporation, which began with two aircraft and was incorporated for $5,000 (500 shares sold at $10 each), was reported as the only corporation of its kind in Alabama.

With funds obtained from S.H. Curlee, the owner of St. Louis-based Curlee Clothing Company, Turner purchased an OX Standard and a Renault-powered French Breguet, a converted bomber that could accommodate four passengers and a pilot. Turner would repay part of the loan, but Curlee, a millionaire and airplane buff, agreed to advertising in trade. Turner would also transport Curlee company sales representatives on their rounds.

Several companies would utilize Turner’s aircraft and expertise over the years. His sponsor/advertisers included Camel cigarettes, Stokely-Van Camp Company, the Schwitzer Corporation, the Heinz Company, Continental Baking Company (Wonder Bread), Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and Champion Spark Plugs.

Turner says I do

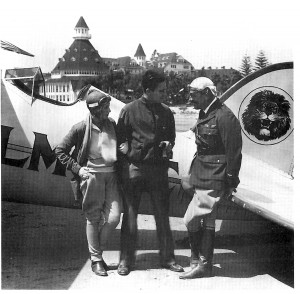

Roscoe Turner (right) visits with Ben Lyon and his wife, Bebe Daniels, after being engaged to pick them up at San Diego’s famed Coronado Hotel.

On Turner’s 29th birthday, he married Carline Hunter Stovall, an organist at the First Methodist Church. At the Suratt Farm, a small group watched as the couple said their vows from the cockpit of his Jenny, while a local minister performed the ceremony, standing on a wing.

The honeymooning couple took to the skies soon after. One of their stops was the Pulitzer Trophy Race in Dayton, Ohio, where media questioned the new bride.

“The motor makes so much noise it is almost impossible to quarrel while in the air,” the new Mrs. Turner told one reporter. “I may try making faces at my husband later, but I am afraid he will stunt the plane if I do.”

Several newspapers picked up the news that the groom and a Curlee employee had spent time in an Omaha jail for “bombing” the city with pamphlets announcing a baseball game being played there by Curlee employees.

“Omaha will get a ‘black eye’ for such treatment of visiting airmen!” one official stated, after several came to Turner’s defense. After they urged that the men be released, the matter was soon settled.

Flirting with fate

By December 1924, Arthur H. Starnes, the “Safety Last Boy,” had begun stunting with Turner. While reporting on Starnes’ death-defying stunts, one reporter stated, “Just what is to be gained by thus flirting with fate and giving hope to the undertaker is hard to understand.”

The Weekly Corinthian reported in January 1925 that Turner, “the flying man,” had made a trip to Pocahontas, Tenn., where he had a passenger “who has passed the three score and ten limit by a few years.”

“It is stated that Mr. DeVinney took the flight as a sort of challenge from a number of his friends,” the writer reported. “He had hardly got out of the machine before he said, ‘By smut! That is about the best ride I ever had. I might take another.'”

L to R: Lucien Prival, Wallace Beery, Carline Turner, Howard Hughes, Roscoe Turner, Greta Nissen and John Darrow mingle after Turner arrived at Burbank with the Sikorsky in 1928.

In April 1925, Turner completed plans for operating a school for “instruction in flying” at Gusmus Field, Ford City, Ala. This company would also offer commercial and sightseeing services. To celebrate, Turner hosted an “air frolic,” where he christened three new planes–“The Florence,” “The Sheffield” and “The Tuscumbia.”

The Roscoe Turner Flying Circus set up headquarters in the Sheffield Hotel. Both Turner’s companies flourished until Ford announced he wouldn’t be buying in the area, and the real estate boom began to wane.

When Starnes left to join another circus, “Bugs” Fisher entered the picture. On July 3, the Sheffield Standard reported that Turner and Fisher planned to perform their popular “Dive of Death” act at a Fourth of July celebration to be held at Philand Park, on Lake Wilson.

“New interest was attracted yesterday by the application of several local people who want to win the $100 offered by J.P. Anderson to any citizen who will duplicate the jump from the airplane into the lake,” the article said. “One person will be chosen from the applicants to make the jump. One of the provisions of Mr. Anderson’s offer is that no liability attaches to him for accidents or death occasioned by the attempt.”

Fisher injured his ankle a day before he was to perform his daring feat and ended up in the hospital. With trepidation, Turner agreed to allow 41-year-old Edward Etheridge to try to mimic the jump Fisher had already pulled off successfully at other locations. Reportedly, Etheridge had experience in making high dives from the mast of a schooner but not from an airplane.

Sober headlines on July 7, 1925, told of Etheridge’s death. Although the proposed jump was supposed to be at 48 feet, the exact height when Etheridge attempted his jump is unclear. Reports of Turner’s altitude ranged from 50 to 150 feet. Unconscious when rescued from the lake, Etheridge was rushed to the same hospital in Sheffield where Fisher was recuperating. He died a few hours later. An editorial later noted, “The Fourth of July proved most serious to stunt fliers; the morbid crowds went home satisfied.”

Roscoe Turner Airways and Hollywood

Roscoe Turner (right) gave flying instructions to some Hollywood actors, but good friend Wallace Beery was already a pilot.

In 1925, Turner formed Roscoe Turner Airways. In the spring of 1926, he began trying to establish passenger service out of Candler Field in Atlanta. He contacted financiers and merchants in that city and in New York and persuaded them to form a three-corporation alliance to pioneer north-south air service.

Roscoe Turner Airways’ partners were General Airways System and Sikorsky Aero Engineering. Turner planned to eventually have daily passenger and cargo service between Atlanta and New York utilizing four of Sikorsky’s new tri-motors, which were then still on the drawing board. When plans didn’t materialize, the Turners moved to Richmond, Va., in early 1927, after a group of executives invited Turner to establish an airport in Sandston, Va.

Richmond Air Junction soon offered two runways and a building that included sleeping quarters for visiting aviators. Turner started Roscoe Turner Flying Service at the field that February, with a Sikorsky S-29-A, a Waco 9, a Standard J-1 and a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny.

In addition to offering flying instruction, air taxi service and aerial photography, Turner also became a Waco dealer. In the summer of 1927, he obtained a $10,000 contract with United Cigar Stores Company to convert the S-29-A into a “Flying Cigar Store” for a 10-week tour of 37 cities along the East Coast.

Turner never forgave Hughes for a variety of issues raised during filming of “Hell’s Angels.” The S-29-A suffered a sad demise while masquerading as a rare German Gotha in the Howard Hughes’ motion picture, “Hell’s Angels.” At Van Nuys Airport, a large plot of ground was leased and cleared to recreate a WWI American airfield in France. Another field was acquired near Chatsworth, where a reproduction of the airdrome was built, and smaller fields were leased at Inglewood, Encino, Santa Cruz and San Diego.

One scene dictated that the S-29-A, one of hundreds of aircraft used, spin out of control to a fiery crash. Turner refused to spin the plane, but his contract allowed another pilot to perform the stunt. While that pilot was at the controls, he completely lost control of the plane. The pilot successfully bailed out, but a mechanic trapped on board died when the plane plummeted into an orange grove north of Los Angeles. That was one of four deaths to occur during filming.

Turner participated as a stunt pilot in other Hollywood films, including “Dawn Patrol.” Tragedy also struck during the shooting of that film. On Jan. 2, 1930, a mid-air collision took the lives of 10 people, including Kenneth Hawks, the brother of director Howard Hawks and acting director for the day.

Col. Roscoe Turner also made un-credited appearances in a few movies before appearing as himself in “Flight at Midnight,” released in 1939. While living in Hollywood, Turner further spruced up his appearance by donning new apparel created for him by the Cincinnati Regalia Company. His new uniform included a powder blue tunic, Pershing cap and a Sam Brown belt. He also had a jeweler design a pair of wings studded with 30 diamonds, bracketed with the initial “T” and a superimposed, intertwined “R,” worth an estimated four to five thousand dollars. While in the air, he wore a gold and crimson helmet; on the ground, he sported a blue officer’s cap.

To supplement his inconsistent income, Turner gave flying lessons to Hollywood stars and sightseeing flights to others, including Fred MacMurray and Clark Gable. He also became friends with Wallace Beery, who was already an accomplished pilot.

Nevada Airlines

In the spring of 1929, several executives from the Los Angeles area, including former Lockheed officials Ben S. Hunter and G. Ray Boggs, pooled their resources. On April 15, 1929, Nevada Airlines began tri-weekly service between Los Angeles, Reno and Las Vegas.

Four Lockheed Vegas were purchased to chauffeur rich clientele between Hollywood and Vegas. The route was dubbed “the line to freedom,” “the matrimonial special,” or “the liberty special,” depending on the purpose of the trip. Turner was hired as chief pilot and operations manager. Other cities were added, but after flourishing briefly, the airline discontinued services in February 1930.

During that period, Turner became acquainted with Nevada Governor Fred R. Balzar, who became an aviation enthusiast and made many trips with Turner during his term in office. In August 1929, he appointed Turner as an aide-de-camp on his personal staff, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Not to be outdone, California Governor James Rolph Jr. also appointed Turner to his staff, as colonel, in August 1931. After Balzar left office, Turner was reappointed by his successor, Governor Griswold.

Turner takes on air racing

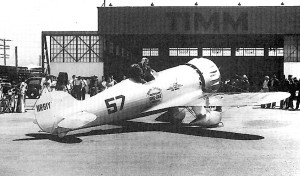

After Roscoe Turner crashed his Wedell-Williams Model 44, the aircraft was rebuilt for the 1937 Bendix race.

The National Air Races and Aeronautical Exposition was held in Cleveland in 1929. One of the features would be a nonstop cross-country derby from Los Angeles to Cleveland. Later known as the Bendix Trophy Race, it would become one of the popular event’s two prestige races.

Turner entered the air races that year for the first time. A month earlier, using one of the Vegas, he made a cross-country flight from Metropolitan Airport to Roosevelt Field. Harold Gatty, Capt. Fred Trosper and D.K. Lane had accompanied him. The flight to Roosevelt Field, made on August 21, took 19 hours and 35 minutes; the return trip was made in 23 hours and 59 minutes. Although it didn’t officially break any records, it was the first time a plane carrying passengers, in addition to pilot and mechanic, had crossed the U.S. in less than 24 hours each way.

Although impressed with the Vega, Turner had his eye on a later Lockheed model, an Air Express, for the 1929 Cleveland Air Races. He convinced Earl Bell Gilmore, president of California-based Gilmore Oil Company, to buy the plane he wanted from the General Tire & Rubber Company. The tire company had planned on entering it in the National Air Races that year, but was having trouble finding a competent pilot to fly the aircraft. Other companies were already sponsoring several of the most popular racers. Jimmy Mattern flew for Pure Oil, Frank Hawks for Texaco, and Jimmy Doolittle for Shell Oil.

The aircraft was painted cream with red and gold trim, and sported the company’s trademark lion’s head, to reflect Gilmore Oil’s popular Red Lion petroleum products. The aircraft would be available for Turner’s record-setting attempts, and serve as a “flying test bed” for the company’s lubricating oils, fuels and safety devices. Christened the “Gilmore Lion” by starlet Carlotta Miles at Los Angeles Metropolitan Airport before 5,000 people, the aircraft soon became a familiar sight at airports and public events throughout the west.

At Turner’s prompting, a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine replaced the aircraft’s experimental Hornet engine. Other modifications included additional fuel tanks.

On Oct. 31, 1929, Turner and four passengers departed Los Angeles in the Air Express for the nonstop race to Cleveland. Two Lockheed Vegas arrived ahead of him to earn first and second places. Spanning the distance in 13 hours, 15 minutes and 7 seconds, Henry J. Brown received the first-place purse of $5,000. The second-place prize of $2,000 went to Lee Schoenhair, for his time of 13 hours, 51 minutes and 10.8 seconds.

Turner was the third entrant to arrive. He had been delayed due to the need to circumnavigate severe late afternoon thunderstorms over Missouri. However, he was disqualified from receiving any prize money because he had arrived 90 minutes after the 6 p.m. deadline.

His hopes then turned to winning one of the closed-course races for open-cockpit aircraft powered with engines of not more than 800 cubic inches piston displacement. In that race over a 150-mile course, K.W. Cantwell, flying a Wasp-powered Vega, won with an average speed of 152.7 mph, earning a $675 prize. Turner, with a speed of 150.15 mph, came in second, which earned him $375.

Turner also entered the Thompson Cup, one of the featured events that year. Sponsored by Thompson Products Company, it was a 50-mile race around five pylons. Turner, flying his Wasp-powered Vega, competing against others flying civilian aircraft as well as against Army Air Corps and Navy pilots flying the latest fighters.

Doug Davis, a barnstormer and airline pilot, shocked participants and spectators by winning with a speed of 194.9 mph, in a commercially-made travel Air Model K “Mystery Ship.” He pocketed $750. Up to that point, military pilots had dominated the races in high-speed pursuit models. Second place ($450) went to Army Lt. R.G. Breene, flying a Curtiss P-3A pursuit ship, at 186.84 mph. Turner placed third ($300) with a speed of 163.44 mph.

The publicity surrounding the races encouraged Charles E. Thompson, president of Thompson Products, to sponsor a similar event beginning in 1930. He would present the Thompson Trophy “to offer inspiration and initiative to the development of aeronautics in general, and faster land planes immediately adaptable to commercial and military use in particular.”

The closed-course race would earn the winner a $5,000 purse. Open to civilian and military aircraft, the race would have no limitations on fuels, superchargers or numbers or types of engines. The first race for the Thompson Trophy was held in September 1930 as part of the National Air Race program at Curtiss-Reynolds Airport near Chicago.

Flying with Gilmore

Turner made his first flight with Gilmore, his pet lion, in April 1930. He would fly more than 25,000 miles with his unique companion. Louis Goebel presented the 3-week-old cub to Turner in a public ceremony after the aviator persuaded the owner of the Goebel Lion Farm to donate the cub, born in February 1930, to him.

Gilmore was initially nervous about flying but soon grew to love it. He accompanied his flashy owner on many of his cross-country record-breaking flights. To satisfy the Humane Society, Turner outfitted the lion with a parachute created by the Irvin Parachute Co.

The dashing ladies man often told people he preferred Gilmore’s company, since he was safer and seldom got him in trouble. Turner took Gilmore with him golfing and, when out of town, to leading hotels, where the pair registered as “Roscoe Turner and Gilmore.” Hotel managers delighted in the publicity, and often asked that Gilmore leave his paw print in the guest register.

At airports, Turner would always have someone ready a cage for Gilmore so the children could see him. When Gilmore passed 150 pounds, however, his weight became a problem in the aircraft, and he ceased to be Turner’s flying companion.

The Turners initially received a permit to keep Gilmore in the garage of their Beverly Hills home. However, after the lion leaped on top of their touring car and smashed the cloth top, they built him a $2,500 house on a 30-square-foot fenced arena in their backyard. Gilmore was often allowed in the Turners’ home, but he spent hours watching fish in his very own fishpond and gnawing the branches on his rubber tree. When he got bored with that, he could swat the automobile tire hanging from its branches.

A portable cage was built to transport Gilmore to and from various motion picture theaters, where it was parked in front to draw a crowd. The lion was also put on display at the United Air Terminal in Burbank.

Gilmore was later displayed in a cage beside a Gilmore service station in Beverly Hills, on the corner of the Earl Gilmore estate at Fairfax and Beverly Boulevard. But in 1935, after a Warner Brothers executive living near the station wrote to the Los Angeles chief of police, saying the lion roared through the night and declaring him a public nuisance, Gilmore was moved to a nearby garage.

In June 1935, Gilmore was moved to Burbank Airport, where Turner’s mechanic, Don Young, looked after him. With Gilmore no longer his flying companion, to continue the lion theme, Turner wore a lion’s skin coat and gloves resembling lion’s paws, and carried a lion’s tail swagger stick.

Flying into history

On May 27, 1930, Turner broke the previous east-west record by flying between Roosevelt Field and Grand Central Airport in Los Angeles in 18 hours, 42 minutes and 54 seconds. On July 16, he left Vancouver, B.C., and, after crossing three nations, landed in Agua Caliente, Mexico, nine hours, 14 minutes and 30 seconds later, setting another record.

In 1932, Turner made the trip between Mexico City and Los Angeles, while carrying passengers, in 11 hours and 30 minutes. On November 12, he set a transcontinental record of 12 hours and 35 minutes, flying from New York to Burbank. That same year, he placed third in the Bendix Race, the Thompson Trophy Race, and the Shell Speed Dash at the National Air Races in Cleveland, while flying a Wedell-Williams Model 44 racer.

In 1933, while at the National Air Races in Los Angeles, Turner, again flying the Wedell-Williams, placed first in the Bendix Race and in the Shell Speed Dash. He was declared the winner of the Thompson Trophy, but was disqualified when officials discovered he had cut a pylon and not circled it on the required lap.

On Sept. 25, 1933, flying the Wedell-Williams, Turner set a transcontinental record–10 hours, four minutes and 30 seconds–from Los Angeles to New York. His achievements were rewarded by the presentation of the Harmon Trophy in New York City by the American chapter of the Ligue Internationale des Aviateurs.

In 1934, Turner eclipsed his own record, flying from Burbank to New York in 10 hours, 2 minutes and 39 seconds. That same year, at the National Air Races in Cleveland, he won the Thompson Trophy and placed second in the Shell Speed Dash.

After borrowing a P&W-powered Boeing 247D airliner owned by United Airlines, Turner entered the MacRobertson International Air Race from London to Melbourne, Australia. The race began on Oct. 20, 1934, and had both a speed and handicap category. Out of more than 60 entries, only 20 aircraft were ready on race day. Turner flew with Clyde E. “Upside Down” Pangborn and Reeder Nichols. The Boeing flew over the finish line after 92 hours, 22 minutes and 38 seconds. Turner’s crew pocketed the second-place prize of $7,500 in the speed category.

In 1935, flying a Wedell-Williams powered by a 1,000-hp Hornet, he placed second in the Bendix cross-country race during the National Air Races in Cleveland, losing the race by a mere 23.5 seconds. That same year, ground was broken for Roscoe Turner Airport, built on the Suratt pasture in Corinth, Alcorn County. Former Congressman Zeke Candler presented Turner with the key to the city at a dedication ceremony on Oct. 15, 1936.

The Turner Special

In 1936, prior to the races again being held in Cleveland, Turner discussed his designs for a new racer with University of Minnesota Professor Howard W. Barlow, who had previously helped him with a more powerful redesign of the Wedell-Williams. Turner contracted with Lawrence W. Brown Aircraft Company of Los Angeles to build the aircraft. Unhappy with the end result, however, he had the airplane disassembled and shipped to the Laird factory at Chicago. The aircraft was redesigned, including lengthening the fuselage and significant changes to the wing, which had been too narrow. The mid-wing monoplane, now weighing about 400 unwanted pounds less, incorporated all of the latest aerodynamic advances.

Although he was happy with the design, Turner wasn’t happy that Laird registered the racer as the Laird-Turner Racer. He had intended it to be the Turner Special.

Due to time spent redesigning the aircraft, Turner missed the 1936 racing season. He took off for Burbank in his new racer on Aug. 30, 1937. Near Albuquerque, the engine began to run rough and Turner had to land. After some repairs, he again took off, on Sept. 2, but further mechanical problems forced him to miss the Bendix.

After bad luck that included flying through a hailstorm, Turner finally arrived at Cleveland on Sept. 5. Additional repairs were needed, but that didn’t prevent him from entering the Thompson Trophy Race. Bearing race number 29, the racer, powered by a 14-cylinder P&W Twin Wasp radial engine and sponsored by Ring Free Oil, entered the 1937 race carrying the name “Ring Free Meteor.”

It looked like Turner was going to win the race when Steve Wittman, in the lead in his D-12 “Bonzo,” developed trouble on the 17th lap. Turner passed him and held the lead until the final lap, but the sun blinded him on one of the final pylons. Believing he had cut the pylon, he returned to re-circle it. At that point, Earl Ortman in the Keith Rider R-3 and Rudy Kling in the Folkerts SK-3 passed him. Turner finished third, with a speed of 253.802 mph.

The following year, President Roosevelt signed the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, which included the establishment of the Civil Aeronautics Authority. Turner, who resented government interference in the business of aviation and had bluntly expressed his opinions on many occasions, foresaw the changes soon to occur. In the 1938 Bendix Race, all pilots were required to possess instrument ratings and have radio equipment installed in their aircraft. Other changes occurred within the racing industry, such as a rule that no plane entering the Bendix could also compete for the Thompson.

In the 1938 National Air Races, Turner’s new sponsor was the Pump Engineering Service Corporation of Cleveland. “Pesco Special” replaced the words “Ring Free” on his racer.

Believing he could win both races, Turner was disappointed that he couldn’t compete in both the Bendix and the Thompson. His crew chief, Don Young, had made various modifications that upped the aircraft’s top speed by about 25 mph.

Turner opted for the Thompson. He won with an average speed of 283.416 mph, becoming the first person to capture the trophy more than once. Turner greatly appreciated the $22,000 prize money, because as usual, he had creditors he needed to pay.

He also received the Cliff Henderson Award, based on racing points, making him “America’s number 1 speed flier for 1938,” and the Harmon Trophy for being America’s premier aviator.

Turner was back in the same racer in 1939, this time sponsored by Champion Spark Plugs. “Miss Champion” won the Thompson Trophy with a speed of 282.5 mph, making Turner the only three-time winner of the Thompson Trophy Race and earning him $16,000. He also set a new record for a closed course during the qualifying race, at 299.003 mph–the fastest lap yet flown over a 10-mile course–and was again awarded the Henderson Award.

After taxiing to the winner’s line in front of the grandstand, Turner shocked and disappointed the crowd by shouting, “Make way for the photographers! This is the last chance you boys will have to photograph me with the Thompson Trophy. I’m not going to race anymore.”

He later confirmed the statement, saying he’d be 44 years old that month and that racing was a “young man’s game.” That same year, he again received the Harmon Trophy.

Roscoe Turner Aeronautical Corporation

Turner couldn’t have continued racing even if he had wanted to, at least for a few years. Due to World War II, the races weren’t resumed until 1946. By then, it was indeed a different game. Many pilots who took to the skies to race at that time did so in highly sophisticated, surplus WWII Army and Navy fighters.

The Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce and City Council helped Turner decide what his next venture would be when they revealed their intention to develop a major airport. Turner presented a formal proposal to the city to build a hangar and administration building on 52 acres of leased land, on which he planned to open a fixed base operation. However, the lease and commercial property privileges he sought conflicted with the existing lease of the Central Aeronautical Corporation, then offering aircraft sales and services there.

Turner, with Ray P. Johnson and William M. Joy, bought all CAC stock, including assets and liabilities, for $20,000, in November 1939. On Feb. 8, 1940, the charter was amended, changing the name to the Roscoe Turner Aeronautical Corporation.

The RTAC building and an adjoining heated hangar were dedicated in May 1941. The FBO at Weir Cook Airport (now Indianapolis International Airport) offered flight instruction, a service and repair shop, and hangar space for 40 small planes and chartered services, including ambulance and aerial survey. Soon, Roscoe Turner Aviation Institute offered a supplement of complete ground school courses.

In the mid-1940s, Turner became a distributor for his longtime friends, Walter and Olive Ann Beech. One of their outstanding distributors, Turner would become the first enshrinee in Beechcraft’s Hall of Fame. RTAC also became a sales and service facility for Waco, Stinson and Taylorcraft planes.

As a reminder of his glorious racing career, Turner’s racer was hung from the rafters. The pilot who had become known for being vocal with his opinions about what was happening in the world–sometimes through speeches he made on the radio, and, for a period of several months, through a weekly syndicated column–now advocated a separate Air Force, independent of the Army. Stating that the cheapest military aircraft cost about $35,000, he envisioned a “mosquito air force” or “flivver-plane army” of 200,000 light planes for defense, capable of carrying 100-lb. bombs.

“You can get these little ships in bunches like bananas, for $2,000 apiece,” he said. “Send them out in droves and you can blow any invading army to pieces before it gets a start.”

The target of many of his speeches was America’s youth. He warned, “Hitler will whip the world, including the U.S., unless aviation is put entirely in the hands of aviation people.”

Turner had tried unsuccessfully to enter his school in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, established by the Civil Aeronautics Authority in 1939. Eventually, the National Aviation Training Association (later the National Aviation Trades Association) was formed to represent the interests of flight school operators. Turner became an active member and later its president.

By that time, Turner had separated from his wife. He was anxious to get back into a uniform, preferably as a commissioned officer. He wrote letters to Gen. Claire L. Chennault, commander of the Flying Tigers in China, and to Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the second highest-ranking Army Air Forces officer, volunteering to ferry B-17s to the war zones. He even offered his services to the Royal Australian Air Force. When he was politely turned down, he wrote to Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, chief of staff of the Army Air Forces, and asked for renewal of his commission in the National Guard. Arnold replied that he couldn’t make such an appointment because the National Guard was under state jurisdiction.

Turner exchanged several letters with Gen. James H. Doolittle in early 1942. Like the others, Doolittle responded that Turner’s present job of running a training school was far more important to the war effort than having him assigned to Doolittle’s staff.

In January, after Doolittle had been assigned to General Arnold’s staff in Washington, Turner wrote, “If this thing gets too tough, I think it would be a good idea for you and I to leave the country and go over there and organize our own fighting squadron.” Turner wanted to organize a 50-plane group of B-17s with “no pilot under 40 years of age.” He also envisioned using graduates from his school as copilots, and establishing a volunteer gunners’ crew.

“I’ll bet we would be the meanest outfit that ever hit the air,” he said.

Unbeknownst to Turner, Doolittle was already planning and organizing a raid on Japan. After Doolittle’s surprise attack on Tokyo and four other Japanese cities on April 18, 1942, and his promotion to brigadier general, Turner immediately wired him in Washington.

“Congratulations, you dog!” he said. “Why didn’t you take me with you? I could have been your copilot. Guess you have shown the world we old boys can still be of service as combat pilots.”

In February 1943, the War Training Service contracted with Turner’s company to conduct a cross-country course for 30 students. The RTAC fleet now included a Stinson Tri-motor, two Wacos, three Taylorcrafts, two Piper Cub Cruisers, one Fleetwing and a Link trainer.

The War Training Service began winding down in late 1943, and RTAC’s program was discontinued in mid-January 1944. By June 30, the Army had sent its last classes to the civilian contractor schools; the Navy graduated its last class in August. The training program was discontinued in mid-1944. In all, 1,132 educational institutions had been involved and 1,460 contractors had qualified 435,165 trainees, including several hundred women. RTAC turned out an estimated 3,500 students during its participation in the CPT/War Training Service programs.

Turner Airlines

On Dec. 13, 1946, the recently-divorced Turner married Madonna M. Miller. Madonna Turner, formerly from Sheridan, Ind., became president of RTAC in 1950. That same year, the couple moved to a home on a four-acre estate in Indianapolis.

Previously, RTAC had started and was later forced to discontinue daily charter service between Detroit and Memphis. As soon as operations began, in July 1944, Chicago & Southern Airlines filed a formal protest with the Civil Aeronautics Board, alleging the operation of a daily scheduled service was in direct violation of federal regulations.

No special approval was needed from the CAB to operate a charter service. However, to run a regular airline over a set route on pre-announced schedules, hearings had to be held, a financial fitness investigation made and approval given by the CAB. When ordered to discontinue service immediately or take appropriate steps to place the operations within the terms of the board’s definition of “non-scheduled service,” Turner terminated the service after only 40 days of operation. They had carried 100 revenue passengers.

In February 1948, RTAC was granted authority to serve 14 cities in Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan and Ohio. Turner Airlines was formed in August 1949, and service was inaugurated between Indianapolis and Grand Rapids that November. The airline was based at the RTAC hangars.

Due to a lack of investors, Turner was forced to sell the franchise to John and Paul Weesner. In November 1950, after experiencing financial difficulties, the Weesners sold their interest in Turner Airlines, and it became Lake Central Airlines. Allegheny Airlines, which later absorbed the airline, eventually became USAir.

Air power

Turner continued to give speeches, his main purpose to “pound into the American people the vital importance of air power.” He admonished the American people “not to let the nation’s defenses languish.”

“If the American people had listened to Billy Mitchell after World War I, there would never have been a second war,” he said. “And if the people don’t realize the value of a huge air force now, there will be a third world conflict, without a doubt.” He admonished that Americans had a choice to make: they could either “appropriate the money for a large, effective, hard-hitting air force” or “save the money and pay for another world war.”

Turner received the Distinguished Flying Cross in a Pentagon ceremony on Aug. 14, 1952, for “extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight.” Presented by Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Nathan F. Twining, it was the first time the award had been presented to a civilian in more than 20 years. It was one of only six awarded to a nonmilitary person up to that time. Four years later, Turner received the Paul Tissandier Diploma awarded by the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale.

Turner becomes a millionaire

On April 2, 1961, Turner attended a ceremony in Corinth dedicating a new Roscoe Turner Airport. The first one, built in 1936 on the Suratt farm, had been plowed up; the new one had been built in another location with a 5,000-foot lighted runway and landing aids.

Turner’s business also looked good. One day, in the early 1960s, Madonna Turner advised her husband that he was a millionaire. Although he reportedly laughed it off, certainly, he must’ve been happy. Many times in his life debt hung over his head. He wasn’t always the smartest businessman and he had a habit of spending more than he made.

Turner had acquired five automobiles and a boat by that time, and had built two garages to house them. He enjoyed working around the house, and in his kitchen decorating with a racing motif, contentedly broiled steaks and fried catfish, sometimes for large parties.

By the mid-1960s, Turner was again faced with financial difficulties. Knowing that, Harry Combs, a good friend, made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. In December 1966, the Gates Rubber Company had purchased Combs Aircraft, which became a subsidiary of Gates Aviation Corporation. Several months later, Combs suggested to Charles C. Gates that they give Turner a hand.

Although it put money in his pocket, the deal Turner made with Gates also put him in hot water with Olive Ann Beech, who had taken over Beechcraft after Walter’s death in 1950.

“I initially talked with Roscoe about it,” said Combs in an interview in 2001. “I made a deal with him, and then Hig Gould (the president of Gates Aviation at the time) went down there. He talked Roscoe into selling 51 percent of his business to Gates. It was purchased without the knowledge of Mrs. Beech. The minute she heard, Olive Ann got mad.

“Hig should have told her, ‘We think we can make a good distributorship for you.’ But he didn’t, and she cancelled out Roscoe. They just crucified him. Roscoe was very sick. I went to Charlie and said, ‘We can’t let this happen! We have to pay him the balance–buy his minority interest–even though it’s been cancelled.'”

Gates Rubber Company acquired the balance of RTAC in March 1967, shortly before acquiring majority interest (65 percent) of the Lear Jet Corporation, also in financial straits. The agreement called for Turner to remain as chairman of the board and his wife as president temporarily.

In 1975, Combs Aircraft, Roscoe Turner Aeronautical and Gates Aviation Palms Springs were officially consolidated under the name Combs Gates Inc. Thirteen years later, AMR Service Corporation, a sister company to American Airlines, purchased Combs Gates’ network of six FBOs. They were consolidated with existing AMR Service FBOs as AMR Combs the following year. In 1999, AMR Corp. sold AMR Combs, its executive aviation services unit, to Signature Flight Support, BBA Group’s service division. The division added the FBOs to their existing 42.

An icon passes on

In July 1968, the Indianapolis Airport Authority approved the construction of the Roscoe Turner Museum and Educational Center at Weir Cook Field. Turner began planning the move of his memorabilia.

A few months later, after being diagnosed with bone cancer, Turner was taken to the Ochsner Clinic, where he received cobalt treatments. While recuperating at his home in Florida, he gradually gained strength.

The Turners returned to oversee construction of the Weir Cook project in January 1969. Financed by the Roscoe Turner Aviation Foundation, the museum would house his famous racer and his faithful 1929 Packard Phaeton, which he had used extensively for hauling baggage, parts and people to and from racing ventures. Don Young, Turner’s faithful mechanic of many years, had recently restored the car to mint condition.

When the Turners moved to Indianapolis, Goebel’s African Lions in Camarillo, Calif., agreed to care for Gilmore. He was later moved to the Jungle Compound, in Thousand Oaks, Calif., where he died in 1952. A taxidermist preserved Gilmore, who weighed over 600 pounds at the time of his death. Gilmore graced Turner’s den until the museum opened and the lion took his place of honor there.

The museum also showcased flying memorabilia including Turner’s many trophies and awards. The Turners officiated at the groundbreaking at the corner of South High School Road and Roscoe Turner Drive during the last week of July 1969.

In May 1970, Turner was again hospitalized at the Ochsner Clinic, and his condition continued to deteriorate. In June, at his request, he was flown to Indianapolis in a Learjet. His health worsened steadily until his death on June 23, 1970, three months short of his 75th birthday.

The Roscoe Turner Museum and Educational Center was formally dedicated on Sept. 29, 1970. Five years later, in November 1975, Turner was posthumously enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame. General Doolittle presented the award to Madonna Turner.

Bob Hoover, a fellow NAHF enshrinee, has fond memories of time spent with Turner. Some of the most humorous memories involved Turner’s deafness in his later years.

“Since there were no hearing aids in those days, people had to speak quite loudly for him to hear them,” he said. “Believing he had to respond in kind, Roscoe would literally yell. This became something of a problem, especially when he took Colleen and me out to his country club for dinner.”

Hoover said they looked forward to visiting with him, but would cringe when Turner began to tell dirty jokes.

“With his loud voice, everybody in the room was exposed to his off-color stories,” he said. “We were embarrassed as could be, but if his jokes bothered nyone, they didn’t show it.”

He recalled Turner once asking him, “How many pilots have you known to have made a million dollars, lost it, and made it back?”

“I had to admit he was the only one I knew who could make that claim,” Hoover said.

In 1976, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum was dedicated in Washington, D.C. Madonna Turner transferred many of the items that had been housed at the short-lived Roscoe Turner Museum to the new museum, including the 1934 Thompson Trophy-winning Wedell-Williams.

Turner’s trophies were displayed in a large glass case in the center of the main entrance of the new museum. The Boeing 247D he flew in the London-Melbourne race was hung from the ceiling. His famed racer, the Turner RT-14 Meteor, was placed on display, with Gilmore standing under the wing.

The exhibit remained in place for several years before being transferred to the Smithsonian’s Paul E. Garber Facility in Suitland, Md. Presently, the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is home to the Turner RT-14 Meteor and Gilmore, and displays a case of Turner clothing and trophies.

Turner’s Phaeton is now included in the collection of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Photographs and correspondence are archived at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center.

Quotations in this article came from sources including Carroll V. Glines’ book, “Roscoe Turner, Aviation’s Master Showman,” as well as the “Corinth Information Data Base.”

- L to R: Lucien Prival, Wallace Beery, Carline Turner, Howard Hughes, Roscoe Turner, Greta Nissen and John Darrow mingle after Turner arrived at Burbank with the Sikorsky in 1928.

- Roscoe Turner poses with Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker (left), Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, at the 1934 Indianapolis 500 races.

- Roscoe Turner made his first flight with Gilmore, his pet lion, in 1930. As a cub, Gilmore went on many flights in the enclosed cabin of the Lockheed Air Express.

- After receiving complaints from the Humane Society, Roscoe Turner had the Irvin Parachute Co. make Gilmore a parachute.

- Roscoe Turner flew more than 25,000 miles with Gilmore. To carry out the lion theme on flights after Gilmore grew to 150 pounds and began staying home, Turner wore a lion’s skin coat and gloves like lion’s paws, and carried a lion’s tail swagger stick.

- Gilmore patiently poses for yet another picture with his owner, Roscoe Turner’s Wedell-Williams racer and the Lockheed Air Express (at Burbank, Calif.).

- Roscoe Turner with fellow racer Bennie Howard at the National Air Races in Cleveland in 1935.

- Roscoe Turner, holding the Thompson and Bendix trophies, poses with Charles E. Thompson (left) and Vincent Bendix.

- L to R: Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post, Roscoe Turner and Laura Ingalls, who met by chance at the Lockheed factory in 1935, look over Post’s Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine, which will be installed in the Winnie Mae.

- After Roscoe Turner crashed his Wedell-Williams Model 44, the aircraft was rebuilt for the 1937 Bendix race.

- Lawrence Brown began the original construction of the Turner Special (Meteor), designed to replace Roscoe Turner’s Wedell-Williams, which incorporated a straight-wing configuration. Matty Laird later modified the design.

- Roscoe Turner’s famed racer, the Turner RT-14 Meteor, is in The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dullas International Airport.

- Roscoe Turner prepares to squeeze into the small cockpit of the Ring Free Meteor.

- In the early 1940s, the Roscoe Turner Aeronautical Corporation was formed at Weir Cook Airport (now Indianapolis International Airport). The fixed base operation was a Beechcraft distributor and offered many other services.

- Roscoe and Madonna Turner relax in the den of their Indianapolis home with their pet bulldog and Gilmore, who was preserved by a taxidermist after his death in 1952.